Полная версия

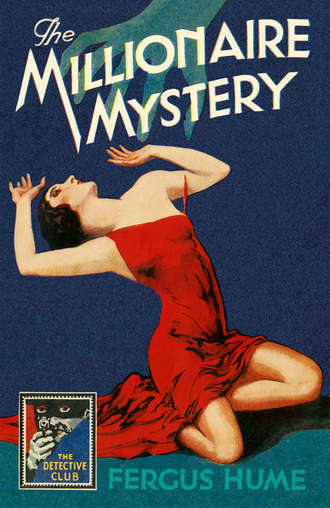

The Millionaire Mystery

She looked up wistfully to the blue sky.

‘At all events, he is at peace now,’ she said, her lip quivering. ‘I know he was often very unhappy, poor father! He used to sit for hours frowning and perplexed, as if there was something terrible on his mind.’

Alan’s face was turned away now, and his brow was wrinkled. He seemed absorbed in thought, as though striving to elucidate some problem suggested by her words.

Wrapped up in her own sorrow, the girl did not notice his momentary preoccupation, but continued:

‘He never said good-bye to me. Dr Warrender said he was insensible for so long before death that it was useless my seeing him. He kept me out of the room, so I only saw him—afterwards. I’ll never forgive the doctor for it. It was cruel!’

She sobbed hysterically.

‘Sophy,’ said Alan suddenly, ‘had your father any enemies?’

She looked round at him in astonishment.

‘I don’t know. I don’t think so. Why should he? He was the kindest man in the world.’

‘I am sure he was,’ replied the young man warmly; ‘but even the kindest may have enemies.’

‘He might have made enemies in Africa,’ she said gravely. ‘It was there he made his money, and I suppose there are people mean enough to hate a man who is successful, especially if his success results in a fortune of some two millions. Father used to say he despised most people. That was why he lived so quietly at the Moat House.’

‘It was particularly quiet till you came, Sophy.’

‘I’m sure it was,’ she replied, with the glimmer of a smile. ‘Still, although he had not me, you had your profession.’

‘Ah! my poor profession! I always regret having given it up.’

‘Why did you?’

‘You know, Sophy. I have told you a dozen times. I wanted to be a surgeon, but my father always objected to a Thorold being of service to his fellow-creatures. I could never understand why. The estate was not entailed, and by my father’s will I was to lose it, or give up all hope of becoming a doctor. For my mother’s sake I surrendered. But I would choose to be a struggling surgeon in London any day, if it were not for you, Sophy dear.’

‘Horrid!’ ejaculated Miss Marlow, elevating her nose. ‘How can you enjoy cutting up people? But don’t let us talk of these things; they remind me of poor dear father.’

‘My dear, you really should not be so morbid. Death is only natural. It is not as though you had been with him all your life, instead of merely three years.’

‘I know; but I loved him none the less for that. I often wonder why he was away so long.’

‘He was making his fortune. He could not have taken you into the rough life he was leading in Africa. You were quite happy in your convent.’

‘Quite,’ she agreed, with conviction. ‘I was sorry to leave it. The dear sisters were like mothers to me. I never knew my own mother. She died in Jamaica, father said, when I was only ten years old. He could not bear to remain in the West Indies after she died, so he brought me to England. While I was in the convent I saw him only now and again until I had finished my education. Then he took the Moat House—that was five years ago, and two years after that I came to live with him. That is all our history, Alan. But Joe Brill might know if he had any enemies.’

‘Yes, he might. He lived thirty years with your father, didn’t he? But he can keep his own counsel—no one better.’

‘You are good at it too, Alan. Where were you last night? You did not come to see me.’

He moved uneasily. He had his own reasons for not wishing to give a direct answer.

‘I went for a long walk—to—to—to think out one or two things. When I got back it was too late to see you.’

‘What troubled you, Alan? You have looked very worried lately. I am sure you are in some trouble. Tell me, dear; I must share all your troubles.’

‘My dearest, I am in no trouble’—he kissed her hand—‘but I am your trustee, you know and it is no sinecure to have the management of two millions.’

‘It’s too much money,’ she said. ‘Let us dispose of some of it, then you need not be worried. Can I do what I like with it?’

‘Most of it—there are certain legacies. I will tell you about them later.’

‘I am afraid the estate will be troublesome to us, Alan. It’s strange we should have so much money when we don’t care about it. Now, there is Dr Warrender, working his life out for that silly extravagant wife of his!’

‘He is very much in love with her, nevertheless.’

‘I suppose that’s why he works so hard. But she’s a horrid woman, and cares not a snap of her fingers for him—not to speak of love! Love! why, she doesn’t know the meaning of the word. We do!’ And, bending over, Sophy kissed him.

