Полная версия

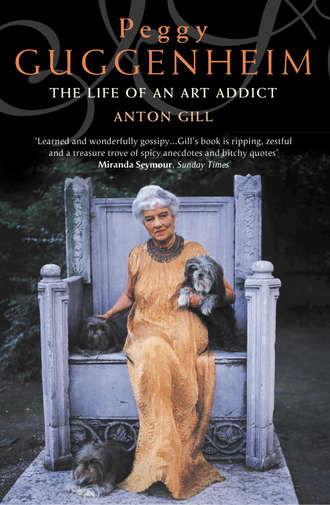

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

Suddenly Harold Loeb himself strode in vigorously, saw Duff, and stood stock-still; he had evidently heard she was in town and gone looking for her. He sat down at our table and said little, but looked his feelings much as Robert Cohn was described as doing. Duff’s English friend then made little signs of irritation at Harold’s presence (quite as in the novel). Laurence Vail ventured the remark: ‘Well now, all we need is to have Ernest drop in to make it a quorum.’

Laurence Vail was one of the people Peggy met and was fascinated by during the time she worked at the Sunwise Turn, and he was the one destined to have the most profound effect on her life; but at the time there were plenty of others: the poets Alfred Kreymborg and Lola Ridge were frequently there, as were the painters Marsden Hartley and Charles Burchfield, and, among the writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald. Peggy idolised Mary Mowbray Clarke, who became a role model for her as a liberated woman and a friend of artists.

Peggy, though she had no idea of how to mix with these new and intriguing people, and though she came to work swathed in scent, wearing pearls and ‘a magnificent taupe coat’, still had to work. And it wasn’t always fun. Her mother was suspicious of the bookshop and constantly popped in to check up on her daughter, embarrassing her by bringing her a raincoat if the weather turned bad, and irritating her with her questions. Equally embarrassing, though welcome to the bookshop (which throws a sidelight on Clarke), was a succession of Guggenheim and Seligman aunts who ordered books by the yard to fill up the shelves of their apartments and houses. These books were never intended to be read: they were a kind of wallpaper.

The work itself was mainly dull, routine filing, but Peggy did it willingly, for the joy of being in such a place more than compensated for the grind. One thing she did resent, however, was that she was only allowed down into the shop itself, from the gallery where her desk was, at lunchtimes, and even then she was only allowed to sell books if no one else was on hand. Whether Clarke considered her too much of a greenhorn or too much of a liability if let loose on the floor of the shop is unclear.

However, Peggy did gradually get to meet the people she wanted to meet, and she softened any reservations Clarke had by being not only a good employee but a good customer. In lieu of a wage, she was allowed a 10 per cent discount on any book she bought. To give herself the impression of getting a good salary, she bought modern literature in stacks and read it all with her usual voraciousness.

Among the other luminaries who frequented the Sunwise Turn were Leon and Helen Fleischman. Leon was a director of the publishers Boni and Liveright, and Helen, who like Peggy came from a leading New York Jewish family, had embraced the bohemian life. Following one of the fashions which succeeded the social upheaval marked by the end of the First World War, Leon and Helen played at having an open marriage. Peggy, who latched on to them as substitutes for Benita, whom she still missed bitterly, promptly fell for Leon. In a passage omitted from the bowdlerised 1960 edition of her autobiography, she tells us: ‘I fell in love with Leon, who to me looked like a Greek God, but Helen didn’t mind. They were so free.’ We do not learn whether or not the crush led to any kind of affair. Peggy then was more interested in settling into and being accepted by an artistic milieu.

