Полная версия

The Mayfair Mystery: 2835 Mayfair

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain as 2835 Mayfair by Mitchell Kennerley 1907

Published as The Mayfair Mystery by The Detective Story Club Ltd

for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929

Introduction © David Brawn 2015

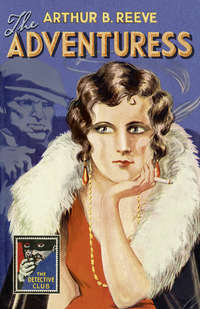

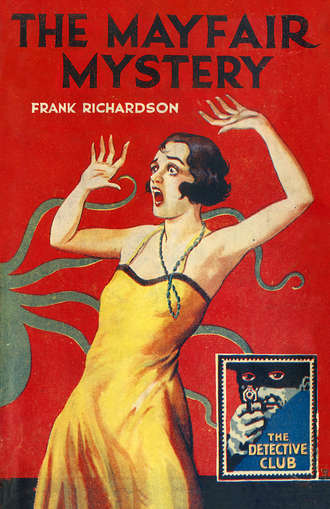

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2015

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137083

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780008137090

Version: 2015-07-06

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I: THE DEAD MAN

Chapter II: CONCERNING THE CORPSE

Chapter III: THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE CORPSE

Chapter IV: THE ALLEGED ADA

Chapter V: AT THE GRIDIRON

Chapter VI: THE TROUBLE WITH MINGEY

Chapter VII: MAINLY ABOUT LOVE

Chapter VIII: 2835 MAYFAIR

Chapter IX: 69 PEMBROKE STREET

Chapter X: THE MINGEY MYSTERY

Chapter XI: ‘PURE BROMPTON ROAD’

Chapter XII: AT THE CARLTON

Chapter XIII: A LITTLE DINNER

Chapter XIV: THE EVIDENCE OF NELLIE

Chapter XV: INSPECTOR JOHNSON

Chapter XVI: ‘UNCLE GUSSIE’

Chapter XVII: A PROPOSAL OF MARRIAGE

Chapter XVIII: JOHNSON AND BARLOW

Chapter XIX: THE DETECTIVES

Chapter XX: JOHNSON BECOMES BRIGHTER

Chapter XXI: NEWS OF SARAH

Chapter XXII: THE CURE FOR CANCER

Chapter XXIII: THE MYSTERIOUS BEHAVIOUR OF SIR CLIFFORD OAKLEIGH

Chapter XXIV: UNPOPULARITY

Chapter XXV: ‘I LOVE YOU’

Chapter XXVI: ‘UNCLE GUSSIE’ IS NONPLUSSED

Chapter XXVII: AT THE SAVOY

Chapter XXVIII: DISAPPOINTMENT

Chapter XXIX: REGGIE LOSES HIS JOB

Chapter XXX: AN UNFORTUNATE MEETING

Chapter XXXI: THE DISMISSAL OF MINGEY

Chapter XXXII: THE ASSISTANCE OF SMALLWOOD

Chapter XXXIII: MORPHIA?

Chapter XXXIV: A POSSIBLE CLUE

Chapter XXXV: HARDING MAKES HEADWAY

Chapter XXXVI: THE RETURN OF MIRIAM

Chapter XXXVII: THE ACCIDENT

Chapter XXXVIII: ‘SOMETHING IS ON HER MIND’

Chapter XXXIX: AN ASTOUNDING DISCOVERY

Chapter XL: MIRIAM’S DEFENCE

Chapter XLI: AT THE POLICE-COURT

Chapter XLII: THE SOLUTION

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. was celebrating exactly 100 years of book publishing when in the spring of 1919 Sir Godfrey Collins and his staff announced its first detective novel—The Skeleton Key by Bernard Capes. Capes, a prolific and versatile writer best known for his ghost stories, had delivered his manuscript to Collins shortly before falling prey to the worldwide flu pandemic in the autumn of 1918, and died before his most lucrative book in a 20-year writing career was published.

