Полная версия

Selected Fairy Tales

SELECTED FAIRY TALES

Hans Christian Andersen

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2014

Life & Times section © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Silvia Crompton asserts her moral right as author of the Life & Times section

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases adapted from Collins English Dictionary

Cover by e-Digital Design

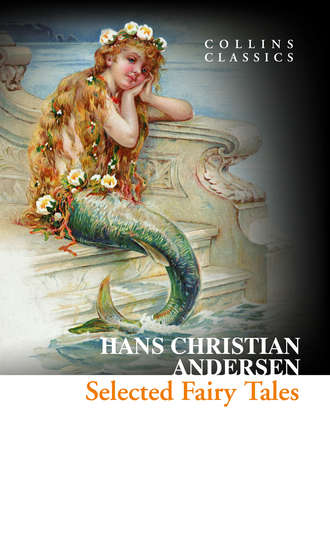

Cover image: Little Mermaid, by Hans Christian Andersen (1805–75) (colour litho), Hardy, E. S. (19th century) / Private Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007558155

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007558162

Version: 2014-07-30

History of Collins

In 1819, millworker William Collins from Glasgow, Scotland, set up a company for printing and publishing pamphlets, sermons, hymn books, and prayer books. That company was Collins and was to mark the birth of HarperCollins Publishers as we know it today. The long tradition of Collins dictionary publishing can be traced back to the first dictionary William published in 1824, Greek and English Lexicon. Indeed, from 1840 onwards, he began to produce illustrated dictionaries and even obtained a licence to print and publish the Bible.

Soon after, William published the first Collins novel, Ready Reckoner; however, it was the time of the Long Depression, where harvests were poor, prices were high, potato crops had failed, and violence was erupting in Europe. As a result, many factories across the country were forced to close down and William chose to retire in 1846, partly due to the hardships he was facing.

Aged 30, William’s son, William II, took over the business. A keen humanitarian with a warm heart and a generous spirit, William II was truly “Victorian” in his outlook. He introduced new, up-to-date steam presses and published affordable editions of Shakespeare’s works and The Pilgrim’s Progress, making them available to the masses for the first time. A new demand for educational books meant that success came with the publication of travel books, scientific books, encyclopedias, and dictionaries. This demand to be educated led to the later publication of atlases, and Collins also held the monopoly on scripture writing at the time.

In the 1860s Collins began to expand and diversify and the idea of “books for the millions” was developed. Affordable editions of classical literature were published, and in 1903 Collins introduced 10 titles in their Collins Handy Illustrated Pocket Novels. These proved so popular that a few years later this had increased to an output of 50 volumes, selling nearly half a million in their year of publication. In the same year, The Everyman’s Library was also instituted, with the idea of publishing an affordable library of the most important classical works, biographies, religious and philosophical treatments, plays, poems, travel, and adventure. This series eclipsed all competition at the time, and the introduction of paperback books in the 1950s helped to open that market and marked a high point in the industry.

HarperCollins is and has always been a champion of the classics, and the current Collins Classics series follows in this tradition – publishing classical literature that is affordable and available to all. Beautifully packaged, highly collectible, and intended to be reread and enjoyed at every opportunity.

Life & Times

It is almost impossible nowadays to pass through childhood without the companionship of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tale creations: the plucky Ugly Duckling, the beautiful Little Mermaid, the foolish Emperor in his ‘new clothes’. A welcome salve to the gorier excesses of the Brothers Grimm, Andersen has for almost two centuries enchanted children – and adults – as a satirist, teller of fantastical tales, moral guide and bringer of hope into the bleakest of beginnings. But for one so treasured by his readers, Andersen led a life of remarkable solitude: he dragged himself from rags to riches and drew widely on the experience in his stories, but he was never able to shake off the mantle of lonely eccentric – a man much admired but rarely loved. His was, in effect, a fairy tale without the happy ending.

The Danish Dickens

Andersen knew he had made it as a writer during an 1847 visit to England, where he was invited to a grand society party and introduced to Charles Dickens. The great novelist, described in Andersen’s diary as ‘the living English writer whom I love the most’, appeared just as captivated by his Danish counterpart and the two began a correspondence that lasted ten years.

As an author, Andersen shared a number of themes with Dickens – notably childhood, poverty, social injustice and reversals of fortune – and in later life both men carved out second careers giving wildly popular public readings, but Andersen had in addition suffered an upbringing worthy of a Dickensian hero. Born in Odense, Denmark, in 1805, he was the only child of a shoemaker and a washerwoman of no fixed address. He made sporadic appearances at charity schools until the age of eleven, when he was forced by his father’s death to find work, first at a cloth mill and then a tobacco factory. Determined to escape the crippling poverty into which he had been born, he stowed away in a wagon bound for Copenhagen at the age of just fourteen, hoping to find his fortune.

