Полная версия

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

‘Quite, Hammond, quite! But if someone starts making love to Julia, you begin to simmer; and if he goes on, you are soon at boiling point.’ … Julia was Hammond’s wife.

‘Why, exactly! So I should be if he began to urinate in a corner of my drawing-room. There’s a place for all these things.’

‘You mean you wouldn’t mind if he made love to Julia in some discreet alcove?’

Charlie May was slightly satirical, for he had flirted a very little with Julia, and Hammond had cut up very roughly.

‘Of course I should mind. Sex is a private thing between me and Julia; and of course I should mind anyone else trying to mix in.’

‘As a matter of fact,’ said the lean and freckled Tommy Dukes, who looked much more Irish than May, who was pale and rather fat: ‘As a matter of fact, Hammond, you have a strong property instinct, and a strong will to self-assertion, and you want success. Since I’ve been in the army definitely, I’ve got out of the way of the world, and now I see how inordinately strong the craving for self-assertion and success is in men. It is enormously overdeveloped. All our individuality has run that way. And of course men like you think you’ll get through better with a woman’s backing. That’s why you’re so jealous. That’s what sex is to you … a vital little dynamo between you and Julia, to bring success. If you began to be unsuccessful you’d begin to flirt, like Charlie, who isn’t successful. Married people like you and Julia have labels on you, like travellers’ trunks. Julia is labelled Mrs Arnold B. Hammond – just like a trunk on the railway that belongs to somebody. And you are labelled Arnold B. Hammond, C/O Mrs Arnold B. Hammond. Oh, you’re quite right, you’re quite right! The life of the mind needs a comfortable house and decent cooking. You’re quite right. It even needs posterity. But it all hinges on the instinct for success. That is the pivot on which all things turn.’

Hammond looked rather piqued. He was rather proud of the integrity of his mind, and of his not being a time-server. None the less, he did want success.

‘It’s quite true, you can’t live without cash,’ said May. ‘You’ve got to have a certain amount of it to be able to live and get along … even to be free to think you must have a certain amount of money, or your stomach stops you. But it seems to me you might leave the labels off sex. We’re free to talk to anybody; so why shouldn’t we be free to make love to any woman who inclines us that way?’

‘There speaks the lascivious Celt,’ said Clifford.

‘Lascivious! Well, why not –? I can’t see I do a woman any more harm by sleeping with her than by dancing with her … or even talking to her about the weather. It’s just an interchange of sensations instead of ideas, so why not?’

‘Be as promiscuous as the rabbits!’ said Hammond.

‘Why not? What’s wrong with rabbits? Are they any worse than a neurotic, revolutionary humanity, full of nervous hate?’

‘But we’re not rabbits, even so,’ said Hammond.

‘Precisely! I have my mind: I have certain calculations to make in certain astronomical matters that concern me almost more than life or death. Sometimes indigestion interferes with me. Hunger would interfere with me disastrously. In the same way starved sex interferes with me. What then?’

‘I should have thought sexual indigestion from surfeit would have interfered with you more seriously,’ said Hammond satirically.

‘Not it! I don’t over-eat myself and I don’t over-fuck myself. One has a choice about eating too much. But you would absolutely starve me.’

‘Not at all! You can marry.’

‘How do you know I can? It may not suit the process of my mind. Marriage might … and would … stultify my mental processes. I’m not properly pivoted that way … and so must I be chained in a kennel like a monk? All rot and funk, my boy. I must live and do my calculations. I need women sometimes. I refuse to make a mountain of it, and I refuse anybody’s moral condemnation or prohibition. I’d be ashamed to see a woman walking around with my name-label on her, address and railway station, like a wardrobe trunk.’

These two men had not forgiven each other about the Julia flirtation.

‘It’s an amusing idea, Charlie,’ said Dukes, ‘that sex is just another form of talk, where you act the words instead of saying them. I suppose it’s quite true. I suppose we might exchange as many sensations and emotions with women as we do ideas about the weather, and so on. Sex might be a sort of normal physical conversation between a man and a woman. You don’t talk to a woman unless you have ideas in common: that is you don’t talk with any interest. And in the same way, unless you had some emotion or sympathy in common with a woman you wouldn’t sleep with her. But if you had…’

‘If you have the proper sort of emotion or sympathy with a woman, you ought to sleep with her,’ said May. ‘It’s the only decent thing, to go to bed with her. Just as, when you are interested talking to someone, the only decent thing is to have the talk out. You don’t prudishly put your tongue between your teeth and bite it. You just say out your say. And the same the other way.’

