Полная версия

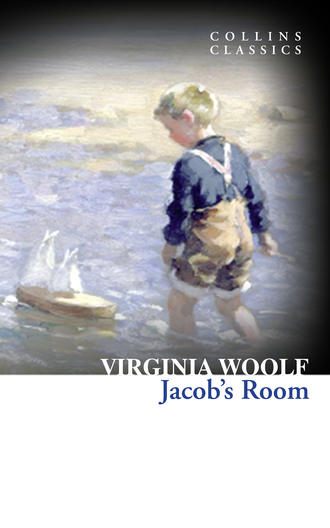

Jacob’s Room

JACOB’S ROOM

Virginia Woolf

History of Collins

In 1819, millworker William Collins from Glasgow, Scotland, set up a company for printing and publishing pamphlets, sermons, hymn books and prayer books. That company was Collins and was to mark the birth of HarperCollins Publishers as we know it today. The long tradition of Collins dictionary publishing can be traced back to the first dictionary William published in 1824, Greek and English Lexicon. Indeed, from 1840 onwards, he began to produce illustrated dictionaries and even obtained a licence to print and publish the Bible.

Soon after, William published the first Collins novel, Ready Reckoner; however, it was the time of the Long Depression, where harvests were poor, prices were high, potato crops had failed and violence was erupting in Europe. As a result, many factories across the country were forced to close down and William chose to retire in 1846, partly due to the hardships he was facing.

Aged 30, William’s son, William II took over the business. A keen humanitarian with a warm heart and a generous spirit, William II was truly ‘Victorian’ in his outlook. He introduced new, up-to-date steam presses and published affordable editions of Shakespeare’s works and The Pilgrim’s Progress, making them available to the masses for the first time. A new demand for educational books meant that success came with the publication of travel books, scientific books, encyclopaedias and dictionaries. This demand to be educated led to the later publication of atlases and Collins also held the monopoly on scripture writing at the time.

In the 1860s Collins began to expand and diversify and the idea of ‘books for the millions’ was developed. Affordable editions of classical literature were published and in 1903 Collins introduced 10 titles in their Collins Handy Illustrated Pocket Novels. These proved so popular that a few years later this had increased to an output of 50 volumes, selling nearly half a million in their year of publication. In the same year, The Everyman’s Library was also instituted, with the idea of publishing an affordable library of the most important classical works, biographies, religious and philosophical treatments, plays, poems, travel and adventure. This series eclipsed all competition at the time and the introduction of paperback books in the 1950s helped to open that market and marked a high point in the industry.

HarperCollins is and has always been a champion of the classics and the current Collins Classics series follows in this tradition – publishing classical literature that is affordable and available to all. Beautifully packaged, highly collectible and intended to be reread and enjoyed at every opportunity.

Life & Times

Mental Health and Creativity

It would be fair to say that Virginia Woolf was an intense and complex personality. Some might describe her as highly imaginative, sensitive and creative, while others might use the words high-maintenance, introspective and obsessive. In truth, she was all of the above, which meant that she was highly regarded as a novelist by many and entirely disregarded by others.

The central sticking point with the latter was that she came from a highly privileged, upper-middle-class background, yet she viewed the world in quite a negative light. Untroubled by the daily pressures of most, her time was spent in deep analysis of life – or rather, her own life and that of her friends and family. Her literature, therefore, could occasionally disconnect with the lay reader, because her concerns could be seen as self-indulgent and focused on a rarified environment to which most people were not privy.

As a human specimen, Woolf was not a very robust figure. She was prone to bouts of depression and breakdown, in part possibly brought on by the lack of any necessity to just get on with activities that were positive for her mental and physical constitution. In the absence of responsibilities to toughen the character, she lived in a world of ever-decreasing circles until, one day, her horizons closed in so tight that she chose suicide as a means of escape. She filled the pockets of her overcoat with pebbles and walked headlong into a river to drown her sorrows, quite literally. Her life was ended by her own thoughts and actions at the age of 59.

