Полная версия

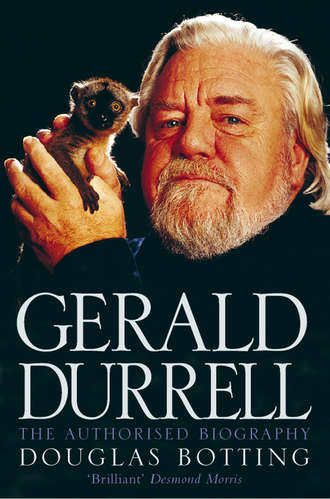

Gerald Durrell: The Authorised Biography

‘I believe you have the brother of a friend of mine at your school,’ said Alan.

‘Oh?’ said the headmaster. ‘What’s his name?’

‘Durrell. Gerald Durrell,’ Alan replied.

‘The most ignorant boy in the school,’ snapped the headmaster, and stalked out of the shop.

Gerald stumbled with difficulty through his lessons, until one day, falsely accused of a misdemeanour by the school sneak and given six of the best on his bare bottom by the headmaster, his mother took the mortified boy away from the school for good, thus terminating his formal schooling for ever at the age of nine.

To help Gerald get over the trauma of his beating, Mother decided to buy him a present, and took him down on the tram to Bournemouth town centre to choose a dog at the pet shop. Gerald recalled:

There was a whole litter of curly-headed black puppies in the window and I stood for a long time wondering which one I should buy. At length I decided on the smallest one, the one that was getting the most bullying from the others, and he was purchased for the noble sum of ten shillings. I carried him home in triumph and christened him Roger and he turned out to be one of the most intelligent, brave and lovely dogs that I have ever had. He grew rapidly into something resembling a small Airedale covered with the sort of curls you find on a poodle. He was very intelligent and soon mastered several tricks, such as dying for King and Country.

Roger was destined one day to become famous – and, in a sense, immortal.

Relieved of the intolerable burden of schooling, Gerald reverted to his normal cheerful, engaging self, exploring the garden, climbing the trees, playing with his dog, roaming around the house with his pockets full of slugs and snails, dreaming up pranks. It was Gerald, Dorothy Brown recalled, who would put stink-bombs in the coal scuttle when he came over with the family for Christmas. Mother presided over the moveable feast that was life at Dixie Lodge. ‘No one was ever turned away from her table,’ Dorothy remembered, ‘and all her children’s friends were always welcome. “How many of you can come round tonight?” she would ask, and they would all sit down, young and old together. Mother was very small but she had a very big heart. She was very friendly and a good mixer and she was a wonderful cook.’

The delicious aromas that drifted out of Mother’s kitchen, the range and quality of the dishes she brought to the dining table, and the enthusiasm, good cheer and riotous conversation enjoyed by the company that sat down at that table had a deep and permanent impact on her youngest child. Gerald emerged into maturity as if he had been born a gourmet and a gourmand. Much of her cooking Louisa had learned from her mother, the rest from her Indian cooks in the kitchens of her various homes, where she would secretly spend hours behind her disapproving husband’s back. When she returned to England she brought with her the cookbooks and notebooks she had carted around the subcontinent during her itinerant life there. Some of Louisa’s favourite recipes – English, Anglo-Indian and Indian – had been copied out in a perfect Victorian copperplate by her mother: ‘Chappatis’, ‘Toffy’, ‘A Cake’, ‘Milk Punch’, ‘German Puffs’, ‘Jew Pickle’ (prunes, chillies, dates, mango and green ginger). Most, though, were in her own hand, and embraced the cuisine of the world, from ‘Afghan Cauliflower’, ‘Indian Budgees’ and ‘American Way of Frying Chicken’ to ‘Dutch Apple Pudding’, ‘Indian Plum Cake’, ‘Russian Sweet’, ‘All Purpose Cake’, ‘Spiral Socks’ (a mysterious entry) and ‘Baby’s Knitted Cap’ (another). But Indian cookery was her tour de force and alcoholic concoctions her hobby: dandelion wine, raisin wine, ginger wine (requiring six bottles of rum) and daisy wine (four quarts of daisy blossoms, yeast, lemons, mangoes and sugar).

Not surprisingly, Alan Thomas was soon spending almost every evening and weekend with the family. They were, he quickly realised, a most extraordinary bunch:

There never was more generous hospitality. Nobody who has known the family at all well can deny that their company is ‘life-enhancing’. All six members of the family were remarkable in themselves, but in lively reaction to each other the whole was greater than the sum of the parts. Amid the gales of Rabelaisian laughter, the wit, Larry’s songs accompanied by piano or guitar, the furious arguments and animated conversation going on long into the night, I felt that life had taken on a new dimension.