‘No,’ said Hammond. ‘It’s wrong. You, for example, May, you squander half your force with women. You’ll never really do what you should do, with a fine mind such as yours. Too much of it goes the other way.’

‘Maybe it does … and too little of you goes that way, Hammond, my boy, married or not. You can keep the purity and integrity of your mind, but it’s going damned dry. Your pure mind is going as dry as fiddlesticks, from what I see of it. You’re simply talking it down.’

Tommy Dukes burst into a laugh.

‘Go it, you two minds!’ he said. ‘Look at me … I don’t do any high and pure mental work, nothing but jot down a few ideas. And yet I neither marry nor run after women. I think Charlie’s quite right; if he wants to run after the women, he’s quite free not to run too often. But I wouldn’t prohibit him from running. As for Hammond, he’s got a property instinct, so naturally the straight road and the narrow gate are right for him. You’ll see he’ll be an English Man of Letters before he’s done. A.B.C. from top to toe. Then there’s me. I’m nothing. Just a squib. And what about you, Clifford? Do you think sex is a dynamo to help a man on to success in the world?’

Clifford rarely talked much at these times. He never held forth; his ideas were really not vital enough for it, he was too confused and emotional. Now he blushed and looked uncomfortable.

‘Well!’ he said, ‘being myself hors de combat, I don’t see I’ve anything to say on the matter.’

‘Not at all,’ said Dukes; ‘the top of you’s by no means hors de combat. You’ve got the life of the mind sound and intact. So let us hear your ideas.’

‘Well,’ stammered Clifford, ‘even then I don’t suppose I have much idea … I suppose marry-and-have-done-with-it would pretty well stand for what I think. Though of course between a man and woman who care for one another, it is a great thing.’

‘What sort of great thing?’ said Tommy.

‘Oh … it perfects the intimacy,’ said Clifford, uneasy as a woman in such talk.

‘Well, Charlie and I believe that sex is a sort of communication like speech. Let any woman start a sex conversation with me, and it’s natural for me to go to bed with her to finish it, all in due season. Unfortunately no woman makes any particular start with me, so I go to bed by myself; and am none the worse for it … I hope so, anyway, for how should I know? Anyhow I’ve no starry calculations to be interfered with, and no immortal works to write. I’m merely a fellow skulking in the army…’

Silence fell. The four men smoked. And Connie sat there and put another stitch in her sewing … Yes, she sat there! She had to sit mum. She had to be quiet as a mouse, not to interfere with the immensely important speculations of these highly-mental gentlemen. But she had to be there. They didn’t get on so well without her; their ideas didn’t flow so freely. Clifford was much more hedgy and nervous, he got cold feet much quicker in Connie’s absence, and the talk didn’t run. Tommy Dukes came off best; he was a little inspired by her presence. Hammond she didn’t really like; he seemed so selfish in a mental way. And Charles May, though she liked something about him, seemed a little distasteful and messy, in spite of his stars.

How many evenings had Connie sat and listened to the manifestations of these four men! these, and one or two others. That they never seemed to get anywhere didn’t trouble her deeply. She liked to hear what they had to say, especially when Tommy was there. It was fun. Instead of men kissing you, and touching you with their bodies, they revealed their minds to you. It was great fun! But what cold minds!

And also it was a little irritating. She had more respect for Michaelis, on whose name they all poured such withering contempt, as a little mongrel arriviste, and uneducated bounder of the worst sort. Mongrel and bounder or not, he jumped to his own conclusions. He didn’t merely walk round them with millions of words, in the parade of the life of the mind.

Connie quite liked the life of the mind, and got a great thrill out of it. But she did think it overdid itself a little. She loved being there, amidst the tobacco smoke of those famous evenings of the cronies, as she called them privately to herself. She was infinitely amused, and proud too, that even their talking they could not do, without her silent presence. She had an immense respect for thought … and these men, at least, tried to think honestly. But somehow there was a cat, and it wouldn’t jump. They all alike talked at something, though what it was, for the life of her she couldn’t say. It was something that Mick didn’t clear, either.

But then Mick wasn’t trying to do anything, but just get through his life, and put as much across other people as they tried to put across him. He was really anti-social, which was what Clifford and his cronies had against him. Clifford and his cronies were not anti-social; they were more or less bent on saving mankind, or on instructing it, to say the least.

There was a gorgeous talk on Sunday evening, when the conversation drifted again to love.

