Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

The alternating temperate and cold stages of the pre-glacial Lower Pleistocene occupied about the first three-quarters of the epoch, some one and a half million years, leaving only half or at most three quarters of a million years for the more spectacular events of the Middle and Upper Pleistocene. The flora of the different stages, and consequently the nature of the contemporary climate, are inferred from a study of pollen analyses and the invertebrate and vertebrate faunas. Throughout this immense period of time the fauna appears to have changed little in composition. The mammalian fossils known from the deposits laid down in the British Isles during the Lower Pleistocene include giant beavers, voles, bears, a panda, hyaenas, sabre-toothed and other cats, elephants and mastodons, horses and zebras, a tapir, rhinoceros, deer and oxen, all of extinct species, together with the still existing beaver and red fox.

This list does not represent a large fauna for so long a period of time but when we remember that, with the exception of a few species known from the cave deposits in Dove Holes, Derbyshire, all are from marine deposits, it is not surprising that it is short. The carcases of animals washed into the sea soon decay and disintegrate so that the bones are scattered and the most durable parts, the teeth, are those more likely to be preserved in marine deposits. The Nodule Bed of the Red Crag, as mentioned above, contains a mixture of fossils. We can well imagine the sea eroding the cliffs of Pliocene or earlier epochs, and then rolling and polishing the released fossils on the beach until they were again buried in new deposits, just as today the fossils of the Crag can be found lying loose on the beach. Some of the fossils thus represent animals that were not members of the Lower Pleistocene fauna, for example the tapir, three-toed horse, and the panda.

The Middle Pleistocene began with a temperate stage, the Pastonian, which was followed by a cold subarctic stage, the Beestonian; this gave way to another temperate stage, the Cromerian, which preceeded the onset of widespread glaciation. The deposits of the Pastonian are marine sands and gravels known as the Weybourne Crag, the lower part of which was laid down in the Baventian stage of the Lower Pleistocene. The stages that follow are represented by the Cromer Forest Bed series which includes both marine and freshwater sediments and contains many mammalian fossils. A comparatively large mammalian fauna has been recorded from these beds; some species can be assigned to the cooler or to the temperate stages, but the exact position of many remains doubtful.

The fauna of the temperate Pastonian stage included extinct species of ground squirrel, beaver, voles, mammoth, horse, rhinoceros, deer and bison, as well as the still existing wolf, otter, wild boar and hippopotamus. Some of these species may belong to the succeeding cold Beestonian stage when the ground was frozen with permafrost in places, but it has not been possible to reconstruct the mammalian fauna of the stage; it was probably reduced in variety and confined to arctic species.

The rich fauna of the temperate Cromerian stage has yielded a great quantity of fossils that have been collected and studied for nearly two hundred years. Many of them, however, cannot be assigned to the various zones into which modern research has divided the stage because, as already mentioned, the early collectors did not appreciate the importance of recording the exact horizons from which they took their specimens. The mammals living during this stage included a monkey, many different species of rodent large and small, many carnivores from wolf and red fox to hyaenas, lion and sabre-tooth. The ‘big game’ were well represented with elephants and mammoth, horses and zebras, rhinoceros, wild boar and hippopotamus, giant and smaller deer, bison, aurochs, musk ox and sheep.

Some of the species of this extensive list are typical of colder climates such as the ground squirrel, pine vole, glutton, and musk ox; and others of warmer ones such as the monkey, spotted hyaena and hippopotamus. The majority, on the other hand, are species that might live under a temperate climate like that of the present day in the British Isles. When the Cromerian stage drew towards its end the climate became cooler, and mixed oak forest was replaced by boreal forest with pines and birch, and with open heaths, until the Anglian glacial stage wiped out most of the flora and probably all of the mammalian fauna. The history of the present mammalian fauna of the British Isles must therefore start at the end of the Anglian glaciation, which wiped the slate clean for a new start, leaving us only a few tons of fossil bones from which to infer what had gone before.

It is not surprising that hardly any mammalian fossils are known from the Anglian glaciation, for at its severest the southern part of the country, the only part that was not covered by the deep ice sheet, was an arctic desert. The few that have been found are assigned to the early or late parts of the stage when glaciation was developing or retreating – a ground squirrel to the former and the red deer to the latter. As, furthermore, no vertebrate fossils of other classes are known from the Anglian the conclusion that the glaciation exterminated the entire mammalian fauna is inescapable. The deposits of the Anglian stage are a complicated series of tills, including the Boulder Clay, produced by the ice moving in different directions at different times as the glaciation proceeded.

