Полная версия

The Royal Succession

‘History is a novel that has been lived’

E. & J. DE GONCOURT

‘It is terrifying to think how much research is needed to determine the truth of even the most unimportant fact’

STENDHAL

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Foreword

The Characters in this Book

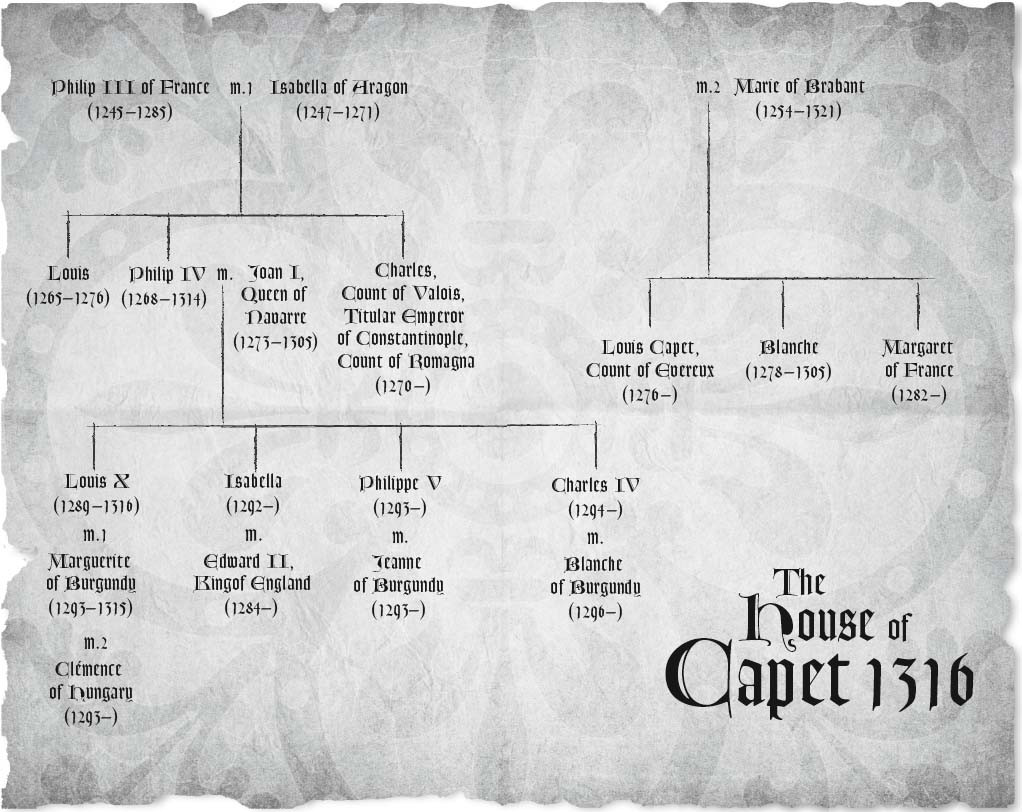

Family Tree

The Royal Succession

Prologue

Part One: Philippe and the Closed Gates

1. The White Queen

2. The Cardinal who Did not Believe in Hell

3. The Gates of Lyons

4. Let us Dry our Tears

5. The Gates of the Conclave

6. From Neauphle to Saint-Marcel

7. The Gates of the Palace

8. The Count of Poitiers’s Visits

9. Friday’s Child

10. The Assembly of the Three Dynasties

11. The Betrothed Play Tag

Part Two: Artois and the Conclave

1. The Arrival of Count Robert

2. The Pope’s Lombard

3. The Wages of Sin

4. We Must Go to War

5. The Regent’s Army Takes a Prisoner

Part Three: From Mourning to Coronation

1. A Wet-nurse for the King

2. Leave it to God

3. Bouville’s Trick

4. My Lords, Look on the King

5. A Lombard in Saint-Denis

6. France in Firm Hands

7. Shattered Dreams

8. Departures

9. The Eve of the Coronation

10. The Bells of Rheims

Historical Notes

Footnotes

Author’s Acknowledgments

By Maurice Druon

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

GEORGE R.R. MARTIN

Over the years, more than one reviewer has described my fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire, as historical fiction about history that never happened, flavoured with a dash of sorcery and spiced with dragons. I take that as a compliment. I have always regarded historical fiction and fantasy as sisters under the skin, two genres separated at birth. My own series draws on both traditions … and while I undoubtedly drew much of my inspiration from Tolkien, Vance, Howard, and the other fantasists who came before me, A Game of Thrones and its sequels were also influenced by the works of great historical novelists like Thomas B. Costain, Mika Waltari, Howard Pyle … and Maurice Druon, the amazing French writer who gave us the The Accursed Kings, seven splendid novels that chronicle the downfall of the Capetian kings and the beginnings of the Hundred Years War.

Druon’s novels have not been easy to find, especially in English translation (and the seventh and final volume was never translated into English at all). The series has twice been made into a television series in France, and both versions are available on DVD … but only in French, undubbed, and without English subtitles. Very frustrating for English-speaking Druon fans like me.

