Полная версия

The Judgement of Strangers

She smiled back. ‘It’s odd, isn’t it? It’s not just us getting married. It’s our friends and relations as well.’

In January, Rosemary went back to school. Vanessa spent the following Saturday with me. Now we had the house to ourselves, we wanted to plan what changes would have to be made when Vanessa moved in; we had thought it would be tactless to do this while Rosemary was there. After lunch, the doorbell rang. I was not surprised to find Audrey Oliphant on the doorstep.

She wore a heavy tweed suit, rather too small for her, and a semi-transparent plastic mac, which gave her an ill-defined, almost ghostly appearance.

‘So sorry to disturb you,’ she said. ‘I wondered if you’d seen Lord Peter recently.’

Vanessa came out of the kitchen and said hello.

‘Lord Peter – my cat,’ Audrey explained to her. ‘Such a worry. He treats the Vicarage as his second home.’

I leant nonchalantly against the door, preventing her from stepping into the hall. ‘I’m afraid we haven’t seen him.’

‘The kettle’s on,’ Vanessa said. ‘Would you like a cup?’

Audrey slipped past me and followed her into the kitchen. ‘Lord Peter has to cross the main road to get here. The traffic’s getting worse and worse, especially since they started work on the motorway.’

‘Cats are very good at looking after themselves,’ Vanessa said.

‘I hope I’m not disturbing you.’ No doubt accidentally, Audrey tried to insinuate a hint of indecency, the faintest wiggle of the eyebrows, into this possibility. ‘I’m sure you were in the middle of something.’

‘Nothing that wasn’t going to wait until after tea,’ Vanessa said. ‘How’s the book selling?’

‘Splendidly, thank you. We sold sixty-three copies over Christmas. I knew people would like it.’

‘Why don’t you take Audrey’s coat?’ Vanessa suggested to me.

‘People like to know about their own village,’ Audrey continued, allowing me to peel her plastic mac away from her. ‘I know there have been changes, but Roth really is a village still.’

Changes? A village? I thought of the huge reservoir to the north, of the projected motorway through the southern part of the parish, and of the sea of suburban houses that lapped around the green. I carried the tea tray into the sitting room.

‘There’s not much of it left,’ Vanessa said. ‘The village, I mean.’

Audrey stared at Vanessa. ‘Oh, you’re quite wrong. Let me show you.’ She beckoned Vanessa towards the window, which looked out over the drive, the road and the green. ‘That’s the village.’ She nodded to her left, towards the houses of Vicarage Drive. ‘Here and on the left: the Vicarage and its garden. And then on our right is St Mary Magdalene, and beyond that the gates to Roth Park and the river. If you cross the stone bridge and carry on down the road, we’ll come to the Old Manor House, where Lady Youlgreave lives.’

‘I must take you to meet Lady Youlgreave,’ I said to Vanessa, attempting to divert the flow. ‘In a sense she’s my employer.’

It was no use. Audrey had now turned towards the green and was pointing at Malik’s Minimarket, which stood just beside the main road at the western end of the north side of the green.

‘That was the village forge when I was a girl.’ She laughed, a high and irritating sound. Her voice acquired a faint sing-song cadence. ‘Of course, it’s changed a bit since then, but haven’t we all? And beside it is my little home, Tudor Cottage. (I was born there, you know, on the second floor. The window on the left.) Then there’s the Queen’s Head. I think part of their cellars are even older than Tudor Cottage.’

We all stared at the Queen’s Head, a building that had been modernized so many times in the last hundred years that it had lost all trace of its original character. The pub now had a restaurant which served steaks, chips and cheap wine. At the weekend, the disco in the basement attracted young people from miles around, and there were regular complaints – usually from Audrey – about the noise.

‘The bus shelter wasn’t there when I was a girl,’ Audrey went on. ‘We had a much nicer one, with a thatched roof.’

The bus shelter stood on the green itself, opposite the pub. It was a malodorous cavern, whose main use was as the wet-weather headquarters of the teenagers who lived on the Manor Farm council estate.

‘And of course Manor Farm Lane has seen one or two changes as well.’ Audrey pointed at the road to the council estate which went off at the north-east corner of the green and winced theatrically. ‘We used to have picnics by the stream beyond the barn,’ she murmured in a confidential voice. ‘Just over there. Wonderful wild flowers in the spring.’

The barn was long gone, and the stream had been culverted over. Yet she gave the impression that for her they were still vivid, in a way that the council estate was not. For her the past inhabited the present and gave it meaning.

