Полная версия

Grass and Grassland

Grass shoots do not, however, remain indefinitely in this vegetative stage; eventually they change to the flowering condition. When this occurs the stem apex ceases to produce new leaves and instead forms a rudimentary inflorescence. Once this change has taken place in a shoot, it produces no more new leaves and no more axillary shoots or tillers; the inflorescence develops, the stem elongates to bring it up above the level of the leaves, the flowers are pollinated, the fruit ripens and is shed, and the whole shoot dies. Growth of the plant is then continued by other tillers which are still in the vegetative state. The change from the vegetative stage to the flowering stage is usually a response to length of day; most British grasses are “long day plants” and so these changes take place in them as the days lengthen from spring to early summer.

The tiller must, however, have reached a certain size before it can respond to the increasing hours of daylight and this size varies in different grasses. If a small tiller can respond, then all the tillers will reach the necessary size during the year, before the days become too short again. In this case therefore all tillers will flower and die. Thus there will be no vegetative tillers left to continue growth and the plant behaves as an annual. If, however, the tiller cannot respond until it has reached a larger size, it will not flower until the late summer (aftermath flowering) or it may not flower that year. If, as is true of some grasses, a period of low temperature is necessary before response can take place, flowering will be delayed until the following spring. Meantime, the tiller, while still in the vegetative condition, will have produced further tillers so that the plant behaves as a long-lived perennial. Such plants produce some flowering shoots each year but always remain sufficiently vegetative to ensure continued growth.

