Полная версия

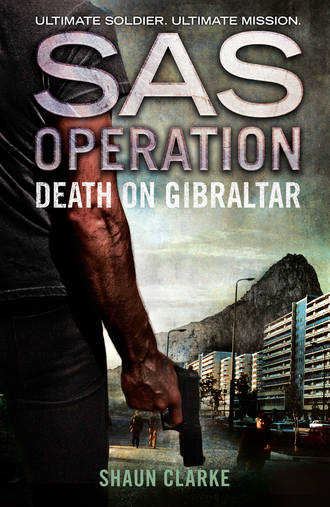

Death on Gibraltar

Death on Gibraltar

SHAUN CLARKE

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 22 Books/Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Copyright © Bloomsbury Publishing plc 1994

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover Photographs © Nik Keevil/Arcangel Images (man); Ulstein bild/Getty Images (street scene); Shutterstock.com (textures)

Shaun Clarke asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction based on a factual event. The real names of the three IRA terrorists shot dead on Gibraltar on 8 March 1988 have been retained, as have those of the eight IRA men killed at Loughgall, Northern Ireland, on 8 May the previous year. Many events are partially or wholly the work of the author’s imagination; all other names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are wholly the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to other actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008155308

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008155315

Version: 2015-10-29

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prelude

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Postscript

OTHER TITLES IN THE SAS OPERATION SERIES

About the Publisher

Prelude

On the evening of Thursday 7 May 1987 fifteen soldiers from G Squadron, SAS, all dressed in standard DPM windproof, tight-weave cotton trousers and olive-green cotton battle smocks with British Army boots and maroon berets, were driven in four-wheel-drive Bedford lorries from their base at Stirling Lines, Hereford, to RAF Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, where they boarded a Hercules C-130 transport plane.

The men were armed with L7A2 7.62mm general-purpose machine-guns (GPMGs), 7.62mm Heckler & Koch G3-A4K twenty-round assault rifles with LE1-100 laser sights, and 5.56mm M16 thirty-round Armalite rifles. They also had many attachments for the various weapons, including bipods, telescopic sights, night-vision aids, and M203 40mm grenade-launchers. The ubiquitous standard-issue 9mm Browning High Power handgun was holstered at each man’s hip. Their personal kit, including ammunition, water, rations, a medical pack, and spare clothing and batteries, was packed in the square-frame Cyclops bergens on their backs. Finally, they had with them crates filled with various items of high-tech communications and surveillance equipment, including Nikon F-801 35mm SLR cameras with Davies Minimodulux hand-held image intensifiers for night photography, a PRC319 microprocessor-based tactical radio, Pace Communications Ltd Landmaster III hand-held transceivers and Radio Systems Inc. walkie-talkies.

From RAF Brize Norton, the men were flown to RAF Aldergrove in Belfast, where they were transferred with their kit to three unmarked Avis vans and then driven through the rolling green countryside to the Security Forces base built around the old mill in the village of Bessbrook. There they were united with the twenty-four SAS men already serving in Northern Ireland, making a total force of thirty-nine specially trained and experienced counter-terrorist troopers.

The next morning was spent in a draughty lecture hall in the SF base where, with the aid of maps and a scale model of the Royal Ulster Constabulary police station of Loughgall, the combined body of men were given a final briefing on the operation to come.

Early that afternoon, when the RUC had thrown a discreet cordon around the area, diverting traffic and keeping all but local people out, the SAS men, with their weapons and surveillance equipment, were transported in the rented vans to Loughgall. Small and mostly Protestant, Loughgall is surrounded by the rolling green hills and apple trees of the ‘orchard country’ of north Armagh. It is some eight miles from Armagh city, and the road which leads from Armagh slopes down into the village, passing a walled copse on the right. The RUC station is almost opposite, between a row of bungalows, a former Ulster Defence Regiment barracks, the football team’s clubhouse and a small telephone exchange. It is small enough to be run by a sergeant and three or four officers, and unimportant enough to be open only limited hours in the morning and afternoon, always closing completely at 7 p.m.

That day, well before the ‘barracks’, as the RUC station is known locally, was closed, some of the SAS men entered the building to occupy surveillance and firing positions at the rear and front, those at the front keeping well away from one particular side. While they were taking up positions inside, the rest were dividing into separate groups to set up ambushes around the building.

Two GPMG teams moved into the copse overlooking the police station, which enabled them to cover the football pitch facing it on the other side of the Armagh road. Others took up positions closer to and around the building, and behind the blast-proof wall protecting the front door.

Another team took the high ground overlooking the rear of the building. The remainder assumed positions in which they could act as cordon teams staking out the approach road in both directions.