Luck and Perseverance

That Andersen was able to become the author of his own destiny is thanks in large part to a series of fortuitous encounters along the way, beginning with his father, Hans. The young Andersen may have been an unenthusiastic schoolboy, but in the evenings Andersen Senior instilled in him a passion for extraordinary stories, reading to him from the Arabian Nights, the fables of Jean de la Fontaine and the Bible – though one of his favourite yarns, unproven to this day, was that the family was descended from Danish nobility. Even when he was sent out to make money, the boy enjoyed sharing folk tales with his adult co-workers, many of which influenced the stories he went on to write.

Life in Odense was certainly hard, but Denmark’s second city was at least large enough to have its own theatre – one that attracted travelling performers from the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen – and Andersen made his first visit there aged seven. By the time he arrived in the capital in 1819, his only dream was to join the theatre as a dancer, singer, actor or writer.

The dream almost foundered on day one, when Andersen performed a disastrous ballet audition at the Royal Theatre and was thrown out. Armed with a letter of recommendation from an Odense printer, however, he persisted in his attempts to infiltrate the institution and was rewarded with a place at the School of Singing and Dance – a place that was revoked nine months later when his voice began to break. Still he refused to leave, enduring a string of non-speaking stage roles while improving his reading and writing. In turning down Andersen’s first play in 1822, one director remarked that the boy nevertheless showed ‘an unmistakable aptitude for writing’.

That same year, the Royal Theatre finally gave Andersen a break. Though his second play was likewise turned down, the rejection came with a recommendation that he be sent to grammar school for a proper education. Having arranged for him to receive a generous grant, the theatre’s director became his guardian and mentor, overseeing his seven years at school and university. Of greatest value during this time, however, was Andersen’s acquaintance and then friendship with the lecturer B.S. Ingemann, who in 1820 had published Denmark’s greatest collection of fairy tales – an accolade his protégée would soon usurp.

Fairy Tales

In February 1835 Andersen wrote to Ingemann: ‘I have started some fantastic tales for children and believe I have succeeded. I have told a couple of tales which as a child I was happy about, and which I do not believe are known, and have written them exactly the way I would tell them to a child.’ His first collection of ‘eventyr’ (‘fantastic tales’) appeared later that year. (‘Fairy tale’ comes from the ‘contes de fées’ of a French writer, Madame d’Aulnoy, in the late seventeenth century.)

Unlike the Brothers Grimm, whose fairy tales, published during Andersen’s childhood, were almost exclusively based on ancient German folk stories, Andersen’s ‘eventyr’ took their inspiration from a wide range of sources. Some, such as ‘The Princess and the Pea’, were taken from tales he had heard as a boy; others, including ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ and ‘Thumbelina’, were adapted from foreign stories – a medieval Spanish tale and the English ‘Tom Thumb’ respectively. But Andersen was above all a master of invention: some of his greatest tales, including ‘The Little Mermaid’ and ‘The Ugly Duckling’, were entirely his own, while ‘The Little Match Girl’ was inspired by a popular woodcut.

Critics derided the 1835 collection for its simplistic language, and sales would have discouraged anyone other than the resilient Andersen, who instead continued to hone his craft and publish. By 1843, when he produced his masterpiece, ‘The Ugly Duckling’, his fairy tales were, in his own words, ‘selling like hot cakes’.

The Ugly Duckling

A regular guest at palaces and parties, Andersen was feted wherever he went; in 1866 he was granted the freedom of the city of Odense, despite having rarely gone back. But he never lost the social awkwardness he’d carried with him since his sudden rise to fame; he once joked that ‘The Ugly Duckling’ was the story of his life, but in reality he never quite learned to fit in.

Andersen never married, though not for want of trying. He fell hopelessly, unrequitedly in love with a string of unattainable women as well as men. His ill-at-ease social presence bemused and frustrated his friends, not least Charles Dickens, whom Andersen riled in 1857 with a seemingly endless visit; five weeks after his arrival at the Dickens family home, he had to be asked to leave. ‘He was a bony bore,’ Dickens’ daughter reported, ‘and he stayed on and on.’ In the ten years since their first meeting, Dickens had used a thinly veiled caricature of Andersen in David Copperfield: the ‘high-shouldered and bony’ clerk Uriah Heep.

Nevertheless, the quality of Andersen’s imagination and writing made him a national treasure and an international celebrity. In 1875, the year of his death, one London newspaper declared that his fairy tales ‘deserve a place in the pantheon where Homer and Shakespeare live forever’.