Sir Godfrey, who had served in the Victorian navy and later entered politics to become a Liberal M.P. and later Secretary of State for Scotland, had become head of publications at the Glasgow-based printing company in 1906 when his uncle, the ambitious and colourful William Collins III, plunged to an untimely death down an empty lift shaft in a freak accident at his Westminster flat. It is not known now whether Sir Godfrey had intended The Skeleton Key to be a one-off book or the start of a new initiative, but its immediate success coincided with a growing post-war interest in modern exciting fiction based on crime and mystery. Within ten years of The Skeleton Key, Collins had built up a rich stable of reliable and popular crime writers, among them Lynn Brock, J. S. Fletcher, Anthony Fielding, Herbert Adams, John Stephen Strange, Hulbert Footner, G. D. H. & M. Cole, J. Jefferson Farjeon, Vernon Loder, John Rhode, Francis D. Grierson, Miles Burton, Philip MacDonald, Freeman Wills Crofts and, in 1926, Agatha Christie.

Nearly all new novels in the early 1920s were hardback, usually costing 7/6 each, and the most popular titles were frequently rejacketed and reprinted in a ‘cheap edition’, still in hardcover but often smaller in size and always on cheaper paper. In fact, the idea of making cheap hardbacks out of popular copyright fiction by living authors (as opposed to nineteenth-century classics, as had been the convention) was one of Godfrey Collins’ earliest initiatives. His revolutionary ‘Books for the Million’ first went on sale in May 1907, but to Collins’ dismay rival publisher Thomas Nelson beat them into the shops with the same idea just three days earlier.

By 1928 Collins had pretty much cornered the market in this area with a rapidly growing number of different series, including Collins Classics, The Literary Press, The Novel Library, The London Book Co. and Westerns (later renamed The Wild West Club), with more than 2,500 cheap fiction titles now appearing in the Collins catalogue. It was probably therefore inevitable that Godfrey Collins would add another imprint to the growing range of sixpenny hardbacks: The Detective Story Club.

Launched in July 1929, the series included the whole panoply of crime writing: classic mystery novels from the previous century; tales of true crime; modern detective stories; and a growing publishing phenomenon, ‘the Book of the Film’, inspired by cinema’s new ‘talkies’. Twelve Detective Story Club books had been published by Christmas 1929, and another 60 or so would follow over the next five years. All had brand new colourful jacket designs with matching spines, finished off with the distinctive stamp of the masked ‘man with the gun’, an evolution of a sinister Zorro-like mask motif which had adorned 1920s Collins crime covers to distinguish them as detective novels.

Perhaps the boldest move was to change many of the book titles to make them sound more obvious: thus Bernard Capes’ The Skeleton Key became The Mystery of the Skeleton Key; Israel Zangwill’s The Big Bow Mystery—the first full-length ‘locked room’ novel—became The Perfect Crime; Maurice Drake’s obscure thriller WO2 was retitled The Mystery of the Mud Flats; and J. S. Le Fanu’s classic The Room in the Dragon Volant became The Flying Dragon. Perhaps the oddest alteration was to J. S. Fletcher’s accomplished short story collection The Ravenwood Mystery, renamed The Canterbury Mystery despite there being no such story in the book.

The Daily Mirror reviewed the new series: ‘Attractively bound in black and gold, with vivid coloured jackets, these books are bound to be immensely popular’, and an advertisement for the Detective Story Club in June 1930 claimed that it was ‘The Club with a Million Members!’ with already 19 books ‘sold by booksellers & newsagents everywhere’. The advert went on to state:

The extraordinary popularity of detective stories shows no signs of diminishing. The late Prime Minister [Stanley Baldwin] has confessed that he enjoys them; eminent men and women of every branch of life find them a mental stimulus. There is room for the Detective Story Club, Limited, founded to issue stories from the best detective writers—from Gaboriau to Edgar Wallace at a uniform price of 6d. Membership of the ‘club’ is completely informal. Any member of the public can buy these books through the ordinary trade channels, and in no other way.

