Полная версия

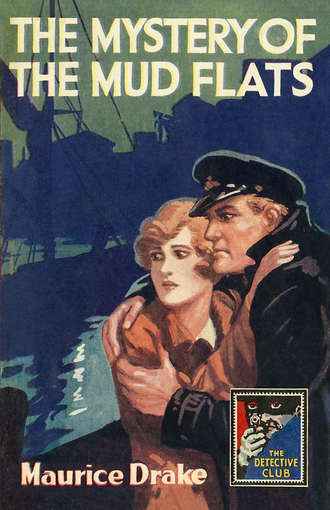

The Mystery of the Mud Flats

‘Ask him,’ I suggested, and Voogdt did so. I fancy he told him my bookshelf was the principal attraction aft. ’Kiah displayed no wounded feelings whatever and Voogdt’s thought for him only rendered him the more welcome in my quarters; so it was a very merry and bright ship’s company that entered the Scheldt the fourth morning after leaving Devonshire.

The Deutsche-West-Inde boats used to call at Antwerp, so I’d been in and out of the river often enough before. Terneuzen lies on the south bank, at the entrance to the Ghent ship canal, about a couple of miles from the mouth of the river, and as tide was making we managed to get there without a pilot. It seemed to me a queer place for an English company to open shop, yet there were the sheds, plain enough to see with ‘Isle of Axel Trading Company’ painted upon them as large as life. They were built on the big embankment that keeps the tide off the fields, a good mile from the town and lock-gates, flat Dutch pastures and tillage all around them, and I never saw a place that looked less like business in all my life. Four small sheds of wood and corrugated iron sufficed for office and warehouses, and a chimney smoking behind the office hinted at some sort of dwelling under the same roof. The wharf was a mere skeleton of wooden piles sticking out into the water, with a six-foot planked way along the top leading to the sheds. According to the chart, the whole lot, houses and wharf, would be half-a-mile from the river at low water, and separated from the stream by dreary mud-flats. It was just high tide when we got there, and so were able to float alongside the wharf, a red-faced youngish man with short curly hair shouting directions from the shore. We rode so high that we could look over the embankment right down on the cows feeding in the green pastures behind it. The place was as peaceful as a dairy farm, no houses nearer than the town, and I wondered more than ever what trade any company could do in such a deserted spot. As soon as we were made fast the curly-haired man came aboard, very busy about nothing.

‘My name’s Cheyne. I’m the manager. Capt’n West? With clay from Teignmouth?’

‘Forty tons,’ I said.

‘Good. May as well get your hatch cover off, Capt’n. Then come ashore’n have a drink. We’ll get it out of her tomorrow, ’n then ballast you to rights, ’n off to sea again, eh? Too long in port’s bad f’r th’ morals, eh?’

‘Shouldn’t think there was much chance of going on the bend here,’ I said. ‘Unless you go bird-nesting or chasing cows.’

‘Y’ can go on the bend anywhere, cocky,’ he said, and hiccupped, and I noticed he’d managed it all right. ‘Terneuzen’s a hot little shop, lemme tell you. ’T least I’ve livened ’em up a bit. Sleepy hole it was before they had me t’ liven ’em up. We’ll go into town this evening an’ shake a leg, what?’

I took my papers to his office—the untidiest hole I was ever in—sat among the litter for half-an-hour, had a drink and a chat, and then went aboard again.

Voogdt was stowing the foresail when I got back and looked at me inquiringly.

‘That cove full?’ he asked.

‘Full as an egg. Useful sort of manager, eh?’

‘Useful sort of business generally, I should say,’ he replied. ‘What the dickens are they going to do with this clay here? Feed cows on it? Is your money all right, skipper?’

‘I haven’t earned my advance of fifty yet. When I have, I’ll ask for another.’

‘I should, if I were you,’ said he, and then the matter dropped.

However, there were more signs of activity next morning. We rigged a rubbish wheel at the gaff-end, and with the help of four hired Dutch labourers started to get the clay ashore. Even Cheyne put on an old suit of clothes and bore a hand, but I never saw such slack methods as his in my life. The man worked like a navvy, I grant, but I should have thought he’d have been better employed in tallying the tubs of clay. As it was, he’d pull and haul with the rest of us, very noisy and hearty, and I admit he hustled those slow-bellied Dutchmen better than I could, knowing the language as he did. Then, when we’d got out a half-dozen or dozen tubs, he’d pick up his tally-book again.

‘How many’s that?’ he’d cry.

‘I make it a hundred and twenty-three.’