Woolf is a classic case of an artist whose creative expression was bad for their health. Had she abandoned writing in favour of an occupation that took her mind away from her obsessive thoughts, she would undoubtedly have lived a happier and more fulfilled life, but instead she became the author of her own undoing. So, a weighty question remains: was it worth all the pain and suffering? Inevitably those with similar leanings will say yes, because they are able to identify with Woolf’s desire to commit her thoughts to the written word as a kind of catharsis. Inevitably those who cannot identify will say no, because her work offers nothing to which they can relate as they have no need of therapy. It may be that there has never been a more divisive novelist in the history of English literature, and this is probably Woolf’s most interesting aspect.

Woolf’s main influence on modern literature was her ‘stream of consciousness’ approach to prose. Her novels were really vehicles for the copious current of thoughts and emotions to flow without parameters. She was an aesthete and intelligentsium, investing all of her mental capacity into understanding and disseminating the minutiae of human nature, human society, human culture and the human condition. Woolf and her set could be seen as looking down on those who chose not to analyse human existence in such microscopic detail, but realistically this was probably the result of insecurities about one’s own talent, context and significance. The one thing that is certain about belief systems is that believing things doesn’t make them true. This is certainly not to say that Woolf’s portfolio has no value – far from it – but that we do well to remember the context of the author. After all, it was precisely because she existed in her particular milieu that she produced her pioneering style of literature. Moreover, had she been born into a more typical, lower-middle or working class background, she would probably not have had the wherewithal to dissect humanity to such a level.

The Bloomsbury Set

Virginia Woolf came from a background of intellectualism; however, this was largely cemented by her family’s relocation from Kensington to Bloomsbury, where she became part of an intellectual elite known as the Bloomsbury Set. Together, they were all goldfish in the same bowl, looking out at the world around them with a similar artistic palette.

The pretentions of her social group actually allowed her to blossom as a writer, because she was given the encouragement and freedom she needed to experiment with her prose. In short, she was allowed to think of herself as an author and she was told what she wanted to hear. This was vitally important to someone with nagging self-doubt, so she developed deep and lasting bonds with those who saw and nurtured her potential. Indeed, she married one of them – Leonard Woolf – and remained devoted to him.

In time, of course, the pretentions of the Bloomsbury Set transcended into success, as they were undoubtedly intelligent, talented and well educated. This process of ascendance was, in part, aided by a number of stunts designed to draw public attention. One stunt in particular has become famous for its daring and humour: the Dreadnought Hoax. This was an elaborate plan to gain egress to the battleship HMS Dreadnought for no other reason than to have a good look around. A number of the Bloomsbury Set, including Woolf, disguised themselves as Abyssinian princes. They wore the appropriate garb of robes and turbans, but they also ‘blacked-up’ and sported fake beards. With escort and interpreter in tow, they boarded a VIP coach and took a train from Paddington to Weymouth, where they were received as genuine royalty with honour guard and allowed to inspect the Royal Navy fleet. All the while, they pretended to communicate in a foreign tongue by uttering gibberish furnished with Greek and Latin, which the interpreter duly pretended to understand and translate.

Having returned to London, a photograph of the Bloomsbury Set, still in character, was sent to the Daily Mirror newspaper and the hoax was revealed. Not surprisingly, the affair turned into a scandal. The Foreign Office and the Royal Navy were the target of a great deal of finger-pointing, partly in fun and partly in seriousness for allowing such a blatant lapse in national security. The situation wasn’t helped by the fact that the Bloomsbury Set were pacifists, which only served to rub salt into the wound. When the Navy high command pushed to have the perpetrators punished, they found themselves powerless to do anything. For one thing, no laws were broken, and secondly the consensus was that they themselves should be punished for allowing themselves to be beguiled by such a lame practical joke.

Needless to say, the Dreadnought Hoax planted the Bloomsbury Set in the public consciousness once and for all, as the oxygen of publicity was theirs to breathe in and enjoy. The hoax occurred on 7 February, 1910. Woolf’s first novel was begun the same year, although she did not publish until 1915, by which time she was already a minor celebrity.