‘Blest be the tie that binds Our hearts in kindred something-or-other’ – said Tommy Dukes. ‘I’d like to know what the tie is … The tie that binds us just now is mental friction on one another. And, apart from that, there’s damned little tie between us. We bust apart, and say spiteful things about one another, like all the other damned intellectuals in the world. Damned everybodies, as far as that goes, for they all do it. Else we bust apart, and cover up the spiteful things we feel against one another by saying false sugaries. It’s a curious thing that the mental life seems to flourish with its roots in spite, ineffable and fathomless spite. Always has been so! Look at Socrates, in Plato, and his bunch round him! The sheer spite of it all, just sheer joy in pulling somebody else to bits … Protagoras, or whoever it was! And Alcibiades, and all the other little disciple dogs joining in the fray! I must say it makes one prefer Buddha, quietly sitting under a bo-tree, or Jesus, telling his disciples little Sunday stories, peacefully, and without any mental fireworks. No, there’s something wrong with the mental life, radically. It’s rooted in spite and envy, envy and spite. Ye shall know the tree by its fruit.’

‘I don’t think we’re altogether so spiteful,’ protested Clifford.

‘My dear Clifford, think of the way we talk each other over, all of us. I’m rather worse than anybody else, myself. Because I infinitely prefer the spontaneous spite to the concocted sugaries; now they are poison; when I begin saying what a fine fellow Clifford is, etc., etc., then poor Clifford is to be pitied. For God’s sake, all of you, say spiteful things about me, then I shall know I mean something to you. Don’t say sugaries, or I’m done.’

‘Oh, but I do think we honestly like one another,’ said Hammond.

‘I tell you we must … we say such spiteful things to one another, about one another, behind our backs! I’m the worst.’

‘And I do think you confuse the mental life with the critical activity. I agree with you, Socrates gave the critical activity a grand start, but he did more than that,’ said Charlie May, rather magisterially. The cronies had such a curious pomposity under their assumed modesty. It was all so ex cathedra, and it all pretended to be so humble.

Dukes refused to be drawn about Socrates.

‘That’s quite true, criticism and knowledge are not the same thing,’ said Hammond.

‘They aren’t, of course,’ chimed in Berry, a brown, shy young man, who had called to see Dukes, and was staying the night.

They all looked at him as if the ass had spoken.

‘I wasn’t talking about knowledge … I was talking about the mental life,’ laughed Dukes. ‘Real knowledge comes out of the whole corpus of the consciousness; out of your belly and your penis as much as out of your brain and mind. The mind can only analyse and rationalize. Set the mind and the reason to cock it over the rest, and all they can do is to criticize, and make a deadness. I say all they can do. It is vastly important. My God, the world needs criticizing today … criticizing to death. Therefore let’s live the mental life, and glory in our spite, and strip the rotten old show. But, mind you, it’s like this: while you live your life, you are in some way an Organic whole with all life. But once you start the mental life you pluck the apple. You’ve severed the connexion between the apple and the tree: the organic connexion. And if you’ve got nothing in your life but the mental life, then you yourself are a plucked apple … you’ve fallen off the tree. And then it is a logical necessity to be spiteful, just as it’s a natural necessity for a plucked apple to go bad.’

Clifford made big eyes: it was all stuff to him. Connie secretly laughed to herself.

‘Well then we’re all plucked apples,’ said Hammond, rather acidly and petulantly.

‘So let’s make cider of ourselves,’ said Charlie.

‘But what do you think of Bolshevism?’ put in the brown Berry, as if everything had led up to it.

‘Bravo!’ roared Charlie. ‘What do you think of Bolshevism?’

‘Come on! Let’s make hay of Bolshevism!’ said Dukes.

‘I’m afraid Bolshevism is a large question,’ said Hammond, shaking his head seriously.

‘Bolshevism, it seems to me,’ said Charlie, ‘is just a superlative hatred of the thing they call the bourgeois; and what the bourgeois is, isn’t quite defined. It is Capitalism, among other things. Feelings and emotions are also so decidedly bourgeois that you have to invent a man without them.

‘Then the individual, especially the personal man, is bourgeois: so he must be suppressed. You must submerge yourselves in the greater thing, the Soviet-social thing. Even an organism is bourgeois: so the ideal must be mechanical. The only thing that is a unit, non-organic, composed of many different, yet equally essential parts, is the machine. Each man a machine-part, and the driving power of the machine, hate … hate of the bourgeois. That, to me, is Bolshevism.’