The Accursed Kings has it all. Iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception, family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she-wolves, sin, and swords, the doom of a great dynasty … and all of it (well, most of it) straight from the pages of history. And believe me, the Starks and the Lannisters have nothing on the Capets and Plantagenets.

Whether you’re a history buff or a fantasy fan, Druon’s epic will keep you turning pages. This was the original game of thrones. If you like A Song of Ice and Fire, you will love The Accursed Kings.

George R.R. Martin

The Characters in this Book

THE QUEEN OF FRANCE:

CLÉMENCE OF HUNGARY, grand-daughter of Charles II of Anjou-Sicily and of Marie of Hungary, second wife and widow of Louis X, the Hutin, King of France and Navarre, aged 23.

LOUIS X’S CHILDREN:

JEANNE OF NAVARRE, daughter of Louis X and his first wife, Marguerite of Burgundy, aged 5. JEAN I, called THE POSTHUMOUS, son of Louis X and Clémence of Hungary, King of France.

THE REGENT:

PHILIPPE, second son of Philip IV, the Fair, and brother to Louis X, Count of Poitiers, Peer of the Kingdom, Count Palatine of Burgundy, Lord of Salins, Regent, then Philippe V, the Long, aged 23.

HIS BROTHER:

CHARLES, third son of Philip the Fair, Count de La Marche and future King Charles IV, the Fair, aged 22.

HIS WIFE:

JEANNE OF BURGUNDY, daughter of Count Othon of Burgundy and of the Countess Mahaut of Artois, heiress to the County of Burgundy, aged 23.

HIS CHILDREN:

JEANNE, also called of Burgundy, aged 8.

MARGUERITE, aged 6.

ISABELLE, aged 5.

LOUIS-PHILIPPE of France.

THE VALOIS BRANCH:

MONSEIGNEUR CHARLES, son of Philippe III and of Isabella of Aragon, brother of Philip the Fair, Count of the Appanage of Valois, Count of Maine, Anjou, Alençon, Chartres, Perche, Peer of the Kingdom, ex-Titular Emperor of Constantinople, Count of Romagna, aged 46.

PHILIPPE OF VALOIS, son of the above and of Marguerite of Anjou-Sicily, the future King Philippe VI, aged 23.

THE EVREUX BRANCH:

MONSEIGNEUR LOUIS OF FRANCE, son of Philippe III and of Marie of Brabant, half-brother of Philip the Fair and of Charles of Valois, Count of Evreux and Etampes, aged 40.

PHILIPPE OF EVREUX, his son.

THE CLERMONT-BOURBON BRANCH:

ROBERT, COUNT OF CLERMONT, sixth son of Saint Louis, aged 60.