The finger moved on to the east side of the green, to a nondescript row of villas from the 1930s, defiantly suburban, to the library and the ramshackle church hall. ‘There was a lovely line of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cottages over there.’

Vanessa’s eyes met mine. I opened my mouth, but I was too late. Audrey’s head had swivelled round to the south side, to the four detached Edwardian houses whose gardens ran down to the Rowan behind them. Two of them had been cut up into flats; one was leased as offices; and the fourth was where Dr Vintner lived with his family and had his surgery.

‘A retired colonel in the Bengal Lancers used to live in the one at the far end. There was a nice solicitor in Number Two. And the lady in Number Three was some sort of cousin of the Youlgreaves.’

Black fur streaked along the windowsill. A paw tapped the glass. Lord Peter had come to join us.

‘Oh look!’ Audrey said. ‘Isn’t he clever?’ She bent down, bringing her head level with Lord Peter’s. ‘You knew Mummy was coming to look for you, didn’t you? So you came to find Mummy instead.’

8

In February, Lady Youlgreave demanded to see Vanessa. She invited us to have a glass of sherry with her after church on Sunday.

When I told Vanessa, her face brightened. ‘Oh good.’

‘I wish she’d chosen some other time.’ Sunday was my busiest day.

‘Do you want to see if we can rearrange it?’

‘It would be diplomatic to go,’ I said. ‘No sense in upsetting her.’

‘I’ll take you out to lunch afterwards. As a reward.’

‘Why are you so keen to meet her?’

‘Not exactly keen. Just interested.’

‘Because of the connection with Francis Youlgreave?’

Vanessa nodded. ‘It’s not every day you have a chance to meet the surviving family of a dead poet.’ She glanced at me, her face mischievous. ‘Or for that matter the man responsible for the care of his earthly remains.’

‘No doubt that was the only reason you wanted to marry me?’

‘Beggars can’t be choosers. Anyway, I want to meet Lady Youlgreave for her own sake. Isn’t she your boss?’

The old woman was the patron of the living, which meant that on the departure of one incumbent she had the right to nominate the next. The practice was a quaint survival from the days when such patronage had been a convenient way to provide financially for younger sons. In practice, such private patrons usually delegated the choice to the bishop. But Lady Youlgreave had chosen to exercise the right when she nominated me. An ancient possessiveness lingered. Though she rarely came to church, I had heard her refer to me on more than one occasion as ‘my vicar’.

On Sunday, swathed in coats, Vanessa and I left the Vicarage. We walked arm in arm past the railings of the church and crossed the mouth of the drive to Roth Park. The big wrought-iron gates had stood open for as long as anyone could remember. Each gate contained the letter Y within an oval frame. On the top of the left-hand gatepost was a stone fist brandishing a dagger, the crest of the Youlgreaves. On the right-hand gatepost there was nothing but an iron spike.

‘What happened to the other dagger?’ Vanessa asked.

‘According to Audrey, some teddy boys pulled it down on New Year’s Eve. Before my time.’

Vanessa stopped, staring up the drive, a broad strip of grass and weeds separating two ruts of mud and gravel, running into a tunnel of trees which needed pollarding. The house could not be seen from the road.

‘It looks so mournful,’ she said.

‘The Bramleys haven’t spent much money on the place. I’m told they’re trying to sell it.’

‘Is there much land left?’

‘Just the strip along the drive, plus a bit near the house. Most of it was sold off for housing.’

‘Sometimes it all seems so pointless. Spending all that time and money on a place like that.’

I glanced at the gates. ‘How old are they, do you think?’

‘Turn of the century? Obviously made to last for generations.’

‘Designed to impress. And the implication was that the house and the park would be in your descendants’ hands for ever and ever.’

‘That’s what’s so sad,’ Vanessa said. ‘They were building for eternity, and seventy years later eternity came to an end.’

‘Eternity was even shorter than that. The Youlgreaves had to sell up in the nineteen-thirties.’

‘I remember. It was in Audrey’s book. And they hadn’t been here for very long, had they? Not in dynastic terms.’

We walked across the bridge. A lorry travelling north from the gravel pits splashed mud on my overcoat. Vanessa peered down at the muddy waters beneath. The Rowan was no more than a stream, but at this point, though shallow, it was relatively wide.

We came to the Old Manor House, a long low building separated from the road by a line of posts linked by chains. This side of the house had a two-storey frontage with six bays. The windows were large and Georgian. At some point the facade had been rendered and painted a pale greeny-blue, now fading and flaking with age. There were darker stains on the walls where rainwater had cascaded out of the broken guttering.

