Полная версия

Mountains and Moorlands

Collins New Naturalist Library

II

Mountains and Moorlands

W. H Pearsall

EDITORS:

MARGARET DAVIES C.B.E., M.A., Ph.D.

JOHN GILMOUR M.A., V.M.H.

KENNETH MELLANBY C.B.E.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR:

ERIC HOSKING F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

EDITORS

EDITORS’ PREFACE

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 2 STRUCTURE

CHAPTER 3 CLIMATE

CHAPTER 4 SOILS

CHAPTER 5 MOUNTAIN VEGETATION

CHAPTER 6 THE LOWER GRASSLANDS

CHAPTER 7 WOODLANDS

CHAPTER 8 MOORLANDS AND BOGS

CHAPTER 9 VEGETATION AND HABITAT

CHAPTER 10 ECOLOGICAL HISTORY

CHAPTER 11 UPLAND ANIMALS—THE INVERTEBRATES

CHAPTER 12 THE LARGER MAMMALS AND BIRDS

CHAPTER 13 ANIMAL COMMUNITIES AND THEIR HISTORY

CHAPTER 14 THE FUTURE—CONSERVATION AND UTILISATION

CHAPTER 15 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GLOSSARY

INDEX

Plates

Copyright

About the Publisher

EDITORS’ PREFACE

THERE are really two Britains—two different countries, their boundary a line that strikes diagonally across England from Yorkshire to Devon. To the north and west of this line is the region of mountains and old rocks; to its south and east the newer, fertile land of the plains. These regions differ vastly in their climate, rocks, soils, scenery, plants, animals—and men.

It is of the mountains and moorlands that W. H. Pearsall writes. Moorland, mountain-top and upland grazing occupy over a third of the total living-space of the British Isles, and, of all kinds of land, have suffered least interference by man. Mountains and moorlands provide the widest scope for studying natural wild life on land.

In the present volume Professor Pearsall has brought together the results of over thirty years’ work among the high hills, the lakes and the moorlands of northern and western Britain. He is a botanist, but these pages show that animals have appealed to him almost as much as plants, a double interest that is rarer than it should be among naturalists. It is doubtful whether any other author could, single-handed, have presented such a well-balanced picture of the wild life of an area as Professor Pearsall has done in this volume.

Although he is now banished to the gently undulating south (he is head of the Botany Department at University College, London) the whole of Professor Pearsall’s previous working life has been spent within call of the mountains and moorlands about which he writes—at Manchester, at Leeds, and finally as Professor of Botany at Sheffield University. During this period he has made many outstanding contributions to ecological research, especially in the Lake District, but it is obvious from his book that the severely scientific discipline that these researches demand has by no means extinguished his deep love of the countryside in which they were carried out. On the contrary, the aesthetic and the scientific approaches have reinforced each other, as they should—but frequently do not—in any fully developed naturalist.

For many people, perhaps the most arresting point in the book will be the idea that since the end of the Ice Age our mountains and moorlands have been subject to a process of inevitable change, one of the trends being towards the growth of bog and peat-moss at the expense of grassland and woodland, and towards a general impoverishment of soils; further, that during the last 3,000 years or so this and other changes have been progressively accentuated by man’s interference, so that the difference between the natural history of our moorlands to-day and a bare two centuries ago is very marked. Indeed, work such as Professor Pearsall’s is putting the history of our country in a new light. His chapter on the future possibilities of our uplands is equally striking.

Before the growth of modern transport most people in the south of England had little chance of knowing how those in the rest of Britain lived; there was little opportunity for studying and appreciating the lives of those who lived in the unspoilt countryside of the north and west. But to-day the mountains and moorlands of Highland Britain are within reach of every one, and we hope that Professor Pearsall’s book will help to quicken—and guide—interest in those parts of this country which now provide the main (almost the only remaining) opportunity for observing and investigating wild life and human problems in Britain as it was before modern man’s heavy hand was laid upon it.

THE EDITORS

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

THIS book is an expression of many happy days in the field and is thus a tribute to the many naturalist friends who have consciously or unconsciously helped towards it by sharing their interests and enthusiasms. I should like to think that they may find some satisfaction in its dedication and that they would feel that they had in part contributed towards its creation.

When so much is owed to others, it may seem invidious to mention any by name. But the largest part of the animal population is composed of insects and for these specialised knowledge is unavoidable, even for a general review. I count myself extremely fortunate in having been able to obtain the sort of information I wanted, and also pertinent criticisms, from Mr. C. A. Cheetham, Professor J. W. Heslop Harrison and Mr. W. D. Hincks, the last of whom also verified the names according to the Check List of British Insects. Mr. W. H. R. Tams very kindly gave much help in the preparation of Plate 30. The Editors too have been generous in help and criticism; and, finally, a tribute must be made to the photographic skill of Mr. John Markham.