LOUIS OF BOURBON, son of the above.

THE ARTOIS BRANCH, DESCENDED FROM A BROTHER OF SAINT LOUIS:

THE COUNTESS MAHAUT OF ARTOIS, Peer of the Kingdom, widow of the Count Palatine Othon IV, mother of Jeanne and Blanche of Burgundy, mother-in-law of Philippe of Poitiers and of Charles de La Marche, aged about 45.

ROBERT III OF ARTOIS, nephew of the above, Count of Beaumont-le-Roger, Lord of Conches, aged 29.

THE DUCHY OF BURGUNDY FAMILY:

AGNÈS OF FRANCE, youngest daughter of Saint Louis, dowager Duchess of Burgundy, widow of Duke Robert II, mother of Marguerite of Burgundy, aged about 57.

EUDES V, her son, Duke of Burgundy, brother of Marguerite and uncle of Jeanne of Navarre, aged about 35.

THE COUNTS OF VIENNOIS:

THE DAUPHIN JEAN II de la Tour du Pin, brother-in-law of Queen Clémence.

THE DAUPHINIET GUIGUES, his son.

THE GREAT OFFICERS OF THE CROWN:

GAUCHER DE CHÂTILLON, Constable of France.

RAOUL DE PRESLES, jurist, one-time Councillor to Philip the Fair.

MILLE DE NOYERS, jurist, one-time Marshal of the Army, brother-in-law of the Constable.

HUGUES DE BOUVILLE, one-time Grand Chamberlain to Philip the Fair.

THE SENESCHAL DE JOINVILLE, companion-in-arms to Saint Louis, a chronicler.

ANSEAU DE JOINVILLE, son of the above, Councillor to the Regent.

ADAM HÉRON, Grand Chamberlain to the Regent.

COUNT JEAN DE FOREZ.

JEAN DE CORBEIL and JEAN DE BEAUMONT, called the Déramé, Marshals.

PIERRE DE GALARD, Grand Master of the Crossbowmen.

ROBERT DE GAMACHES and GUILLAUME DE SERIZ, Chamberlains.

GEOFFROY DE FLEURY, Bursar.

THE CARDINALS:

JACQUES DUÈZE, Cardinal in Curia, then Pope Jean XXII, aged 72.

FRANCESCO CAETANI, nephew of Pope Boniface VIII.

ARNAUD D’AUCH, Cardinal Camerlingo.

NAPOLÉON ORSINI, JACQUES and PIERRE COLONNA, BÉRENGER FRÉDOL, elder and younger brothers, ARNAUD DE PÉLAGRUE, STEFANESCHI, and MANDAGOUT, etc.

THE BARONS OF ARTOIS:

The Lords of VARENNES, SOUASTRE, CAUMONT, FIENNES, PICQUIGNY, KIÉREZ, HAUTPONLIEU, BEAUVAL, etc.

THE LOMBARDS:

SPINELLO TOLOMEI, a Siennese banker living in Paris.

GUCCIO BAGLIONI, his nephew, aged 20.

BOCCACCIO, a traveller, father of the poet Boccaccio.

THE CRESSAY FAMILY:

DAME ELIABEL, widow of the Lord of Cressay.

JEAN and PIERRE, her sons, aged 24 and 22 respectively.

MARIE, her daughter, aged 18.

ROBERT DE COURTENAY, Archbishop of Rheims.

GUILLAUME DE MELLO, Councillor to the Duke of Burgundy.

MESSIRE VARAY, Consul of Lyons.

GEOFFROY COQUATRIX, a Burgess of Paris, an army contractor.

MADAME DE BOUVILLE, wife of the one-time Chamberlain.

BÉATRICE D’HIRSON, niece of the Chancellor of Artois, Lady-in-Waiting to the Countess Mahaut.

All the above names have their place in history.

The Royal Succession

Queens wore white mourning.