Then promptly there came from Miss Parsh the reminder that it was time for tea.

‘Very well, Vicky, I dare say Alan would like you to give him a cup,’ replied Sophy.

‘Frivolous as ever, Sophia! I give up a hope of forming your character—now!’

‘Alan is doing that,’ replied the girl.

In spite of her sorrow, Sophy became fairly cheerful on the way back to the hotel. Not so Alan. He was silent and thoughtful, and evidently meditating about the responsibilities of the Marlow estate. As they walked along the parade with their chaperon close behind, they came upon a crowd surrounding a fat man dressed in dingy black. He was reciting a poem, and his voice boomed out like a great organ. As they passed, Alan noticed that he darted a swift glance at them, and eyed Miss Marlow in a particularly curious manner. The recitation was just finished, and the hat was being sent round. Sophy, always kind-hearted, dropped in a shilling. The man chuckled.

‘Thank you, lady,’ said he; ‘the first of many, I hope.’

Alan frowned, and drew his fiancée away. He took little heed of the remark at the time; but it occurred to him later when circumstances had arisen which laid more stress on its meaning.

Miss Vicky presided over the tea—a gentle feminine employment in which she excelled. She did most of the talking; for Sophy was silent, and Alan inclined to monosyllables. The good lady announced that she was anxious to return to Heathton.

‘The house weighs on my mind,’ said she, lifting her cup with the little finger curved. ‘The servants are not to be trusted. I fear Mrs Crammer is addicted to ardent spirits. Thomas and Jane pay too much attention to one another. I feel a conviction that, during my absence, the bonds of authority will have loosened.’

‘Joe,’ said Alan, setting down his cup; ‘Joe is a great disciplinarian.’

‘On board a ship, no doubt,’ assented Miss Vicky; ‘but a rough sailor cannot possibly know how to control a household. Joseph is a fine, manly fellow, but boisterous—very boisterous. It needs my eye to make domestic matters go smoothly. When will you be ready to return, Sophy, my dear?’

‘In a week—but Alan has suggested that we should go abroad.’

‘What! and leave the servants to wilful waste and extravagance? My love!’—Miss Vicky raised her two mittened hands—‘think of the bills!’

‘There is plenty of money, Vicky.’

‘No need there should be plenty of waste. No; if we go abroad, we must either shut up the house or let it.’

‘To the Quiet Gentleman?’ said Sophy, with a laugh.

Alan looked up suddenly.

‘No, not to him. He is a mysterious person,’ said Miss Vicky. ‘I do not like such people, though I dare say it is only village gossip which credits him with a strange story.’

‘Just so,’ put in Alan. ‘Don’t trouble about him.’

Miss Vicky was still discussing the possibility of a trip abroad, when the waiter entered with a note for Sophy.

‘It was delivered three hours ago,’ said the man apologetically, ‘and I quite forgot to bring it up. So many visitors, miss,’ he added, with a sickly smile.

Sophy took the letter. The envelope was a thick creamy one, and the writing of the address elegant in the extreme.

‘Who delivered it?’ she asked.

‘A fat man, miss, with a red face, and dressed in black.’

Alan’s expression grew somewhat anxious.

‘Surely that describes the man we saw reciting?’

‘So it does.’ Sophy eyed the letter dubiously. ‘Had he a loud voice, Simmonds?’

‘As big as a bell, miss, and he spoke beautiful: but he wasn’t gentry, for all that,’ finished Simmonds with conviction.

‘You can go,’ said Alan. Then he turned to Sophy, who was opening the envelope. ‘Let me read that letter first,’ he said.

‘Why, Alan? There is no need. It is only a begging letter. Come and read it with me.’

He gave way, and looked over her shoulder at the elaborate writing.

‘Miss’ (it began),

‘The undersigned, if handsomely remunerated, can give valuable information regarding the removal of the body of the late Richard Marlow from its dwelling in Heathton Churchyard. Verbum dat sapienti! Forward £100 to the undersigned at Dixon’s Rents, Lambeth, and the information will be forthcoming. If the minions of the law are invoked the undersigned with vanish, and his information lost.

‘Faithfully yours, Miss Sophia Marlow,

‘CICERO GRAMP.’

As she comprehended the meaning of this extraordinary letter, Sophy became paler and paler. The intelligence that her father’s body had been stolen was too much for her, and she fainted.

Thorold called loudly to Miss Vicky.

‘Look after her,’ he said, stuffing the letter into his pocket. ‘I shall be back soon.’

