Полная версия

The Sonnets

Life & Times

William Shakespeare the Playwright

There exists a curious paradox when it comes to the life of William Shakespeare. He easily has more words written about him than any other famous English writer, yet we know the least about him. This inevitably means that most of what is written about him is either fabrication or speculation. The reason why so little is known about Shakespeare is that he wasn’t a novelist or a historian or a man of letters. He was a playwright, and playwrights were considered fairly low on the social pecking order in Elizabethan society. Writing plays was about providing entertainment for the masses – the great unwashed. It was the equivalent to being a journalist for a tabloid newspaper.

In fact, we only know of Shakespeare’s work because two of his friends had the foresight to collect his plays together following his death and have them printed. The only reason they did so was apparently because they rated his talent and thought it would be a shame if his words were lost.

Consequently his body of work has ever since been assessed and reassessed as the greatest contribution to English literature. That is despite the fact that we know that different printers took it upon themselves to heavily edit the material they worked from. We also know that Elizabethan plays were worked and reworked frequently, so that they evolved over time until they were honed to perfection, which means that many different hands played their part in the active writing process. It would therefore be fair to say that any play attributed to Shakespeare is unlikely to contain a great deal of original input. Even the plots were based on well known historical events, so it would be hard to know what fragments of any Shakespeare play came from that single mind.

One might draw a comparison with the Christian bible, which remains such a compelling read because it came from the collaboration of many contributors and translators over centuries, who each adjusted the stories until they could no longer be improved. As virtually nothing is known of Shakespeare’s life and even less about his method of working, we shall never know the truth about his plays. They certainly contain some very elegant phrasing, clever plot devices and plenty of words never before seen in print, but as to whether Shakespeare invented them from a unique imagination or whether he simply took them from others around him is anyone’s guess.

The best bet seems to be that Shakespeare probably took the lead role in devising the original drafts of the plays, but was open to collaboration from any source when it came to developing them into workable scripts for effective performances. He would have had to work closely with his fellow actors in rehearsals, thereby finding out where to edit, abridge, alter, reword and so on.

In turn, similar adjustments would have occurred in his absence, so that definitive versions of his plays never really existed. In effect Shakespeare was only responsible for providing the framework of plays, upon which others took liberties over time. This wasn’t helped by the fact that the English language itself was not definitive at that time either. The consequence was that people took it upon themselves to spell words however they pleased or to completely change words and phrasing to suit their own preferences.

It is easy to see then, that Shakespeare’s plays were always going to have lives of their own, mutating and distorting in detail like Chinese whispers. The culture of creative preservation was simply not established in Elizabethan England. Creative ownership of Shakespeare’s plays was lost to him as soon as he released them into the consciousness of others. They saw nothing wrong with taking his ideas and running with them, because no one had ever suggested that one shouldn’t, and Shakespeare probably regarded his work in the same way. His plays weren’t sacrosanct works of art, they were templates for theatre folk to make their livings from, so they had every right to mould them into productions that drew in the crowds as effectively as possible. Shakespeare was like the helmsman of a sailing ship, steering the vessel but wholly reliant on the team work of his crew to arrive at the desired destination.

It seems that Shakespeare certainly had a natural gift, but the genius of his plays may be attributable to the collective efforts of Shakespeare and others. It is a rather satisfying notion to think that his plays might actually be the creative outpourings of the Elizabethan milieu in which Shakespeare immersed himself. That makes them important social documents as well as seminal works of the English language.

Money in Shakespeare’s Day

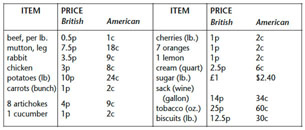

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to relate the value of money in our time to its value in another age and to compare prices of commodities today and in the past. Many items are simply not comparable on grounds of quality or serviceability.

There was a bewildering variety of coins in use in Elizabethan England. As nearly all English and European coins were gold or silver, they had intrinsic value apart from their official value. This meant that foreign coins circulated freely in England and were officially recognized, for example the French crown (écu) worth about 30p (72 cents), and the Spanish ducat worth about 33p (79 cents). The following table shows some of the coins mentioned by Shakespeare and their relation to one another.

A comparison of the following prices in Shakespeare’s time with the prices of the same items today will give some idea of the change in the value of money.

TO. THE. ONLIE. BEGETTER. OF.

THESE. INSUING. SONNETS.

MR. W. H. ALL. HAPPINESSE.

AND. THAT. ETERNITIE.

PROMISED.

BY. OUR. EVER-LIVING. POET.

WISHETH.

THE. WELL-WISHING.

ADVENTURER. IN.

SETTING.

FORTH.

T.T.

1

FROM fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory;

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

2

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery, so gaz’d on now,

Will be a tatter’d weed of small worth held.

Then being ask’d where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

To say within thine own deep-sunken eyes

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserv’d thy beauty’s use,

If thou couldst answer ‘This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count, and make my old excuse’

Proving his beauty by succession thine!

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.

3

Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love, to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live rememb’red not to be,

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

4

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thyself thy beauty’s legacy?

Nature’s bequest gives nothing, but doth lend,

And, being frank, she lends to those are free.

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless unsurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thyself alone,

Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unus’d beauty must be tomb’d with thee,

Which, used, lives th’ executor to be.

5

Those hours that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell

Will play the tyrants to the very same,

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter, and confounds him there;

Sap check’d with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnow’d, and bareness every where.

Then, were not summer’s distillation left

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was;

But flowers distill’d, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show: their substance still lives sweet.

6

Then let not winter’s ragged hand deface

In thee thy summer ere thou be distill’d;

Make sweet some vail; treasure thou some place

With beauty’s treasure ere it be self-kill’d.

That use is not forbidden usury

Which happies those that pay the willing loan –

That’s for thyself to breed an other thee,

Or ten times happier, be it ten for one;

Ten times thyself were happier than thou art,

If ten of thine ten times refigur’d thee.

Then what could Death do if thou shouldst depart,

Leaving thee living in posterity?

Be not self-will’d, for thou art much too fair

To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir.

7

Lo, in the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight,

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

And having climb’d the steep-up heavenly hill;

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

Attending on his golden pilgrimage;

But when from higmost pitch, with weary car,

Like feeble age he reeleth from the day,

The eyes, ‘fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract and look another way;

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon,

Unlook’d on diest, unless thou get a son.

8

Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy.

Why lov’st thou that which thou receiv’st not gladly,

Or else receiv’st with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering;

Resembling sire, and child, and happy mother,

Who, all in one, one pleasing note do sing;

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: ‘Thou single wilt prove none’.

9

Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye

That thou consum’st thyself in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shall hap to die,

The world will wail thee like a makeless wife:

The world will be thy widow, and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep,

By children’s eyes, her husband’s shape in mind.

Look what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty’s waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unus’d, the user so destroys it.

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murd’rous shame commits.

10

For shame! deny that thou bear’st love to any,

Who for thy self art so unprovident.

Grant, if thou wilt, thou art belov’d of many,

But that thou none lov’st is most evident;

For thou art so possess’d with murd’rous hate

That ‘gainst thyself thou stick’st not to conspire,

Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate

Which to repair should be thy chief desire.

O, change thy thought, that I may change my mind!

Shall hate be fairer lodg’d than gentle love?

Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind,

Or to thy self at least kind-hearted prove;

Make thee an other self for love of me,

That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

11

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.