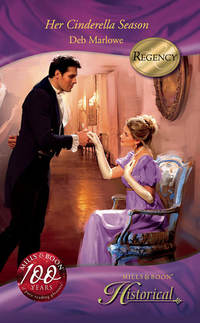

Полная версия

Her Cinderella Season

‘But surely you don’t believe that merriment and worthiness are mutually exclusive?’ Her father’s image immediately rose up in her mind. His quick smile and ready laugh were two of her most cherished memories. ‘I’m certain you will agree that it is possible to work hard, to become a useful and praiseworthy soul and still partake of the joy in life?’

‘The joy in life?’ Mr Cooperage appeared startled by the concept. ‘My dear, we were not put on this earth to enjoy life—’ He cut himself abruptly off. Lily could see that it pained him greatly. She suspected he wanted badly to inform her exactly what he thought her purpose on this earth to be.

Instead, he forced a smile. ‘I will not waste our few moments of conversation.’ He paused and began again in a lower, almost normal conversational tone. ‘I do thank you for your efforts today. However they are gained, I mean to put today’s profits to good use. I hope to accomplish much of God’s work in my time abroad.’

‘How impatient you must be to begin,’ she said, grateful for a topic on which they could agree. ‘I can only imagine your excitement at the prospect of helping so many people, learning their customs and culture, seeing strange lands and exotic sights.’ She sighed. ‘I do envy you the experience!’

‘You should not,’ he objected. ‘I donot complain. I will endure the strange lodgings, heathen food and poor company because I have a duty, but I would not subject a woman to the hardships of travel.’

She should not have been surprised. ‘But what if a woman has a calling such as yours, sir? What then? Or do you not believe such a thing to be possible?’

He returned her serious expression. ‘I believe it to be rare, but possible.’ He glanced back towards the park gate. ‘Your mother, I believe, has been called. I do think she will answer.’

Her mother had been called? To do what?

‘My mission will keep me from the shores of England for a little more than a year, Miss Beecham, but your good mother assures me that there are no other suitors in the wings and that a year is not too long a wait.’ He roamed an earnest gaze over her face. ‘Was she wrong?’

Lily took a step back. Surprise? He had succeeded in shocking her. ‘You wish my mother to wait for you, sir? Do you mean to court her?’

He chuckled. ‘Your modesty reflects well on you, my dear. No—it is you who I wish to wait for me. You who I mean to court most assiduously when I return.’

His eyes left her face, and darted over the rest of her. ‘Your mother was agreeable to the notion. I hope you feel the same?’

Lily stood frozen—not shocked, but numb. Completely taken aback. Mr Cooperage wished to marry her? And her mother had consented? It must be a mistake. At first she could not even wrap her mind about such an idea, but then she had to struggle to breathe as the bleak image of such a life swept over her.

‘Miss Beecham?’ Mr Cooperage sounded anxious, and mildly annoyed. ‘A year is too long?’ he asked.

She couldn’t breathe. She willed her chest to expand, tried to gasp for the air that she desperately needed. She was going to die. She would collapse to the ground right here, buried and suffocated under the weight of a future she did not want.

Her life was never going to change. The truth hit her hard, at last knocking the breath back into her starving lungs. She gasped out loud and Mr Cooperage began to look truly alarmed. Seven years. So long she had laboured; she had tried her best and squashed the truest part of her nature, all in the attempt to get her mother to look at her with pride. Was this, then, what it would take? The sacrifice of her future?

Lily took a step back, and then another. Only vaguely did she realise how close she had come to the busy street behind her. She only thought to distance herself from the grim reality of the life unfolding in front of her.

‘Miss Beecham!’ called Mr Cooperage. ‘Watch your step. Watch behind you!’ he thundered. ‘Miss Beecham!’

A short, heavy snort sounded near her. Lily turned. A team of horses, heads tossing wildly, surged towards her.

Her gaze met one wild, rolling eye. A call of fright rang out. Had she made the sound, or had the horse?

‘Miss Beecham!’

Chapter Two

Jack Alden pulled as hard as he dared on the ribbons. Pain seared its way up his injured arm. Pettigrew’s ill-tempered bays responded at last, subsiding to a sweating, quivering stop.

‘I warned you that these nags were too much for that arm,’ his brother Charles said. His hand gripped the side of the borrowed crane-neck phaeton.