‘Absolutely!’ said Tommy. ‘But also, it seems to me a perfect description of the whole of the industrial ideal. It’s the factory-owner’s ideal in a nut-shell; except that he would deny that the driving power was hate. Hate it is, all the same; hate of life itself. Just look at these Midlands, if it isn’t plainly written up … but it’s all part of the life of the mind, it’s a logical development.’

‘I deny that Bolshevism is logical, it rejects the major part of the premiss,’ said Hammond.

‘My dear man, it allows the material premiss; so does the pure mind … exclusively.’

‘At least Bolshevism has got down to rock bottom,’ said Charlie.

‘Rock bottom! The bottom that has no bottom! The Bolshevists will have the finest army in the world in a very short time, with the finest mechanical equipment.

‘But this thing can’t go on … this hate business. There must be a reaction…’ said Hammond.

‘Well, we’ve been waiting for years … we wait longer. Hate’s a growing thing like anything else. It’s the inevitable outcome of forcing ideas on to life, of forcing one’s deepest instincts; our deepest feelings we force according to certain ideas. We drive ourselves with a formula, like a machine. The logical mind pretends to rule the roost, and the roost turns into pure hate. We’re all Bolshevists, only we are hypocrites. The Russians are Bolshevists without hypocrisy.’

‘But there are many other ways,’ said Hammond, ‘than the Soviet way. The Bolshevists aren’t really intelligent.’

‘Of course not. But sometimes it’s intelligent to be half-witted: if you want to make your end. Personally, I consider Bolshevism half-witted; but so do I consider our social life in the west half-witted. So I even consider our far-famed mental life half-witted. We’re all as cold as cretins, we’re all as passionless as idiots. We’re all of us Bolshevists, only we give it another name. We think we’re gods … men like gods! It’s just the same as Bolshevism. One has to be human, and have a heart and a penis if one is going to escape being either a god or a Bolshevist … for they are the same thing: they’re both too good to be true.’

Out of the disapproving silence came Berry’s anxious question:

‘You do believe in love then, Tommy, don’t you?’

‘You lovely lad!’ said Tommy. ‘No, my cherub, nine times out of ten, no! Love’s another of those half-witted performances today. Fellows with swaying waists fucking little jazz girls with small boy buttocks, like two collar studs! Do you mean that sort of love? Or the joint-property, make-a-success-of-it, my-husband-my-wife sort of love? No, my fine fellow, I don’t believe in it at all!’

‘But you do believe in something?’

‘Me? Oh, intellectually I believe in having a good heart, a chirpy penis, a lively intelligence, and the courage to say “shit!” in front of a lady.’

‘Well, you’ve got them all,’ said Berry.

Tommy Dukes roared with laughter. ‘You angel boy! If only I had! If only I had! No; my heart’s as numb as a potato, my penis droops and never lifts its head up, I dare rather cut him clean off than say “shit!” in front of my mother or my aunt … they are real ladies, mind you; and I’m not really intelligent, I’m only a “mental-lifer”. It would be wonderful to be intelligent: then one would be alive in all the parts mentioned and unmentionable. The penis rouses his head and says: How do you do? – to any really intelligent person. Renoir said he painted his pictures with his penis … he did too, lovely pictures! I wish I did something with mine. God! when one can only talk! Another torture added to Hades! And Socrates started it.’

‘There are nice women in the world,’ said Connie, lifting her head up and speaking at last.

The men resented it … she should have pretended to hear nothing. They hated her admitting she had attended so closely to such talk.

‘My God! If they be not nice to me what care I how nice they be?’

‘No, it’s hopeless! I just simply can’t vibrate in unison with a woman. There’s no woman I can really want when I’m faced with her, and I’m not going to start forcing myself to it … My God, no! I’ll remain as I am, and lead the mental life. It’s the only honest thing I can do. I can be quite happy talking to women; but it’s all pure, hopelessly pure. Hopelessly pure! What do you say, Hildebrand, my chicken?’

‘It’s much less complicated if one stays pure,’ said Berry.

‘Yes, life is all too simple!’