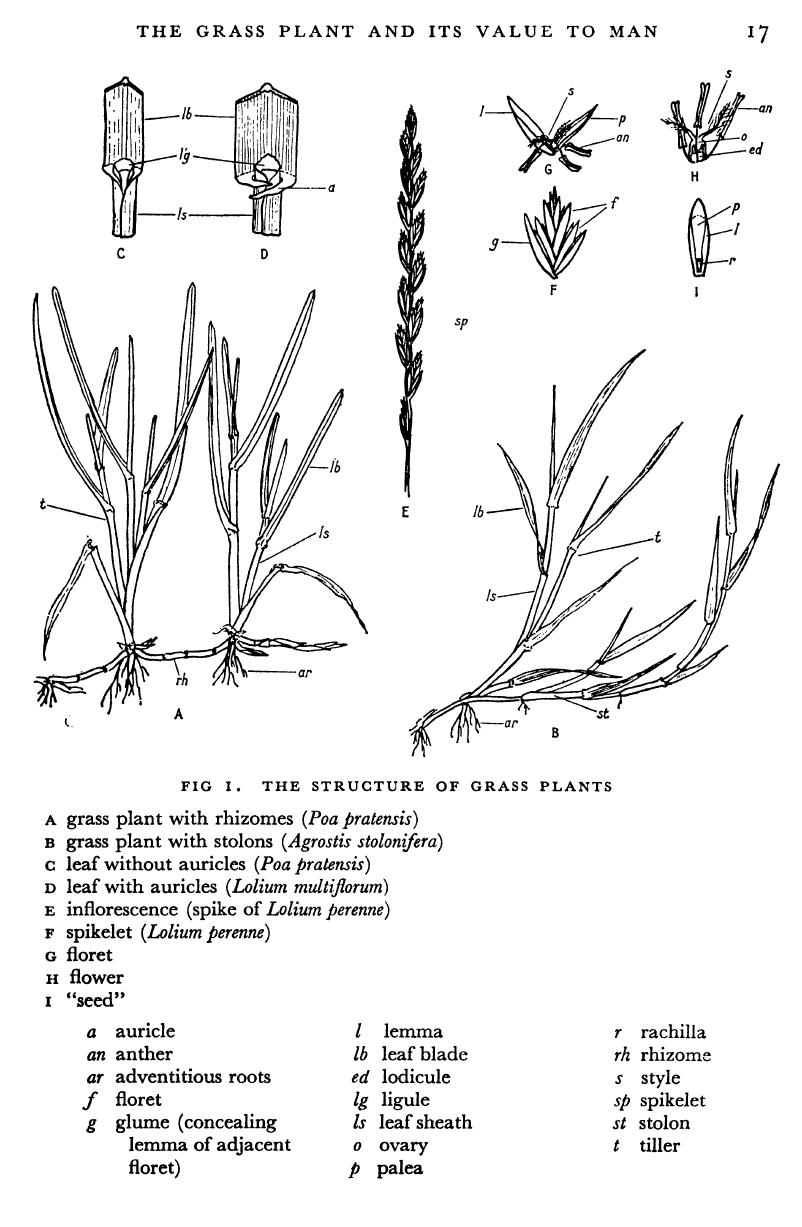

With few exceptions grasses have fibrous roots—in some species they are tough and cord-like—which arise adventitiously from the lowermost node or nodes of the stem. This capacity of grasses to produce numerous fibrous roots is of prime importance for it means that grasses, unlike plants with a main tap root, have great powers of recovery after injury. When the main tap root of such a plant is injured the plant probably dies; root injuries to grasses on the other hand may even stimulate new growth. Thus severe harrowing of an old pasture with heavy spiked harrows, which cut into the turf, tears out much of the matted growth, increases aeration, and brings about rejuvenation, with the result that the pasture “freshens up” with new growth. Similarly the groundsman, using “pruning” machines on the sports turf or lawn, encourages new, strong root and leaf development.

The roots of different species vary in length and are equipped with a very great number of root hairs. In some cases, like couch grass, underground, scaly, whitish or brownish creeping stems or rhizomes are formed and both roots and scale leaves are produced from the nodes of these rhizomes. In other cases, like creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera) and rough-stalked meadow-grass (Poa trivialis), thin, greenish or purplish, surface-creeping stems or stolons, like strawberry runners, are formed from the nodes, from which fibrous roots and green leaves are produced. Thus rhizomes and stolons are really modified stems, and grasses with such rooting, mat-forming systems cover the ground very rapidly in consequence. Such a characteristic is not always desirable and in some cases it presents serious problems. Any bud-bearing portion of a rhizome which is broken off from the root system can start a new and independent plant. Thus couch grass which can be a very serious weed on some types of arable land, becomes a menace by the very speed with which it reproduces itself. The small pieces of rhizome broken and dispersed in the course of cultivation give rise to new colonies of plants and it is not unknown for the growth of couch to be so great that the intended crop is smothered. Moreover, the diversion of food materials to the formation of such non-photosynthetic and inedible structures as stolons and rhizomes has the effect of reducing the maximum yield, and such grasses as bent and couch are, therefore, most unproductive. The highest yielding agricultural grasses, such as the ryegrasses, cocksfoot and timothy, are tufted, non-creeping species.

The flowering stems (“culms”) of the grasses are usually cylindrical and hollow except at the nodes or joints, where the stem is firm and solid and from where the leaves emanate. Culms vary not only in size, rigidity and number of nodes but may grow erect, prostrate or arise from a curved or prostrate base. The stems are usually smooth and highly polished. The leaves are parallel-veined and arranged in two rows alternating one with another on the stem. Each leaf is composed of a lower portion known as the “sheath” which may form a cylindrical tube enclosing the stem, or may be split, with the margins overlapping one another. Near the ground, the sheath may be coloured red, purple or brown which is constant for each species and constitutes an aid to identification. In some species, only the veins are coloured. The upper portion of each leaf is called the “blade”; this may be flat, rolled up and bristle-like, or folded about the mid-rib with the upper surface inwards, while the blades may be erect, drooping, or at right angles to the sheath. The blade, usually long and narrow with parallel sides or tapering to a pointed or blunt tip, often widens out at its base to form either a ledge or ear-like projections or teeth called “auricles,” which clasp the stem. Where the blade joins the sheath there is usually a membranous outgrowth, called the “ligule,” which may be pointed, blunt or ragged, long or short, or may be represented by a line of hairs. These characteristics afford still further means of identification. The leaves of some grasses are hairy, others free from hairs (glabrous); if present, the hairs may be most abundant on the sheath, on the upper or lower surfaces of the leaf blade or, in some instances, confined to the ribs or margins.