In spite of this, I fear that this may be thought an odd book, remarkable more for its omissions than its scope. It tries to integrate certain aspects of upland biology of which it may safely be said that about ten years’ intensive work would be required to do them reasonably well. The real integration, perhaps, is that it tells about some of the things that have interested its author.

W. H. P.

University College, London

PREFACE TO REVISED EDITION

Professor Pearsall died in October 1964. A lifetime of active work as a field ecologist, university teacher and administrator, ecological advisor and one of those most concerned with the foundation of the Nature Conservancy, had left him too little time to write. Mountains and Moorlands remains as his major work for the general reader; it is a classic, and must not be touched by a lesser hand. But in the twenty years since its publication, further research has inevitably modified certain concepts. When I was asked by Collins to revise Mountains and Moorlands for this edition, it seemed to me that Chapter 10, on ecological history, should be largely rewritten in the light of new work and the emergence of the technique of radiocarbon dating since 1950. Chapter 10 was partly based on the work of Dr. Verona Conway and myself, and the revised edition of this chapter has been approved by Dr. Conway and by Mrs. Pearsall. I am grateful to Miss Clare Fell for advice on changes in the interpretation of the archaeological record in North-west England since R. G. Collingwood’s account of 1933, which formed the basis of Professor Pearsall’s discussion of the ecological history of North-west England. In other chapters I have changed only a few sentences, to conform with new discoveries, and have provided additional bibliography to cover relevant work published since 1950. Chapter 15, a brief account of the work of the Nature Conservancy in Highland Britain, has been added to the book because of Professor Pearsall’s concern with the Nature Conservancy—he was for many years Chairman of its Scientific Policy Committee—and because of the relevancy of the work of the Conservancy to the matters discussed in Chapter 14 of Mountains and Moorlands, which was written before that work had begun.

The nomenclature of plants has been revised to conform with current usage; on the advice of various colleagues, the revised nomenclature, with two exceptions, conforms with that found in Clapham, Tutin and Warburg’s Excursion Flora of the British Isles, Second Edition; the Census Catalogue of British Mosses, by E. F. Warburg, Third Edition, published by the British Bryological Society in 1963; the Census Catalogue of British Hepatics, by J. A. Paton, Fourth Edition, published by the British Bryological Society in 1965; and A New Check-list of British Lichens, by P. W. James, in The Lichenologist, Volume 3, 1965. The exceptions are that Scirpus caespitosus has been retained, instead of Trichophorum caespitosum, as in Clapham, Tutin and Warburg, and that Cladonia sylvatica agg. has been retained, as it includes the two species, Cladonia arbuscula and C. impexa, of the Check-list.

W. P.

University of Leicester and The Freshwater Biological Association

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

“The grounde is baren for the moste part of wood and come, as forest grounde ful of lynge, mores and mosses with stony hilles.”

(LELAND)

A VISITOR to the British Isles usually disembarks in lowland England. He is charmed by its orderly arrangement and by its open landscapes, tamed and formed by man and mellowed by a thousand years of human history. There is another Britain, to many of us the better half, a land of mountains and moorlands and of sun and cloud, and it is with this upland Britain that these pages are concerned. It is equal in area to lowland Britain but its population is less than that of a single large town. It lies now, as always, beyond the margins of our industrial and urban civilisations, fading into the western mists and washed by northern seas, its needs forgotten and its possibilities almost unknown.

Nevertheless, to the biologist at least, highland Britain is of surpassing interest because in it there is shown the dependence of organism upon environment on a large scale. It includes a whole range of habitats with restricted and often much specialised faunas and floras. At times, these habitats approach the limits within which organic life is possible, and they are commonly so severe that man has avoided them. Thus we can not only study the factors affecting the distribution of plants and animals as a whole, but we can envisage something of the forces that have influenced human distribution. Moreover, in these marginal habitats we most often see man as a part of a biological system rather than as the lord of his surroundings.

This book, then, deals primarily with mountains and moorlands as habitats for living organisms. Many plants and animals are mentioned, usually without detailed descriptions, except where they can be seen to be a characteristic part of the environmental system as a whole, or where they illustrate typical relations between organisms and environment. For this reason also no attempt is made to give full lists. It is also inevitable that the plant-soil relationship occupies in outline a large part of the story because this is the feature which links the animate with the inanimate.

