Полная версия

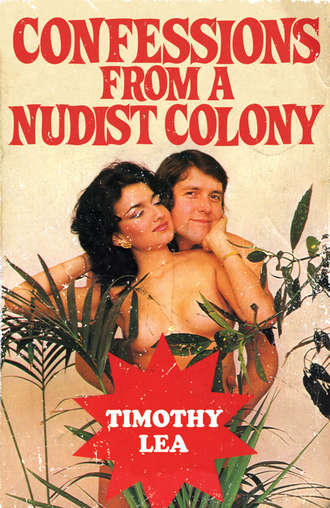

Confessions from a Nudist Colony

‘You ought to be more worried about the TV licence,’ says Mum. ‘We’ve had three reminders and you still haven’t done anything.’

‘What have you got there?’ asks Dad. Like a berk, I have raised my hands to grab the tea and Dad has clocked my wrists.

‘He’s got his cufflinks tangled,’ says Sid. ‘Nice, aren’t they? A bit on the large side but handsome.’

‘It’s nothing to be alarmed about,’ I say. ‘This bird thought I was something else – I mean someone else.’

‘Picked you out in an identity parade, did she?’ says Dad. ‘Don’t worry, my son. They’ll never make it stick. What did you do? Nick her handbag. Where is it?’

‘I didn’t nick anything,’ I say.

‘You don’t have to lie to me, son,’ says Dad. ‘I’m your father. I’ll stick by you. We may have our ups and downs but when the chips are down we Leas stick together.’

‘Look –’ says Sid.

‘Shut up!’ says Dad. ‘You led him into this, I suppose? Made him the catspaw for your evil designs. Played on his simple nature.’

‘What do you mean simple?’ I say.

‘Your father’s right, dear,’ says Mum. ‘Don’t let them put words into your mouth. Say you never touched the girl.’

‘I didn’t touch the girl,’ I say. ‘I mean, not like that I didn’t.’

‘Of course, it could go badly with him,’ says Dad. ‘There’s his criminal record to be taken into consideration.’

‘Don’t be daft!’ I say. ‘The only criminal record I’ve got is “The Laughing Policeman”.’

‘He laughs in the teeth of danger!’ says Sid. ‘Makes you proud, doesn’t it? Shall I start piling the furniture against the door? How long do you think we’ll be able to hold out? Better nip out and get a few cans of beans before they get round here.’

‘Shut up, Sid!’ I say. ‘You’re not funny. Haven’t we got anything stronger than this nail file, Dad?’

‘Of course!’ says he from whose loins I sprung with understandable haste. ‘Is that the best he could do for you, my son? Hang on a minute, I’ll get my blow torch.’

‘I’ll go quietly!’ I scream, leaping to the window.

‘Now see what you’ve done,’ says Sid. ‘You’ve inflamed his persecution mania. Why don’t you calm down and start baking him a cake with a file in it?’

‘Because, if his mother made it he’d never be able to bite through to the file,’ says Dad.

‘Walter!’ Mum is understandably upset. ‘How could you? Haven’t I made a nice home for you and the kiddies? Why do you have to say a thing like that? If you don’t like my cooking, you know what you can do.’

‘Yeah. Go on gobbling down the bicarbonate of soda like I do at the moment. Don’t make a scene for Gawd’s sake. There’s more important things to worry about.’

At this moment, fraught with unpleasantness and overhung by a thin veil of menace, the doorbell rings.

‘Who’s that?’ says Mum.

Sid takes a dekko through the lace curtain. ‘Blimey!’ he says. ‘It’s the fuzz!’

‘Don’t take the piss,’ I say, ‘Let me have a – oh no!’ Standing on the doorstep and tucking thoughtfully at his helmet strap is an enormous copper.

‘Right!’ says Dad. ‘I’ll handle this. You get out the back and pretend you’re pushing the lawnmower down to the shelter. I don’t want the neighbours to notice anything.’

‘They’ll notice you haven’t got a lawn,’ says Sid.

‘Shut up!’ says Dad.

‘Dad,’ I say. ‘I don’t think–’

‘I know you don’t,’ says Dad. ‘That’s why I have to do it for you. Now, get out there and stop arguing.’

‘Your father knows best,’ says Mum. ‘Stay in the shed till we come for you. Check there’s nobody round the back, Sid.’ When they go on like that you really feel that you have done something and I begin to wonder if my spot of in and out with Millie was against the law in more senses than one.

‘Right,’ says Dad. ‘Here we go.’

‘Don’t antagonise them, Walter,’ calls Mum.

‘You can rely on me,’ says Dad.

‘There’s nobody round the back,’ says Sid. ‘Come on, Bogart!’ He pushes me out of the back door as I hear Dad opening the front.