Despite her subsequent success, Woolf was never particularly contented, however, for she had such a troubled soul and indefatigable mind. Today her malady would, doubtless, be described as a bipolar condition, for she oscillated from exuberant mood highs to despairing clinical lows. In the end, she was convinced that she would never come full circle again, so she decided to cut her loses while in the grip of a crushing depression that rendered her unable to see any light at the end of the tunnel. Virginia Woolf died in 1941, leaving behind a highly respected, progressive and considerable canon of essays, critique and novels.

Jacob’s Room

Jacob’s Room (1922) is an intriguing literary experiment by Woolf. She constructs a character by primarily piecing together the memories of others – notably, all of them female. Thus, the eponymous Jacob is never met directly by the reader. He is a fragmentary assemblage of information, which is ambiguous because the sources of information are subjective. Just as history is always an interpretation of past events, rather than the absolute truth, so Jacob’s personality is an interpretation, too.

From a literary point of view, Jacob’s Room is a vitally important contribution to the evolution of the novel. The plot is largely inconsequential to the book, because Woolf’s objective is based on wondering how we might get to know someone on the basis of circumstantial evidence. In effect, she plays a similar role to a police investigator building the profile of a dead or missing person. This makes for an intriguing concept, as it prompts the reader to wonder just how their own personality might be represented and assembled through other people’s reports and remnants of information. The abiding existential enquiry is whether anyone can be described accurately and truthfully. It makes us realise that most of what we are is hidden below the surface anyway, and what we reveal are only considered glimpses of the real complexity of our psychology. As a result, others have different perspectives on our characters, and we ourselves have a different perspective, based largely on how we would like to be viewed rather than how we are likely to be viewed.

Woolf’s work was a seminal event, because it opened the way for experimental forms of literature. Just as avant-garde painters and sculptors were finding new ways to utilise their media, so Woolf was doing similar things with her prose. We might think of Jacob’s Room as a form of artistic abstraction, leaving the reader to do some of the work just as they are expected to do so in a modern art gallery. Woolf had the mind of a progressive artist, wishing to do something new for the sake of pushing the boundaries and making the novel worthy of exploration as a genre, both for her and for the reader.

Of course, it doesn’t necessarily mean that groundbreaking creativity is always accessible or enjoyable. To appreciate frontline art, of any kind, it generally requires a combination of open-mindedness and an education in the movement concerned, which is why so many artists and writers often fail in this regard. In their defence, however, successful experimentation often requires the omission of familiar elements. In this case, plot and allegory are largely neglected to allow the author to focus on the experiment. As a result the story is imbued with a feeling of uncomfortable emptiness due to the constant absence of Jacob. Additionally, there is a very poignant ending, making it clear that Woolf was inspired by a theme familiar to many in the early 1920s: coming to terms with the loss of millions of men following the Great War. Unfortunately all of these lost men, too, became assemblages of memories.

Table of Contents

Title Page

History of Collins

Life & Times

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases adapted from the Collins English Dictionary

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

“So of course,” wrote Betty Flanders, pressing her heels rather deeper in the sand, “there was nothing for it but to leave.”

Slowly welling from the point of her gold nib, pale blue ink dissolved the full stop; for there her pen stuck; her eyes fixed, and tears slowly filled them. The entire bay quivered; the lighthouse wobbled; and she had the illusion that the mast of Mr. Connor’s little yacht was bending like a wax candle in the sun. She winked quickly. Accidents were awful things. She winked again. The mast was straight; the waves were regular; the lighthouse was upright; but the blot had spread.

“… nothing for it but to leave,” she read.

“Well, if Jacob doesn’t want to play” (the shadow of Archer, her eldest son, fell across the notepaper and looked blue on the sand, and she felt chilly—it was the third of September already), “if Jacob doesn’t want to play”—what a horrid blot! It must be getting late.

