Полная версия

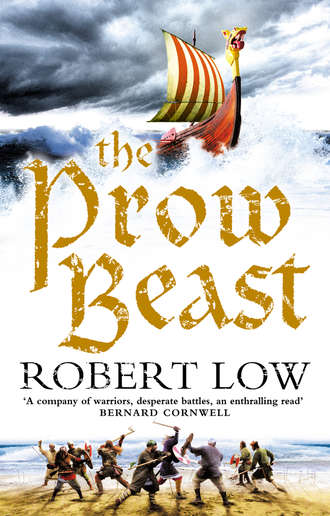

The Prow Beast

‘That’s a cargo I could do without,’ I answered without thinking, then caught his jaundiced eye. We both smiled, though it was grim – then I noticed the girl at the back. I had taken her for a thrall, in her shapeless, colourless dress, kerchief over what I took to be a shaved head, but she walked like she had gold between her legs. Thin and small, with a face too big for her and eyes dark and liquid as the black fjord.

‘She is a Mazur,’ Jarl Brand said, following my gaze. ‘Her name turns out in Slav to be Chernoglazov – Dark Eye – but the queen and her fat cow call her Drozdov, Blackbird.’

‘A thrall?’ I asked uncertainly and he shook his head.

‘I was thinking that, too, when I saw her first,’ he replied with a grunt of humour, ‘but it is worse than that – she is a hostage, daughter of a chief of one of the tribes that Mieczyslaw the Pol wants to control to the east of him. She is proud as a queen, all the same, and worships some three-headed god. Or four, I am never sure.’

I looked at the bird-named woman – well, girl, in truth. A long way from home to keep her from being snatched back, held as surety for her tribe’s good behaviour, she had a look half-way between scorn and a deer at the point of running. Truly, a cargo I would not wish to be carrying myself and did not relish it washing up on my beach.

However, it had an unexpected side to it; Thorgunna, presented with the honour of a queen and a jarl’s fostri in her house, beamed with pleasure at Jarl Brand and me both, as if we had personally arranged for it. Brand saw it and patted my shoulder soothingly, smiling stiffly the while.

‘This will change,’ he noted, ‘when Sigrith shows how a queen expects to be treated.’

His men unloaded food and drink, which was welcomed and we feasted everyone on coal-roasted horse, lamb, fine fish and good bread – though Sigrith turned her nose up at such fare, whether from sickness or disgust, and Thorgunna shot me the first of many meaningful glances across the hall and fell to muttering with her sister.

Since the women were full of bairns, one way and another, they sat and talked weans with the proud Sigrith, leaving Finn and Botolf and me with Jarl Brand and his serious-faced son, Koll.

The boy, ice-white as his da, sat stiffly at what must have been a trial for one so young – sent to the strange world of the Oathsworn’s jarl, ripped from his ma’s cooing, yet still eager to please. He sat, considered and careful over all he did, so as not to make a mistake and shame his father. At one and the same time it warmed and broke your heart.

There was no point in trying to talk the stiff out of him – for one thing the hall roared and fretted with feasting, so that you had to shout; it is a hard thing to be considerate and consoling when you are bellowing. For another, he was gripped with fear and saw me only as the huge stranger he was to be left with and took no comfort in that.

In the end, Thorgunna and Botolf’s Ingrid swept him up and into the comfort of their mothering, which brought such relief to his face that, in the end, he managed a laugh or two. For his part, Jarl Brand smiled and drank and ate as if he did not have a care, but he had come here to leave me the boy and, like all fathers, was agonising over it even as he saw the need.

Leo the monk had seen all this, too, which did not surprise me. A scribbler of histories, he had told me earlier, wanting to know tales of the siege at Sarkel and the fight at Antioch from one who had been at both. Aye, he was young and smiling and seal-sleek, that one – but I had dealt with Great City merchants and I knew these Greek-Romans well, oiled beards and flattery both.

‘I never understood about fostering,’ Leo said, leaning forward to speak quietly to me, while Brand and Finn argued over, of all things, the best way to season new lamb; Brand kept shooting his son sideways glances, making sure he was not too afraid. ‘It is not, as it is with us in Constantinople, a polite way of taking hostages.’

He regarded me with his olive-stone eyes and his too-ready smile, while I sought words to explain what a fostri was.

‘Jarl Brand does me honour,’ I told him. ‘To be offered the rearing of a child to manhood is no light thing and usually not done outside the aett.’

‘The…aett?’