‘Stow it, Charles,’ Jack growled. He stared ahead. ‘Hell and damnation, it’s a woman in the street!’

‘Well, no wonder that park drag ground to a halt. I told you when it started into the other lane that this damned flighty team would bolt.’

‘She’s not moving,’ Jack complained. Was the woman mad? Oblivious to the fact that she’d nearly been trampled like a turnip off a farm cart, she stood stock still. She wasn’t even looking their way now; her attention appeared focused on something on the pavement. Jack could not see just what held her interest with near deadly result. Nor could he see her face, covered as it was by a singularly ugly brown bonnet.

‘You nearly ran her down. She’s likely frozen in fear,’ Charles suggested.

‘For God’s sake!’ Jack thrust the reins into his brother’s hands and swung down. Another jolt of pain ripped through his arm. ‘Hold them fast!’ he growled in exasperation.

‘Do you know, Jack, people have begun to comment on the loss of your legendary detachment,’ Charles said as he held the bays in tight.

‘I am not detached!’ Jack said, walking away. ‘You make me sound like a freehold listing in The Times.’

‘Auction on London Gentleman, Manner Detached,’ his brother yelled after him.

Jack ignored him. Legendary detachment be damned. He was anchored fully in this moment and surging forwards on a wave of anger. The fool woman had nearly been killed, and by his hand! Well, that might be an exaggeration, but without doubt the responsibility would have been his. He’d caught sight of her over the thrashing heads of the horses—standing where she clearly did not belong—and fear and anger and guilt had blasted him like lightning out of the sky. The realisation that his concern was more for himself than for her only fuelled his fury.

‘Madam!’ he called as he strode towards her. The entire incident had happened so fast that the park drag had still not manoeuvred completely past. People milled about on the pavement, and one florid gentleman glared at the woman, but made no move to approach her.

‘Madam!’ No response. ‘If you are bent on suicide, might I suggest another man’s phaeton? This one is borrowed and I am bound to deliver it in one piece.’

She did not answer or even look at him. ‘Ma’am, do you not realise that you were nearly killed?’ He took her arm. ‘Come now, you cannot stand in the street!’

At last, ever so slowly, the bonnet began to turn. The infuriating creature looked him full in the face.

Jack immediately wished she hadn’t. He had grown up surrounded by beauty. He’d lived in an elegant house and received an excellent education. From ancient statuary to modern landscapes, between the sweep of grand architecture and the graceful curve of the smallest Sèvres bowl, he’d been taught to recognise and appreciate the value of loveliness.

This girl—she was the image of classic English beauty come to life. Gorgeous slate-blue eyes stared at him, but Jack had the eerie certainty that she did not see him at all. Instead she was focused on something far away, or perhaps deep inside. Red-gold curls framed high curving cheeks, smooth, ivory skin gone pale with fright and a slender little nose covered with the faintest smattering of freckles.

And her mouth. His own went dry—because all the fluids in his body were rushing south. A siren’s mouth: wide and dusky pink and irresistible. He stared, saw the sudden trembling of that incredibly plump lower lip—and he realised just what it was he was looking at.

Immense sorrow. A portrait of profound loss. The sight of it set off an alarm inside of Jack and awoke a heretofore unsuspected part of his character. He’d never been the heroic, knight-in-shining-armour sort—but that quivering lower lip made him want to jump into the fray. He could not quell the sudden urge to fight this unknown girl’s battles, soothe her hurts, or, better yet, kiss her senseless until she forgot what upset her and realised that there were a thousand better uses for that voluptuous mouth.

He swallowed convulsively, tightened his grip on her arm…and thankfully, came back to his senses. They stood in the middle of a busy London street. Catcalls and shouts and several anatomically impossible suggestions echoed from the surrounding bustle of stopped traffic. A begrimed coal carter had stepped forwards to help his brother calm the bays. Several of society’s finest, dressed for the daily strut and starved for distraction, gawked from the pavement.

‘Come,’ Jack said gently. Her steps wooden, the girl followed. He led her out of the street, past the sputtering red-faced gentleman, towards the Grosvenor Gate. Surely someone would claim her. He darted a glance back at the man who had fallen into step behind them. Someone other than this man—who had apparently left her to be run down like a dog in the street.

Lily was lost in a swirling fog. It had roiled up and out of her in the moment when she had fully understood her predicament. Her life was never going to change. Just the echo of that thought brought the mist suffocatingly close. She abandoned herself to it. She’d rather suffocate than contemplate the stifling mess her life had become.