Between the posts and the house was a circular lawn, around which ran the drive. The grass was long and lank, and there were drifts of leaves against the house. Weeds sprouted through the cracks of the tarmac. In the middle of the lawn was a wooden bird table, beneath which sat Lord Peter, waiting. Hearing our footsteps, the cat glanced towards us and moved away without hurrying. He slithered through the bars of the gate at the side of the house and slid out of sight behind the dustbins.

‘That cat’s everywhere,’ Vanessa said. ‘Don’t you find it sinister?’

I glanced at her. ‘No. Why?’

‘No reason.’ She looked away. ‘Is that someone waving from the window? The one at the end?’

An arm was waving slowly behind the ground-floor window to the far left. We walked towards the front door.

‘How do you feel about dogs, by the way?’

‘Fine. Why?’

‘Lady Youlgreave has two of them.’

I tried the handle of the front door. It was locked. There was a burst of barking from the other side. I felt Vanessa recoil.

‘It’s all right. They’re tied up. We’ll have to go round to the back.’

We walked down the side of the house, past the dustbins and into the yard at the rear. There was no sign of Lord Peter. The spare key was hidden under an upturned flowerpot beside the door.

‘A little obvious, isn’t it?’ Vanessa said. ‘It’s the first place anyone would look.’

We let ourselves into a scullery which led through an evil-smelling kitchen towards the sound of barking in the hall.

Beauty and Beast were attached by their leads to the newel post at the foot of the stairs. Beauty was an Alsatian, so old she could hardly stand up, and almost blind. Beast was a dachshund, even older, though she retained more of her faculties. She, too, had her problems in the shape of a sausage-shaped tumour that dangled from her belly almost to the floor. When she waddled along, it was as though she had five legs. When I had first come to Roth, the dogs and their owner had been much more active, and one often met the three of them marching along the footpaths that criss-crossed what was left of Roth Park. Now their lives had contracted. The dogs were no longer capable of guarding or attacking. They ate, slept, defecated and barked.

‘This way,’ I said to Vanessa, raising my voice to make her hear above the din.

She wrinkled her nose and mouthed, ‘Does it always smell this bad?’

I nodded. Doris Potter, who was one of my regular communicants, came in twice a day during the week, and an agency nurse covered the weekends. But they were unable to do much more than look after Lady Youlgreave herself.

The hall was T-shaped, with the stairs at the rear. I led the way into the right-hand arm of the T. I tapped on a door at the end of the corridor.

‘Come in, David.’ The voice was high-pitched like a child’s.

The room had once been a dining room. When I had first come to Roth, Lady Youlgreave had asked me to dinner, and we had eaten by candlelight, facing each other across the huge mahogany table. Then as now, most of the furniture was Victorian, and designed for a larger room. We had eaten food which came out of tins and we drank a bottle of claret which should have been opened five years earlier.

For an instant, I saw the room afresh, as if through Vanessa’s eyes. I noticed the thick grey cobwebs around the cornices, a bird’s nest among the ashes in the grate, and the dust on every horizontal surface. Time had drained most of the colour and substance from the Turkish carpet, leaving a ghostly presence on the floor. The walls were crowded with oil paintings, none of them particularly old and most of them worth less than their heavy gilt frames. The exception was the Sargent over the fireplace: it showed a large, red-faced man in tweeds, Lady Youlgreave’s father-in-law, standing beside the Rowan with his large red house in the background and a springer spaniel at his feet.

Our hostess was sitting in an easy chair beside the window. This was where she usually passed her days. She spent her nights in the room next door, which had once been her husband’s study; she no longer used the upstairs. She had a blanket draped over her lap and a side table beside the chair. A Zimmer frame stood within arm’s reach. There were books on the side table, and also a lined pad on a clipboard. On a low stool within reach of the chair was a metal box with its lid open.

For a moment, Lady Youlgreave stared at us as we hesitated in the doorway. It was as though she had forgotten what we were doing here. The dogs were still barking behind us, but with less conviction than before.

‘Shut the door and take off your coats,’ she said. ‘Put them down. Doesn’t matter where.’

Lady Youlgreave had been a small woman to begin with, and now old age had made her even smaller. Dark eyes peered up at us from deep sockets. She was wearing a dress of some stiff material with a high collar; the dress was too large for her now, and her head poked out of the folds of the collar like a tortoise’s from its shell.

‘Well,’ she said. ‘This is a surprise.’

‘I’d like to introduce Vanessa Forde, my fiancée. Vanessa, this is Lady Youlgreave.’