The Detective Story Club was a big success. It spawned its own monthly short story magazine, which also sold for sixpence, and within a year gave Collins the confidence to launch a dedicated imprint for its full-price 7/6 hardbacks. In May 1930 the Crime Club was born, publishing three new mystery books every month, again selected by a body of ‘experts’. For its logo, the masked gunman evolved into a hooded gunman, and fans were invited to register by post for a free quarterly newsletter. The Crime Club ran until 1994 and published more than 2,000 titles, adding many new famous names to Collins’ existing roster, including Anthony Gilbert, Rex Stout, Ngaio Marsh, Elizabeth Ferrars, Joan Fleming, Robert Barnard, Julian Symons, H. R. F. Keating and Reginald Hill.

The Detective Story Club continued alongside the Crime Club until 1934, eventually abandoning the classics, the true crime and the film tie-ins and becoming principally a vehicle for cheap reprints of Collins’ earliest crime novels, such as 1920s titles by Agatha Christie, Freeman Wills Crofts and Philip MacDonald.

Then in 1935 the launch by publisher Allen Lane of his popular Penguin paperbacks sounded the death knell for the cheap hardback. Within a year, Collins launched its own paperback list, ‘White Circle Crime Club’, with stylish green and black covers showing a ghostlike gunman (and a knife-wielding accomplice), whose hood had now become a full-length shroud, and the original Man with the Gun was retired.

The resurrection of the Detective Story Club today is a chance to revisit some the best and most entertaining detective novels of the last century. The editors who picked titles for the Club chose well, although ideas about what constituted a detective story were obviously quite broad. Some books didn’t even feature detectives, and many of the rules and disciplines that characterised the era that has become known as the ‘Golden Age’ had yet to be formalised. These authors were the pioneers of an emerging genre—some broke new ground by inventing new types of story like the locked room mystery, the police procedural or the serial killer, while still drawing on more old-fashioned styles of classical romance, whimsical satire or the supernatural. But these were books with thrills and spills that got under the skin of their readers, and as such offer a candid glimpse today of how people thought and behaved at the time they were written.

The Mayfair Mystery, originally published in 1907 as 2835 Mayfair, is one such example. Author Frank Richardson had become very well known both in the UK and the USA as a satirist, his recurring theme a crusade against the Edwardian fashion for facial hair. He wrote more than a dozen books in just ten years, latterly collections of his widely published stories and parodies, including Bunkum (1907), its imaginatively titled sequel More Bunkum (1909), and perhaps his most famous, Whiskers and Soda (1910). These clearly endeared him to readers and reviewers on both sides of the Atlantic: ‘Whimsical, audacious, unconnected, and discursive, irresistibly amusing’ (Daily Express); ‘A master of extravaganza: No one can take up his books without being infected by the light, careless spirit which pervades them’ (Daily Telegraph); ‘No living writer knows better how to amuse than Mr Frank Richardson’ (New York Herald); ‘One of the wittiest men in London’ (New York Evening News); and so they went on.

Frank Collins Richardson was born in Paddington, Middlesex (as it was then) on 21 August 1870. He went to Marlborough College, where impending unpopularity amongst his peers from a ‘versatile incompetence’ at both games and work was seemingly averted by his ability to invent and tell vivid stories after lights out in the dormitory. After being ‘superannuated’ at Marlborough, he failed to get into Trinity, Oxford, where one Professor declaimed: ‘Richardson, you will always be a fool, but your sense of humour may prevent you from being a damned fool.’ However, he did get into Christ Church, but got out without a degree, and thanks to his father, the (inevitably bewhiskered) Chairman of the North Metropolitan Tramways Company, trained as a barrister and got work in all Courts, Parliamentary Bar, Chancery Bar, the Queen’s Bench and the Old Bailey.

A consistent failure, however, or so he maintained, Richardson took up playwriting, with moderate success, and a breakthrough with the publication of a couple of short stories led to him being invited to write novels. Choosing subjects he knew, but with a comedic twist, his first, The King’s Counsel, was published by Chatto and Windus in 1902, and three more followed in 1903, all with a strong vein of satire and gratuitous references to whiskers. Richardson is credited as coining the term ‘face-fungus’, and Punch called him ‘Mr Frank Whiskerson’. His ability to write caricatures also developed into drawing them, and his later books and articles often featured his own sketches.