The lawmower Dad was talking about is another piece he has ‘saved’ from the lost property office where he is supposed to work. The only piece of grass in the back yard is growing between its rusty blades and the roller stops going round after two yards. I abandon it, not caring whether the neighbours are watching or not, and go and sit in the corrugated iron shelter which Dad kept from the last war and which now holds most of his world famous collection of gas masks. There is a large wooden wireless with a lot of fretwork on the front of it, a tattered copy of a magazine called John Bull and a Players fag packet with a bearded matelot as part of the design. This is where Dad must have repulsed Hitler. I wonder how he is doing with the fuzz? I am reading about how some geezer called Alvar Liddell planned his rock garden when Sid sticks his head round the door.

‘Well,’ he says. ‘They’ve gone.’

‘Oh good,’ I say. ‘Mum and Dad all right?’

‘It’s them that’s gone!’ says Sid. ‘Blimey, your old man didn’t half ask for it. The copper had only come round to tell him that the reflector on his bike had dropped out. Your Dad had his helmet off seconds after he opened the door. Screaming about a police state at the top of his voice, he was. Then your Mum waded in. She’s strong, isn’t she?’

‘When she gets worked up,’ I say. ‘Oh my Gawd. What did she do?’

‘Socked the copper round the mug with that wire basket of earth that used to have flowers in it. They were like wild animals. I don’t know what would have happened if the police car hadn’t gone past. It took three blokes to get them through the doors.’

‘What a diabolical mix-up,’ I say. ‘Poor old Dad. He was only trying to do his best, wasn’t he? It’s quite touching really.’

‘Yes,’ says Sid. ‘Blood is thicker than water and your old man is thicker than both. Don’t worry. You can make it up to him when we get the camping site organised. A nice little holiday by the sea is what they both need. It’ll set them up a treat.’

It occurs to me that for once in his life Sid is right. Mum and Dad do deserve some sort of perk after their brave but misguided attempt to save me from the nick. I only hope that Little Crumbling will be up their street.

‘It looks nice,’ says Sid as we study my old school atlas and have a cup of Rosie prior to nipping down the station and rescuing Mum and Dad – we find a file in the shelter that gets the cuffs off. ‘Little Crumbling, just next to Great Crumbling. You don’t know it, Timmo, do you? You were down that way once.’

Sid is referring to my experience as a Driving Instructor at Cromingham, emergent jewel of North Norfolk. (Shortly to become an epic movie, folks!)

‘I don’t remember it, Sid,’ I say. ‘Still, I didn’t get around much.’

‘Huh,’ says Sid. ‘You were in the back seat shafting the customers, weren’t you? Well, you can forget about that here. There’s going to be no hanky wanky on my site.’

‘I should hope not!’ I say. ‘Hanky panky would be distasteful enough. What are you planning to do, Sid?’

‘We’ll take the car down and spend a couple of days getting the lay of the land. Apparently a Mrs Pigerty lives on the site, but being of a nomadic disposition she could easily be prepared to part with it for a few quid.’

‘She’s a real gyppo, is she, Sid?’

Sid’s expression registers that he has taken exception to my remark. ‘A Romany, please,’ he says. ‘Steeped in ancient laws and crafts. They’re a noble people with their own language, you know. Just because they’re partial to baked hedgehog for Sunday lunch there’s no need to snoot your cock at them.’

‘No disrespect intended,’ I say. ‘I’ve often thought how pleasant it would be wandering over the breast of the down with the reins twitching between my fingers. Faithful Dobbin snatching at a wild rose as we wade fetlock-deep through verdant pastureland. The sun bouncing off the brightly painted shell of the caravan, the blackened cooking pot swinging lazily beside my earhole. The sweet smell of newly mown hay wafting—’

‘All right! All right!’ shouts Sid. ‘Blimey! Are you after an Arts Council grant or something?’

‘Just trying to get in the mood,’ I say. ‘Honeysuckle twisting round the porch and all that.’

‘Don’t start again,’ pleads Sid. ‘We’ll go and collect your Mum and Dad and set off tomorrow. Should take us about three hours, I reckon.’

In fact it is not easy to get Mum and Dad away from the rozzers. Not because they don’t want to let them go, but because Dad barricades himself in his cell and refuses to come out. As we come through the door we hear him shouting about a ‘fast to the death!’

‘How long’s he been on hunger strike?’ I ask.

‘He started just after he had his tea and biscuits,’ says the bloke behind the desk. ‘You his son, are you? Any history of mental disease in the family?’

‘We had a cousin who became a copper,’ I say.