‘Clan. Family. House,’ I answered in Greek and he nodded, picking at bread with the long fingers of one hand, stained black-brown from ink.

‘So he has welcomed you into his house,’ Leo declared, chewing with grimaces at the grit he found. ‘Not, I surmise, as an equal.’

It was true, of course – accepting the fostering of another’s child was also an acceptance that the father was of a higher standing than you were. But this bothered me much less than the fact that Leo, the innocent monk from the Great City and barely out of his teens, had worked this out. Even then, with only a little more than twenty years on him, he had a mind of whirling cogs and toothed wheels, like those I had seen once driving mills and waterwheels in Serkland.

He also ate the horse, spearing greasy slivers of it on a little two-tined eating fork. This surprised me, for Christ followers considered that to be a pagan ritual and would not usually do it. He saw me follow the food to his mouth and knew what I was thinking, smiling and shrugging as he chewed.

‘I shall do penance for this later. The one thing you learn swiftly about being a diplomat is not to offend.’

‘Or suffer for being a Christ priest in a land of Odin,’ interrupted Jarl Brand, subtle as a forge hammer. ‘This is Hestreng, home of the Oathsworn, Odin’s own favourites. Christ followers find no soil for their seed here, eh, Orm?

‘Bone, blood and steel,’ he added when I said nothing. The words were from the Odin Oath that bound what was left of my varjazi, my band of brothers; it made Leo raise his eyebrows, turning his eyes round and wide as if alarmed.

‘I did not think I was in such danger. Am I, then, to be nailed to a tree?’

I thought about that carefully. The shaven-headed priests of the Christ could come and go as they pleased around Hestreng and say what they chose, provided they caused no trouble. Sometimes, though, the people grew tired of being ranted at and chased them away with blows. Down in the south, I had heard, the skin-wearing trolls of the Going folk took hold of an irritating one now and then and sacrificed him in the old way, nailed to a tree in honour of Odin. That Leo knew of this also meant he was not fresh from a cloister.

‘I heard tales from travellers,’ he replied, seeing me study him and looking back at me with his flat, wide-eyed gaze while he lied. ‘Of course, those unfortunate monks were Franks and Saxlanders and, though brothers in Christ – give or take an argument or two – lacking somewhat in diplomacy.’

‘And weaponry,’ I added and we locked eyes for a moment, like rutting elks. At the end, I felt sure there was as much steel hidden about this singular monk as there was running down his spine. I did not like him one bit and trusted him even less.

Now I had been shown the warp and weft of matters there was nothing left but to nod and smile while Cormac, Aoife’s son, filled our horns. Jarl Brand frowned at the sight of him, as he always did, since the boy was as colourless as the jarl himself. White to his eyelashes, he was, with eyes of the palest blue, and it was not hard to see which tree the twig had sprouted from. When Cormac filled little Koll’s horn with watered ale, their heads almost touching, I heard Brand suck in air sharply.

‘The boy is growing,’ he muttered. ‘I must do something about him…’

‘He needs a father, that one,’ I added meaningfully and he nodded, then smiled fondly at Koll. Aoife went by, filling horns and swaying her hips just a little more, I was thinking, so that Jarl Brand grunted and stirred on his bench.

I sighed; after some nights here, the chances were strong that, this time next year, we would have another bone-haired yelper from Aoife, another ice-white bairn. As if we did not have little eagles enough at the flight’s edge…

In the morning, buds unfolded in green mists, sunlight sparkled wetly on grass and spring sauntered across the land while the Oathsworn hauled the Fjord Elk off the slipway, to rock gently beside Black Eagle. Now was the moment when the raiding began and, on the strength of it, Finn would go or stay; that sank my stomach to my boot tops.

It was a good ship, our Elk – fifteen benches each side and no Slav tree trunk, but a properly straked, oak-keeled drakkar that had survived portage and narrow rivers on at least two trips to Gardariki.

All the same, it was a bairn next to Black Eagle, which had thirty oars a side and was as long as fifteen tall men laid end to end. It was tricked out in gilding, painted red and black, with the great black eagle prow and a crew of growlers who knew they had the best and fastest ship afloat. They and the Oathsworn chaffered and jeered at each other, straining muscle and sinew to get the Elk into the water, then demanding a race up the fjord to decide which ship and crew was better.

Into the middle of this came the queen, ponderous as an Arab slave ship, with Thordis and Ingrid and Thorgunna round her and Jasna lumbering ahead. As this woman-fleet sailed past me, heading towards Jarl Brand, Thorgunna raised weary eyebrows.