Like so many clowns, however, Richardson’s life ended tragically. Widowed before he turned 40, his appetite for writing had all but dried up by the time he published a book of poetry, Shavings, in 1911. Although he may have exhausted his peculiar topic of humour, he had remained a popular figure, opening fêtes, signing books, drawing cartoons and judging seaside beauty contests. But on Thursday 2 August 1917, The Times announced his death, aged 46: ‘Mr Frank Collins Richardson, barrister, and novelist, was found dead in his chambers in Albemarle-Street, Piccadilly, yesterday. An inquest will be held.’ The next day, Westminster Coroner, Ingleby Oddie, heard evidence from Richardson’s sister and ex-valet which showed he had been suffering from depression and was given to ‘alcoholic excess’, despite his successful business interests as director of two flourishing companies: a cataract had robbed him of sight in one eye, and he feared it would spread and he would go blind. He had died on 31 July from a cut to his throat, and the jury returned a verdict of suicide whilst of unsound mind.

Published in the second batch of Detective Story Club titles in November 1929, The Mayfair Mystery was the only one of Frank Richardson’s books acquired by Collins for a reissue. Though none of his others were deemed suitable for the list, its predecessor, The Secret Kingdom (1906), set in the imaginary country of Numania, featured Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson in one of their earliest parodies, and might have been an interesting contender.

DAVID BRAWN

April 2015

CHAPTER I

THE DEAD MAN

THE body of a man in evening-dress lay on the dull, crimson carpet.

The black eyes were staring fixedly at the electric light hanging from copper shades. The jaw had dropped. The dead man’s face was remarkably handsome. The forehead was broad, and indicative of considerable intellectual power. Strongly-marked black eyebrows jutted perhaps a little too far over the aggressive, aquiline nose. The chin was strong and determined. The close-cut, shiny black hair was silvered at the sides. But for a slight, almost dandified moustache, one would have thought that the features were those of a barrister, of an ideal barrister.

The small room in which the corpse lay had evidently been newly decorated. A smell of varnish was in the air. It was furnished simply and in good taste. The walls were panelled in dark oak, and the few ornaments proved their owner to be a man of excellent judgment in matters of art. A few books, the latest novels, illustrated and scientific papers, lay on a Sheraton table. In the grate burnt a fire of ship’s logs, emitting a fragrant scent that battled with the smell of paint.

In Who’s Who? the dead man’s biography was as follows:

OAKLEIGH, Sir Clifford, First Baronet; created 1903. G.C.B., D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S. Physician-in-Ordinary to the Princess of Salmon von Gluckstein. Born 21st August 1870. Son of John Oakleigh of Aberdeen and Imogen B. Stapp of Chicago. Education: Eton, Christ Church, Oxford. First-class First Public Examination 1891; First Class Greats 1892; Edinburgh University, Gillespie Prizeman. Recreations: shooting, yachting and hypnotism. Address: 218 Harley Street. Clubs: Athenaeum, United Universities, Garrick, Beefsteak, Gridiron and Arthur’s.

CHAPTER II

CONCERNING THE CORPSE

‘THANK God, I’ve found you!’

As the servant closed the door, Reggie Pardell, in evening-dress, his flabby face pallid, almost ashen, sank into a chair.

George Harding rose hastily.

The K.C. looked down at the frightened figure in the chair, went into the dining-room, and returned with a brandy-and-soda.

‘Drink that,’ he said.

While Reggie drank with long gulps, his eyes stared at the gaunt barrister.

As he scanned the clear-cut, intellectual face, with its piercing grey eyes, its long, sinister, thin nose and tight-shut vigorous mouth, he felt a sensation of returning confidence. At the same time, also, there floated through his mind a feeling of irrelevant despair. Each was thirty-eight years of age. They had been at Christ Church together. George was a brilliant advocate and Reggie was—well, Reggie was an ex-black sheep. A passion for backing losers had been his undoing.

Harding took away the glass.

‘Feel better?’ he asked.

The other nodded.

‘What’s the trouble now?’

It was eleven o’clock, and from the library one could hear the sound of carriages and cabs passing along South Audley Street. In the home there was complete silence.