Only vaguely was she aware that the stampeding horses had stopped. Dimly she realised that a stranger led her out of the street. The prickle of her skin told her that people were staring. She couldn’t bring herself to care.

‘Lilith!’ Her mother’s strident voice pierced the fog. ‘Lilith! Are you unharmed? What were you thinking?’

Anger and resentment surged inside of her, exploded out of her and blew a hole in the circling fog. It was big enough for her to catch a glimpse of her mother’s worried scowl as she hurried down from Mr Wilberforce’s barouche, and to take in the crowd forming around them.

Her gaze fell on the man who had saved her from herself and she forgot to speak. She stilled. Just at that moment a bright ray of sunlight broke free from the clouds. It shone down directly on to the gentleman, chasing streaks through his hair and outlining the masculine lines of his face. With a whoosh the fog surrounding her disappeared, swept away by the brilliant light and the intensity of the stranger’s stare.

Lily swallowed. The superstitious corner of her soul sprang to attention. Her heart began to pound loudly in her ears.

The clouds shifted overhead and the sunbeam disappeared. Now Lily could see the man clearly. Still her pulse beat out a rapid tune. Tall and slender, he was handsome in a rumpled, poetic sort of way. A loose black sling cradled one arm and, though it was tucked inside the dark brown superfine of his coat, she noticed that he held it close as if it ached.

His expression held her in thrall. He’d spoken harshly to her just a moment ago, hadn’t he? Now, though his colour was high, his anger seemed to have disappeared as quickly as her hazy confusion. He stared at her with an odd sort of bated hunger. A smile lurked at the edge of his mouth, small and secretive, as if it were meant just for her. The eyes watching her so closely were hazel, a sorry term for such a fascinating mix of green and gold and brown. Curved at their corners were the faintest laugh lines.

So many details, captured in an instant. Together they spoke to her, sending the message that here was a man with experience. Someone who knew passion, and laughter and pain. Here was a man, they whispered, who knew that life was meant to be enjoyed. ‘Lilith—’ her mother’s voice sounded irritated ‘—have you been hurt?’

Lily forced herself to look away from the stranger. ‘No, Mother, I am fine.’

Her mother continued to stare expectantly, but Lily kept quiet. For once, it was not she who was going to explain herself.

Thwarted, Mrs Beecham turned to Mr Cooperage, who lurked behind the strange gentleman. ‘Mr Cooperage?’ was all that she asked.

The missionary flushed. ‘Your daughter does not favour…’ he paused and glanced at the stranger ‘…the matter we discussed last week.’

‘Does not favour—?’ Lilith’s mother’s lips compressed to a foreboding thin line.

Mr Cooperage glanced uneasily at the man again and then at the crowd still gathered loosely around them. ‘Perhaps you might step aside to have a quiet word with me?’ His next words looked particularly hard for him to get out. ‘I’m sure your daughter would like the chance to… thank…this gentleman?’

‘Mr…?’ Her mother raked the stranger with a glare, then waited with a raised brow.

The stranger bowed. Lily thought she caught a faint grimace of pain in his eyes. ‘Mr Alden, ma’am.’

‘Mr Alden.’ Her mother’s gaze narrowed. ‘I trust my daughter will be safe with you for a moment?’

‘Of course.’

The crowd, deprived of further drama, began to disperse. Lily’s mother stepped aside and bent to listen to an urgently whispering Mr Cooperage. Lily did not waste a moment considering them. She knew what they discussed. She remembered the haze that had almost engulfed her. It had swept away and left her with a blinding sense of clarity.

‘I admit to a ravening curiosity.’ MrAlden spoke low and his voice sounded slightly hoarse. It sent a shiver down Lily’s spine. ‘Do you wish to?’ He raised a questioning brow at her.

‘I’m sorry, sir. Do I wish to what?’

‘Wish to thank me for nearly running you down in the street while driving a team I clearly should not have been?’ He gestured to the sling. ‘I assure you, I had planned to most humbly beg your pardon, but if you’d rather thank me instead…’

Lily laughed. She did not have to consider the question. The answer, along with much else, was clear at last. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘even when you phrase it in such a way. I do wish to thank you.’