“Where IS that tiresome little boy?” she said. “I don’t see him. Run and find him. Tell him to come at once.” “… but mercifully,” she scribbled, ignoring the full stop, “everything seems satisfactorily arranged, packed though we are like herrings in a barrel, and forced to stand the perambulator which the landlady quite naturally won’t allow. …”

Such were Betty Flanders’s letters to Captain Barfoot—many-paged, tear-stained. Scarborough is seven hundred miles from Cornwall: Captain Barfoot is in Scarborough: Seabrook is dead. Tears made all the dahlias in her garden undulate in red waves and flashed the glass house in her eyes, and spangled the kitchen with bright knives, and made Mrs. Jarvis, the rector’s wife, think at church, while the hymn-tune played and Mrs. Flanders bent low over her little boys’ heads, that marriage is a fortress and widows stray solitary in the open fields, picking up stones, gleaning a few golden straws, lonely, unprotected, poor creatures. Mrs. Flanders had been a widow for these two years.

“Ja—cob! Ja—cob!” Archer shouted.

“Scarborough,” Mrs. Flanders wrote on the envelope, and dashed a bold line beneath; it was her native town; the hub of the universe. But a stamp? She ferreted in her bag; then held it up mouth downwards; then fumbled in her lap, all so vigorously that Charles Steele in the Panama hat suspended his paint-brush.

Like the antennae of some irritable insect it positively trembled. Here was that woman moving—actually going to get up—confound her! He struck the canvas a hasty violet-black dab. For the landscape needed it. It was too pale—greys flowing into lavenders, and one star or a white gull suspended just so—too pale as usual. The critics would say it was too pale, for he was an unknown man exhibiting obscurely, a favourite with his landladies’ children, wearing a cross on his watch chain, and much gratified if his landladies liked his pictures—which they often did.

“Ja—cob! Ja—cob!” Archer shouted.

Exasperated by the noise, yet loving children, Steele picked nervously at the dark little coils on his palette.

“I saw your brother—I saw your brother,” he said, nodding his head, as Archer lagged past him, trailing his spade, and scowling at the old gentleman in spectacles.

“Over there—by the rock,” Steele muttered, with his brush between his teeth, squeezing out raw sienna, and keeping his eyes fixed on Betty Flanders’s back.

“Ja—cob! Ja—cob!” shouted Archer, lagging on after a second.

The voice had an extraordinary sadness. Pure from all body, pure from all passion, going out into the world, solitary, unanswered, breaking against rocks—so it sounded.

Steele frowned; but was pleased by the effect of the black—it was just THAT note which brought the rest together. “Ah, one may learn to paint at fifty! There’s Titian …” and so, having found the right tint, up he looked and saw to his horror a cloud over the bay.

Mrs. Flanders rose, slapped her coat this side and that to get the sand off, and picked up her black parasol.

The rock was one of those tremendously solid brown, or rather black, rocks which emerge from the sand like something primitive. Rough with crinkled limpet shells and sparsely strewn with locks of dry seaweed, a small boy has to stretch his legs far apart, and indeed to feel rather heroic, before he gets to the top.

But there, on the very top, is a hollow full of water, with a sandy bottom; with a blob of jelly stuck to the side, and some mussels. A fish darts across. The fringe of yellow-brown seaweed flutters, and out pushes an opal-shelled crab—

“Oh, a huge crab,” Jacob murmured—and begins his journey on weakly legs on the sandy bottom. Now! Jacob plunged his hand. The crab was cool and very light. But the water was thick with sand, and so, scrambling down, Jacob was about to jump, holding his bucket in front of him, when he saw, stretched entirely rigid, side by side, their faces very red, an enormous man and woman.

An enormous man and woman (it was early-closing day) were stretched motionless, with their heads on pocket-handkerchiefs, side by side, within a few feet of the sea, while two or three gulls gracefully skirted the incoming waves, and settled near their boots.

The large red faces lying on the bandanna handkerchiefs stared up at Jacob. Jacob stared down at them. Holding his bucket very carefully, Jacob then jumped deliberately and trotted away very nonchalantly at first, but faster and faster as the waves came creaming up to him and he had to swerve to avoid them, and the gulls rose in front of him and floated out and settled again a little farther on. A large black woman was sitting on the sand. He ran towards her.