Meanwhile, as members of the RUC’s Headquarters Mobile Support Units were deployed in the vicinity, companies of UDR and British Army soldiers, as well as mobile police squads, were ready to cordon off the area after the operation.

That same afternoon a group of masked men hijacked a blue Toyota Hiace van at gunpoint from a business in Mountjoy Road, Dungannon. Sometime after five o’clock the same group hijacked a mechanical digger from a Dungannon farm, and the vehicle was driven to another farmyard about nine miles north of Loughgall.

With the SAS in position inside the RUC station, the building was locked up at the usual time. The troopers dug in around it had melted into the scenery, and apart from the sound of the wind, there was absolute silence.

Just before seven o’clock that evening, in the farmhouse north of Loughgall, close to the Armagh–Tyrone border and the Republican strongholds of Washing Bay and Coalisland, an IRA ‘bucket bomb’ team carefully loaded a 200lb bomb – designed to be set off by lighting a simple fuse – on to the bucket of the hijacked mechanical digger. Waiting close by, and watching them nervously, was a support team consisting of two Active Service Units of the East Tyrone Brigade of the IRA. Inside their stolen van was a collection of weapons that included three Heckler & Koch G3 7.62mm assault rifles, two 5.56mm FNC rifles, an assault shotgun and a German Ruger revolver taken from one of the reserve constables shot dead during a raid at Ballygawley eighteen months earlier.

Of the three-man bucket bomb team, one was a twenty-one-year-old with five years’ IRA service, including several spells of detention; another had six years in the IRA behind him and had been arrested and interrogated many times because of it; and the third had twelve years’ IRA service and six years’ imprisonment.

The leader of one ASU team was thirty-year-old Patrick Kelly. Though known to be almost rigidly puritanical about his family and religious faith, Kelly was the commander of East Tyrone Provisional IRA units and suspected of murdering two RUC officers. The other ASU team was led by thirty-one-year-old Jim Lynagh, a former Sinn Fein councillor with fifteen years in the IRA and various terms in prison to his name. Though Lynagh, in direct contrast to Kelly, was an extrovert, good-humoured personality, he was suspected of many killings and, though acquitted of assassinating a UDR soldier, was widely believed to have done the deed.

The rest of the ASU teams consisted of a thirty-two-year-old escaper from the Maze Prison with fifteen years’ violent IRA service to his credit; a nineteen-year-old who had been in the IRA for three years and claimed that he had been threatened with assassination by the RUC; and a twenty-five-year-old who had been in the IRA for five years, had been arrested many times and was a veteran of many terrorist operations.

These eight men were hoping to repeat the success of a similar attack they had carried out eighteen months earlier at Ballygawley, when they had shot their way into the police station, killing two officers, and then blown up the building.

This time, however, as they loaded their bomb on to the digger, they were being watched by a police undercover surveillance team, Special Branch’s E4A, which was transmitting reports of their movements to the SAS men located in and around Loughgall RUC station.

The five armed men accompanying the three bombers had initially come along to ensure that no RUC men would escape through the back door of the building, as they had done at Ballygawley. However, just before climbing into their unmarked van, the two team leaders, Kelly and Lynagh, appeared – at least to the distant observers of E4A – to become embroiled in some kind of argument. Though what they said is not known, the argument was later taken by the Security Forces to be a sign of a last-minute confusion that could explain why, by the time the terrorists reached Loughgall in the stolen Toyota, their original plan for covering the back of the RUC police station had been dropped and they prepared to attack only the unguarded side of the building. Ironically, by ignoring the rear of the building, they were repeating the mistake they had made eighteen months earlier.

Their plan was to ignite the fuse on the bomb, then ram the RUC station with the bomb still in the bucket of the digger. They chose the side of the building because of the protection afforded the front entrance by the blast-proof wall. As an alternative to the usual attacks with heavy mortars or RPG7 rockets, this tactic had first been attempted eighteen months earlier at Ballygawley, then again, nine months later, at the Birches, Co. Tyrone, only five miles from Loughgall. Both operations had been successful.

To avoid the Security Forces, the terrorists travelled from the farmyard to Loughgall via the narrow, winding side lanes, rather than taking the main Dungannon-Armagh road. The five-man support team were in the blue van, driven by Seamus Donnelly, with one of the team leaders, Lynagh, in the back and Kelly in the front beside the driver. The van was in the lead to enable Kelly to check that the road ahead was clear. The mechanical digger followed, driven by Declan Arthurs and with Tony Gormley and Gerard O’Callaghan ‘riding shotgun’, though with their weapons concealed. The bucket bomb was hidden under a pile of rubble.

While the terrorists thought they were avoiding the Security Forces, their movements were almost certainly observed at various points along the route by surveillance teams in unmarked ‘Q’ cars or covert observation posts.