Reggie shook his head.

‘It’s not a trouble of mine this time, not directly. But it’s the most awful thing that’s ever happened. That’s why I’ve come to see you.’

Harding smiled. His friends always came to him in time of trouble. There was something in the man’s vigorous personality that invited sympathy; his vast reputation for acumen and knowledge of human life rendered him an invaluable adviser in moments of difficulty or danger.

He went back to his chair and lit a cigarette, waiting for his friend to speak.

The first words that came from Reggie’s lips were:

‘Clifford Oakleigh is dead.’

‘Dead!’ cried Harding, aghast at the news that his best friend at Eton and Oxford, and indeed in the world, had died. Horrified, he pressed for particulars.

‘When did he die? How do you know?’

‘I have just come from his house.’

‘From Harley Street?’

‘He doesn’t use that as a house.’

‘I know. He lives at Claridge’s.’ The K.C. corrected himself.

Reggie shook his head.

‘He has lately taken, or rather built, a little house in King Street, Mayfair; just near here. Didn’t he tell you?’

‘Never a word.’

‘Well, he only moved in a week ago.’

‘But what were you doing there? I thought that you and he were not quite…’

‘No,’ said Reggie, grimly. ‘But he has been very good to me one way and another. He has lent me a lot of money; I wouldn’t have gone to him again, but…the fact is I’m his valet.’

The barrister gazed at him in surprise.

‘I was his valet,’ repeated Reggie. ‘He engaged me as a valet.’

‘You were his valet?’

Harding stared at the prematurely fat young man with three pendulous chins and an unbecomingly large waist. It seemed incredible to him that Sir Clifford Oakleigh, one of the most famous physicians of his day, one of the most brilliant men of all time, had selected that mountain of adiposity as his valet. Further, it struck him as extraordinary that a man like Reggie Pardell, a scion of one of the oldest families in England, should be willing to perform these duties.

Reggie explained.

‘You see it was like this, George…Harding. I was absolutely stony. Of course, I’d got clothes, and the run of my teeth, and so on. But I was broke to the world. Poor Clifford met me one day at Arthur’s and he guessed how things were. He made me a sporting offer. He said: “Look here, old chap, you have failed at most things. The only thing you do understand is clothes. Come and be my valet. I will give you £500 a year.” At first, I thought he was joking. But he wasn’t, and he installed me in this little box of his in King Street. Only part of the house is furnished; his sitting-room and bedroom and my bedroom. He never has his meals there. The charwoman comes in every day and sees to the place; all I had to do was to look after his clothes. It really was the most extraordinary arrangement that I’ve ever come across. It was philanthropy on poor old Clifford’s part, because my time was entirely my own.’

The other reflected.

‘It’s strange he never told me about this.’

‘Dear old Clifford wouldn’t,’ rejoined Reggie.

‘You see, he knew that I shouldn’t like it to be known that I was doing a bit of valeting. Well, after all, what’s the disgrace? My elder brother, Horace, is chaperoning the “Venus” at the Nasallheimers’ Gallery in Bond Street. It is his duty to show financiers and peers and people of that sort the beauties of Titian. Of course, if he ever succeeds in selling it, he will lose his job as vestal virgin to the “Venus”. And my cousin, Dartmouth, keeps body and soul and motor together by selling Stereoscopic Co. et Fils Cuvée Anonyme to unwilling aristocrats. Still, Clifford knew that I shouldn’t like people to hear that I was his valet.’

The lawyer’s knowledge of Reggie’s character told him that interruption would be useless. He must tell his story in his own way. He merely showed his impatience by taking out his watch and clicking it.

‘I know,’ said Reggie, accepting the hint.

‘Well, tonight I dined with three pals at White’s. We were going on to the Covent Garden Ball. But, somehow, an extra man turned up and someone suggested Bridge. You know I’ve not got a very good reputation for solvency, and I could see they’d be just as well pleased if I didn’t cut in, so at ten o’clock I left them. I thought at first of going on to the ball alone. But that struck me as being a dull scheme, and so I walked back to King Street.’