‘How do you do. Pull up one of those chairs and sit down where I can see you.’

I arranged two of the dining chairs for Vanessa and myself. The three of us sat in a little semi-circle in front of the window. Vanessa was nearest the box, and I noticed her glancing into its open mouth.

Lady Youlgreave studied Vanessa with unabashed curiosity. ‘So. If you ask me, David’s luckier than he deserves.’

Vanessa smiled and politely shook her head.

‘My cleaning woman tells me you’re a publisher.’

‘Yes – by accident really.’

‘I dare say you’ll be giving it up when you marry.’

‘No.’ Vanessa glanced at me. ‘It’s my job. In any case, the income will be important.’

Lady Youlgreave squeezed her lips together. Then she relaxed them and said, ‘In my day, a husband supported a wife.’

‘I suppose I’ve grown used to supporting myself.’

‘And a wife supported her husband in other ways. Made a home for him.’ Unexpectedly, she laughed, a bubbling hiss from the back of her throat. ‘And in the case of a vicar’s wife, she usually ran the parish as well. You’ll have plenty to do here without going out to work.’

‘It’s up to Vanessa, of course,’ I said. ‘By the way, how are you feeling?’

‘Awful. That damned doctor keeps giving me new medicines, but all they do is bung me up and give me bad dreams.’ She waved a brown, twisted hand at the box on the stool. ‘I dreamt about that last night. I dreamt I found a dead bird inside. A goose. Told the girl I wanted it roasted for lunch. Then I saw it was crawling with maggots.’ There was another laugh. ‘That’ll teach me to go rummaging through the past.’

‘Is that what you’ve been doing?’ Vanessa asked. ‘In there?’

‘I have to do something. I never realized you can be tired and in pain and bored – all at the same time. The girl told me that the Oliphant woman had written a history of Roth. So I made her buy me a copy. Not as bad as I thought it was going to be.’ She glared at me. ‘I suppose you had a hand in it.’

‘Vanessa and I edited it, yes, and Vanessa saw it through the press.’

‘Thought so. Anyway, it made me curious. I knew there was a lot of rubbish up in the attic. Papers, and so on. George had them put up there when we moved from the other house. Said he was going to write the family history. God knows why. Literature wasn’t his line at all. Didn’t know one end of a pen from another. Anyway, he never had the opportunity. So all the rubbish just stayed up there.’

Vanessa leant forwards. ‘Do you think you might write something yourself?’

Lady Youlgreave held up her right hand. ‘With fingers like this?’ She let the hand drop on her lap. ‘Besides, what does it matter? It’s all over with. They’re all dead and buried. Who cares what they did or why they did it?’

She stared out of the window at the bird table. I wondered if the morphine were affecting her mind. James Vintner had told me that he had increased the dose recently. Like the house and the dogs, their owner was sliding into decay.

I said, ‘Vanessa’s read quite a lot of Francis Youlgreave’s verse.’

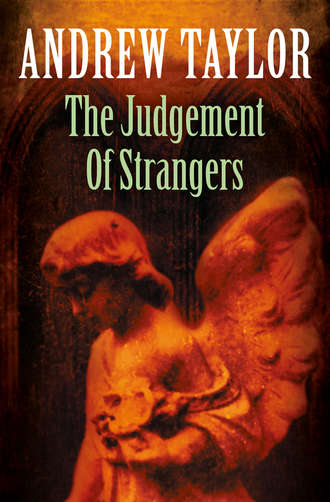

‘I’ve got a copy of The Four Last Things,’ Vanessa said. ‘The one with “The Judgement of Strangers” in it.’

Lady Youlgreave stared at her for a moment. ‘There were two other collections, The Tongues of Angels and Last Poems. He published Last Poems when he was still up at Oxford. Silly man. So pretentious.’ Her eyes moved to me. ‘Pass me that book,’ she demanded. ‘The black one on the corner of the table.’

I handed her a quarto-sized hardback notebook. The seconds ticked by while she opened it and tried to find the page she wanted. Vanessa and I looked at each other. Inside the notebook I saw yellowing paper, unlined and flecked with damp, covered with erratic lines of handwriting in brown ink.

‘There,’ Lady Youlgreave said at last, placing the open notebook on her side table and turning it so it was the right way up for Vanessa and me. ‘Read that.’

The handwriting was a mass of blots and corrections. Two lines leapt out at me, however, because they were the only ones which had no alterations or blemishes:

Then darkness descended; and whispers defiled

The judgement of stranger, and widow, and child.