‘But what—what—?’ began Miss Vicky.

She spoke to thin air. Alan was running at top speed along the parade in search of the fat man.

But all search was vain. Cicero, the astute, had vanished.

CHAPTER IV

ANOTHER SURPRISE

HEATHTON was only an hour’s run by rail from Bournemouth, so that it was easy enough to get back on the same evening. On his return from his futile search for Cicero, Alan determined to go at once to the Moat House. He found Sophy recovered from her faint, and on hearing of his decision, she insisted upon accompanying him. She had told Miss Vicky the contents of the mysterious letter, and that lady agreed that they should leave as soon as their boxes could be packed.

‘Don’t talk to me, Alan!’ cried Sophy, when her lover objected to this sudden move. ‘It would drive me mad to stay here doing nothing, with that on my mind.’

‘But, my dear girl, it may not be true.’

‘If it is not, why should that man have written? Did you see him?’

‘No. He has left the parade, and no one seems to know anything about him. It is quite likely that when he saw us returning to the hotel he cleared out. By this time I dare say he is on his way to London.’

‘Did you see the police?’ she asked anxiously.

‘No,’ said Alan, taking out the letter which had caused all this trouble; ‘it would not be wise. Remember what he says here: If the police are called in he will vanish, and we shall lose the information he seems willing to supply.’

‘I don’t think that, Mr Thorold,’ said Miss Vicky. ‘This man evidently wants money, and is willing to tell the truth for the matter of a hundred pounds.’

‘On account,’ remarked Thorold grimly; ‘as plain a case of blackmail as I ever heard of. Well, I suppose it is best to wait until we can communicate with this—what does he call himself?—Cicero Gramp, at Dixon’s Rents, Lambeth. He can be arrested there, if necessary. What I want to do now is to find out if his story is true. To do this I must go at once to Heathton, see the Rector, and get the coffin opened.’

‘I will come,’ insisted Sophy. ‘Oh, it is terrible to think that poor father was not allowed to rest quietly even in his grave.’

‘Of course, it may not be true,’ urged Alan again. ‘I don’t see how this tramp could have got to know of it.’

‘Perhaps he helped to violate the secrets of the tomb?’ suggested Miss Vicky.

‘In that case he would hardly put himself within reach of the law,’ Alan said, after a pause. ‘Besides, if the vault had been broken into we should have heard of it from Joe.’

‘Why should it be broken into, Alan? The key—’

‘I have one key, and the Rector has the other. My key is in my desk at the Abbey Farm, and no doubt Phelps has his safe enough.’

‘Your key may have been stolen.’

‘It might have been,’ admitted Alan. ‘That is one reason why I am so anxious to get back tonight. We must find out also if the coffin is empty.’

‘Yes, yes; let us go at once!’ Sophy cried feverishly. ‘I shall never rest until I learn the truth. Come, Vicky, let us pack. When can we leave, Alan?’

Thorold glanced at his watch.

‘In half an hour,’ he said. ‘We can catch the half-past six train. Can you be ready?’

‘Yes, yes!’ cried she, and rushed out of the room.

Miss Vicky was about to follow, but Alan detained her.

‘Give her a sedative or something,’ he said, ‘or she will be ill.’

‘I will at once. Have a carriage at the door in a quarter of an hour, Mr Thorold. We can be ready by then. I suppose it is best she should go?’

‘Much better than to leave her here. We must set her mind at rest. At this rate she will work herself into a fever.’

‘But if this story should really be true?’

‘I don’t believe it for a moment,’ replied Alan. But he was evidently uneasy, and could not disguise the feeling. ‘Wait till we get to Heathton—wait,’ and he hastily left the room.

Miss Vicky was surprised at his agitation, for hitherto she had credited Alan with a will strong enough to conceal his emotions. The old lady hurried away to the packing, and shook her head as she went.

Shortly they were settled in a first-class carriage on the way to Heathton. Sophy was suffering acutely, but did all in her power to hide her feelings, and, contrary to Alan’s expectations, hardly a word was spoken about the strange letter, and the greater part of the journey was passed in silence. At Heathton he put Sophy and Miss Vicky into a fly.

‘Drive at once to the Moat House,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow we shall consider what is to be done.’

‘And you, Alan?’

‘I am going to see Mr Phelps. He, if anyone, will know what value to put upon that letter. Try and sleep, Sophy. I shall see you in the morning.’

‘Sleep?’ echoed the poor girl, in a tone of anguish. ‘I feel as though I should never sleep again!’