The wimple of fine linen, enclosing her neck and imprisoning her chin to the lip, revealing only the centre of her face, was white; so was the great veil covering her forehead and eyebrows; so was the dress which, fastened at the wrists, reached to her feet. Queen Clémence of Hungary, widowed at twenty-three after ten months of marriage to King Louis X, had donned these almost conventual garments and would doubtless wear them for the rest of her life.

Prologue

IN THREE HUNDRED AND twenty-seven years, from the election of Hugues Capet to the death of Philip the Fair, only eleven Kings had reigned in France and each one had left a son to ascend the throne.

It was a prodigious dynasty, which Providence seemed to have marked out for duration and permanence. Only two of the eleven reigns had covered less than fifteen years.

This singular continuity in the exercise and transmission of power had allowed, if not determined, the formation of national unity.

For the feudal link, a purely personal one between vassal and suzerain, between the weaker and the stronger, was substituted gradually another relationship, another compact uniting the members of a vast human community which had for long been subject to similar vicissitudes and an identical law.

If the concept of the nation had not yet become evident, its symbol already existed in the person of the sovereign, the supreme source of authority and the ultimate court of appeal. Whoever thought of the King also thought of France.

And Philip the Fair, throughout his life, had set himself to cement this nascent unity with a powerful centralized administration and the systematic destruction of external and internal rivalry.

Hardly had the Iron King died, when his son, Louis X, followed him to the grave. The population could not help but see in these two deaths, kings struck down in their prime, one following so quickly on the other, the finger of fate.

Louis X, the Hutin, had reigned eighteen months, six days and ten hours. During this short period of time, this pitiful monarch had destroyed the greater part of his father’s achievement. His reign had seen the murder of his Queen and the hanging of his first minister; famine had ravaged France; two provinces had rebelled; and an army had been engulfed in the Flanders mud. The great nobles were infringing on the royal prerogatives once more; reaction was all-powerful; and the Treasury empty.

Louis X had ascended the throne at a moment when the world lacked a Pope; he died before a Pontiff had been elected, and Christendom trembled on the verge of schism.

And now France was without a king.

For Louis X, by his marriage to Marguerite of Burgundy, had left only a daughter of five years of age, Jeanne of Navarre, who was suspected strongly of bastardy. By his second marriage, he had bequeathed but an expectation: Queen Clémence was pregnant; but would not be brought to bed for five months. Moreover, it was being canvassed openly that the Hutin had been poisoned.

No disposition had been made for a regency; and personal ambitions resulted in individual attempts to seize power. In Paris the Count of Valois endeavoured to have himself proclaimed Regent. At Dijon the Duke of Burgundy, brother of the murdered Marguerite and the powerful head of a baronial league, undertook to avenge the memory of his sister by championing the rights of his niece. At Lyons the Count of Poitiers, elder surviving brother of the Hutin, was grappling with the intrigues of the Cardinals and vainly striving to force the Conclave to a decision. The Flemings were but awaiting the occasion to take up arms again; while the nobility of Artois was pertinaciously conducting a civil war.

All this was enough to remind the people of the curse pronounced two years before by the Grand Master of the Templars from among the faggots of his pyre. In that age of superstition, it might well have seemed, in the first week of June 1316, that the Capets were an accursed race.

1

The White Queen

QUEENS WORE white mourning.

The wimple of fine linen, enclosing her neck and imprisoning her chin to the lip, revealing only the centre of her face, was white; so was the great veil covering her forehead and eyebrows; so was the dress which, fastened at the wrists, reached to her feet. Queen Clémence of Hungary, widowed at twenty-three after ten months of marriage to King Louis X, had donned these almost conventual garments and would doubtless wear them for the rest of her life.

Henceforth no one would look on her wonderful golden hair, on the perfect oval of her face, and on the calm, lustrous splendour which had struck all beholders and made her beauty famous.