‘Oh yes, highly whimsical,’ says the bule, slamming his book shut. ‘Listen, funny man. If you don’t get your father out of here in ten minutes, I’ll arrest the whole bleeding lot of you!’

‘Where’s my Mum?’ I say.

‘She’s in with your Dad,’ says the bule.

‘That’s nice,’ says Sid. ‘Family solidarity. Refused to be separated, did they?’

The copper looks a bit embarrassed. ‘They couldn’t be separated,’ he says. He turns round and shouts through a door behind him. ‘Millie! Have you found the keys to those blooming handcuffs, yet?’

It is pissing with rain most of the way up to the Norfolk coast but I don’t allow my spirits to flag. A couple of days out of the Smoke with Sid footing the bills is not to be sniffed at and I wonder where he has it in mind for us to stay, I hope we don’t have to share the same bedroom. You always get a few funny glances and one of the waiters rubbing his knee against you when he ladles out the brown windsor.

‘I’m looking forward to a bit of grub,’ I say, trying to raise the subject discreetly.

‘There should be some chocolate in the glove compartment,’ says Sid. ‘That’s if Jason hasn’t eaten it.’

‘I’m not quite certain whether he has or not,’ I say, examining the stomach-turning mess sticking to the 1955 AA Book.

‘Don’t throw it out of the window,’ says Sid. ‘It’s perfectly eatable once it’s firmed up again. You just want to make sure you don’t get a bit of silver paper against your fillings.’

‘I see there’s a hotel at Great Crumbling,’ I say. ‘Got a couple of rosettes and a lift for invalid chairs.’

‘Yes,’ says Sid. ‘We should be turning off about here. Do you notice how the air has changed?’

‘I think they must be spraying that field,’ I say.

‘I didn’t mean that!’ says Sid. ‘I was referring to the fact that it’s fresh. No smoke, no diesel fumes. We’re going to become new men out here. You know how healthy people look when they come back from their holidays? We’re going to be like that all the time.’

‘They’re skint when they come back from their holidays, too,’ I say.

Sid waves his arms into the air and nearly drives into a field of sugar beet. ‘There you go again. Money! That’s all you bleeding think about. Why don’t you put it behind you and look at the skyline?’

‘I’m sorry, Sid,’ I say. ‘I’ll probably feel better when we’ve checked in at the hotel.’ I wait hopefully but Sid tightens his grip on the wheel and gazes through the windscreen with a new sense of purpose.

‘Did you see that signpost?’ he says. ‘Little Crumbling two and a half miles. It was two miles at the signpost before that. You can tell we’re in the country.’

‘I think I’ll have a bath,’ I say. ‘Then a pot of tea in my room. And maybe a few rounds of hot buttered toast.’

Sid shoves on the anchors. ‘That sounds handy,’ he says.

‘Oh good,’ I say. ‘Maybe I’ll have a few teacakes as well.’

‘I meant that,’ says Sid.

I follow his nod and tilt my head to read a lop-sided sign which says ‘Bitter Vetch Farm. Visitors taken in. No travellers’. Beyond the sign is a muddy track leading to a cluster of dilapidated barns surrounding a building with a moulting thatched roof.

‘I don’t think they still do it,’ I say. ‘It looks deserted.’

‘It can’t be,’ says Sid. ‘There’s smoke coming from the roof.’

‘Maybe it’s on fire?’ I say hopefully.

‘Looks very authentic to me,’ says Sid. ‘You’ll get your food straight off the land there. It was just what you were talking about.’

‘Should be cheap as well,’ I say.

‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ says Sid.

‘No, of course not,’ I say. ‘I wonder you didn’t bring a sleeping bag.’

Sid’s eyes narrow thoughtfully and I wish I had kept my mouth shut. ‘You could stretch out in the back underneath the tiger skin rug,’ he says. ‘Mind your feet on the upholstery and don’t try and pee out of the window.’

‘Sounds very tempting, Sid.’ I say. ‘But I’ll give it a miss if you don’t mind.’

The farmyard has half a dozen bedraggled chickens picking their way round it and if their condition is an example of the fare available at Bitter Vetch Farm it is difficult to see why they should want to hang around, let alone us. Sid however does not seem to notice that they look like long-necked canaries and knocks boldly on the door. There is a moment’s pause and the door is opened by a comfortable Mum-type lady with flour all over her hands. These she wipes on the sheep which is lying on the kitchen table.

‘Good afternoon, madam,’ says Sid briskly. ‘I believe you take people in?’

The woman’s face hardens. ‘If you’m from the Milk Marketing Board you can take your long snouts off our farm! The water in them churns came through the roof. My Dan would never knowingly cheat anyone. He ain’t got the sense.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.