The Fleischmans introduced Peggy to Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz, then in his mid-fifties, was a pioneer of photography and the founder of the avant-garde Photo-Secession group. Leon and Helen took Peggy to meet him at 291, his tiny gallery on 5th Avenue. How formative the meeting was at the time for Peggy we do not know, but Stieglitz, whose interests were not confined to photography, was the first to show Cézanne, Picasso and Matisse in the United States, and at the time of their meeting was increasingly interested in modern abstract art. The 291 Gallery became an important centre for avant-garde painting and sculpture, and on this occasion Peggy had her first experience of it. She was shown a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe, later Stieglitz’s wife. We are not told what the picture was, but it was clearly an abstract, because Peggy ‘turned it around four times before I decided which way to look at it’. Her response must have been positive, because the reaction of her friends and of Stieglitz was one of delight. Peggy further tells us that although didn’t see Stieglitz again for another twenty-five years, ‘when I talked to him I felt as if there had been no interval. We took up where we left off.’ By then, of course, Peggy had become a doyenne of modern art herself. But was seeing the O’Keeffe her epiphany? Or did abstract painting simply provide a focus for her rebellious spirit, symbolising as it did the unconventional and questioning psyche of her new friends, with whom she was beginning to feel more and more at home? It would still be a long time before her own association with modern art began, and as she was never a reflective person, it’s possible that epiphanies, whether conscious or unconscious, were not in her line.

What she wanted was to belong. What got in the way was her own inability to give.

Laurence Vail was also a friend of the Fleischmans. He was the son of an American mother and a Franco-American father, and although he was an American citizen, he had been brought up in France and educated at Oxford, where he read modern languages. Fluent in English, French and Italian – he served as a liaison officer in the US Army with the heavy artillery during the war – European in manner, speaking with an Anglo-French accent, he could be charming and debonair. He turned twenty-nine in 1920, but still had not found his way into any particular artistic field, though there was no doubt that it was in the arts that his talents lay, being both a passable painter and, which seemed to be his forte, a writer. Based in Paris, he was in New York because a short play of his, What D’You Want? was to be produced by the Provincetown Players, an innovative group with their roots in Provincetown, Massachusetts, but who by now were producing work at the Playwrights’ Theatre in Greenwich Village and at the Greenwich Village Theatre. Vail’s one-acter was to be performed as a curtain-raiser to a Eugene O’Neill play. In Vail’s cast was a woman who would later play a significant part in Peggy’s life, Mina Loy. Vail also had a bit-part in O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, already a Provincetown success, now playing in New York.

Greenwich Village had begun to fill with artistic life. Rents were low, and word spread. Perhaps the most striking single symbol of the new order in New York, though far from the most important, was a German, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She had drifted from an unhappy and poor home into prostitution, but later managed to enrol as an art student in Munich, whence she moved via a wretched marriage into German literary circles. A colourful lover brought her to America as he sought to escape the clutches of the police at home, but he abandoned her in Kentucky in 1909. The thirty-five-year-old Elsa made her way to New York, where she married the impoverished exiled German baron from whom she got her title. He left her at the outbreak of war and killed himself in Switzerland at its end. Remaining in New York, she drifted into modelling for artists, lived hand-to-mouth, was adopted as an occasional contributor and cause célèbre by the Little Review, and turned herself into the living embodiment of the age. To visit the French consul she wore an icing-sugar-coated birthday cake on her head, complete with fifty lit candles, with matchboxes or sugarplums for earrings. Her face was stuck with stamps as ‘beauty-spots’ and she had painted her face emerald green. Her eyelashes were gilded porcupine quills and she wore a necklace of dried figs. On another occasion she adopted yellow face-powder and black lipstick, setting the effect off with a coal-scuttle worn as a hat, and on yet another – and this was in 1917 – she met the writer and painter George Biddle dressed in a scarlet raincoat, which she swept open ‘with a royal gesture’ to reveal that she was all but naked underneath:

Over the nipples of her breasts were two tin tomato cans, fastened with a green string about her back. Between the tomato cans hung a very small birdcage and within it a crestfallen canary. One arm was covered from wrist to shoulder with celluloid curtain rings, which she later admitted to have pilfered from a furniture display in Wanamaker’s. She removed her hat, which had been tastefully but inconspicuously trimmed with gilded carrots, beets and other vegetables. Her hair was close cropped and dyed vermilion.

This true original could not last. Living as she did in squalor, and always in trouble with the police, her popularity faded with her looks, and her mind gradually crumbled. Abandoned by all but a few, one of them being the novelist Djuna Barnes, she made her way back to Europe, where she ended up in dire poverty in Potsdam. Her body was found shortly before Christmas 1927, her head resting in a gas oven. Peggy never knew her; but she heard of her, and was fascinated and scared of such a complete personification of non-conformity.