The Toyota van passed through Loughgall village at a quarter past seven. SAS men were hiding behind the wall of the church as it drove past them, but they held their fire. They wanted the van and mechanical digger to reach the police station as this would give the SAS men inside an excuse to open fire in ‘self-defence’.

At precisely 7.20 p.m., possibly trying to ascertain if anyone was still in the building, Arthurs drove the mechanical digger to and fro a few times, with Gormley and O’Callaghan now deliberately putting their weapons on view. What happened next is still in dispute.

As the terrorists all knew that the Loughgall RUC station was empty from seven o’clock every evening, their timing of the attack is surely an indication that their purpose was to destroy the building, not take lives. More importantly, it begs the question of why the ASU team leader, Patrick Kelly, a very experienced and normally astute IRA fighter, would do what he is reported to have done.

Though believing that the police station was empty, Kelly climbed out of the cabin of the Toyota van with the driver, Donnelly, and proceeded to open fire with his assault rifle on the front of the building. Donnelly and some of the others then did the same.

Instantly, the SAS ambush party inside the building opened fire with a fearsome combination of 7.62mm Heckler & Koch G3-A4K assault rifles and 5.56mm M16 Armalites, catching the terrorists in a devastating fusillade, perforating the rear and side of the van with bullets and mowing down some of the men even before the 7.62mm GPMGs in the copse had roared into action, peppering the front of the van and catching the remaining terrorists in a deadly crossfire.

Hit several times, Kelly fell close to the cabin of the van with blood spreading out around him from a fatal head wound. Realizing what was happening, the experienced Jim Lynagh and Patrick McKearney scurried back into the van, but died in a hail of bullets that tore through its side panel. Donnelly had scrambled back into the driver’s seat, but was mortally wounded in the same rain of bullets before he could move off. After ramming the mechanical digger into the side of the building, the driver, Arthurs, and another terrorist, Eugene Kelly, died as they tried in vain to take cover behind the bullet-riddled Toyota.

Even as the driver of the mechanical digger was dying in a hail of bullets, O’Callaghan was igniting the fuse of the 200lb bomb with a Zippo lighter. He then took cover beside Gormley.

The roar of the exploding bomb drowned out even the combined din of the GPMGs, assault rifles and Armalites. The spiralling dust and boiling smoke eventually settled down to reveal that the explosion had blown away most of the end of the RUC station nearest the gate, demolished the telephone exchange next door, and showered the football clubhouse with raining masonry. The mechanical digger had been blown to pieces and one of its wheels had flown about forty yards, to smash through a wooden fence and land on the football pitch. Some of the police and SAS men inside the building had been injured by the blast and flying debris.

When the bomb went off, Gormley and O’Callaghan tried to run for cover, but Gormley was cut down by heavy SAS gunfire as he emerged from behind the wall where he had taken cover. O’Callaghan was cut to pieces as he ran across the road from the badly damaged building.

But the IRA men were not the only casualties.

Because the GPMG teams hidden in the copse were targeting a building that stood close to the Armagh road, the oblique direction of fire meant that they also fired many rounds into the football pitch opposite and into parts of the village, including the wall of the church hall, where children were playing at the time. In addition, three civilian cars were passing between the RUC station and the church as the battle commenced.

Driving in a white Citroën past the church and down the hill towards the police station, Oliver Hughes, a thirty-six-year-old father of three, and his brother Anthony heard the thunderclap of the massive bomb, braked to a halt immediately and started to reverse the car. Unfortunately, both men were in overalls similar to those worn by the terrorists, so the SAS soldiers hidden near the church, assuming they were terrorist reinforcements, opened fire, peppering the Citroën with bullets, killing Oliver Hughes outright and badly wounding his brother, who took three rounds in the back and one in the head.

Travelling in the opposite direction, up the hill towards the church, another car, containing a woman and her young daughter, was also sprayed with bullets and screeched to a halt. In this instance, before anyone was killed the commander of one of the SAS groups raced through the hail of bullets to drag the woman and her daughter out of the car to safety. Miraculously, he succeeded.

The third car contained an elderly couple, Mr and Mrs Herbert Buckley. Both jumped out of their car and threw themselves to the ground, to survive unscathed.

Another motorist, a brewery salesman, had stopped his car even closer to the main action – between the IRA’s Toyota and the copse where the two GPMG crews were dug in – and looked on in stunned disbelief as a rain of GPMG bullets hit the blue van. During a lull in the firing, he jumped out of his car and ran to find shelter behind the bungalows next to the police station. He never reached them, for after being rugby-tackled by an SAS trooper, he was held in custody until his identity could be established.

When the firing ceased, all eight of the IRA terrorists were found to be dead. Within thirty minutes, even as British Gazelle reconnaissance helicopters were flying over the area and British Army troops were combing the countryside in the vain pursuit of other terrorists, the SAS men were already being lifted out.