Andersen died in August 1875 at Rolighed (‘Calmness’), the home of a close friend. His funeral drew a large and eclectic crowd, from the king and crown prince down to representatives of the Workers’ Association for whom he had performed numerous readings. Since 1967 his birthday, 2 April, has been celebrated as International Children’s Book Day, although Andersen maintained to the end that his stories were written for everyone. ‘My fairy tales were just as much for adults as for children, who only understood the ornamental trappings,’ he wrote in his diary shortly before his death, ‘but only as mature adults can they see and perceive the contents. The naive was only one part of my fairy tales; the humour was the actual zest in them.’

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

History of Collins

Life & Times

The Tinder-box

The Elf of the Rose

The Emperor’s New Suit

The Fir Tree

The Ice Maiden

The Little Elder-tree Mother

The Little Match-seller

The Little Mermaid

Little Tiny or Thumbelina

The Princess and the Pea

The Money-box

The Nightingale

The Red Shoes

The Snail and the Rose-tree

The Shadow

The Shepherdess and the Sheep

The Snow Queen

The Brave Tin Soldier

The Travelling Companion

The Ugly Duckling

The Wild Swans

CLASSIC LITERATURE: WORDS AND PHRASES adapted from the Collins English Dictionary

About the Publisher

The Tinder-box

A soldier came marching along the high road: “Left, right—left, right.” He had his knapsack on his back, and a sword at his side; he had been to the wars, and was now returning home.

As he walked on, he met a very frightful-looking old witch in the road. Her under-lip hung quite down on her breast, and she stopped and said, “Good evening, soldier; you have a very fine sword, and a large knapsack, and you are a real soldier; so you shall have as much money as ever you like.”

“Thank you, old witch,” said the soldier.

“Do you see that large tree,” said the witch, pointing to a tree which stood beside them. “Well, it is quite hollow inside, and you must climb to the top, when you will see a hole, through which you can let yourself down into the tree to a great depth. I will tie a rope round your body, so that I can pull you up again when you call out to me.”

“But what am I to do, down there in the tree?” asked the soldier.

“Get money,” she replied; “for you must know that when you reach the ground under the tree, you will find yourself in a large hall, lighted up by three hundred lamps; you will then see three doors, which can be easily opened, for the keys are in all the locks. On entering the first of the chambers, to which these doors lead, you will see a large chest, standing in the middle of the floor, and upon it a dog seated, with a pair of eyes as large as teacups. But you need not be at all afraid of him; I will give you my blue checked apron, which you must spread upon the floor, and then boldly seize hold of the dog, and place him upon it. You can then open the chest, and take from it as many pence as you please, they are only copper pence; but if you would rather have silver money, you must go into the second chamber. Here you will find another dog, with eyes as big as mill-wheels; but do not let that trouble you. Place him upon my apron, and then take what money you please. If, however, you like gold best, enter the third chamber, where there is another chest full of it. The dog who sits on this chest is very dreadful; his eyes are as big as a tower, but do not mind him. If he also is placed upon my apron, he cannot hurt you, and you may take from the chest what gold you will.”

“This is not a bad story,” said the soldier; “but what am I to give you, you old witch? for, of course, you do not mean to tell me all this for nothing.”

“No,” said the witch; “but I do not ask for a single penny. Only promise to bring me an old tinder-box, which my grandmother left behind the last time she went down there.”

“Very well; I promise. Now tie the rope round my body.”

“Here it is,” replied the witch; “and here is my blue checked apron.”

As soon as the rope was tied, the soldier climbed up the tree, and let himself down through the hollow to the ground beneath; and here he found, as the witch had told him, a large hall, in which many hundred lamps were all burning. Then he opened the first door. “Ah!” there sat the dog, with the eyes as large as teacups, staring at him.

“You’re a pretty fellow,” said the soldier, seizing him, and placing him on the witch’s apron, while he filled his pockets from the chest with as many pieces as they would hold. Then he closed the lid, seated the dog upon it again, and walked into another chamber, And, sure enough, there sat the dog with eyes as big as mill-wheels.

“You had better not look at me in that way,” said the soldier; “you will make your eyes water;” and then he seated him also upon the apron, and opened the chest. But when he saw what a quantity of silver money it contained, he very quickly threw away all the coppers he had taken, and filled his pockets and his knapsack with nothing but silver.

Then he went into the third room, and there the dog was really hideous; his eyes were, truly, as big as towers, and they turned round and round in his head like wheels.

“Good morning,” said the soldier, touching his cap, for he had never seen such a dog in his life. But after looking at him more closely, he thought he had been civil enough, so he placed him on the floor, and opened the chest. Good gracious, what a quantity of gold there was! enough to buy all the sugar-sticks of the sweet-stuff women; all the tin soldiers, whips, and rocking-horses in the world, or even the whole town itself. There was, indeed, an immense quantity. So the soldier now threw away all the silver money he had taken, and filled his pockets and his knapsack with gold instead; and not only his pockets and his knapsack, but even his cap and boots, so that he could scarcely walk.