The narrow and pathetic mask, framed in its immaculate linen, bore the marks of sleepless nights and days of weeping. Even her gaze had altered, never coming to rest but seeming to flutter across the surface of people and of things. The lovely Queen Clémence already looked like the effigy on her tomb.

Nevertheless, beneath the folds of her dress, a new life was forming: Clémence was pregnant; and she was obsessed by the thought that her husband would never know his child.

‘If only Louis had lived long enough to see his child born!’ she thought. ‘Five months, only five months longer! How happy he would have been, particularly if it is a son. If I had only become pregnant on our wedding night!’

The Queen turned wearily to look at the Count of Valois, who was strutting up and down the room like a cock on a dunghill.

‘But why, Uncle, why should anyone have been so wicked as to poison him?’ she asked. ‘Did he not do all the good in his power? Why are you always searching for the wickedness of man where, doubtless, there is but a manifestation of the Divine Will?’

‘You are on this occasion alone in rendering to God that which seems rather to belong to the machinations of the Devil,’ replied Charles of Valois.

The great crest of his hood falling on his shoulder, his nose strong, his cheeks bloated and high of colour, his stomach thrust well to the fore, dressed in the same suit of black velvet with silver clasps which he had worn eighteen months earlier at the funeral of his brother Philip the Fair, Monseigneur of Valois had just returned from Saint-Denis, where he had been burying his nephew, Louis X. The ceremony had created a problem or two for him, because, for the first time since the ritual of royal burials had been established, the officers of the household, having cried: ‘The King is dead!’ had been unable to add: ‘Long live the King!’; and no one knew before whom the various rites, normally appropriate to the new sovereign, should be performed.

‘Very well! Break your wand before me,’ Valois had said to the Grand Chamberlain, Mathieu de Trye. ‘I am the eldest of the family and take precedence.’

But his half-brother, the Count of Evreux, had taken exception to this peculiar innovation, for Charles of Valois would certainly have taken advantage of it as an argument for his being recognized as Regent.

‘The eldest of the family, if you mean it in that sense,’ the Count of Evreux had said, ‘is not you, Charles. Our Uncle Robert of Clermont is the son of Saint Louis. Have you forgotten that he is still alive?’

‘You know very well that poor Robert is mad and that his clouded mind cannot be relied on in anything,’ Valois had replied, shrugging his shoulders.

In the end, after the funeral feast, which had been held in the abbey, the Grand Chamberlain had broken the insignia of his office before an empty chair.

‘Did not Louis give alms to the poor? Did he not pardon many prisoners?’ Clémence went on, as if she were trying to convince herself. ‘He had a generous heart, I assure you. If he sinned, he repented.’

It was clearly not the moment to contest the virtues with which the Queen embellished the recent memory of her husband. Nevertheless, Charles of Valois found it impossible to control an outburst of ill-humour.

‘I know, Niece, I know,’ he replied, ‘that you had a most pious influence on him, and that he was extremely generous … to you. But one cannot rule by Paternosters alone, nor by heaping presents on those one loves. Repentance is not enough to disarm the hatreds one has sown.’

‘So now,’ Clémence thought, ‘Charles, who laid a claim to power while Louis was alive, is denying him already. And soon I shall be reproached with all the presents he gave me. I have become the foreigner.’

She was too weak, too overcome to find the strength for indignation. She merely said: ‘I cannot believe that Louis was so hated that anyone would wish to kill him.’

‘All right, don’t believe it, Niece,’ cried Valois; ‘but it’s the fact! There’s the proof of the dog that licked the linen used for removing the entrails during the embalming and died an hour later. There’s …’

Clémence closed her eyes and clutched the arms of her chair in order not to reel at the vision it conjured up in her mind. How could anyone speak so cruelly of her husband, the King who had slept beside her, the father of the child she carried, compelling her to imagine the corpse beneath the knives of the embalmers?