When the ice at last retreated the temperate flora and fauna of the Hoxnian stage gradually moved in from the continent as the desert gave way to tundra, then to boreal forest followed by mixed oak forest. The fossils of this interglacial stage are preserved mainly in freshwater deposits, though some marine and estuarine deposits exist from its later part. It was during this stage, too, that man first made his way into the British Isles, for his palaeolithic flint artifacts have been found in several places. The former claim that man had been present at a much earlier time is now discredited – the ‘eoliths’ from the Crag that were supposed to be primitive tools are no more than fortuitously broken stones. The only skeletal remains of alleged palaeolithic man living in the Hoxnian stage that have been found in the British Isles are some fragments of a skull from the Thames terrace gravel at Swanscombe, Kent. One bit of the skull was found in 1935, another in 1936, and a third in 1955. Although Oakley in 1969116 tabulated the Swanscombe skull, among the ‘early Neanderthaloids’ dating from about a quarter of a million years ago, the fragments, the occipital and two parietal bones, are indistinguishable from those of modern man. Since then there has been some controversy about the dating of the Hoxnian interglacial119’ 127; but a dating of material from ‘a few centimetres below’ the horizon of the Swanscombe skull gave ages of up to more than 272,000 years.139 This, unfortunately, does not give irrefutable proof of the age of the skull, and still leaves open the possibility advocated by some that the skull fragments may have become included in the gravel as intrusions at a later date. With the possible exception of the Swanscombe skull, the earliest remains of man in the British Isles, apart from his artifacts, date from the middle of the Devensian glaciation, at least some two hundred thousand years later.

The Hoxnian mammalian fauna that moved in from the continent differed from that of the Cromerian, although many species were the same, or similar, such as the beaver, some voles, the wolf, marten, lion, boar, the straight-tusked elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus, and the red, fallow, and roe deer. New arrivals included the arctic lemming, several voles, the cave bear, two species of rhinoceros replacing Diceros etruscus, Megaceros giganteus replacing several other species of giant deer, and the aurochs. Those that did not return, or were by then extinct, included the vole genus Mimomys, the sabre-tooth, the southern elephant, etruscuan rhinoceros, hippopotamus, zebrine horses, several species of deer, giant deer, and elks, the bison and musk ox.

When the climate became colder with the onset of the Wolstonian glaciation which reached its peak about 140,000 years ago, the fauna became more typically arctic, and those parts of the country not covered with ice were inhabited by hamsters, the arctic, Norway and steppe lemmings, the woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigeneus, the woolly rhinoceros, Coelodonta antiquitatis, and the reindeer Rangifer tarandus.

At the end of the Wolstonian stage, about 120,000 years ago, the temperate Ipswichian interglacial stage began and lasted about 50,000 years. The climate and flora followed the usual sequence of an interglacial stage, the temperature reaching a peak higher, however, than that of the present day, and the flora progressing from arctic tundra to boreal forest, mixed oak forest and then regressing by similar steps to the onset of the next glaciation. Mammalian remains of the Ipswichian occur in river and lake gravels, muds, and brick earths, and in the deposits of some caves. Many of the mammals are species that form part of our present day fauna, and include the bank, water and field voles, the wood mouse, the red fox, badger, and wild cat, the red, fallow and roe deer; and some extinct only in historic times such as the beaver, wolf, brown bear, wild boar and aurochs. The cooler parts of the stage were also marked by the presence of ground squirrels, the woolly mammoth and the musk ox, whereas the warmer parts supported the spotted hyaena, the lion, the straight-tusked elephant, two kinds of rhinoceros, the giant deer, and the hippopotamus, the last indicating a comparatively high temperature as does the presence of the European pond-tortoise Emys orbicularis. Palaeolithic man, as shown solely by his artifacts, was present throughout the stage.

The following Devensian glaciation began about 70,000 years ago and lasted nearly sixty thousand years until it came to an end rather quickly about 10,000 years ago. It was the least severe of the three great glaciations as it left southern England and the midlands free of ice and thus a possible habitat for many species that can withstand a cold climate. During this stage the sea fell some three hundred feet below its present level so that England was widely connected with the continent over the site of the southern part of the North Sea, and northern Ireland was narrowly connected with southern Scotland. Stuart136 remarks that the vast majority of Pleistocene vertebrate remains found in the British Isles, excluding post-glacial material, is probably of Devensian age. Most of the remains are found in river gravels and caves, some of the later ones in lake sediments. The flora of the ice-free regions was mostly tundra or open grassland, with some patches of boreal forest during short interstadial recessions of glaciation.