‘Hundred and twenty-three goes,’ he’d say, and tick them off without checking my figures, and then back to the tackles he’d go again. I put him down as unmethodical but a man-driver; and the driving was wanted no denying that, for those four Dutchmen might have been picked for their stupidity. In fact, two of them were no better than sheer imbeciles.

When we came to the bottom of the forty tons Cheyne began to get fussy. He was as careful to have the last pound or two of clay out of her as he’d been careless about the two-hundredweight tubs. He even had the tubs and buckets scraped and the sides of the hold cleaned down as though he wanted to make up for his slackness in the tallying. It was high water again by the time we had done and he said we could knock off till half-ebb.

‘Your chaps had better turn in for a spell,’ he told me. ‘We work at low water after this. I’m going up town now to get some grub. Care to join me, Capt’n? Yes? Come along, then.’

On the way he explained how he wanted us to ballast. ‘That mud you’re lying on is always silting up and we ballast with that to keep the channel open to the wharf. See?’

‘How are we to get it aboard?’

‘By brute force and bally ignorance, my son; same’s we got the clay out with. We can’t afford a dredger yet. All you have to do is to lower the tubs on the side away from the wharf, send two or three men overside with shovels, and the rest pullihaul, and there you are. How much d’ye want to steady that packet of yours?’

‘Twelve tons’ll be ample, this weather.’

‘Take twenty—take twenty,’ said he. ‘You never know when it may come on to blow off this coast. Besides, we want the stuff taken away, and it’s a charity to give those Dutch lumps another day’s work. Bright lot, ain’t they?’

As we walked along the top of the embankment I couldn’t help wondering where he was taking me, for not a sign of any town or village could, I see. On our left was the river, shallow water over mud-flats, broken here and there by a red or white iron beacon pole marking the channel to the entrance to the canal; on our right flat pastures divided by long lines of poplars, receding in perspective to the flat horizon. Dominating them, the great ship canal ran inland, its high banks planted with avenues of lime-trees, and, save for a block of buildings at its entrance, behind which rose a little church spire, not a house was to be seen.

Once we crossed the lock-gates the town, such as it was, became visible lying low in the farther angle formed by the embankment of the canal and river frontage. It proved to be the usual ’longshore Dutch village, half nautical, half pastoral: two or three tiny streets of one or two storeyed houses, red tiled, gay with green and white paint, and clean as rows of new pins. They clustered round the foot of the grey church tower, church and cottages alike dwarfed to toys by the great locks of the canal. The block of buildings I had seen proved to be a modern hotel, pleasantly placed for summer trade with wooden benches outside it under the lime-trees, a pilot-house, built of little Dutch bricks and looking for all the world like a doll’s house, and a tobacco shop, clean as a dairy, much patronised by the sailors passing through the locks. I never saw a quainter, prettier little place—a sleepy little farming village, with the canal alongside to smoke your pipe by, and watch the passing ships. The girls are pretty there too: big-eyed, pale and dark, which is not what one expects to find in Holland. The head-dress of the district is a wide-winged thing of white linen like a Beguine nun’s, and instead of the usual golden cups to hide their ears, the women wear thin fluttering plates of gold on either side of their forehead, which flip about and tinkle like golden butterflies. Under the summer evening light, I took to the place at once.

Contrary to all Cheyne’s talk of bad business and economy, he wasn’t mean about his personal expenditure. He stood me a thundering good dinner in the hotel, and a first-rate bottle of hock with it, and as many cigars as I could smoke. But somehow I couldn’t take to the man. He let on to be a square, hearty chap enough with no nonsense about him, but his manner was too uncertain for me. One minute he was over-effusive, slap-on-the-back, hail-fellow-well-met, and the next was standoffish, as though he’d remembered he was one of my employers and wanted to remind me of it too. He wasn’t as good a man as Ward, but he didn’t think so, and made no secret of his opinion.

‘Oh, Leonard’s all right,’ he said once, when I was telling him how I’d been chartered. ‘He’s all right enough, but he’s a squaretoes. I wonder he gave you a job, if you had on a brass hat when he first met you.’ Another time he said he was a fossil. ‘He’s too slow to come in out of a shower, is ol’ Len. Good job for him I’m here. He’d be robbed right and left else.’

He was ready enough to talk about himself. He’d been a sailor, too, it seemed. ‘With Warbeck’s, of Sunderland,’ he said, with an air, as though he expected a lowly coasting skipper like me to grovel at the very name of his tinpot firm. ‘I was third officer on their Gloucester.’

‘A fine boat that,’ I said, and let him gas about her for a while.