It would hardly be possible to frequent upland Britain without becoming an admirer of its beauty. Its scenery is due to the interplay of its geological structure, of its climate and vegetation, and of human influences. It thus becomes important to the biologist as an integration of the interplay of these habitat factors and often his first interest will be to look keenly at the scenery for clues in the analysis of the environmental factors. As Professor Dudley Stamp has pointed out in his volume Britain’s Structure and Scenery, the scenery of the British Isles is remarkable in its diversity, and this conclusion applies with special force to the British Highlands. Diversity of aspect means diversity of habitat and of biological pattern. It offers a fruitful and as yet hardly explored field for the naturalist’s work and one which is particularly attractive because very valuable results can be obtained without highly specialised knowledge or apparatus.

While the study of the relations between organism and environment is no new aspect of biological inquiry, it is nowadays dignified by a special name and is called the science of ecology. The ecological study of mountains and moorlands may be in its infancy but their fauna and flora have long been objects of interest to naturalists. It is evident from the routes they followed and the lists of plants they collected from 1660 onwards, that John Ray and his associates were no strangers to the high northern hills, but the first record of an ascent of a British mountain we owe to another botanist—stout Thomas Johnson—whose account of the ascent of Snowdon in 1639 all naturalists will enjoy, especially perhaps the concluding sentence: “Leaving our horses and outer garments, we began to climb the mountain. The ascent at first is difficult, but after a bit a broad open space is found, but equally sloping, great precipices on the left, and a difficult climb on the right. Having climbed three miles, we at last gained the highest ridge of the mountain, which was shrouded in thick cloud. Here the way was very narrow, and climbers are horror-stricken by the rough, rocky precipices on either hand and the Stygian marshes, both on this side and that. We sat down in the midst of the clouds, and first of all we arranged in order the plants we had, at our peril, collected among the rocks and precipices, and then we ate the food we had brought with us.”

Johnson lived in troubled times and he was later to die of his wounds as a Cavalier soldier. If interest in the Alps may be said to have started as a result of de Saussure’s scientific expedition to Mont Blanc in 1787, we may perhaps fairly regard Johnson as a British de Saussure at a far earlier date, though on a more modest and unassuming scale.

FIG. 1.—Map of areas discussed, showing some of the Nature Reserves in Highland Britain.

CHAPTER 2

STRUCTURE

THE British Highlands are composed of blocks of hard and old rocks that occupy the north and west of these islands. While the biologist is not primarily concerned with the manner in which these rocks originated and attained their present condition, the geological structure of the uplands is a matter of some importance to him because it determines the character of the soil and the nature of the habitats available for living organisms. Consequently, a slight acquaintance with geological structure and processes forms part of the necessary background of the present subject and one, moreover, which is of interest in helping us to understand the great scenic and biological diversity of different parts of Highland Britain.

Almost every mountain observer has been struck by the evidence of decay which centres around the larger peaks. There is shattered rock round their summits (see Pl. III) while below every crag we find scree and from every gully there runs a stone-shoot (see Pl. 2b) formed from débris coming down from above. In the mornings the ceaseless downward trickle of stones or the occasional rock-fall proclaims the constant attrition to which the steeper hills are subject. Thus to the distant observer the mountains may seem to be permanent, “the immortal hills,” but to those who know and move among them a different impression is formed, in which breakdown and change play by far the most prominent part.

The causes of this constant weathering of the rock surfaces are primarily the uneven contractions and expansions of the rocks caused by fluctuations of temperature, the action of rain and frost and the force of gravity. Any cracks that develop become filled with water and are expanded when the water freezes and widened when it thaws. The actions of rain and of gravity tend to remove the smaller rock fragments so that nothing accumulates to protect the constantly exposed surface. Thus the surface continues to be weathered away until the slope approaches an angle of rest (usually between 30° and 40°). Rainwash, soil-creep and the gradual downward movement of larger stones continue, long after this angle is reached, to move the materials towards the valley.

Still more important in the long run are the effects of running water, for this not only tends to move materials downwards, but it may also remove them from the area altogether. In the course of time, therefore, every mountain torrent erodes a gully of its own construction, and the coarser materials eroded are deposited below the gully on a gravel fan or delta (see Pl. 2a) while the finer materials are carried ultimately to the plains beyond the mountain area. It follows that the land-forms in the uplands tend to be those which have survived the processes of weathering and erosion. In terms of these ideas, the uplands, whether moorland or mountain, have survived because the rocks of which they are formed are harder or have resisted removal rather than because they are being or have been lifted up. At the same time there must have been some original mountain-building process.