‘Is that his writing?’ Vanessa asked, her voice strained.

Lady Youlgreave nodded. ‘This is a volume of his journal. March eighteen-ninety-four, while he was still in London.’ The lips twisted. ‘He was the vicar of St Michael’s in Beauclerk Place. I think this was the first draft.’ She looked up at us, at our eager faces, then slowly closed the book. ‘According to this journal, it was a command performance.’

Vanessa raised her eyebrows. ‘I don’t understand.’

Lady Youlgreave drew the book towards her and clasped it on her lap. ‘He wrote the first half of the first draft in a frenzy of inspiration in the early hours of the morning. He had just had an angelic visitation. He believed that the angel had told him to write the poem.’ Once more her lips curled and she looked from me to Vanessa. ‘He was intoxicated at the time, of course. He had been smoking opium earlier that evening. He used to patronize an establishment in Leicester Square.’ Her head swayed on her neck. ‘An establishment which seems to have catered for a variety of tastes.’

‘Are there many of his journals?’ asked Vanessa. ‘Or manuscripts of his poems? Or letters?’

‘Quite a few. I’ve not had time to go through everything yet.’

‘As you know, I’m a publisher. I can’t help wondering if you might have the material for a biography of Francis Youlgreave there.’

‘Very likely. For example, his journal gives a very different view of the Rosington scandal. From the horse’s mouth, as it were.’ Her lips twisted and she made a hissing sound. ‘The trouble is, this particular horse isn’t always a reliable witness. George’s father used to say – but I mustn’t keep you waiting like this. You haven’t had any sherry yet. I’m sure we’ve got some somewhere.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said.

‘The girl will know. She’s late. She should be bringing me my lunch.’

The heavy eyelids, like dough-coloured rubber, drooped over the eyes. The fingers twitched, but did not relax their hold of Francis Youlgreave’s journal.

‘I think perhaps we’d better be going,’ I said. ‘Leave you to your lunch.’

‘You can give me my medicine first.’ The eyes were fully open again and suddenly alert. ‘It’s the bottle on the mantelpiece.’

I hesitated. ‘Are you sure it’s the right time?’

‘I always have it before lunch,’ she snapped. ‘That’s what Dr Vintner said. It’s before lunch, isn’t it? And the girl’s late. She’s supposed to be bringing me my lunch.’

There was a clean glass and a spoon beside the bottle on the mantelpiece. I measured out a dose and gave her the glass. She clasped it in both hands and drank it at once. She sat back, still cradling the glass. A dribble of liquid ran down her chin.

‘I’ll leave a note,’ I said. ‘Just to say that you’ve had your medicine.’

‘But there’s no need to write a note. I’ll tell Doris myself.’

‘It won’t be Doris,’ I said. ‘It’s the weekend, so it’s the nurse who’ll come in.’

‘Silly woman. Thinks I’m deaf. Thinks I’m senile. Anyway, I told you: I’ll tell her myself.’

I could be obstinate, too. I scribbled a few words in pencil on a page torn from my diary and left it under the bottle for the nurse. Lady Youlgreave barely acknowledged us when we said goodbye. But when we were almost at the door, she stirred.

‘Come and see me again soon,’ she commanded. ‘Both of you. Perhaps you’d like to look at some of Uncle Francis’s things. He was very interested in sex, you know.’ She made a hissing noise again, her way of expressing mirth. ‘Just like you, David.’

9

Vanessa and I were married on a rainy Saturday in April. Henry Appleyard was my best man. Michael gave us a present, a battered but beautiful seventeenth-century French edition of Ecclesiasticus; according to the bookplate it had once been part of the library of Rosington Theological College.

‘It was his own idea,’ his mother whispered to me. ‘His own money, too. Quite a coincidence – Rosington, I mean.’

‘I hope it wasn’t expensive.’

‘Five shillings. He found it in a junk shop.’

‘We’ve been very lucky with presents,’ Vanessa said. ‘Rosemary gave us a gorgeous coffee pot. Denbigh ware.’

It was only then that I realized Rosemary was listening intently to the conversation. Later I noticed her examining the book, flicking through the pages as if they irritated her.

Vanessa and I flew to Italy the same afternoon. She had arranged it all, including the pensione in Florence where we were to stay. I had assumed that if we had a honeymoon at all it would be in England. But Florence had been Vanessa’s idea, and she was so excited about it that I did not have the heart to try to change her mind. Her plan had support from an unexpected quarter: when I told Peter Hudson, he said, ‘She’s right. Get right away from everything. You owe it to each other.’