The jarl had his back to Queen Sigrith as she came up and almost leapt out of his nice coloured tunic when she spoke. Then, flustered and annoyed at having been so taken by surprise, he scowled at her, which was a mistake.

Sigrith’s voice was shrill and high. Before, it might have been mistaken for girlish, but fear of childbirthing had sucked the sweetness out of it and her Polan accent was thick, so her demands to know when they were sailing from this dreadful place to one which did not smell of fish and sweaty men, had a rancid bite.

If Jarl Brand had an answer, he never gave it; one of my lookout thralls came pounding up, spraying mud and words in equal measure; a faering was coming up the fjord.

Such boats were too small to be feared, but the arrival of it was interesting enough to divert everyone, for which Brand was grateful. Yet, when it came heeling in, sail barely reefed and obviously badly handled, I felt an anchor-stone settle in my gut.

There were arrow shafts visible, and willing men splashed out, waist deep, to catch the little craft and help the man in it take in sail, for he was clearly hurt. They towed it in; two men were in it and blood sloshed in the scuppers; one man was dead and the survivor gasping with pain and badly cut about.

‘Skulli,’ Brand said, grim as old rock, and the anchor-stone sank lower; Skulli was his steward and I looked at the man, head lolling and leaking life as the women lifted him away to be cared for.

Brand stopped them and let Skulli leak while he gasped out the saga of what had happened. It took only moments to tell – Styrbjorn had arrived, with at least five ships and the men for them, clearly bound for a slaughter against his uncle’s right-hand man, to make a show of what he was capable of if things did not go his way.

Jarl Brand’s hall was burning, his men dead, his thralls fled, his women taken.

The black dog of it crushed everyone for a moment, then shook itself; men bellowed and all was movement. I saw Finn’s face and the mad joy on it was clear as blood on snow.

While Thorgunna and Thordis hauled Skulli off and yelled out for Bjaelfi to bring his skill and healing runes, Brand took my arm and led me a little way aside while men rushed to make Black Eagle ready. His face was now as bone-coloured as his hair.

‘I have to go to King Eirik,’ he declared. ‘Add my ship to his and what men I can sweep up on the way. Styrbjorn, if he is stupid, will stay to fight us and we will kill him. If not, he will flee and I will chase him and make him pay for what he has done.’

‘I can have the Elk ready in an hour or two,’ I said, then stopped as he shook his head.

‘Serve me better,’ he answered. ‘Call up your Oathsworn to this place. Look after the queen. I can hardly take her with me.’

That stopped my mouth, sure as a hand over it. He returned my look with a cliff of a face and eyes that said there would be no arguing; yet he cracked the stone of him an instant later, when he shot a sideways glance to where Koll watched, round-eyed, as men bustled. I did not need him to say more.

‘The queen and son both, then,’ I replied, feeling the sick dread of what would happen if Styrbjorn sent ships here, for it would take time to send out word to the world that Hestreng needed the old Oathsworn back. Jarl Brand saw it, too, and nodded briefly.

‘I will leave thirty of my crew – I wish it were more.’

It was generous, for the ones he had left would break themselves to run Black Eagle home, with no relief. It was also a marker of what he feared and I forced a smile.

‘Who will attack the Oathsworn?’ I countered, but there was no mirth in the twist of a grin he gave, turning away to bawl orders to his men.

There was a great milling of movement and words; I sent Botolf stumping off to bring the thirty of Jarl Brand’s crew. They stood forlorn and grim on the shore as their oarmates sailed away – but there was none more cliff-faced and black-scowling than Finn, watching others sail away to the war he wanted. Then I gathered up Botolf’s daughter, little red-haired Helga, and made her laugh, as much to make me feel better as her. Ingrid smiled.

Jasna waddled up to me, the queen moving ponderously behind her, made bulkier still by furs against the chill.

‘Her Highness wishes to know what blot you will make for the jarl’s journey,’ she demanded and her tone made me angry, since she was a thrall when all was said and done. I tossed Helga in the air and made her scream.

‘Laughter,’ I answered brusquely. ‘The gods need it sometimes.’

Jasna blinked at that, then went back to the queen, walking like a loaded pack pony; there were whispers back and forth. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Thorgunna scowling at me and in answer I carried on playing with the child.

‘This is not seemly,’ said an all-too familiar voice, jerking me from Helga’s gurgles. The queen stood in front of me, mittened hands folded over her swollen belly, frowning.