Monseigneur of Valois continued to develop his macabre thesis. When would he stop talking, that fat, restless, vain authoritarian who, dressed sometimes in blue, sometimes in red, sometimes in black, had appeared at every important or tragic hour in Clémence’s life during the ten months she had been in France, to lecture her, deafen her with words and compel her to act against her will? Even on the morning of her marriage at Saint-Lyé, Uncle Valois, whom Clémence had scarcely ever seen, had almost spoiled the ceremony by instructing her in court intrigues of which she understood nothing. Clémence remembered Louis coming to meet her on the Troyes road, the country church, the room in the little castle, so hastily furnished as a nuptial chamber. ‘Did I realize my happiness? No, I must not weep in front of him,’ she thought.

‘Who the author of this appalling crime may be,’ went on Valois, ‘we do not yet know; but we shall discover him, Niece, I give you my solemn promise. If I am given the necessary powers, that is. We kings …’

Valois never lost an opportunity of reminding people of the fact that he had worn two crowns, which, though they were purely nominal, still put him on an equal footing with sovereign princes.1, fn1

‘We kings have enemies who are less hostile to our persons than to the decisions of our power; and there are many people who might have an interest in making you a widow. There are the Templars, whose Order, as I said at the time, it was a great mistake to suppress. They formed a secret conspiracy and swore to kill my brother and his sons. My brother is dead, his eldest son has followed him. There are the Roman Cardinals. Do you remember Cardinal Caetani’s attempt to cast a spell on Louis and your brother-in-law of Poitiers, both of whom he wished to destroy? The attempt was discovered, but Caetani may well have struck by other means. What do you expect? One cannot remove the Pope from the throne of Saint Peter, as my brother did, without arousing resentment. It is also possible that supporters of the Duke of Burgundy may still feel bitter about Marguerite’s punishment, to say nothing of the fact that you replaced her.’

Clémence looked Charles of Valois straight in the eye, which embarrassed him and made him flush a little. He had had some hand in Marguerite’s murder. He now realized that Clémence knew it; through Louis’s rash confidences no doubt.

But Clémence said nothing; it was a subject she was chary of broaching. She felt that she was involuntarily to blame. For her husband, whose virtues she boasted, had nevertheless had his first wife strangled so that he might marry her, Clémence, the niece of the King of Naples. Need one look further for the cause of God’s punishment?

‘And then there is your neighbour, the Countess Mahaut,’ Valois hurried on, ‘who is not the woman to shrink from crime, even the worst …’

‘How does she differ from you?’ thought Clémence, not daring to reply. ‘Nobody seems to shrink much from killing at this Court.’

‘And less than a month ago, to compel her to submit, Louis confiscated her county of Artois.’

For a moment Clémence wondered if Valois were not inventing all these possible culprits in order to conceal the fact that he was himself the author of the crime. But she was immediately horror-struck at the thought, for which there was indeed no possible basis. No, she refused to suspect anyone; she wanted Louis to have died a natural death. Nevertheless, Clémence gazed unconsciously out of the open window towards the south where, beyond the trees of the Forest of Vincennes, lay the Château of Conflans, Countess Mahaut’s summer residence. A few days before Louis’s death, Mahaut, accompanied by her daughter, the Countess of Poitiers, had paid Clémence a visit: an extremely polite visit. Clémence had not left them alone for a single instant. They had admired the tapestries in her room.

‘Nothing is more degrading than to imagine that there is a criminal among the people about one,’ thought Clémence, ‘and to start looking for treason in every face.’

‘That is why, my dear Niece,’ went on Valois, ‘you must return to Paris as I asked you. You know how fond of you I am. I arranged your marriage. Your father was my brother-in-law. Listen to me as you would have listened to him, had God spared him. The hand that struck down Louis may intend pursuing its vengeance on you and on the child you carry. I cannot leave you here, in the middle of the forest, at the mercy of the machinations of the wicked, and I shall be easy only when you are living close to me.’