Later on I tried to sound him about the two girls, but all I could get out of him was that the Pamily one was his cousin, and the other—a Miss Lavington—was her cousin on the other side.’

His business talk varied between over-confidence and sudden reticence or evasions of the point under discussion. He gave me the notion, somehow, that he was rather incapable, but was trying hard to impress one with his wits and ability. If he’d been altogether reserved, I should have liked him better. It was none of my business, the way he conducted the company’s affairs; but his half-chummy, half-patronising way made me tired, and I was glad to get back and start ballasting the Luck and Charity.

The wet mud was stiff, awful stuff to shovel and worse to stand on. We put some planks on it to give foothold, but we were slipping about all the time, and in half an hour all hands were slime from head to foot. Voogdt chucked it. ‘I can’t shovel this stuff,’ he said. ‘It’s man’s work, and I’m only half-a-man. Am I sacked, skipper?’

‘Not you,’ I said. ‘Get aboard and find something to do on deck. This job ’ud kill a horse.’

Cheyne came down soon after in dirty clothes with a shovel, and asked what ‘that chap’ was doing aboard. He grumbled a little when I told him Voogdt couldn’t do heavy work. ‘This is an all-hands job. If I can take a shovel, he ought to.’

‘He can’t,’ I said, ‘and that’s all there is about it,’ and Cheyne said no more.

I’m bound to say he worked like a good one himself: by my reckoning we got a hundred and twenty tubs aboard in three hours. That made a good twelve tons and when the tide drove us off the mud I told him we were ready for sea.

‘No hurry,’ said he. ‘I haven’t got your sailing orders yet. Turn your chaps in for a spell, and we’ll get a few more tubs aboard next ebb.’

Next ebb wasn’t till midnight, and I told him so.

‘Can’t your tender babes work after dark?’ he sneered.

‘They’ll work when I tell ’em,’ I said rather hotly, for his tone annoyed me.

‘Then tell ’em now,’ he said. ‘Tell ’em it’s pay and a quarter for night work, if you like. I’ve got plenty of lanterns in the shed.’

Who could make anything of such ways? Employing fools because they were cheap, and paying able seamen pay and a quarter to help them! Extra pay for night work at putting more ballast in a boat than she needed, because he wanted mud cleared away! A dredger would have cleared the lot in a couple of days. I thought of Voogdt’s warning, and decided I might as well see if I could get another advance. I’d spent thirty pounds in fitting out and victualling, and clothes and things for the three of us, but that left me nearly twenty in hand, and of the money spent certainly ten or twelve pounds had been unauthorised expenditure on our personal needs. On the other hand, the freight worked out at about thirty pounds, so that really I still owed the company the twenty I had left. However, when I asked for an advance, Cheyne made no bones about granting it. ‘How much?’ was all he said.

I hung in the wind a minute, uncertain what to ask. ‘I spent thirty fitting out,’ I said, ‘and the freight’s thirty. Would another twenty be too much?’

‘Say thirty, to be on the safe side,’ said he. ‘The Oost-Nederland Bank in Terneuzen’ll cash my cheque for you,’ and he drew me a cheque on the spot. This after his harping on economy and grumbling about Voogdt being idle! I concluded finally that he was an unbusinesslike fool.

As I was leaving the office he called after me. ‘We’re paying two bob ballast allowance,’ said he.

‘Two bob?’ I was ashamed to confess my ignorance of what he meant by ballast allowance.

‘Two bob a ton. So it’s worth your while to ballast pretty deep. Two quid in your pockets if you take away twenty tons, and only four and twenty bob if you go as you are. So you’ll see it pays you to wait a tide.’

‘It would pay me to fill her full, then,’ I said, surprised.

‘A sure thing it would. But of course that’s nonsense. Twenty tons is ample, as you say. Take twenty-five if you’ve got time; but you must get away next tide. I’m expecting the Olive Leaf tomorrow from Grangemouth, and there’s no room at the wharf for the two of you.’

When I got aboard after cashing the cheque Voogdt was standing by the hatch looking at the heaps of slimy muck in the hold. I jingled the canvas bag in his face.

‘Did you touch him?’ he asked.

‘For thirty. So we’re still a quid or two ahead of ’em.’

‘What d’ye make of the man?’ he asked, jerking his head towards the office.

‘A bumptious, silly fool. That’s what I make of him.’

‘What was the man Ward like? Another fool?’

‘Not he,’ I said. ‘Unbusinesslike he may be, but a fool he is not, if I’m any judge. I hope this chap isn’t going to let him down.’