‘Seemly?’

She waved a small hand, like a little furred paw in the mitten. Her face was sharp as a cat’s and would have been pretty save for the lines at the edges of her mouth.

‘You are godi here. This is not…It has no…dignitas.’

‘You sound like a Christ follower,’ I answered shortly, putting Helga down; she trundled off towards her mother, who gathered her up. I saw Thorgunna closing on us, fast as a racing drakkar.

‘Christ follower!’

It was an explosion of shriek and I turned my head from it, as you would from an icy blast. Then I shrugged, for this queen, her young and beautiful face twisted with outrage, annoyed me more and more. I was annoyed, too, to have forgotten that the Christ godlet had been foisted on her father and his people; like the rest of them, she resented this.

‘They also confuse misery and prayer,’ I managed to answer and heard a chuckle I recognised as Leo. Thorgunna bustled up, managing to elbow me in the ribs.

‘Highness,’ she said to Sigrith, with a sweet smile. ‘I have everything prepared – what do men know of sacrifice?’

Mollified, the queen allowed herself to be led away, followed by Jasna, who threw me a venomous glare. The ever-present, ever-silent Mazur girl followed after, but paused to shoot me a quick glance from those dark eyes; afterwards, I realised what had made me remember it. It was the first time she had looked directly at anyone at all.

At the time, I heard a little laugh which distracted me from thoughts of the girl and turned my head to where Leo watched, swathed in a cloak, hands shoved deep inside its folds.

‘I thought traders of your standing had more diplomacy,’ he offered and I said nothing, knowing he had the right of it and that my behaviour had been, at best, childish.

‘But she galls, does she not?’ he added, as if reading my mind.

‘Even less soil there than here for your Christ seed,’ I countered. ‘Even if you get to the court. Your visit to Uppsalla is proving a failure.’

He smiled the moon-faced smile of a man who did not think anything he did was a failure, then inclined his head and moved off, leaving me with the last view of Black Eagle, raising sail and speeding off into the grey distance.

I felt rain spot my neck and shivered, looked up to a pewter sky and offered a prayer to bluff Thor and Aegir of the waves and Niord, god of the coasts, for a good blow and some tossing white-caps. A storm sea would keep us safe…

I rose in the night and left my sleeping area, mumbling to a dreamy Thorgunna about the need for a privy, which was a lie. I stepped through the hall of grunting and snores and soft stirrings in the dark, past the pitfire’s grey ash, where little red eyes watched me step out of the hall.

The sharp air made me wish I had brought a cloak, made me wonder at this foolishness. There was rain in that air, yet no storm and the fear of that lack filled me. Dreams I knew – Odin’s arse, I had been hag-ridden by dreams all my life – but this was strange, a formless half-life, a draugr of a feeling that ruined sleep and nipped my waking heels.

Never before or since have I felt the power of the prow beast on a raiding ship as it locks jaws with the spirit of the land – but I felt them both that night, muscled and snarling shadows in the dark. Even then, I knew Randr Sterki was coming.

Yet the world remained the same, etched in black and silver, misted in shreds even in the black night. A dog fox barked far out on the pasture; the great dark of Ginnungagap still held the embers of Muspelheim, flung there by Odin’s brothers, Vili and Ve. Between scudding clouds, I found Aurvandill’s Toe and the Eyes of Thjazi after a search, but easily found the Wagon Star, which guides prow beasts everywhere. The one on Randr’s ship would be following it like a spooring wolf.

There was a closer light from the little building that housed Ref’s forge, a soft glow and I moved to it, drawn by the hope of heat. A few steps from it, the voices halted me – I have no idea why, since they were ones I knew; Ref was there and Botolf with him and the thrall boy, Toki.

Ref was nailing, which was a simple thing but a steading needed lots of them and he clearly took comfort in the easy repetitive task; he took slim lengths of worked bog-iron, flared one end and pointed the other, two taps for one, four for the other, then a plunge into the quench and a drop into a box. Even for that simple task, he kept the light in the forge dim, so that he could read the colour of the fire and the heated iron.

Toki, a doll-like silhouette with his back to me, worked the bellows and hugged his reedy arms between times, chilled despite the flames in his one-piece kjartan and bare feet, his near-bald head shining in the red light.