The fauna is typical of cold regions, though it includes some species of our present fauna such as the common shrew, the bank, water and field voles, the mountain hare, the fox, stoat, polecat, and red deer. Some of the species are not now associated with severely cold climates but nevertheless can withstand more cold than might be supposed; these are the leopard, lion, and spotted hyaena. On the other hand there are many species typical of colder habitats: a pika Ochotona, ground squirrel, the arctic lemming, several voles including the northern and tundra voles Microtus oeconomus and M. gregalis, the arctic fox Alopex, polar bear, glutton, woolly mammoth which became extinct at the peak of the glaciation about 18,000 years ago, woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, and musk ox. Several other large mammals left abundant remains in gravel and cave deposits; they include the wolf, the brown and cave bears Ursus arctos and U. spelaeus, a sabre-tooth Homotherium, the horse, giant deer, elk, a bison Bison priscus, and the aurochs.

Man returned after the peak of the Devensian glaciation as shown by his artifacts and by a few skeletal remains.30 Some human teeth of middle Devensian age from Picken’s Hole cave in Somerset are the earliest human remains known in the British Isles apart from the Swanscombe skull whose alleged age has been challenged by some people. The largest find of palaeolithic man belongs to the late Devensian deposits of Aveline’s Hole in the Mendip Hills of Somerset, where bones representing thirty-one skeletons were excavated.

As the ice melted during the late glacial stage of the Devensian the climate became milder and reached a peak after about a thousand years in the Allerød interstadial or ‘amelioration’ as it is sometimes called, though amelioration could have a different meaning for a reindeer than for a red deer. Thereafter the climate again became colder until about 10,000 years ago when the ice finally disappeared inaugurating the Flandrian interglacial which has lasted until the present. By the end of the late glacial many of the large mammals had become extinct, although there appears to be no reason why they should not have survived into the Flandrian. Perhaps the change of climate and the resulting changes in vegetation deprived them of their ecological niches, but it is also possible that improved hunting skills of upper palaeolithic man may have overcropped and thus exterminated them. The few species not part of our present mammalian fauna that survived from the late glacial disappeared in the early part of the Flandrian, which is discussed in the next chapter.