‘So he isn’t going to let you down, that don’t matter much,’ Voogdt grunted. ‘When are we going to get hatches on?’

‘Next tide. There’s some more ballast to come aboard first.’

‘What on earth d’you want more ballast for?’

‘I don’t want it,’ I said. ‘At least the boat doesn’t. But there’s two bob a ton allowance on all we take away it seems.’

‘That’s a rum notion, paying on ballast, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I’ve only been in steam since I served my apprenticeship. Come to think of it, I’ve never carried ballast before. Even when I was serving my apprenticeship in sail we always had freights both ways. I suppose ballast allowance is a custom in this coasting trade.’

‘A rum custom,’ said Voogdt. ‘Tempting skippers to strain their vessels with useless stuff. And seems to me I’ve heard of paying for ballast before now.’

‘Well, that’s possible,’ I said. ‘P’raps the ship that left just before had a good ballast allowance and swept the quay clean. Besides, they want this stuff cleared away.’

‘Ah! That explains it,’ said he. ‘Why didn’t you say so before? How d’ye expect to make a sailorman of me if you don’t instruct me as we go along?’

We worked that night by the light of hand-lanterns, but all hands were tired out, and though I promised ’Kiah and Voogdt to share the new allowance equally, we couldn’t get more than about ten tons aboard. Cheyne said that would do. ‘It’ll have to. The Olive Leaf ’ll be here next thing. You can charge for twenty-three tons, Capt’n. That do you? Here’s your papers. You’re for Dartmouth, to load deals. Now get your hatch cover on, and slip it with the morning tide.’

It came on to blow a little when we got outside. Nothing to hurt; a northerly breeze, too, which was all in our favour, but we had a bit of bucketing in the Straits of Dover. The Luck and Charity I knew I could rely on; with her extra ballast she was as stiff as a church, and I felt a bit more amiable towards Cheyne when I saw how well she behaved. We got wet jackets, of course, but nothing worse. ’Kiah I’d tried before and could trust, too, but Voogdt and the running-gear were new, and I watched them both. The man shaped as well as the hemp and manilla: both were inclined to give a bit under the strain at first, but a brace now and then to the tackle and a helping hand and a joke with the man did wonders. Both, were working sweetly before we reached the Race of Portland, and Voogdt took us through it, only laughing whenever some nasty cross-sea slopped aboard and slatted down over him. It was pretty to see him, the veins standing out like twisted wire on his wet, lean hands as he strained to steady the kicking wheel, and to think how scared he’d looked when he came on deck two days before and found me driving through it with the lee rail under water and the hatch cover awash. Working like a Trojan, laughing at the smashing of our bows and the cataracts the Race was sending over him, he didn’t look much like an indoor man with his death warrant signed, sealed and delivered by the doctors.

‘Gad! This is fine!’ he cried, when I went to give him a hand. ‘No, let me go, skipper. I can take her through it myself. I like it.’

He was able to bear a hand in Dartmouth now, when it came to loading the deals. In fact I think he handled more of them than did the quay-lumpers, who were half asleep, like all Devonshire men. Good food and a regular life were telling on him; he was putting on flesh, and the sea air was beginning to colour his sallow sunburnt cheeks a bit.

We got our ballast out on the quay, and the deals aboard in four days, but then had to wait a day or two, the wind having shifted round to the east. Voogdt spent his time idling about the old town, and ’Kiah had a half-day’s holiday and went to Topsham. I was sitting on deck smoking and thinking about the spree I’d had at last Dartmouth regatta when somebody hailed from close alongside.

‘Luck and Charity ahoy!’

‘Ahoy!’ I answered, and jumped up to see who it was. I don’t think I was ever more staggered in my life, for there in a waterman’s boat just under our stern was the Pamily girl!

I threw a rope ladder overside and she scrambled aboard, and I stood staring at her, with my mouth open, I expect.

‘Good afternoon,’ she said shortly. ‘You’re loaded, I see.’

‘Y-yes,’ I stammered. ‘We got away from the wharf yesterday afternoon.’

‘I’ll see your papers,’ she said, most businesslike, and turned to the man in the boat. ‘You’ll wait for me, please,’ and she led the way to the cabin.

Dumb with surprise, I got the papers out and laid them on the table before her. She went through them all, her brows knitted, for all the world like a young housewife trying to check the butcher’s bill. I couldn’t believe she knew anything about the business, but she made no remarks, only folding each paper as she read it and handing back the lot when she’d done.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘You brought ballast, didn’t you? How much?’ Twenty-three tons, Mr Cheyne made it,’ I told her.