CHAPTER 5

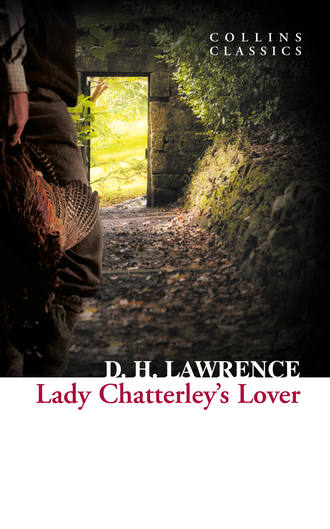

On a frosty morning with a little February sun, Clifford and Connie went for a walk across the park to the wood. That is, Clifford chuffed in his motor-chair, and Connie walked beside him.

The hard air was still sulphurous, but they were both used to it. Round the near horizon went the haze, opalescent with frost and smoke, and on the top lay the small blue sky; so that it was like being inside an enclosure, always inside. Life always a dream or a frenzy, inside an enclosure.

The sheep coughed in the rough, sere grass of the park, where frost lay bluish in the sockets of the tufts. Across the park ran a path to the wood-gate, a fine ribbon of pink. Clifford had had it newly gravelled with sifted gravel from the pit-bank. When the rock and refuse of the underworld had burned and given off its sulphur, it turned bright pink, shrimp-coloured on dry days, darker, crab-coloured on wet. Now it was pale shrimp-colour, with a bluish-white hoar of frost. It always pleased Connie, this underfoot of sifted, bright pink. It’s an ill wind that brings nobody good.

Clifford steered cautiously down the slope of the knoll from the hall, and Connie kept her hand on the chair. In front lay the wood, the hazel thicket nearest, the purplish density of oaks beyond. From the wood’s edge rabbits bobbed and nibbled. Rooks suddenly rose in a black train, and went trailing off over the little sky.

Connie opened the wood-gate, and Clifford puffed slowly through into the broad riding that ran up an incline between the clean-whipped thickets of the hazel. The wood was a remnant of the great forest where Robin Hood hunted, and this riding was an old, old thoroughfare coming across country. But now, of course, it was only a riding through the private wood. The road from Mansfield swerved round to the north.

In the wood everything was motionless, the old leaves on the ground keeping the frost on their underside. A jay called harshly, many little birds fluttered. But there was no game; no pheasants. They had been killed off during the war, and the wood had been left unprotected, till now Clifford had got his game-keeper again.

Clifford loved the wood; he loved the old oak-trees. He felt they were his own through generations. He wanted to protect them. He wanted this place inviolate, shut off from the world.

The chair chuffed slowly up the incline, rocking and jolting on the frozen clods. And suddenly, on the left, came a clearing where there was nothing but a ravel of dead bracken, a thin and spindly sapling leaning here and there, big sawn stumps, showing their tops and their grasping roots, lifeless. And patches of blackness where the woodmen had burned the brushwood and rubbish.

This was one of the places that Sir Geoffrey had cut during the war for trench timber. The whole knoll, which rose softly on the right of the riding, was denuded and strangely forlorn. On the crown of the knoll where the oaks had stood, now was bareness; and from there you could look out over the trees to the colliery railway, and the new works at Stacks Gate. Connie had stood and looked, it was a breach in the pure seclusion of the wood. It let in the world. But she didn’t tell Clifford.

This denuded place always made Clifford curiously angry. He had been through the war, had seen what it meant. But he didn’t get really angry till he saw this bare hill. He was having it replanted. But it made him hate Sir Geoffrey.

Clifford sat with a fixed face as the chair slowly mounted. When they came to the top of the rise he stopped; he would not risk the long and very jolty down-slope. He sat looking at the greenish sweep of the riding downwards, a clear way through the bracken and oaks. It swerved at the bottom of the hill and disappeared; but it had such a lovely easy curve, of knights riding and ladies on palfreys.

‘I consider this is really the heart of England,’ said Clifford to Connie, as he sat there in the dim February sunshine.

‘Do you?’ she said, seating herself in her blue knitted dress, on a stump by the path.

‘I do! this is the old England, the heart of it; and I intend to keep it intact.’

‘Oh yes!’ said Connie. But, as she said it she heard the eleven-o’clock hooters at Stacks Gate colliery. Clifford was too used to the sound to notice.

‘I want this wood perfect … untouched. I want nobody to trespass in it,’ said Clifford.

There was a certain pathos. The wood still had some of the mystery of wild, old England; but Sir Geoffrey’s cuttings during the war had given it a blow. How still the trees were, with their crinkly, innumerable twigs against the sky, and their grey, obstinate trunks rising from the brown bracken! How safely the birds flitted among them! And once there had been deer, and archers, and monks padding along on asses. The place remembered, still remembered.