When they had driven away, Alan him took the nearest way to the Rectory. It was some way from the station, but Alan was a vigorous walker, and soon covered the distance. He arrived at the door with a beating heart and dry lips, feeling, he knew not why, that he was about to hear bad news. The grey-haired butler ushered him into his master’s presence, and immediately the young man felt that his fears were confirmed. Phelps looked worried.

He was a plump little man, neat in his dress and cheerful in manner. He was a bachelor, and somewhat of a cynic. Alan had known him all his life, and could have found no better adviser in the dilemma in which he now found himself. Phelps came forward with outstretched hands.

‘My dear boy, I am indeed glad! What good fairy sent you here? A glass of port? You look pale. I am delighted to see you. If you had not come I should have had to send for you.’

‘What do you wish to see me about, sir? asked Alan.

‘About the disappearance of these two people.’

‘What two people?’ asked the young man, suddenly alert. ‘You forget that I have been away from Heathton for the last three days.’

‘Of course, of course. Well, one is Brown, the stranger who stayed with Mrs Marry.’

‘The Quiet Gentleman?’

‘Yes. I heard them call him so in the village. A very doubtful character. He never came to church,’ said the Rector sadly. ‘However, it seems he has disappeared. Two nights ago—in fact, upon the evening of the day upon which poor Marlow’s funeral took place, he left his lodgings for a walk. Since then,’ added the Rector impressively, ‘he has not returned.’

‘In plain words, he has taken French leave,’ said Thorold, filling his glass.

‘Oh, I should not say that, Alan. He paid his weekly account the day before he vanished. He left his baggage behind him. No, I don’t think he intended to run away. Mrs Marry says he was a good lodger, although she knew very little about him. However, he has gone, and his box remains. No one saw him after he left the village about eight o’clock. He was last seen by Giles Hale passing the church in the direction of the moor. Today we searched the moor, but could find no trace of him. Most mysterious,’ finished the Rector, and took some port.

‘Who is the other man?’ asked Alan abruptly.

‘Ah! Now you must be prepared for a shock, Alan. Dr Warrender!’

Thorold bounded out of his seat.

‘Is he lost too?’

‘Strangely enough, he is,’ answered Phelps gravely. ‘On the night of the funeral he went out at nine o’clock in the evening to see a patient. He never came back.’

‘Who was the patient?’

‘That is the strangest part of it. Brown, the Quiet Gentleman, was the patient. Mrs Warrender, who, as you may guess, is quite distracted, says that her husband told her so. Mrs Marry declares that the doctor called after nine, and found Brown was absent.’

‘What happened then?’ demanded Alan, who had been listening eagerly to this tale.

‘Dr Warrender, according to Mrs Marry, asked in what direction her lodger had gone. She could not tell him, so, saying he would call again in an hour or so, he went. And, of course, he never returned.’

‘Did Brown send for him?’

‘Mrs Marry could not say. Certainly no message was sent through her.’

‘Was Brown ill?’

‘Not at all, according to his landlady. We have been searching for both Brown and Warrender, but have found no traces of either.’

‘Humph!’ said Thorold, after a pause. ‘I wonder if they met and went away together?’

‘My dear lad, where would they go to?’ objected the Rector.

‘I don’t know; I can’t say. The whole business is most mysterious.’ Alan stopped, and looked sharply at Mr Phelps. ‘Have you the key of the Marlow vault in your possession?’

‘Yes, of course, locked in my safe. Your question is most extraordinary.’

The other smiled grimly.

‘My explanation is more extraordinary still.’ He took out Mr Gramp’s letter and handed it to the Rector. ‘What do you think of that, sir?’

‘Most elegant calligraphy,’ said the good man. ‘Why, bless me!’ He read on hurriedly, and finally dropped the letter with a bewildered air. ‘Bless me, Alan!’ he stammered. ‘What—what—what—’

Thorold picked it up and smoothed it out on the table.

‘You see, this man says the body has been stolen. Do you know if the door of the vault has been broken open?’

‘No, no, certainly not!’ cried the Rector, rising fussily. ‘Come to my study, Alan; we must see if it is all right. It must be,’ he added emphatically. ‘The key of the safe is on my watch-chain. No one can open it. Oh dear! Bless me!’

He bustled out of the room, followed by Alan.

A search into the interior of the safe resulted in the production of the key.

‘You see,’ cried Phelps, waving it triumphantly, ‘it is safe. The door could not have been opened with this. Now your key.’

‘My key is in my desk at the Abbey Farm—locked up also,’ said the young man hastily. ‘I’ll see about it tonight. In the meantime, sir, bring that key with you, and we will go into the vault.’

‘What for?’ demanded the Rector sharply. ‘Why should we go there?’