At this time Lawrence was writing, Margaret rebelling about returning to school, and Leslie ‘crooning, like a devoted mother, over his new collection of firearms’. As for Gerald, though he was still tender in years he was already a great animal collector, and every washbasin in the house was filled with newts, tadpoles and the like.

‘While one could hardly say that Mrs Durrell was in control of the family,’ Alan recalled, ‘it was her warm-hearted character, her amused but loving tolerance that held them together; even during the occasional flare-ups of Irish temper. I remember Gerry, furious with Larry who, wanting to wash, pulled the plug out of a basin full of marine life. Spluttering with ungovernable rage, almost incoherent, searching for the most damaging insult in his vocabulary: “You, you (pause), you AUTHOR, YOU.’”

But the boy Gerald owed much to his big brother’s selfless and unstinting support: ‘Years ago when I was six or seven years old and Larry was a struggling and unknown writer, he would encourage me to write. Spurred on by his support, I wrote a fair bit of doggerel in those days and Larry always treated these effusions with as much respect as if they had just come from the pen of T.S. Eliot. He would always stop whatever work he was engaged upon to type my jingles out for me and so it was from Larry’s typewriter that I first saw my name, as it were, in print.’

Near the end of his life, with more than half the family now dead, Gerald looked back with fondness and frankness at the turmoil of his childhood days, scribbling a fleeting insight in a shaky hand on a yellow restaurant paper napkin: ‘My family was an omelette of rages and laughter entwined with a curious love – an amalgam of stupidity and love.’

At about the time Mother bought Dixie Lodge, Lawrence met Nancy Myers, an art student at the Slade, slightly younger than him and very like Greta Garbo to look at – tall, slim, blonde, blue-eyed. Just turned twenty, Lawrence was living a dedicatedly Bohemian, aspiringly artistic existence in London, playing jazz piano in the Blue Peter nightclub, scribbling poetry, grappling with his first novel and reading voraciously under the great dome of the British Library. ‘My so-called upbringing was quite an uproar,’ he was to recall. ‘I have always broken stable when I was unhappy. I hymned and whored in London. I met Nancy in an equally precarious position and we struck up an incongruous partnership.’ Soon he and Nancy were sharing a bedsit in Guilford Street, near Russell Square. ‘Well, we did a bit of drinking and dying. Ran a photographic studio together. It crashed. Tried posters, short stories, journalism – everything short of selling our bottoms to clergymen. I wrote a cheap novel. Sold it – well that altered things. Here was a stable profession for me to follow. Art for money’s sake.’

Before long Lawrence decided it was time Nancy was given her baptism of fire and shown off to the family. Many years later, Nancy vividly remembered her introduction to that unforgettable ménage.

We drove down in the car for the weekend. I was fascinated to be meeting this family, because Larry dramatised everything – mad mother, ridiculous children, mother drunk, throwing their fortune to the winds, getting rid of everything … hellish, foolish, stupid woman. I mean, it’s wonderful to hear anybody talking about their family like that, and I was very thrilled.

The house had no architectural merit at all, but the rooms were a fair size, and they had a certain amount of comfort – a rather disarray sort of comfort. I mean, they had a few easy chairs and a sofa in the sitting-room and the floors were carpeted and things. It all seemed a little bit makeshift somehow. But I remember I loved the house – the sort of craziness of it, people sort of playing at keeping house rather than really keeping house. You felt they weren’t forced into any mould like people usually are – every sort of meal was at a different time, and everybody was shouting at everybody else, no control anywhere.

Really it was the first time I’d been in a family – in a jolly family – and the first time that I’d been able to say what I liked – there was nothing forbidden to say. It was a great opening-up experience for me, hearing everybody saying ‘You bloody fool!’ to everybody else, and getting away with it. It was marvellous. So I really fell in love with the family.

Gerry was six or seven at the time – a very slender, very delicate, very charming little boy who looked a bit like Christopher Robin and was too sensitive to go to school. Even at that time there was quite a lot of friction between Larry and Leslie, and Larry used to tease his brother mercilessly. Leslie was never very quick-witted, and Larry would make him look a fool any time he liked, and any time Leslie crossed him he used to absolutely flay him, which Leslie minded very much.