‘Where is it?’

‘On the ballast quay.’

‘Thank you. That’s all I want.’ She got up, and looked me up and down. ‘You’re looking very well,’ she said.

‘I’m very fit, thanks. Regular employment and—and all that sort of thing, you know.’

She nodded and went on deck, and I followed her. Just as she was going down into her boat I asked her if I could offer her a cup of tea.

For one minute I thought there was going to be more face-smacking, but she suddenly turned dangerously pleasant.

‘I should love it,’ she gushed. ‘But I mustn’t stay long, Captain West. Miss Lavington’s waiting for me ashore.’

‘It won’t take any time,’ I assured her. ‘I’ve got one of those oil blast-lamps that boil a kettle in about five minutes.’

She let me get tea and we drank it on deck, and all the time I felt like one sitting on a powder magazine. Her manner was atrociously correct—demure and sweetie-sweetie, prunes and prisms all the time; and she was making eyes at me most affectedly with every word. But I thought I could read behind that; I guessed she was trying to lure me out into the open and destroy me, and I wasn’t taking any. I was a coasting skipper; she the friend and, in a sense, the representative of my employers. So the more she gushed the politer I got, and when she rowed away I swear she was biting her lip. That sort of sexless little guttersnipe just loves a row, and she didn’t bring it off that time.

Voogdt hailed me from the quay soon after, and I went to fetch him in the dinghy. He had learnt that the deals we had shipped were from the Baltic and fell to discussing the matter with me.

‘More paying trade for our employers,’ he said. ‘Shipping deals from the Baltic to Terneuzen via Dartmouth. You note the direct and economical route, skipper?’

‘Oh, hang the company!’ I said. ‘If they’re going scat, they’re going scat. Meanwhile we’re being paid to learn the coasting trade.’

‘It’ll take a bit of learning, I can see,’ said Voogdt dryly. ‘I hope it won’t be too much for my poor brain.’ And not another word could I get out of him. ’Kiah came back that night, silent as ever, and next day the wind went south with the sun and we got under way for Terneuzen again.

CHAPTER IV

CONCERNING A CARGO OF POTATOES

VOOGDT worried me with questions about the cargo all the way up Channel, and for the life of me I couldn’t find an answer for him that even satisfied myself. Here were we being paid on the tonnage of the boat—sixty tons burthen—and only carrying thirty. Last voyage it had been forty, so that in two voyages we were drawing money for fifty tons of cargo which we had never shipped. For the sake of argument I put it that their customer might only have ordered forty tons of clay, and as to the deals, they were ugly stowage for a boat as small as the Luck and Charity. Anyhow, I didn’t see why we should worry so long as our charter money was paid.

His words had stirred my curiosity a little by this time, and when we reached Terneuzen my first care was to see whether any of our clay was left over from the last voyage. It was all gone, however, and I nudged Voogdt, drawing his attention to the fact. In its place was a large heap of broken stone. He looked at it, rubbing his bearded chin in meditation.

‘What’s that stuff for?’ he asked.

‘How should I know?’ I said impatiently. ‘To feed cows on, I suppose.’

‘Looks like road metal to me,’ he said musingly, and sure enough when Cheyne came aboard he told me that was what it was.

‘It came as ballast,’ he condescended to explain. ‘We can use it very well. Some of it’ll stiffen the mud behind the wharf and the rest mend the cart-track between here and the town.’

I told Voogdt this and he nodded. ‘So the Olive Leaf brought ballast, did she? I wonder what she took away?’

By the evening I was able to tell him that too. Cheyne asked me to dinner, as before, and casually mentioned her at the table as having gone farther up river.

‘To Antwerp?’ I asked.

‘Yes. She took up some of your clay. It was sold to Ghent, but the buyers sold again to an Antwerp pottery.’

I didn’t question him farther, but chuckled rather as I thought what a mare’s nest Voogdt would find in that announcement. Cheyne saw my smile and without more reason fired up in a moment.

‘What the—do you see to grin at in that?’ he demanded. ‘Don’t you believe me?’

‘Of course I do,’ I asid, surprised. ‘I wasn’t laughing at anything you said.’

For a moment he looked threatening, then calmed down and passed the bottle along.

In the intervals of getting out the deals, I told Voogdt where the clay had gone, but he displayed no surprise.

Ballasting was done the same way as before, except that Voogdt was able to help part of the time, and we sailed with a full twenty-five tons of mud instead of a bare twenty-three. As before, Cheyne was in a hurry to get rid of us at the last.