Полная версия

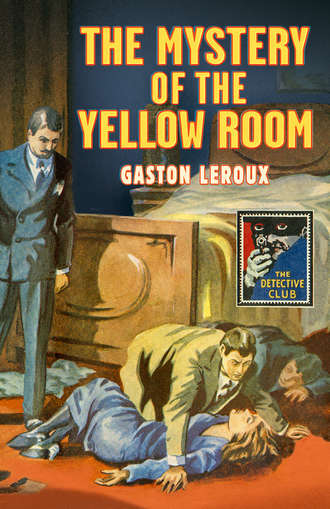

The Mystery of the Yellow Room

‘With the concierge I hurried back to the pavilion. The door, in spite of the furious attempts of Monsieur Stangerson and Bernier to burst it open, was still holding firm; but at length, it gave way before our united efforts—and then what a sight met our eyes! I should tell you that, behind us, the concierge held the laboratory lamp—a powerful lamp, that lit the whole chamber.

‘I must also tell you, monsieur, that the Yellow Room is a very small room. Mademoiselle had furnished it with a fairly large iron bedstead, a small table, a night-commode; a dressing-table, and two chairs. By the light of the big lamp we saw all at a glance. Mademoiselle, in her night-dress, was lying on the floor in the midst of the greatest disorder. Tables and chairs had been overthrown, showing that there had been a violent struggle. Mademoiselle had certainly been dragged from her bed. She was covered with blood and had terrible marks of finger-nails on her throat—the flesh of her neck having been almost torn by the nails. From a wound on the right temple a stream of blood had run down and made a little pool on the floor. When Monsieur Stangerson saw his daughter in that state, he threw himself on his knees beside her, uttering a cry of despair. He ascertained that she still breathed. As to us, we searched for the wretch who had tried to kill our mistress, and I swear to you, monsieur, that, if we had found him, it would have gone hard with him!

‘But how to explain that he was not there, that he had already escaped? It passes all imagination! Nobody under the bed, nobody behind the furniture! All that we discovered were traces, blood-stained marks of a man’s large hand on the walls and on the door; a big handkerchief red with blood, without any initials, an old cap, and many fresh footmarks of a man on the floor—footmarks of a man with large feet whose boot-soles had left a sort of sooty impression. How had this man got away? How had he vanished? Don’t forget, monsieur, that there is no chimney in the Yellow Room. He could not have escaped by the door, which is narrow, and on the threshold of which the concierge stood with the lamp, while her husband and I searched for him in every corner of the little room, where it is impossible for anyone to hide himself. The door, which had been forced open against the wall, could not conceal anything behind it, as we assured ourselves. By the window, still in every way secured, no flight had been possible. What then? I began to believe in the Devil.

‘But we discovered my revolver on the floor! Yes, my revolver! Oh! That brought me back to the reality! The Devil would not have needed to steal my revolver to kill Mademoiselle. The man who had been there had first gone up to my attic and taken my revolver from the drawer where I kept it. We then ascertained, by counting the cartridges, that the assassin had fired two shots. Ah! It was fortunate for me that Monsieur Stangerson was in the laboratory when the affair took place and had seen with his own eyes that I was there with him; for otherwise, with this business of my revolver, I don’t know where we should have been—I should now be under lock and bar. Justice wants no more to send a man to the scaffold!’

The editor of the Matin added to this interview the following lines:

We have, without interrupting him, allowed Daddy Jacques to recount to us roughly all he knows about the crime of the Yellow Room. We have reproduced it in his own words, only sparing the reader the continual lamentations with which he garnished his narrative. It is quite understood, Daddy Jacques, quite understood, that you are very fond of your masters; and you want them to know it, and never cease repeating it—especially since the discovery of your revolver. It is your right, and we see no harm in it. We should have liked to put some further questions to Daddy Jacques—Jacques-Louis Moustier—but the inquiry of the examining magistrate, which is being carried on at the château, makes it impossible for us to gain admission at the Glandier; and, as to the oak wood, it is guarded by a wide circle of policemen, who are jealously watching all traces that can lead to the pavilion, and that may perhaps lead to the discovery of the assassin.