It wasn’t just in Greenwich Village that America was enjoying the sense of relief and the economic boom that followed the war. This revolution had started before the war, finding its greatest expression in the visual arts and in music. Modern art really was new then. In the time of the frock-coat and the hobble-skirt, of the horse-drawn carriage and the steam engine, Cubism was born and Stravinsky wrote The Firebird. There had never been an artistic revolution quite like it.

It was fired by the First World War, which speeded up similarly revolutionary technological progress, but Picasso and Braque were painting Cubist pictures well before 1914, and in Italy Balla and Severini were experimenting with arresting the visual impression of movement while motion photography was still in its infancy. The period either side of the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was one of frantic technological progress, yet in 1920 the bicycle was still one of the fastest modes of transport, air travel was unknown to all but a few, and cars, telephones and radios were rare. The telegraph had been developed further during the war, but was not yet in common use. The RMS Titanic was the first to transmit SOS distress signals as she sank. There was no television yet. Computers as we know them lay far in the future.

Peggy was born in the Victorian age. By 1920 she was in the jazz age; her life had been contemporaneous with the transition, and, having the will, she moved effortlessly with the times.

In the meantime, a party was in progress. In the few years following 1918, American women changed their wardrobe by 45 per cent: the sartorial revolution typified by the flapper showed how strong the desire was to get away from the pre-war atmosphere, with its restrictive morals, its nationalism, class-divisiveness and provincialism. When the conservative establishment tried to curb the new and alarming tendencies, most obviously in a fundamentally puritanical America by introducing the prohibition of alcohol nationwide in 1920, the result was an unprecedented crime wave and a record increase in the consumption of alcohol.

Nothing could stopper the bottle again. The genie had been let out. Peggy was a child of her time; and along with many young Americans, she didn’t just bob her hair, wear short skirts, and dance and drink – she left.

CHAPTER 6 Departure

Peggy, still living at home, began to feel that the boundaries of the Sunwise Turn were also too narrow. She liked Laurence Vail, responding to his European manner and finding him less daunting than most of the habitués of the bookshop. Now, to Florette’s great relief, her daughter announced her intention of giving up work. Instead, she wanted to travel. She had been to Europe frequently as a girl, but not yet as a woman. The idea seemed to Florette to chime more harmoniously with her idea of what Peggy should be doing. Florette was unaware of the influence Laurence’s acquaintance had had on her; though it is just as likely that Peggy’s decision to go abroad was based on her cousin Harold’s own imminent departure.

Greenwich Village had been an undiscovered country for Peggy, but her sympathies lay with those who lived there. Many young male artists had been hardened in the fire of the war, but everyone was enjoying the euphoria that followed it, and many were also enjoying the economic boom it had created. Men who had served either in the army or with the ambulance corps in Europe had had their first experience of the old world, and had liked what they saw.

There had been precursors. Henry James had left America for Europe in 1875, and Gertrude Stein settled in Paris in 1902. The painter Marsden Hartley had lived in Berlin before the First World War, and when his German lover, an infantry officer, was killed during it, his death inspired Hartley to carry out a moving series of paintings. To someone from provincial America, New York was stunning enough, and provided a kind of halfway house; but for the artist the attractions of such cities as Paris, Rome, Berlin and London were irresistible.

It was Paris that most of them had got to know, and it was to Paris that they wished to return. France quickly became the focus of artistic expression in Europe after the war – an expression which reflected both disenchantment with the established order which the war had called into question, and the joy of freedom which succeeded it. Paris was at its centre, and for young artists from America there was an added, practical dimension: in the 1920s one dollar bought twenty French francs, and though this dropped back to fourteen francs, there it stabilised. You could live easily and even well on five dollars a day in France, including hotels and travelling expenses. The cost of living in general was half that of the USA. Matthew Josephson reports that a litre of Anjou wine could be had for nine centimes, and a good meal for two would only cost between two and three francs; John Glassco and his friend Graeme Taylor stayed at the Hôtel Jules César in Paris for the equivalent of twenty dollars a month, and breakfast in bed only cost fifteen cents a day on top of that.