He looked a little taken aback, and more than a little interested. ‘Then you must be a very odd sort of female,’ he said. She felt the heat of the glance that roamed over her, even though he had assumed a clinical expression. ‘Don’t be afraid to admit it,’ he said. He leaned in close, as if confiding a secret. ‘Truly, the odd sorts of females are the only ones I can abide.’ He smiled at her.

She stared. His words were light and amusing, but that smile? It was wicked. ‘Ah, but can they abide you, sir?’

The smile vanished. ‘Perhaps the odd ones can,’ he said.

The words might have been cynical, or they might have been a joke. Lily watched his face closely, looking for a clue, but she could not decipher his expression. His eyes shone, intense as he spoke again.

‘So, tell me…’ He lowered his voice a bit. ‘What sort of female are you, then?’

No one had ever asked her such a thing. She did not know how to answer. The question stumped her—and made her unbearably sad. That clarity only extended so far, it would seem.

‘Miss?’ he prompted.

‘I don’t know,’ she said grimly. ‘But I think it is time I found out.’

The shadow had moved back in, Jack could see it lurking behind her eyes. And after he’d worked so hard to dispel it, too.

Work was an apt description. He was not naturally glib like his brother. He had no patience with meaningless societal rituals. A little disturbing, then, that it was no chore to speak with this woman.

She stirred his interest—an unusual occurrence with a lady of breeding. In Jack’s experience women came in two varieties: those who simulated emotion for the price of a night, and those who manufactured emotion for a tumultuous lifetime sentence.

Jack did not like emotion. It was the reason he despised the tense and edgy stranger he had lately become. He understood that emotion was an integral part of human life and relationships. He experienced it frequently himself. He held his family in affection. He respected his mentors and colleagues. Attraction, even lust, was a natural phenomenon he allowed himself to explore to the fullest. He just refused to be controlled by such sentiments.

Emotional excess invariably became complicated and messy and as far as he’d been able to determine, the benefits rarely outweighed the consequences. Scholarship, he’d discovered, was safe. Reason and logic were his allies, his companions, his shields. If one must deal with excessive emotions at all, it was best to view them through the lens of learning. It was far more comfortable, after all, to make a study of rage or longing than to experience it oneself. Such things were of interest in Greek tragedy, but dashed inconvenient in real life.

Logic dictated, therefore, that he should have been repelled by this young beauty. She reeked of emotion. She had appeared to be at the mercy of several very strong sensations in succession. Jack should have felt eager to escape her company.

But as had happened all too frequently in the last weeks, his reason deserted him. He was not wild to make his apologies and move on. He wanted to discover how she would look under the onslaught of the next feeling. Would those warm blue eyes ice over in anger? Could he make that gorgeous wide mouth quiver in desire?

‘Mister Alden.’

His musings died a quick death. That ringing voice was familiar.

‘Lady Ashford.’ He knew before he even turned around.

‘I am unsurprised to find you in the midst of this ruckus, Mr Alden.’ The countess skimmed over to them and pinned an eagle eye on the girl. ‘But you disappoint me, Miss Beecham.’

The name reverberated inside Jack’s head, sending a jolt down his spine. Beecham? The girl’s name was Beecham? It was a name that had weighed heavily on his mind of late.

They were joined again by the girl’s mother and the red-faced Mr Cooperage, but Lady Ashford had not finished with the young lady.

‘There are two, perhaps three, men in London who are worth throwing yourself under the wheels of a carriage, Miss Beecham. I regret to inform you that Mr Alden is not one of them.’

No one laughed. Jack was relieved, because he rather thought that the countess meant what she said.

Clearly distressed, the girl had no answer. Jack was certainly not fool enough to respond. Fortunately for them both, someone new pushed her way through the crowd. It was his mother, coming to the rescue.

Lady Dayle burst into their little group like a siege mortar hitting a French garrison. Passing Jack by, she scattered the others as she rushed to embrace the girl like a long-lost daughter. She clucked, she crooned, she examined her at arm’s length and then held her fast to her bosom.

‘Jack Alden,’ she scolded, ‘I could scarcely believe it when I heard that you were the one disrupting the fair and causing such a frenzy of gossip! People are saying you nearly ran this poor girl down in the street!’ Her gaze wandered over to the phaeton and fell on Charles. He gave a little wave of his hand, but did not leave the horses.

‘Charles! I should have known you would be mixed up in this. Shame on the pair of you!’ She stroked the girl’s arm. ‘Poor lamb! Are you sure you are unhurt?’