‘Can’t you understand?’ said Alan impatiently. ‘I want to find out if this letter is true or false—if the body of Mr Marlow has been removed.’

‘But I—I—can’t!’ gasped the Rector. ‘I must apply to the Bishop for—’

‘Nonsense, sir! We are not going to exhume the body. It’s not like digging up a grave. All that is necessary is to look at the coffin resting in its niche. We can tell from the screws and general appearance if it has been tampered with.’

The clergyman sat down and wiped his bald head.

‘I don’t like it,’ he said. ‘I don’t like it at all. Still, I don’t suppose a look at the coffin can harm anyone. We’ll go, Alan, we’ll go; but I must take Jarks.’

‘The sexton?’

‘Yes. I want a witness—two witnesses; you are one, Jarks the other. It is a gruesome task that we have before us.’ He shuddered again. ‘I don’t like it. Profanation!’

‘If this letter is to be believed, the profanation has already been committed.’

‘Cicero Gramp,’ repeated Mr Phelps as they went out. ‘Who is he?’

‘A fat man—a tramp—a reciter. I saw him at Bournemouth. He delivered that letter at the hotel himself; the waiter described him, and as the creature is a perfect Falstaff, I recalled his face—I had seen him on the parade. I went at once to see if I could find him, but he was gone.’

‘A fat man,’ said the Rector. ‘Humph! He was at the Good Samaritan the other night. I’ll tell you about him later.’

The two trudged along in silence and knocked up Jarks, the sexton, on the way. They had no difficulty in rousing him. He came down at once with a lantern, and was much surprised to learn the errand of Rector and Squire.

‘Want to have a look at Muster Marlow’s vault,’ said he in creaking tones. ‘Well, it ain’t a bad night for a visit, I do say. But quiet comp’ny, Muster Phelps and Muster Thorold, very quiet. What do ye want to see Muster Marlow for?’

‘We want to see if his body is in the vault,’ said Alan.

‘Why, for sure it’s there, sir. Muster Marlow don’t go visiting.’

‘I had a letter at Bournemouth, Jarks, to say the body had been stolen.’

Jarks stared.

‘It ain’t true!’ he cried in a voice cracked with passion. ‘It’s casting mud on my ’arning my bread. I’ve bin sexton here fifty year, man and boy—I never had no corp as was stolen. They all lies comfortable arter my tucking them in. Only Gabriel’s trump will wake ’em.’

By this time they were round the Lady Chapel, and within sight of the tomb. Phelps, too much agitated to speak, beckoned to Jarks to hold up the lantern, which he did, grumbling and muttering the while.

‘I’ve buried hundreds of corps,’ he growled, ‘and not one of ’em’s goed away. What ’ud they go for? I make ’em comfortable, I do.’

‘Hold the light steady, Jarks,’ said the Rector, whose own hand was just as unsteady. He could hardly get the key into the lock.

At last the door was open, and headed by Jarks, with the lantern, they entered. The cold, earthy smell, the charnel-house feeling shook the nerves of both men. Jarks, accustomed as he was to the presence of the dead, hobbled along without showing any emotion other than wrath, and triumphantly swung the lantern towards a niche wherein reposed a coffin.

‘Ain’t he there quite comfortable?’ wheezed he. ‘Don’t I tell you they never goes from here? It’s a lovely vault; no corp ’ud need a finer.’

‘Wait a bit!’ said Alan, stepping forward. ‘Turn the light along the top of the coffin, Jarks. Hullo! the lid’s loose!’

‘An’ unscrewed!’ gasped the sexton. ‘He’s bin getting out.’

‘Unscrewed—loose!’ gasped the Rector in his turn. The poor man felt deadly sick. ‘There must be some mistake.’

‘No mistake,’ said Alan, slipping back the lid. ‘The body has been stolen.’

‘No ’t’ain’t!’ cried Jarks, showering the light on the interior of the coffin. ‘There he is, quiet an’—why,’ the old man broke off with a cry, ‘the corp ain’t in his winding-sheet!’

Phelps looked, Alan looked. The light shone on the face of the dead.

Phelps groaned.

‘Merciful God!’ he groaned, ‘it is Dr Warrender’s body!’

CHAPTER V

A NINE DAYS’ WONDER

THERE was sensation enough and to spare in Heathton next morning. Jarks lost no time in spreading the news. He spent the greater part of the day in the taproom of the Good Samaritan, accepting tankards of beer and relating details of the discovery. Mrs Timber kept him as long as she could; for Jarks, possessed of intelligence regarding the loss of Mr Marlow’s body, attracted customers. These, thirsty for news or drink, or both, flocked like sheep into the inn.