Peggy, with a private income of over $20,000 a year, could look forward to living as well as she pleased. But the money was a mixed blessing. Unlike the people with whom she sought to associate, she had no need to earn a living.

Three of Peggy’s close contemporaries with whom her life was to interact, the poet and designer Mina Loy and the writers Djuna Barnes and Kay Boyle, were all aware of nascent feminism, in the form of women’s suffrage and a consciousness that women artists should achieve the same recognition as men. In 1913, as an eleven-year-old, Boyle had been taken by her ambitious and artistic mother to the Armory Show in New York, an influential exhibition staged by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, of which Alfred Stieglitz was honorary vice-president, that put on show more than 1100 international modern works of art. Peggy, rising fifteen at the time, did not have the advantage of such a parent, and was scarcely feeling her way towards an artistic sensibility then. The somewhat older Mina Loy (she was born in London in 1882) was living in Florence when the Armory Show was on, but her friend, the iconoclastic Mabel Dodge, was closely involved in its inception. Mina, furthermore, had already spent some time, in 1900, at the Künstlerinnenverein in Munich, the academy for women artists founded in the year of her birth.

The real point here is that all these women had an early association with the artistic world, wanted to join it as active artists, and had to work for a living. Barnes never married, but Boyle and Loy did and, like Peggy, were poor mothers. Had they been born in a later age it is open to question whether they would have had families at all. They were essentially independent spirits, and they would not be fobbed off with the ‘image’ of emancipated womanhood portrayed in the drawings of Charles Dana Gibson. The Gibson girl may have been self-assured and vivacious, but she was still an idea of women as men would like them to be. She had none of the muscle of the suffragette. Women had a long struggle ahead of them, and it would take at least another sixty years before they even began to enjoy some truly equal rights, in the Western world at least. In artistic circles as elsewhere, men held sway, and male artists were more often than not sexual chauvinists. Peggy has been presented as a proto-feminist. She was never anything of the sort. But she did make her presence felt, and asserted her independence.

But not yet. Nor was she as free of her mother as she would have liked to be, or cared to admit. When she started her preparations for departure to Paris, her plans included Florette and a cousin of Peggy’s Aunt Irene, Valerie Dreyfus, as travelling companions. Nor of course were they destined for the Left Bank.

2 Europe

‘Soon after, I went to Europe. I didn’t realise at the time that I was going to remain there for twenty-one years but that wouldn’t have stopped me … In those days, my desire for seeing everything was very much in contrast to my lack of feeling for anything.’

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM, Out of this Century

CHAPTER 7 Paris

The first trip was a toe-in-the-water affair – Peggy isn’t being entirely truthful when she says she didn’t return to the United States for twenty-one years. What is more important is that, whether the encounter with the Georgia O’Keeffe abstract kindled an interest in modern art or not, a desire to know more about painting was growing within Peggy by now.

She sailed with her mother and Valerie to Liverpool. From there they visited the Lake District, then took a tour of Scotland, and meandered through England before crossing to France and ‘doing’ the châteaux of the Loire. By the time they arrived in Paris Florette was exhausted and only too happy to settle down in the Crillon, then as now one of the most expensive and most agreeable hotels in Paris, and a far cry from the Left Bank as it was then. Peggy had quickly developed a passion for travel and the new experiences it brought. Valerie, already an experienced traveller, shared her enthusiasm, and guided her through Belgium and Holland, and afterwards Italy and Spain. In 1920–21, they were in the vanguard: Europe lay before them unspoilt and unexplored.

Above all, their exploration was centred on art. Just as she had felt at home among the people who had frequented the Sunwise Turn, now Peggy felt at home in Europe, the land of her grandparents, which she had liked as a child, and after four years’ separation because of the war, now found that as an adult she adored. ‘I soon knew where every painting in Europe could be found, and I managed to get there, even if I had to spend hours going to a little country town to see only one.’