He was really rich now; so he replaced the dog on the chest, closed the door, and called up through the tree, “Now pull me out, you old witch.”

“Have you got the tinder-box?” asked the witch.

“No; I declare I quite forgot it.” So he went back and fetched the tinderbox, and then the witch drew him up out of the tree, and he stood again in the high road, with his pockets, his knapsack, his cap, and his boots full of gold.

“What are you going to do with the tinder-box?” asked the soldier.

“That is nothing to you,” replied the witch; “you have the money, now give me the tinder-box.”

“I tell you what,” said the soldier, “if you don’t tell me what you are going to do with it, I will draw my sword and cut off your head.”

“No,” said the witch.

The soldier immediately cut off her head, and there she lay on the ground. Then he tied up all his money in her apron, and slung it on his back like a bundle, put the tinderbox in his pocket, and walked off to the nearest town. It was a very nice town, and he put up at the best inn, and ordered a dinner of all his favourite dishes, for now he was rich and had plenty of money.

The servant, who cleaned his boots, thought they certainly were a shabby pair to be worn by such a rich gentleman, for he had not yet bought any new ones. The next day, however, he procured some good clothes and proper boots, so that our soldier soon became known as a fine gentleman, and the people visited him, and told him all the wonders that were to be seen in the town, and of the king’s beautiful daughter, the princess.

“Where can I see her?” asked the soldier.

“She is not to be seen at all,” they said; “she lives in a large copper castle, surrounded by walls and towers. No one but the king himself can pass in or out, for there has been a prophecy that she will marry a common soldier, and the king cannot bear to think of such a marriage.”

“I should like very much to see her,” thought the soldier; but he could not obtain permission to do so. However, he passed a very pleasant time; went to the theatre, drove in the king’s garden, and gave a great deal of money to the poor, which was very good of him; he remembered what it had been in olden times to be without a shilling. Now he was rich, had fine clothes, and many friends, who all declared he was a fine fellow and a real gentleman, and all this gratified him exceedingly. But his money would not last forever; and as he spent and gave away a great deal daily, and received none, he found himself at last with only two shillings left. So he was obliged to leave his elegant rooms, and live in a little garret under the roof, where he had to clean his own boots, and even mend them with a large needle. None of his friends came to see him, there were too many stairs to mount up. One dark evening, he had not even a penny to buy a candle; then all at once he remembered that there was a piece of candle stuck in the tinder-box, which he had brought from the old tree, into which the witch had helped him.

He found the tinder-box, but no sooner had he struck a few sparks from the flint and steel, than the door flew open and the dog with eyes as big as teacups, whom he had seen while down in the tree, stood before him, and said, “What orders, master?”

“Hallo,” said the soldier; “well this is a pleasant tinderbox, if it brings me all I wish for.

“Bring me some money,” said he to the dog.

He was gone in a moment, and presently returned, carrying a large bag of coppers in his month. The soldier very soon discovered after this the value of the tinder-box. If he struck the flint once, the dog who sat on the chest of copper money made his appearance; if twice, the dog came from the chest of silver; and if three times, the dog with eyes like towers, who watched over the gold. The soldier had now plenty of money; he returned to his elegant rooms, and reappeared in his fine clothes, so that his friends knew him again directly, and made as much of him as before.

After a while he began to think it was very strange that no one could get a look at the princess. “Every one says she is very beautiful,” thought he to himself; “but what is the use of that if she is to be shut up in a copper castle surrounded by so many towers. Can I by any means get to see her? Stop! where is my tinder-box?” Then he struck a light, and in a moment the dog, with eyes as big as teacups, stood before him.

“It is midnight,” said the soldier, “yet I should very much like to see the princess, if only for a moment.”

The dog disappeared instantly, and before the soldier could even look round, he returned with the princess. She was lying on the dog’s back asleep, and looked so lovely, that every one who saw her would know she was a real princess. The soldier could not help kissing her, true soldier as he was. Then the dog ran back with the princess; but in the morning, while at breakfast with the king and queen, she told them what a singular dream she had had during the night, of a dog and a soldier, that she had ridden on the dog’s back, and been kissed by the soldier.

“That is a very pretty story, indeed,” said the queen. So the next night one of the old ladies of the court was set to watch by the princess’s bed, to discover whether it really was a dream, or what else it might be.

The soldier longed very much to see the princess once more, so he sent for the dog again in the night to fetch her, and to run with her as fast as ever he could. But the old lady put on water boots, and ran after him as quickly as he did, and found that he carried the princess into a large house. She thought it would help her to remember the place if she made a large cross on the door with a piece of chalk. Then she went home to bed, and the dog presently returned with the princess. But when he saw that a cross had been made on the door of the house, where the soldier lived, he took another piece of chalk and made crosses on all the doors in the town, so that the lady-in-waiting might not be able to find out the right door.