The deaths of the eight terrorists were the worst set-back the IRA had experienced in sixty years. During their funerals the IRA made it perfectly clear that bloody retaliation could be expected. It was a threat that could not be ignored by the British government.

1

‘It is the belief of our Intelligence chiefs,’ the man addressed only as ‘Mr Secretary’ informed the top-level crisis-management team in a basement office in Whitehall on 6 November 1987, ‘that the successful SAS ambush in Loughgall last May, which resulted in the deaths of eight leading IRA terrorists, will lead to an act of reprisal that’s probably being planned right now.’

There was a moment’s silence while the men sitting around the boardroom table took in what the Secretary was saying so gravely. This particular crisis-management team was known as COBR – it represented the Cabinet Office Briefing Room – and all those present were of considerable authority and power in various areas of national defence and security. Finally, after a lengthy silence, one of them, a saturnine, grey-haired man from British Intelligence, said: ‘If that’s the case, Mr Secretary, we should place both MI5 and MI6 on the alert and try to anticipate the most likely targets.’

‘Calling in MI5 is one thing,’ the Secretary replied, referring to the branch of the Security Service charged with overt counter-espionage. ‘But before calling in MI6, would someone please remind me of the reasoning behind what was obviously an exceptionally ambitious and contentious ambush.’

Everyone around the table knew just what he meant. MI6 was the secret intelligence service run by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. As its links with the FCO were never publicly acknowledged, it was best avoided when it came to operations that might end up with a high public profile – as, for instance, the siege of the Iranian Embassy in London in May 1980 had done.

‘The humiliation of the IRA,’ said the leader of the Special Military Intelligence Unit (SMIU) responsible for Northern Ireland. ‘That was the whole purpose of the Loughgall ambush.’

‘We’re constantly trying to humiliate the IRA,’ the Secretary replied, ‘but we don’t always go to such lengths. What made Loughgall so special?’

‘The assassination of the Lord Chief Justice and his wife the previous month,’ the SMIU leader replied, referring to the blowing up of the judge’s car by a 500lb bomb in the early hours of 25 April, when he and his wife were returning to their home in Northern Ireland after a holiday in the Republic. ‘As Northern Ireland’s most senior judge, he had publicly vowed to bring all terrorists to justice, so the terrorists assassinated him, not only as a warning to other like-minded judges, but as a means of profoundly embarrassing the British government, which of course it did.’

‘So the ambush at Loughgall was an act of revenge for the murder of the Lord Chief Justice and his wife?’

‘It was actually more than that, Mr Secretary,’ the SMIU man replied. ‘Within hours of the assassination of the Lord Chief Justice – that same evening, in fact – a full-time member of the East Tyrone UDR was murdered by two IRA gunmen while working in the yard of his own farm. That murder was particularly brutal. After shooting him in the back with assault rifles, in full view of his wife, the two gunmen stood over him where he lay on the ground and shot him repeatedly – about nineteen times in all. The East Tyrone IRA then claimed that they had carried out the killing.’

‘And that was somehow connected to the Loughgall ambush?’

‘Yes, Mr Secretary. We learnt from an informer that two ASU teams from East Tyrone were planning an attack on the RUC police station at Loughgall and that some of the men involved had been responsible for all three deaths.’

‘Was this informer known to be reliable?’

‘Yes, Mr Secretary, she was.’

‘And do we have proof that some of the IRA men who died at Loughgall were involved in the assassinations as she had stated?’

‘Again, the answer is yes. Ballistics tests on the Heckler & Koch G3 assault rifles and FNCs used by the IRA men at Loughgall proved that some of them were the same as those used to kill the UDR man.’

‘What about the Lord Chief Justice and his wife?’

‘For various reasons, including the reports of informants, we believe that the ASU teams involved in the attack at Loughgall were the same ones responsible for the deaths of the Lord Chief Justice and his wife. However, I’ll admit that as yet we have no conclusive evidence to support that belief.’

‘Yet you authorized the SAS ambush at the police station, killing eight IRA suspects.’

‘Not suspects, Mr Secretary. All of them were proven IRA activists, most with blood on their hands – so we had no doubts on that score. That being said, I should reiterate that we certainly knew that the two ASU team leaders – Jim Lynagh and Patrick Kelly – were responsible for the death of the UDR man. So the SAS ambush was not only retaliation for that, but also our way of humiliating the IRA and cancelling out the propaganda victory they had achieved with the assassination of the Lord Chief Justice and his wife. Which is why, even knowing that they were planning to attack the Loughgall RUC station, we decided to let it run and use the attack as our excuse for neutralizing them with the aid of the SAS and the RUC. Thus Operation Judy was put into motion.’