Valerie may have been a valuable cicerone, but as far as art was concerned another figure was more significant. He was Armand Lowengard, the nephew of Sir Joseph Duveen. (Duveen, later elevated to the peerage, was a noted art dealer and a friend of the English branch of the Seligman family. His name is commemorated in the Duveen Galleries at the British Museum, his gift to that institution, which house the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon.) Armand was a great aficionado of Renaissance Italian painting, but when they met in France, he told Peggy that she would never be able to understand the work of the art historian Bernhard Berenson. This fired her up: ‘I immediately bought and digested seven volumes of that great critic.’ She read about what to look for in a painting – tactile values, space-composition, movement and colour – absorbed her lessons and tried to apply them. Later in life she met the great man himself, who was horrified by modern art (though he noted a tapestry-like quality in the work of Jackson Pollock), and was able gently to tease him.

No doubt Peggy was sincere in her desire to learn, but she was also no slouch when it came to self-aggrandisement. From the well-used library she left at her death, one can see that she’d read all the great art historians and critics of her day, but along with her interest in paintings, she was becoming equally interested in sex. She was certainly too much for Armand: ‘My vitality nearly killed him and though he was fascinated by me, in the end he had to renounce me, as I was entirely too much for him.’

In Paris there were other diversions and at least one other boyfriend. Peggy mentions a boy called Pierre who was ‘a sort of cousin of my mother’s’. Whoever he was, she boasts that she kissed him on the same day as she kissed Armand, and displays a naïve guilt at being so daring. There were the fashion houses to explore and enjoy with a Russian girlfriend she had made, Fira Benenson. Peggy took Russian lessons so that Fira could have no secrets from her, but did not get very far. They visited Lanvin, Molyneux and Poiret, dressed to kill and vied with each other in collecting proposals of marriage. But they had a good, conventional, rich-girl time at the Crillon, under the protective eye of Florette. As far as Peggy’s interest in art was concerned, there was no problem. Uncle Solomon’s wife, Aunt Irene (Valerie’s cousin), was a collector of Old Masters and had a good eye.

This pleasant idyll, which lasted the better part of nine months, was interrupted by a brief return home to attend the wedding of Peggy’s younger sister Hazel. Hazel was marrying within ‘the Crowd’: Sigmund M. Kempner was a respectable graduate of Harvard, and Florette was probably relieved to see her maverick youngest daughter safely wed. Peggy remained a bit of a wild card, but with luck she would soon follow her sisters’ examples. Meanwhile, Benita was failing to produce an heir, and, given her delicate constitution, that was a worry.

Hazel’s wedding took place at the Ritz-Carlton in New York at the beginning of June 1921. The marriage lasted a year, and for her it was the first of seven. For the moment, though, Florette was content.

Back in New York, Peggy renewed some old acquaintances, among them the Fleischmans. Leon had by now resigned from Boni and Liveright, and the couple had produced a baby. They had little money and no clear idea of what to do next, so when Peggy suggested that they join her when she returned to Paris, they accepted her invitation gladly.

Peggy couldn’t wait to get back. In Europe, and especially in Paris, she had encountered none of the stuffiness and none of the anti-Semitism she associated with home. It is true that she hadn’t entered the vie bohème at all, but the Fleischmans would be more stimulating companions than her mother or even her second cousin. However, Florette and Valerie were not left behind when Peggy returned to Paris, and the only immediate change was of hotel – instead of the Crillon, they stayed at the Plaza-Athénée.

Paris itself was changing fast. Americans of Peggy’s generation were forming colonies in Montparnasse, where the rents were low, and around what was then the Hôtel Jacob in the rue Jacob just north of the boulevard St Germain, but as we’ve seen, arrivals in 1921 were still in the vanguard. US land forces had only taken an active part in the fighting for the last four or five months of the war. The traumatic losses sustained by the British, French and Germans over four years had not been experienced by the Americans, who came to the Old World fresher, richer and more innocent than the people they discovered there. In return for their curiosity they learned to be more cosmopolitan, to shed prejudices and to lose their fear of the unknown. They came into contact with the artistic influences that were part of their heritage, but from which distance had set them apart. The United States, just over 140 years old in 1920, was confident enough to start tracing its own roots. The people born around 1900 were the ones to do it, and at the same time to throw off the bourgeois and materialistic values of their parents. More prosaically, they could live very well indeed on a very few dollars, and unlike at home they could get a decent drink without risking their livers on bathtub gin. Many of them lived on allowances from those same ‘rejected’ parents.