This key to the identification of the commoner pasture grasses by means of their vegetative characters has been compiled to enable the enthusiast when walking over a farm to distinguish the chief species making up the swards. It has been made as simple as possible and deals with only a few of the better known grasses. Readers who wish to identify a much wider range of species should consult Hubbard’s Grasses (1954).

KEY FOR IDENTIFICATION OF COMMON GRASSES WHEN NOT IN FLOWER

1 Leaf-blades more or less flat, breadth greaterthan thickness. 2 Leaf-blades bristle-like. 17 2 Shoot flat or oval, young leaves folded. 3 Shoot round, young leaves rolled. 7 3 Base of leaf-sheath coloured, blades ribbed onupper surface. 4 Base of leaf-sheath white, blades not ribbed. 5 4 Leaf-sheath red. Lolium perenne Leaf-sheath yellow. Cynosurus cristatus 5 Leaf-sheath thick, fleshy, blades broad, tapering. Dactylis glomerata Leaf-sheath thin. leaf-blades narrower. 6 6 Leaves tapering, pale-green, soft; plant perennialwith short creeping stems on surface. Poa trivialis Leaves parallel-sided, dark-green, stiff; plantperennial with underground creeping stems. Poa pratensis Leaves short; plant annual, tufted. Poa annua 7 Hooks (auricles) present at junction of leaf-bladeand sheath. 8 Auricles absent. 11 8 Base of leaf-sheath red; blades ribbed on uppersurface, shiny under surface. 9 Base of leaf-sheath white; blades dull, somewhathairy. White creeping stems below ground. Agropyron repens 9 Plant short-lived, old leaf-sheaths not persisting. Lolium multiflorum Plant perennial, old dead leaf-sheaths present atbase. 10 10 Plant small, smooth, auricles not fringed. Festuca pratensis Plant large, harsh, auricles fringed. Festuca arundinacea 11 Plant tufted or only slightly spreading. 12 Plant strongly creeping. Agrostis sp. 12 Leaves without hairs. 13 Leaves hairy. 14 13 Shoot base bulbous, pale, ligule short, pointed. Phleum pratense Shoot base not swollen, old sheaths dark brown, liguleblunt. Alopecurus pratensis 14 Sheath not split. Bromus mollis Sheath split. 15 15 Veins of sheath red. Holcus lanatus Veins of sheath not red. 16 16 Hairs scattered, blade very long, roots yellow. Arrhenatherum elatius Hairs on sheath pointing down. Trisetum flavescens Conspicuous tuft of hairs at top of sheath. Anthoxanthum odoratum 17 Sheath split; plant tufted. Festuca ovina Sheath not split; plant usually creeping. Festuca rubra spp. rubraThe inflorescence varies widely in the different genera and, if present, is the easiest means of identification. It is made up of a varying number of “partial” inflorescences called spikelets, each of which is composed of one or more flowers, each with two enveloping protective structures, the lemma and the palea. In most cases the grass flowers bear both stamens and pistil but in maize (Zea mays), for instance, the male flower is produced in the “tassel” and the female on the “cob” with its greatly thickened axis. Very rarely male and female flowers may be borne on different plants, as in buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides). The form of inflorescence is determined according to the way spikelets are arranged on the stem. The spikelets may be borne directly on the main axis to form a spike as in the ryegrass or couch grass; they may be borne on simple branches to give a raceme, as in false brome (Brachypodium spp.), or, as in the majority of grasses, borne on secondary, tertiary or even more sub-divided branches to give a panicle. The length and stoutness of the branches provide a wide variety of panicles between the extremes of an erect, close inflorescence, superficially resembling a spike, as in foxtail (Alopecurus spp.) or timothy, and one which is long and drooping, loose and spreading, like the bromes.

Flowering usually takes place from May to July, although in mild winters a number of species develop flower-heads in December or even January. Annual meadow grass, on the other hand, can generally be seen in bloom throughout the year. The first grass to flower in the spring is holy grass (Hierochloë odorata), which is in bloom about the end of March, but this species is very rare in the British Isles, and is confined to three Scottish counties and one Irish. Meadow foxtail (Alopecurus pratensis) and sweet vernal grass may flower in April, the ryegrasses in May, cocksfoot and the fescues in June, and timothy in July. Woodland and mountain species are somewhat later in flowering than species of the same genera growing in more open habitats or at lower altitudes. The early-flowering grasses are usually those in which only a comparatively short day is required for flower initiation; the later are those needing a longer day.