We have also wished to question the concierges, but they are invisible. Finally, we have waited in a roadside inn, not far from the gate of the château, for the departure of Monsieur de Marquet, the magistrate of Corbeil. At half-past five we saw him and his clerk and, before he was able to enter his carriage, had an opportunity to ask him the following question:

‘Can you, Monsieur de Marquet, give us any information as to this affair, without inconvenience to the course of your inquiry?’

‘It is impossible for us to do it,’ replied Monsieur de Marquet. ‘I can only say that it is the strangest affair I have ever known. The more we think we know something, the further we are from knowing anything!’

We asked Monsieur de Marquet to be good enough to explain his last words; and this is what he said—the importance of which no one will fail to recognize:

‘If nothing is added to the material facts so far established, I fear that the mystery which surrounds the abominable crime of which Mademoiselle Stangerson has been the victim will never be brought to light; but it is to be hoped, for the sake of our human reason, that the examination of the walls, and of the ceiling of the Yellow Room—an examination which I shall tomorrow intrust to the builder who constructed the pavilion four years ago—will afford us the proof that may not discourage us. For the problem is this: we know by what way the assassin gained admission—he entered by the door and hid himself under the bed, awaiting Mademoiselle Stangerson. But how did he leave? How did he escape? If no trap, no secret door, no hiding place, no opening of any sort is found; if the examination of the walls—even to the demolition of the pavilion—does not reveal any passage practicable—not only for a human being, but for any being whatsoever—if the ceiling shows no crack, if the floor hides no underground passage, one must really believe in the Devil, as Daddy Jacques says!’

And the anonymous writer in the Matin added in this article—which I have selected as the most interesting of all those that were published on the subject of this affair—that the examining magistrate appeared to place a peculiar significance to the last sentence: ‘One must really believe in the Devil, as Jacques says.’

The article concluded with these lines:

We wanted to know what Daddy Jacques meant by the cry of the Bête du bon Dieu. The landlord of the Donjon Inn explained to us that it is the particularly sinister cry which is uttered sometimes at night by the cat of an old woman—Mother Angenoux, as she is called in the country. Mother Angenoux is a sort of saint, who lives in a hut in the heart of the forest, not far from the grotto of Sainte-Geneviève.

The Yellow Room, the Bête du bon Dieu, Mother Angenoux, the Devil, Sainte-Geneviève, Daddy Jacques—here is a well entangled crime which the stroke of a pickaxe in the wall may disentangle for us tomorrow. Let us at least hope that, for the sake of our human reason, as the examining magistrate says. Meanwhile, it is expected that Mademoiselle Stangerson—who has not ceased to be delirious and only pronounces one word distinctly, ‘Murderer! Murderer!’—will not live through the night.’

In conclusion, and at a late hour, the same journal announced that the Chief of the Sûreté had telegraphed to the famous detective, Frédéric Larsan, who had been sent to London for an affair of stolen securities, to return immediately to Paris.

CHAPTER II

IN WHICH JOSEPH ROULETABILLE APPEARS FOR THE FIRST TIME

I REMEMBER as well as if it had occurred yesterday, the entry of young Rouletabille into my bedroom that morning. It was about eight o’clock and I was still in bed reading the article in the Matin relative to the Glandier crime.

But, before going further, it is time that I present my friend to the reader.

I first knew Joseph Rouletabille when he was a young reporter. At that time I was a beginner at the Bar and often met him in the corridors of examining magistrates, when I had gone to get a ‘permit to communicate’ for the prison of Mazas, or for Saint-Lazare. He had, as they say, ‘a good nut’. He seemed to have taken his head—round as a bullet—out of a box of marbles, and it is from that, I think, that his comrades of the press—all determined billiard-players—had given him that nickname, which was to stick to him and be made illustrious by him. He was always as red as a tomato, now gay as a lark, now grave as a judge. How, while still so young—he was only sixteen and a half years old when I saw him for the first time—had he already won his way on the press? That was what everybody who came into contact with him might have asked, if they had not known his history. At the time of the affair of the woman cut in pieces in the Rue Oberskampf—another forgotten story—he had taken to one of the editors of the Epoque—a paper then rivalling the Matin for information—the left foot, which was missing from the basket in which the gruesome remains were discovered. For this left foot the police had been vainly searching for a week, and young Rouletabille had found it in a drain where nobody had thought of looking for it. To do that he had dressed himself as an extra sewer-man, one of a number engaged by the administration of the city of Paris, owing to an overflow of the Seine.