But my first visit ended in disaster. On our first morning Larry came into my room and hopped into bed with me, and then Gerry came along and hopped into bed too, so we were all sort of cosy under the blankets, cuddled together, the three of us, and this was too much for Mother. She came in and said she’d never been so disgusted in her life. ‘What a way to behave!’ she said, shouting. ‘Out you go, out you go this minute, out you both go, five minutes and you must get out, I’m not having Gerry corrupted!’ She could have histrionics when she wanted to.

I was a bit abashed, feeling terrible about it, but Larry said, ‘Oh, the silly woman, she’ll get over it. Come on, we’ll go. She’ll get over it in a day and be pleased to have us back. Silly nothing – just like a stupid woman. Don’t be such a fool, Mother …’

So we sort of tiptoed out of the house – but within a fortnight or so we were welcomed back, and you know, Mother closed her eyes to whatever we were doing from then onwards. And she was terribly sweet to me. I mean, I always felt rather like a goose among ducklings – they were all so small and I was so long and thin. But they couldn’t have been sweeter. After that first moment Mother was always clucking over me. She thought I looked consumptive and used to give me lots of gold-top milk and butter and fill me up with cream and Weetabix and whatever was going. And she was a marvellous cook; she did most of the cooking, a lot of hot stuff, curries, Indian cooking …

I just loved the whole craziness of it. Mother used to drink a lot of gin at that time, and she used to retire to bed when Gerry went to bed – Gerry wouldn’t go to bed without her, he was afraid of being on his own, I think – and she’d take her gin bottle up with her when she went. So then we all used to retire up there, carrying a gin bottle up to bed. She had a large double bed, and an enormous silver tea-tray with lots of silver teapots and things on it, and we’d carry on the evening sitting on the bed, drinking gin and tea and chatting, while Gerry was asleep in his own bed in the same room. I think he must have been able to go to sleep if there was a noise going on. It was all very cosy.

Though friends might adore the Durrells, the wider family – the cohort of aunts and grannies – disapproved mightily. They were appalled at Mother’s incompetence and extravagance when it came to money, dismayed that she would not help her cousin Fan out of her penury, and scandalised at the way she was bringing up her children – her lack of control; their wild, undisciplined ways; the outrageous Bohemian ambience of her household, as they saw it, doubly shocking in the deathly polite context of suburban Bournemouth. Leslie especially was a cause for concern. One cousin, Molly Briggs, the daughter of Gerald’s father’s sister Elsie, remembered:

Leslie drove Aunt Lou mad at this time, staying in bed till midday and slouching about. He never settled to anything, never saw anything through. As children my sister and I didn’t like him very much. Sometimes he would condescend to play with us, but you never knew from one minute to the next how he would behave. He would suddenly turn nasty for no reason at all. Both Gerry and Leslie ran rings round Aunt Lou and were quite unmanageable, But Gerry was a beautiful little boy, really, and great fun. He used to shin up a tree where he had a secret place we didn’t dare follow him to. And he used to play with three slow worms, fondling them and winding them around his hands. We had been brought up in Ceylon to fear snakes, so were terrified of Gerry’s pets and wouldn’t touch them. I remember we learned to ride a bike with Gerry on a sunken lawn surrounded by heather banks. We were terribly noisy and shrieked with laughter whenever we fell over, which was very often, so eventually Larry, who was probably composing something, leaned out of an upstairs window and shouted: ‘Stop that bloody row!’

‘It’s curious – something one didn’t realise at the time – but my mother allowed us to be,’ Gerald recalled.

She worried over us, she advised (when we asked) and the advice always ended with, ‘But anyway, dear, you must do what you think best.’ It was, I suppose, a form of indoctrination, a form of guidance. She opened new doors on problems that allowed new explorations of ways in which you might – or might not – deal with them – simple things now ingrained in me without a recollection of how they got there. I was never lectured, never scolded.