Had Jack been a boy, he might have been resentful that his mother’s attention was focused elsewhere. He was not. He was a man grown, and therefore only slightly put out that he could not show the girl the same sort of consideration.

Mrs Beecham looked outraged. Miss Beecham merely looked confused. Lady Ashford looked as if she’d had enough.

‘Elenor,’ the countess said, ‘you are causing another scene. I do not want these people to stand and watch you cluck like a hen with one chick. I want them to go inside and spend their money at my fair. Do take your son and have his arm seen to.’

‘Oh, Jack,’ his mother reproved, her arm still wrapped comfortingly about the girl. ‘Have you re-injured your arm?’

Lady Ashford let her gaze slide over the rest of the group. ‘Elenor dear, do let go of the girl and take him to find out. Mr Cooperage, you will come with me and greet the women who labour in your interest today. The rest of you may return to what you were doing.’

‘Lilith has had a fright, Lady Ashford,’ Mrs Beecham said firmly. ‘I’ll just take her back to our rooms.’

‘Nonsense, that will leave the Book Table unattended,’ the countess objected.

‘Nevertheless…’ Mrs Beecham’s lips were folded extremely thin.

‘I shall see to her,’ Lady Dayle declared. ‘Jack, can you take us in your… Oh, I see. Whose vehicle are you driving, dear? Never mind, I shall just get a hackney to take us home.’

Mrs Beecham started to protest, and a general babble of conversation broke out. It was put to rout by Lady Ashford. ‘Very well,’ she declared loudly and everyone else fell silent. ‘You can trust Lady Dayle to see to your daughter, Mrs Beecham. I will take you to fetch the girl myself once the day is done.’

She paused to point a finger. ‘Mr Wilberforce’s barouche is still here. I’m certain he will not mind dropping the pair of them off,’ she said, ‘especially since he has only just made you a much larger request. I shall arrange it.’ She beckoned to the missionary. ‘Mr Cooperage, if you would come with me?’

Everyone moved to follow the countess’s orders. Not for the first time, Jack thought that had Lady Ashford been a man, the Peninsular War might have been but a minor skirmish.

With a last, quick glance at the girl on his mother’s arm, he turned back to his brother and the cursed team of horses.

But Lady Ashford had not done with him. ‘Are those Pettigrew’s animals, Mr Alden?’ she called. She did not wait for an answer. ‘Take yourself on home and see to your arm—and do not let Pettigrew lure you into buying those bays. I hear they are vicious.’

‘Thank you for the advice, Lady Ashford,’ he said, and, oddly, he meant it. Charles stood, a knowing grin spreading rapidly across his face.

‘Not a word, Charles,’ Jack threatened.

‘I wasn’t going to say a thing.’

Wincing, Jack climbed up into the rig and took up the ribbons. Charles took his seat beside him and leaned back, silent, but with a smile playing about the corners of his mouth.

‘The girl’s surname is Beecham.’

Charles sat a little straighter. ‘Beecham?’ he repeated with studied nonchalance. ‘It’s a common enough name.’

‘It’s that shipbuilder’s name and you know it, Charles. The man who is supposedly mixed up with Batiste.’

His brother sighed. ‘It’s not your responsibility to bring that scoundrel of a sea captain to justice, Jack.’

Jack stilled. A wave of frustration and anger swept over him at his brother’s words. He fought to recover his equilibrium. This volatility was unacceptable. He must regain control.

‘I know that,’ he said tightly. ‘But I can’t focus on anything else. I keep thinking of Batiste skipping away without so much as a slap on the hand.’ Charles was the only person to whom Jack had confided the truth about his wound and the misadventures that had led to it. Even then, there were details he’d been honour-bound to hold back. ‘It’s bad enough that the man is a thief and a slaver as well. But by all accounts the man is mad—I worry that he might come after old Mervyn Latimer again, or even try to avenge himself on Trey and Chione.’

It wasn’t Charles’s fault that he couldn’t understand. Though he knew most of the story, he didn’t know about the aftermath. Jack didn’t want him—or anyone else—to know how intensely he’d been affected. Charles must never know about his nightmares. He didn’t understand himself how or why all this should have roused his latent resentment towards their cold and distant father, but one thing he did know—he would never burden Charles with the knowledge. His older brother had his own weighty issues to contend with in that direction.