Many facts can be used to illustrate this argument. Almost every visitor to the English Lake District becomes familiar with a type of scenery in which there is a foreground of lower and rounded hills, backed by a skyline of larger and steeper mountains. This is well shown in the photograph of Esthwaite Water in Pl. 3b and this type of scenery has a simple explanation. The rounded hills in the foreground are composed of rocks less resistant to weathering and the high mountains of harder or more resistant rocks, in this case the hard volcanic “tuffs” or ashy beds of the Borrowdale Volcanic series which make up much of the mountain core of the Lake District. Both to the north and the south of these hard rocks lie softer slates and grits. Although to the uninitiated these rocks present a generally similar appearance, they exhibit considerable difference in hardness. As the harder Borrowdale rocks have weathered much more slowly, they now generally form much higher ground than do the adjacent softer rocks. The actual junction of the harder and softer rocks is shown in Pl. I where it will be seen that the harder rocks are mountain slopes, the softer being soil-covered and cultivated.

There are many equally good examples elsewhere of the influence of the hardness or softness of rocks upon land forms. A second illustration may be taken from Scotland, where, north of the Highland line, there are to be found long stretches of steeply inclined and metamorphosed grits, hard and resistant rocks which give the line of the summits, Ben Lomond, Ben Ledi, and Ben Vorlich. The valleys intersecting this area lie on beds of softer rocks, shales, limestones and phyllites, which have suffered correspondingly greater erosion and so have been cut down below the general upland level.

The general concept of mountain structure thus illustrated can be applied on a larger scale, for it has been pointed out already that the distribution of mountains and moorlands in Britain is essentially that of the older and harder rocks. These lie, as we have seen, to the northwest of the British Isles, and their range covers all the main mountain areas. The causes of this distribution lie in the far-distant past when large-scale earth movements were taking place, and there seems to have remained since a tendency for the north and west of the British Isles to stand as a raised system. While any attempt to trace these mountain building movements lies outside the scope of the present discussion, it may be interesting to indicate something of their effects on upland structure.

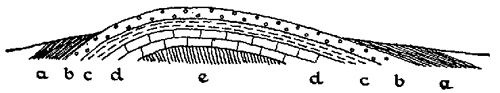

In the simplest cases, of which the Pennine range in Northern England is a good example, the upland area represents essentially a fold in the earth’s crust. In the Pennines, this fold runs approximately north and south and a transverse section through it would show the general arrangement represented in Fig. 2, with the newer rocks (including the Coal Measures) represented on either side of the fold, that is in Lancashire and Yorkshire, but absent from the top of the Pennines themselves. There is evidence of various types which points strongly to the probability that newer rocks, from the Coal Measures upwards, have in fact been removed by erosion from along the crest.

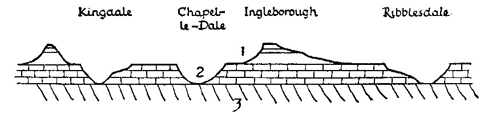

Thus the Craven Uplands, including Ingleborough at their southern end, are separated from the main block of the Southern Pennines by the great Craven Fault system. Just south of this fault, at Ingleton, coal was formerly mined from strata lying above those which correspond to the rocks on the top of Ingleborough. The assumption seems clear, therefore, that these Coal Measures have been removed by erosion from the area north of the Craven Fault.

The Craven Uplands are also interesting in another respect.

FIG. 1.—General character of Pennine anticline. (Diagrammatic.) a, Coal Measures; b, Millstone Grit; c, Yoredale Shales, etc.; d, Carboniferous limestone; e, Ordovician and Silurian.

FIG. 2.—Dissection of Craven Pennines by river valleys: 1, Yoredale rocks; 2, Carboniferous limestone; 3, Ordovician and Silurian. (Diagrammatic.)

The three parallel summits of the mid-Pennines, from east to west—Great Whernside (2310 ft.), Penyghent (2273 ft.) and Ingleborough (2373 ft.), but also, to the north-west, Whernside (2414 ft.) and Grey Gareth (2250 ft.), reproduce almost identical characteristics in structure and altitude. They are separated by a series of river valleys, Wharfdale, Littondale and Ribblesdale, then also by Chapel-le-Dale and King-dale, which have very obviously been cut down through the original rock formations, here almost horizontal (see Fig. 2). A reconstruction of the mid-Pennines on an east-to-west section thus shows these mountains as the surviving elements of the Pennine fold, resting on a mass of the still older Silurian rocks, upon which also the rivers now run. North and south of these Craven Uplands, the Pennines have commonly the character of a high moorland plateau (see Fig. 28). It is only when these plateaux have been greatly dissected by erosion and by river action, that distinctive mountain peaks are frequent. This has happened not only in Craven but also at the southern extremity of the Pennine range where dissection has also split up the plateau into peaks such as Kinder Scout and Bleaklow.