The place had the burned-hair smell of charred hooves, braided with the tang of sea-salt, charcoal and horse piss. In the dim light of the forge-fire and a small horn lantern above Botolf’s head, Ref looked like a dwarf and Botolf a giant, the one forging some magical thing, the other red-dyed with light and speaking in a low rumble, like boulders grinding.

‘That dog fox is out again,’ he was saying. ‘He’s after the chickens.’

‘That’s why we coop them,’ Ref replied, concentrating. Tap, tap. Pause. Tap, tap, tap, tap. Plunge and hiss. He picked up another length.

‘He won’t come near. He is afraid of the hounds,’ Botolf replied, shifting his weight. He nudged Toki, who pumped the bellows a few times.

‘Why is he afraid?’ the boy asked. ‘He can run.’

‘Because the hounds run slower but longer and will kill him,’ answered Ref. ‘So would you be afraid.’

The boy shivered. ‘I am afraid even in my dreams,’ he answered and Botolf looked at him.

‘Dreams, little Toki? What dreams? My Helga has dreams, too, which make her afraid. What do you dream?’

The boy shrugged. ‘Falling from a high place, like Aoife says my da did.’

Botolf nodded soberly, remembering that Toki had been fathered by a thrall called Geitleggr, whose hairy goat legs had given him the only name he had known – but none of the animal’s skill when it came to gathering eggs on narrow ledges. His mother, too, had died, of too much work, too little food and winter and now Aoife looked out for Toki, as much as anyone did.

‘I like high places,’ Botolf said, seeking to reassure the boy. ‘They are in nearly all my dreams.’

Ref absently pinched out a flaring ember on his already scorch-marked old tunic and I doubted if his horn-skinned fingers felt it. He never took his eyes from the iron, watching the colour of the flames for the right moment, even on just a nail.

Tap, tap, tap, tap – plunge, hiss.

‘What are they, then, these dreams of yours, Botolf?’ Ref wanted to know, sliding another length of bog-iron into the coals and jerking his chin at Toki to start pumping.

Botolf tapped his timber foot on the side of the oak stump which held the spiked anvil.

‘Since I got this, wings,’ he answered. ‘I dream I have wings. Big black ones, like a raven.’

‘What does it feel like?’ Toki asked, peering curiously. ‘Is it like a real leg?’

‘Mostly,’ answered Botolf, ‘except when it itches, for you cannot scratch it.’

‘Does it itch, then?’ Ref asked, pausing in wonder. ‘Like a real leg?’

Botolf nodded.

‘Did some magic woodworker make it so that it itched?’ Toki wanted to know and Botolf chuckled.

‘If he did, I wish he would come back and unmake it – or at least let me scratch. I dream of that when I am not dreaming of wings.’

‘Does no-one dream of proper things any more?’ Ref grumbled, turning the bog-iron length in the coals. ‘Wealth and fame and women?’

‘I have all three,’ Botolf answered. ‘I have no need of that dream.’

‘I dream of food most often,’ Toki admitted and the other two laughed; boys seldom had enough to eat and thralls never did.

‘Sing a song,’ Ref said, ‘soft now, so as not to wake everyone. Pick a good one and it will go into the iron and make the nails stronger.’

So Toki sang, a child song, a soft song of the sea and being lost on it. The wave of it left me stranded at the edge of darkness, icy and empty and wondering why he had chosen that of all songs and if the hand of Odin was in it.

I had heard that song before, in another place. We had come ashore in the night, blacker than the night itself with hate and fear, unseen, unheard until we raved down on Klerkon’s steading on Svartey at dawn – a steading like this, I remembered, sick and cold. Only one fighting man had been there and he had been easily killed by Kvasir and Finn.

Things had been done, as they always were in such events, made more savage because it was Klerkon we hunted and he had stolen Thorgunna’s sister, Thordis. He was not there, but all his folk’s women and bairns were and, prowling for him, I had heard the singing, sweet in the dawn’s dim, a song to keep out the fear.

I heard it stop, too. I had come upon the great tangle-haired growler who had cut it out of the girl’s throat with a single slash, his blade clotted with sticky darkness and strands of hair. He had turned to me, all beard and mad grin and I had known him at once – Red Njal, limping Red Njal, who now played with Botolf’s Helga and carved dolls for her.

Beyond, all twisted limbs and bewildered faces, were the singer’s three little siblings: blood smoked in the hearthfire coals and puddled the stones. The thrall-nurse was there, too, forearm hacked through where she had flung up her arms in a last desperate, useless attempt to ward off an axe edge. Red Njal was on his knees in the blood, rifling for plunder.