When the editor-in-chief was in possession of the precious foot and informed as to the train of intelligent deductions the boy had been led to make, he was divided between the admiration he felt for such detective cunning in a brain of a lad of sixteen years, and delight at being able to exhibit, in the ‘morgue window’ of his paper, the left foot of the Rue Oberskampf.

‘This foot,’ he cried, ‘will make a great headline.’

Then, when he had confided the gruesome packet to the medical lawyer attached to the journal, he asked the lad, who was shortly to become famous as Rouletabille, what he would expect to earn as a general reporter on the Epoque?

‘Two hundred francs a month,’ the youngster replied modestly, hardly able to breathe from surprise at the proposal.

‘You shall have two hundred and fifty,’ said the editor-in-chief; ‘only you must tell everybody that you have been engaged on the paper for a month. Let it be quite understood that it was not you but the Epoque that discovered the left foot of the Rue Oberskampf. Here, my young friend, the man is nothing, the paper everything.’

Having said this, he begged the new reporter to retire, but before the youth had reached the door he called him back to ask his name. The other replied:

‘Joseph Josephine.’

‘That’s not a name,’ said the editor-in-chief, ‘but since you will not be required to sign what you write it is of no consequence.’

The boy-faced reporter speedily made himself many friends, for he was serviceable and gifted with a good humour that enchanted the most severe-tempered and disarmed the most zealous of his companions. At the Bar café, where the reporters assembled before going to any of the courts, or to the Prefecture, in search of their news of crime, he began to win a reputation as an unraveller of intricate and obscure affairs which found its way to the office of the Chief of the Sûreté. When a case was worth the trouble and Rouletabille—he had already been given his nickname—had been started on the scent by his editor-in-chief, he often got the better of the most famous detective.

It was at the Bar café that I became intimately acquainted with him. Criminal lawyers and journalists are not enemies, the former need advertisement, the latter information. We chatted together, and I soon warmed towards him. His intelligence was so keen, and so original! And he had a quality of thought such as I have never found in any other person.

Some time after this I was put in charge of the law news of the Cri du Boulevard. My entry into journalism could not but strengthen the ties which united me to Rouletabille. After a while, my new friend being allowed to carry out an idea of a judicial correspondence column, which he was allowed to sign ‘Business’, in the Epoque, I was often able to furnish him with the legal information of which he stood in need.

Nearly two years passed in this way, and the better I knew him, the more I learned to love him; for, in spite of his careless extravagance, I had discovered in him what was, considering his age, an extraordinary seriousness of mind. Accustomed as I was to seeing him gay and, indeed, often too gay, I would many times find him plunged in the deepest melancholy. I tried then to question him as to the cause of this change of humour, but each time he laughed and made me no answer. One day, having questioned him about his parents, of whom he never spoke, he left me, pretending not to have heard what I said.

While things were in this state between us, the famous case of the Yellow Room took place. It was this case which was to rank him as the leading newspaper reporter, and to obtain for him the reputation of being the greatest detective in the world. It should not surprise us to find in the one man the perfection of two such lines of activity if we remember that the daily press was already beginning to transform itself and to become what it is today—the gazette of crime.

Morose-minded people may complain of this; for myself I regard it a matter for congratulation. We can never have too many arms, public or private, against the criminal. To this some people may answer that, by continually publishing the details of crimes, the press ends by encouraging their commission. But then, with some people we can never do right. Rouletabille, as I have said, entered my room that morning of the 26th of October, 1892. He was looking redder than usual, and his eyes were bulging out of his head, as the phrase is, and altogether he appeared to be in a state of extreme excitement. He waved the Matin with a trembling hand, and cried:

‘Well, my dear Sainclair—have you read it?’

‘The Glandier crime?’

‘Yes; the Yellow Room! What do you think of it?’

‘I think that it must have been the Devil or the Bête du bon Dieu that committed the crime.’

‘Be serious!’