Lawrence and Nancy had been living for a year with their friends George and Pam Wilkinson in a cottage at Loxwood in Sussex, where Lawrence wrote his first novel, a novice work called Pied Piper of Lovers, which was published in 1935. At the end of 1934 the Wilkinsons had struck camp and moved on, emigrating to the Greek island of Corfu, where the climate was good, the exchange rate favourable and the living cheap and easy. Lawrence and Nancy, meanwhile, moved in with the family at Dixie Lodge. From time to time a letter would arrive from George Wilkinson describing the idyllic life they were leading on their beautiful, verdant and as yet unspoilt island, and gradually the idea began to grow – in Lawrence’s mind first – that perhaps that was where he and Nancy should live and have their being, a perfect retreat for a young aspiring writer and a young aspiring painter, both of them keen to learn what they could of ancient Greek art and archaeology. There was nothing to keep Lawrence in England. It was not the land of his birth, he had no roots there, and there was much about the place and the English outlook and way of life – ‘the English way of death’, he called it – that he had detested from the moment he set foot there as a lonely, bewildered boy of eleven, exiled from his native India to begin his formal education at ‘home’. ‘Pudding Island’ was his dismissive term for Britain. ‘That mean, shabby little island,’ he was to tell a friend much later, ‘wrung my guts out of me and tried to destroy anything singular and unique in me.’ Its dismal climate alone was reason enough to move on. ‘Alan,’ he had remarked to Alan Thomas after receiving a letter from George Wilkinson describing the orange groves surrounding his villa, ‘think of the times in England when everybody you know has a cold.’ Though the running was made by Lawrence, the idea of moving to Corfu soon took hold of the whole family.

While his mother was still alive, Gerald’s version of events described a kind of mass migration to the sun dreamed up and pushed through by his eldest brother. It had all begun, he was to relate in a famous passage, on a day of a leaden August sky. ‘A sharp, stinging drizzle fell,’ he wrote, ‘billowing into opaque grey sheets when the wind caught it. Along the Bournemouth seafront the beach-huts turned blank wooden faces towards a greeny-grey, froth-chained sea that leapt eagerly at the cement bulwark of the shore. The gulls had been tumbled inland over the town, and they now drifted above the housetops on taut wings, whining peevishly. It was the sort of weather calculated to try anyone’s endurance.’

At Dixie Lodge the family were assembled – ‘not a very prepossessing sight that afternoon’. For Gerald the weather had brought on catarrh, and he was forced to breath ‘stertorously’ through open mouth. For Leslie it had inflamed his ears so that they bled. For Margaret it had brought a fresh blotch of acne. For Mother it had generated a bubbling cold and a twinge of rheumatism. Only Larry was as yet unscathed, and as the afternoon wore on his irritation grew till he was forced to declaim: ‘Why do we stand this bloody climate? Look at it! And, if it comes to that, look at us … Really, it’s time something was done. I can’t be expected to produce deathless prose in an atmosphere of doom and eucalyptus … Why don’t we pack up and go to Greece?’

After his mother’s death Gerald was to give an alternative – or perhaps additional – motive for the idea. Mother, it seems, had found some grown-up consolation and companionship at Dixie Lodge, in the company of Lottie, the family’s Swiss maid. But then Lottie’s husband fell ill – Gerald thought with cancer – and Lottie had no option but to leave Mother’s employ in order to help look after her husband. ‘So back to square one,’ Gerald wrote in his unpublished memoir:

Lonely evenings, where Mother had only myself, aged nine, as company. So loneliness, of course, nudged Mother closer and closer to the Demon Drink. Larry, recognising the pitfalls, decided that decisive action must be taken and told Mother he thought we ought to up sticks and go and join George in Corfu. Mother, as usual, was hesitant.

‘What am I supposed to do with the house?’ she asked.

‘Sell it before it gets into a disreputable state,’ said Larry. ‘I think it is essential that we make this move.’

Larry himself gave a third, perhaps more cogent reason for emigrating, which he explained in a note to George Wilkinson out in Corfu: ‘The days are so dun and gloomy that we pant for the sun,’ he wrote. ‘My mother has gotten herself into a really good financial mess and has decided to cut and run for it. Being too timid to tackle foreign landscapes herself, she wants to be shown around the Mediterranean by us. She wants to scout Corfu. If she likes it I have no doubt but that she’ll buy the place …’

It is very likely that all three pressures – booze, money and sun – played their part in the final decision. But Mother did not need a great deal of persuading. She always hated to say no, Lawrence said, and in any case there was not much to keep her in England. In fact there wasn’t much to keep any of them there, for they were all exiles from Mother India, and none of them had sunk many roots in the Land of Hope and Glory. ‘It was a romantic idea and a mammoth decision,’ Margaret was to relate. ‘I should have been going back to school at Malvern but I said, “I’m not going to be left out!” and Mother, being a bit like that about everything, agreed.”’

So the decision was made. The whole family would go – Larry and Nancy, Mother, Leslie (who would be eighteen by the time they sailed), Margaret (fifteen) and Gerald (ten). When Larry replied to George Wilkinson’s invitation to move to Corfu, he asked about schooling for Gerry. A little alarmed, Wilkinson replied: ‘D’you all intend coming(!) and how many is all?’ But it was all or none. The house was put up for sale and goods and chattels crated up and shipped out ahead to Corfu.