CHAPTER 3

THE EVOLUTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT

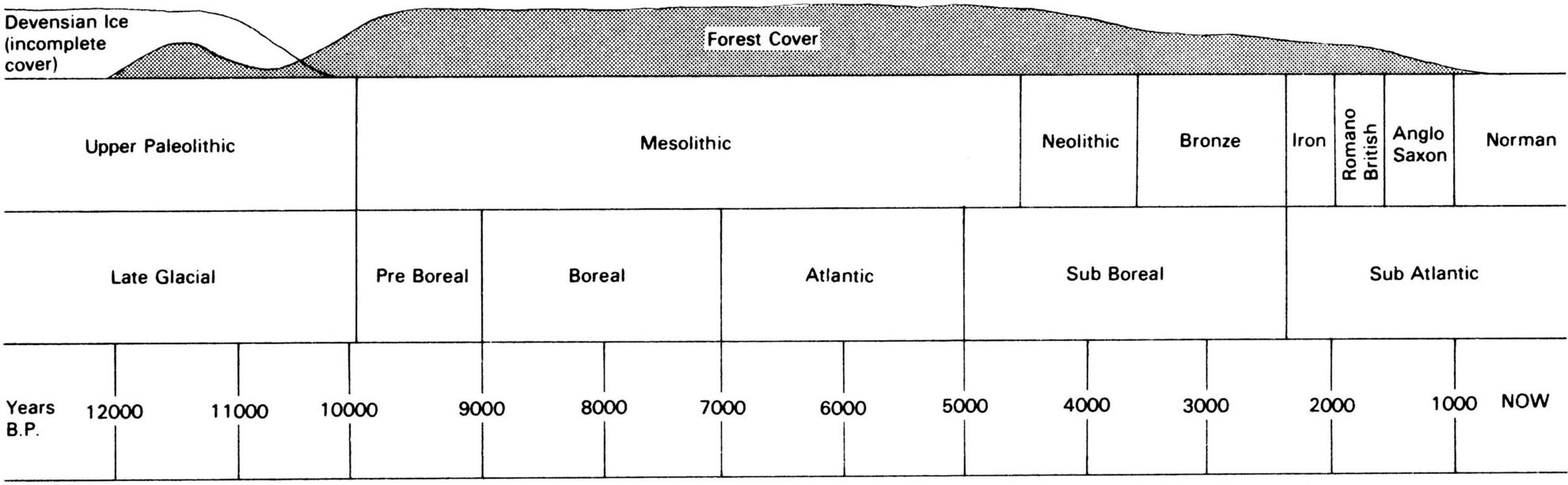

AT the beginning of the Flandrian stage, when the glaciation started to recede, the climate became warmer and thereafter varied between warmer and cooler so that it is convenient to subdivide the stage according to the prevailing climate of the time. In the first, Preboreal, phase the frost tundra of the country south of the ice began to be covered with growths of the dwarf or arctic birch, a shrub with stems and branches generally spreading over the ground and making a bush only a couple of feet or so high in sheltered places; it is a characteristic plant of the arctic and high mountains. It was followed by the tree birches spreading to make a forest so that in the following Boreal phase, when they were joined by pine and hazel, the forest cover was complete. During the Boreal phase the melting of the ice brought a rapid rise in the level of the sea which finally cut through the Strait of Dover about 7,000 years ago, whereas the southern part of the North Sea and eastern end of the English Channel had been dry at the beginning of the Pre-boreal. At the same time the climate became several degrees warmer than at present, producing the Atlantic phase, during which the forest cover was enriched by the addition of oak, and alder. Thereafter the climate became cooler about 4,500 years ago, introducing the Sub-boreal phase, and the forest was further enriched by ash, elm and lime. A minor rise in sea level marked the end of the Sub-boreal phase about 2,250 years ago, and the climate entered the Sub-atlantic phase that we endure at the present day.

At about the end of the Devensian glaciation the upper palaeolithic culture that man had evolved through many grades during the middle Pleistocene, was succeeded by the mesolithic culture characterised by the small flint artifacts called ‘microliths’. Of the several known mesolithic occupational sites, that at Starr Carr near Scarborough in Yorkshire has been meticulously excavated by Professor J. Clark and his colleagues, who have been able to draw a picture of the life of the inhabitants, and of the fauna and flora.35 The site was occupied about 9,500 years ago as a winter hunting camp by three or four families of nomadic people; the settlement lay at the edge of a lake in the Vale of Pickering, with closed birch forest on the hill rising behind and willows along the reedy shore. The people lived on a platform of birch brushwood and were occupied not only in hunting and gathering roots of reeds and bog-bean, but also in knapping flint to make tools, some of which were used for making barbed spearheads from slivers cut from the antlers of red deer. The bones and antlers they left on the site show that they lived mostly on the flesh of red deer, but that they also killed roe deer, elk, aurochs and wild boar in lesser numbers. They had no domestic animals, and did not cultivate any crops. The remains of other mammals show that the fauna included the pine marten, fox, wolf, badger, hedgehog, hare and beaver.

Fig. 5. The Flandrian succession in the British Isles after the ice of the Devensian glaciation melted.

This late Pre-boreal fauna shows that forest animals, the deer and aurochs, had replaced the tundra-living mammals such as the reindeer, bison and wild horse while the birch forest increased with the rise in temperature. Until the rise in sea level at the end of the Preboreal phase, although Ireland had long been separated from Great Britain, the site of the southern part of the North Sea was dry land with the coast line extending from Flamborough Head to Jutland with a northern loop including the Dogger Bank. At the same time the English Channel extended no further east than Beachy Head.

The mesolithic people remained in occupation for over five thousand years, during which the sea level rose and cut off the British Isles from the continent. About 4,500 years ago the neolithic people arrived, migrating across the sea from the east, and soon completely replaced the mesolithic culture with their own. Throughout the many hundreds of thousands of years of the preceding part of the Pleistocene the palaeolithic and later the mesolithic people were no more than part of the fauna, and produced no appreciable alteration in the environment. They were plant gatherers and hunters and, though they may have contributed towards the extinction of some of the large mammals such as the mammoth, their influence on the composition of the fauna was in general negligible. They probably had to work hard to earn their living in the British Isles, but further south on the continent, where the climate was milder and food abundant, they appear to have satisfied their wants more easily so that they had enough leisure to make paintings on the walls of caves, to make sculptures and carvings, and to engrave stones and bone artifacts with abstract and representational designs.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.