‘Well, I don’t much believe in murderers who make their escape through walls of solid brick. I think Daddy Jacques did wrong to leave behind him the weapon with which the crime was committed and, as he occupied the attic immediately above Mademoiselle Stangerson’s room, the builder’s job ordered by the examining magistrate will give us the key of the enigma and it will not be long before we learn by what natural trap, or by what secret door, the old fellow was able to slip in and out, and return immediately to the laboratory to Monsieur Stangerson, without his absence being noticed. That, of course, is only an hypothesis.’

Rouletabille sat down in an armchair, lit his pipe, which he was never without, smoked for a few minutes in silence—no doubt to calm the excitement which, visibly, dominated him—and then replied:

‘Young man,’ he said, in a tone the sad irony of which I will not attempt to render, ‘young man, you are a lawyer and I doubt not your ability to save the guilty from conviction; but if you were a magistrate on the bench, how easy it would be for you to condemn innocent persons! You are really gifted, young man!’

He continued to smoke energetically, and then went on:

‘No trap will be found, and the mystery of the Yellow Room will become more and more mysterious. That’s why it interests me. The examining magistrate is right; nothing stranger than this crime has ever been known.’

‘Have you any idea of the way by which the murderer escaped?’ I asked.

‘None,’ replied Rouletabille, ‘none, for the present. But I have an idea as to the revolver; the murderer did not use it.’

‘Good Heavens! By whom, then, was it used?’

‘Why—by Mademoiselle Stangerson.’

‘I don’t understand—or rather, I have never understood,’ I said.

Rouletabille shrugged his shoulders.

‘Is there nothing in this article in the Matin by which you were particularly struck?’

‘Nothing—I have found the whole of the story it tells equally strange.’

‘Well, but—the locked door—with the key on the inside?’

‘That’s the only perfectly natural thing in the whole article.’

‘Really! And the bolt?’

‘The bolt?’

‘Yes, the bolt—also inside the room—a still further protection against entry? Mademoiselle Stangerson took quite extraordinary precautions! It is clear to me that she feared someone. That was why she took such precautions—even Daddy Jacques’s revolver—without telling him of it. No doubt she didn’t wish to alarm anybody, and least of all, her father. What she dreaded took place, and she defended herself. There was a struggle, and she used the revolver skilfully enough to wound the assassin in the hand—which explains the impression on the wall and on the door of the large, blood-stained hand of the man who was searching for a means of exit from the chamber. But she didn’t fire soon enough to avoid the terrible blow on the right temple.’

‘Then the wound on the temple was not done with the revolver?’

‘The paper doesn’t say it was, and I don’t think it was; because logically it appears to me that the revolver was used by Mademoiselle Stangerson against the assassin. Now, what weapon did the murderer use? The blow on the temple seems to show that the murderer wished to stun Mademoiselle Stangerson—after he had unsuccessfully tried to strangle her. He must have known that the attic was inhabited by Daddy Jacques, and that was one of the reasons, I think, why he must have used a quiet weapon—a life-preserver, or a hammer.’

‘All that doesn’t explain how the murderer got out of the Yellow Room,’ I observed.

‘Evidently,’ replied Rouletabille, rising, ‘and that is what has to be explained. I am going to the Château du Glandier, and have come to see whether you will go with me.’

‘I?’

‘Yes, my boy. I want you. The Epoque has definitely entrusted this case to me, and I must clear it up as quickly as possible.’

‘But in what way can I be of any use to you?’

‘Monsieur Robert Darzac is at the Château du Glandier.’

‘That’s true. His despair must be boundless.’

‘I must have a talk with him.’

Rouletabille said it in a tone that surprised me.

‘Is it because—you think there is something to be got out of him?’ I asked.

‘Yes.’

That was all he would say. He retired to my sitting-room, begging me to dress quickly.

I knew Monsieur Robert Darzac from having been of great service to him in a civil action, while I was acting as secretary to Maître Barbet Delatour. Monsieur Robert Darzac, who was at that time about forty years of age, was a professor of physics at the Sorbonne. He was intimately acquainted with the Stangersons, and, after an assiduous seven years’ courtship of the daughter, had been on the point of marrying her. In spite of the fact that she has become, as the phrase goes, ‘a person of a certain age,’ she was still remarkably good-looking. While I was dressing I called out to Rouletabille, who was impatiently moving about my sitting-room:

‘Have you any idea as to the murderer’s station in life?’