The fate of the animals of the household presented a major headache, especially for Gerald, to whom they all belonged. The white mice were given to the baker’s son, the wigged canary to the man next door, Pluto the spaniel to Dr Macdonald, the family GP, and Billie the tortoise to Lottie in Brighton, who twenty-seven years later, when Gerald was famous, wrote to ask if he wanted it back, adding: ‘You have always loved animals, even the very smallest of them, so at least I know you couldn’t be anything but kind.’ Only Roger the dog would be going off with the family, complete with an enormous dog passport bearing a huge red seal.

Lawrence and Nancy were due to go out as the vanguard early in 1935. While they were living in Dixie Lodge prior to departure they decided to marry in secret – perhaps to keep the news from Nancy’s parents, who may have disapproved of such a raffish and Bohemian husband for their beautiful daughter. The marriage took place on 22 January at Bournemouth Register Office. Alan Thomas was sworn to secrecy and asked to act as witness. There was some anxiety before the wedding that because Alan and Nancy were so tall and Lawrence so short, the registrar might marry the wrong pair without realising it. ‘With a view to avoiding any such contingency,’ recalled Alan, ‘we approached a couple of midgets, then appearing in a freak-show at the local fun-fair, and asked them to appear as witnesses; but their employer refused to allow such valuable assets out of his sight.’

On 2 March 1935 Lawrence and Nancy set sail from Tilbury on board the P&O liner SS Oronsay, bound for Naples on the first stage of their journey to Corfu. Within the week the rest of the family were also en route. On 6 March they checked into the Russell Hotel in London, from where, the following day, Leslie sent Alan Thomas a postcard: ‘We are going to catch the boat this evening (with luck). P.S. Note the address – we are getting up in the world – 12/6 a night bed and etc!!!!’

In his published account of the family’s Corfu adventure, Gerald gives the impression they travelled overland across France, Switzerland and Italy. In fact Mother, Leslie, Margaret, Gerald and Roger the dog sailed from Tilbury, travelling second class on board a Japanese cargo boat, the SS Hakone Maru of the NYK Line, bound for Naples. Leslie seems to have been the only Durrell on board who was up to writing, and his postcards and other missives constitute virtually his last recorded utterance in this history. Chugging through the Dover Straits he told Alan Thomas on 8 March: ‘So far I have a cabin of my own. The people in the Second Class are quite nice and very jolly. The ship’s rolling a bit but the Durrells are all fine.’

Two days later, butting their way across the Bay of Biscay, the adventure was hotting up nicely. ‘We had a heavy snow storm this morning,’ wrote Leslie, ‘and we had to go up to the top deck where the lifeboats are and give that ******* dog some exercise. God what a time we had, what with the dog piddling all over the place, the snow coming down, the old wind blowing like HELL – God what a trip! No one seemed to know what to do at lifeboat drill, so if anything goes wrong it will only be with the Grace of God (if there is one) if any of us see the dear coast of Old England again.’

By 15 March, after a trip ashore at Gibraltar – ‘none of the Durrells sick so far, not even that ******* dog,’ reported Leslie – they had reached Marseilles. Next stop Naples, the train to Brindisi and the ferry to Corfu, 130 miles away across the Strait of Otranto and the Ionian Sea

It was an overnight run. ‘The tiny ship throbbed away from the heel of Italy,’ Gerald recalled of that fateful crossing, ‘out into the twilit sea, and as we slept in our stuffy cabins, somewhere in that tract of moon-polished water we passed the invisible dividing-line and entered the bright, looking-glass world of Greece. Slowly this sense of change seeped down to us, and so, at dawn, we awoke restless and went on deck.’ For a long time the island was just a chocolate-brown smudge of land, huddled in mist on the starboard bow.

Then suddenly the sun shifted over the horizon and the sky turned the smooth enamelled blue of a jay’s eye … The mist lifted in quick, lithe ribbons, and before us lay the island, the mountains sleeping as though beneath a crumpled blanket of brown, the folds stained with the green of olive-groves. Along the shore curved beaches as white as tusks among tottering cities of brilliant gold, red, and white rocks … Rounding the cape we left the mountains, and the island sloped gently down, blurred with silver and green iridescence of olives, with here and there an admonishing finger of black cypress against the sky. The shallow sea in the bays was butterfly blue, and even above the sound of the ship’s engines we could hear, faintly ringing from the shore like a chorus of tiny voices, the shrill, triumphant cries of the cicadas.