“Nanny! Nanny!” he cried, sobbing the words out on the crest of each gasping breath.

The waves came round her. She was a rock. She was covered with the seaweed which pops when it is pressed. He was lost.

There he stood. His face composed itself. He was about to roar when, lying among the black sticks and straw under the cliff, he saw a whole skull—perhaps a cow’s skull, a skull, perhaps, with the teeth in it. Sobbing, but absent-mindedly, he ran farther and farther away until he held the skull in his arms.

“There he is!” cried Mrs. Flanders, coming round the rock and covering the whole space of the beach in a few seconds. “What has he got hold of? Put it down, Jacob! Drop it this moment! Something horrid, I know. Why didn’t you stay with us? Naughty little boy! Now put it down. Now come along both of you,” and she swept round, holding Archer by one hand and fumbling for Jacob’s arm with the other. But he ducked down and picked up the sheep’s jaw, which was loose.

Swinging her bag, clutching her parasol, holding Archer’s hand, and telling the story of the gunpowder explosion in which poor Mr. Curnow had lost his eye, Mrs. Flanders hurried up the steep lane, aware all the time in the depths of her mind of some buried discomfort.

There on the sand not far from the lovers lay the old sheep’s skull without its jaw. Clean, white, wind-swept, sand-rubbed, a more unpolluted piece of bone existed nowhere on the coast of Cornwall. The sea holly would grow through the eye-sockets; it would turn to powder, or some golfer, hitting his ball one fine day, would disperse a little dust—No, but not in lodgings, thought Mrs. Flanders. It’s a great experiment coming so far with young children. There’s no man to help with the perambulator. And Jacob is such a handful; so obstinate already.

“Throw it away, dear, do,” she said, as they got into the road; but Jacob squirmed away from her; and the wind rising, she took out her bonnet-pin, looked at the sea, and stuck it in afresh. The wind was rising. The waves showed that uneasiness, like something alive, restive, expecting the whip, of waves before a storm. The fishing-boats were leaning to the water’s brim. A pale yellow light shot across the purple sea; and shut. The lighthouse was lit. “Come along,” said Betty Flanders. The sun blazed in their faces and gilded the great blackberries trembling out from the hedge which Archer tried to strip as they passed.

“Don’t lag, boys. You’ve got nothing to change into,” said Betty, pulling them along, and looking with uneasy emotion at the earth displayed so luridly, with sudden sparks of light from greenhouses in gardens, with a sort of yellow and black mutability, against this blazing sunset, this astonishing agitation and vitality of colour, which stirred Betty Flanders and made her think of responsibility and danger. She gripped Archer’s hand. On she plodded up the hill.

“What did I ask you to remember?” she said.

“I don’t know,” said Archer.

“Well, I don’t know either,” said Betty, humorously and simply, and who shall deny that this blankness of mind, when combined with profusion, mother wit, old wives’ tales, haphazard ways, moments of astonishing daring, humour, and sentimentality—who shall deny that in these respects every woman is nicer than any man?

Well, Betty Flanders, to begin with.

She had her hand upon the garden gate.

“The meat!” she exclaimed, striking the latch down.

She had forgotten the meat.

There was Rebecca at the window.

The bareness of Mrs. Pearce’s front room was fully displayed at ten o’clock at night when a powerful oil lamp stood on the middle of the table. The harsh light fell on the garden; cut straight across the lawn; lit up a child’s bucket and a purple aster and reached the hedge. Mrs. Flanders had left her sewing on the table. There were her large reels of white cotton and her steel spectacles; her needle-case; her brown wool wound round an old postcard. There were the bulrushes and the Strand magazines; and the linoleum sandy from the boys’ boots. A daddy-long-legs shot from corner to corner and hit the lamp globe. The wind blew straight dashes of rain across the window, which flashed silver as they passed through the light. A single leaf tapped hurriedly, persistently, upon the glass. There was a hurricane out at sea.