‘Yes,’ he replied; ‘I think if he isn’t a man in society, he is, at least, a man belonging to the upper class. But that, again, is only an impression.’

‘What has led you to form it?’

‘Well—the greasy cap, the common handkerchief, and the marks of the rough boots on the floor,’ he replied.

‘I understand,’ I said; ‘murderers don’t leave traces behind them which tell the truth.’

‘We shall make something out of you yet, my dear Sainclair,’ concluded Rouletabille.

CHAPTER III

‘A MAN HAS PASSED LIKE A SHADOW THROUGH THE BLINDS’

HALF an hour later Rouletabille and I were on the platform of the Orleans station, awaiting the departure of the train which was to take us to Epinay-sur-Orge.

On the platform we found Monsieur de Marquet and his Registrar, who represented the Judicial Court of Corbeil. Monsieur Marquet had spent the night in Paris, attending the final rehearsal, at the Scala, of a little play of which he was the unknown author, signing himself simply ‘Castigat Ridendo’.

Monsieur de Marquet was beginning to be a ‘noble old gentleman’. Generally he was extremely polite and full of gay humour, and in all his life had had but one passion—that of dramatic art. Throughout his magisterial career he was interested solely in cases capable of furnishing him with something in the nature of a drama. Though he might very well have aspired to the highest judicial positions, he had never really worked for anything but to win a success at the romantic Porte-Saint-Martin, or at the sombre Odéon.

Because of the mystery which shrouded it, the case of the Yellow Room was certain to fascinate so theatrical a mind. It interested him enormously, and he threw himself into it, less as a magistrate eager to know the truth, than as an amateur of dramatic embroglios, tending wholly to mystery and intrigue, who dreads nothing so much as the explanatory final act.

So that, at the moment of meeting him, I heard Monsieur de Marquet say to the Registrar with a sigh:

‘I hope, my dear Monsieur Maleine, this builder with his pickaxe will not destroy so fine a mystery.’

‘Have no fear,’ replied Monsieur Maleine, ‘his pickaxe may demolish the pavilion, perhaps, but it will leave our case intact. I have sounded the walls and examined the ceiling and floor and I know all about it. I am not to be deceived.’

Having thus reassured his chief, Monsieur Maleine, with a discreet movement of the head, drew Monsieur de Marquet’s attention to us. The face of that gentleman clouded, and, as he saw Rouletabille approaching, hat in hand, he sprang into one of the empty carriages saying, half aloud to his Registrar, as he did so, ‘Above all, no journalists!’

Monsieur Maleine replied in the same tone, ‘I understand!’ and then tried to prevent Rouletabille from entering the same compartment with the examining magistrate.

‘Excuse me, gentlemen—this compartment is reserved.’

‘I am a journalist, Monsieur, engaged on the Epoque,’ said my young friend with a great show of gesture and politeness, ‘and I have a word or two to say to Monsieur de Marquet.’

‘Monsieur is very much engaged with the inquiry he has in hand.’

‘Ah! His inquiry, pray believe me, is absolutely a matter of indifference to me. I am no scavenger of odds and ends,’ he went on, with infinite contempt in his lower lip, ‘I am a theatrical reporter; and this evening I shall have to give a little account of the play at the Scala.’

‘Get in, sir, please,’ said the Registrar.

Rouletabille was already in the compartment. I went in after him and seated myself by his side. The Registrar followed and closed the carriage door.

Monsieur de Marquet looked at him.

‘Ah, sir,’ Rouletabille began, ‘You must not be angry with Monsieur de Maleine. It is not with Monsieur de Marquet that I desire to have the honour of speaking, but with Monsieur ‘Castigat Ridendo.’ Permit me to congratulate you—personally, as well as the writer for the Epoque.’ And Rouletabille, having first introduced me, introduced himself.

Monsieur de Marquet, with a nervous gesture, caressed his beard into a point, and explained to Rouletabille, in a few words, that he was too modest an author to desire that the veil of his pseudonym should be publicly raised, and that he hoped the enthusiasm of the journalist for the dramatist’s work would not lead him to tell the public that Monsieur ‘Castigat Ridendo’ and the examining magistrate of Corbeil were one and the same person.