Since the actual flowers of grasses are very simple and show comparatively little variation, classification and identification have to depend largely on the structure and arrangement of the spikelets. Each true flower consists only of a single pistil with (usually) two styles, and (usually) three stamens, plus, in most grasses, a pair of minute scales which are known as “lodicules” and which have been regarded as representing very reduced sepals. Each flower is protected by two much larger structures, the inner, usually two-keeled, palea and the round, single-keeled, lemma. The lemma and palea fit closely together over the flower and are only separated for a short time when the lodicules swell up temporarily, pressing them apart, and allowing the styles and stamens to protrude and wind-pollination to take place.

Each true flower plus its lemma and palea is known as a “floret” and the spikelet consists of from one to about twenty florets. At its base there are two (occasionally one or none) protective structures, the glumes. Both the lemmas and the glumes may be furnished with bristles (awns), which are useful features for identification.

The following key will enable the more important species to be identified in the flowering stage.

KEY FOR IDENTIFICATION OF COMMON GRASSES WHEN IN FLOWER

1 Inflorescence a spike; spikelets not stalked. 2 Inflorescence a raceme. One very shortly-stalked,many-flowered spikelet at each node. Brachypodium spp. Inflorescence a panicle (spikelets on long or shortbranched stalks). 7 2 Spike branched. Spartina spp. Spike not branched. 3 3 One spikelet at each node. 4 Two spikelets at each node. Spike large, spikeletsseveral-flowered. Elymus arenarius Three spikelets at each node. Spikelets one-flowered, central one only fertile. Hordeum spp. 4 Spike one-sided; spikelets one-flowered. Nardus stricta Spike not one-sided; spikelets several-flowered. 5 5 Spikelet placed edgewise; 1 glume only. 6 Spikelet placed sideways on; 2 glumes. Agropyron repens (Wheat 3 or more large florets and broad glumes,lemmas usually awnless, and Rye with two large floretsand narrow glumes, lemmas always awned, come here) 6 Lemmas awnless. Lolium perenne Lemmas awned. Lolium multiflorum 7 Spikelets usually many-flowered (4 or more);glumes short, not hiding florets. 8 Spikelets few-flowered (2–5 usually); glumes long,concealing at least the lower florets. 19 Spikelets one-flowered; glumes long, concealingfloret. 23 8 Panicle branches mainly spreading. 9 Panicle branches very short, not spreading, so thatinflorescence looks more like spike. Sterileskeleton spikelets present as well as fertile. Cynosurus cristatus 9 Lemmas with awn on back. 10 Lemmas awnless or with awn on tip. 11 10 Lemmas rounded, spikelet oval. Bromus mollis & related species Lemmas keeled, spikelet triangular. Bromus sterilis & related species 11 Lemmas with rounded back. 12 Lemmas keeled on back. 16 12 Lemmas very blunt. 13 Lemmas bluntly or sharply pointed or shortlyawned. 14 13 Spikelets long, cylindrical. Glyceria fluitans Spikelets short, rounded-triangular. Briza media 14 Panicle purple, usually long and slender, stigmaand anthers dark purple. Molinia caerulea Panicle green, becoming brown or yellowish.Stigma and anthers pale. 15 15 Panicle and florets small. Festuca ovina & F. rubra Panicle and florets larger, two branches at mostnodes, with 1 or 2 spikelets on smaller branch,lemmas bluntly pointed. Festuea pratensis Panicle very large, 3 or more spikelets on smallerbranch, lemmas with awn-point. Festuca arundinacea 16 Lemmas straight, bluntly pointed. 17 Lemmas curved, with awn point, panicle largewith dense clumps of spikelets. Dactylis glomerata 17 Panicle small, no “web.” Poa annua Panicle larger, “web” of cottony hairs at base oflemma. 18 18 Spikelets rather small, panicle open, light andfeathery in appearance. Poa trivialis Spikelets slightly larger, panicle closer, denser andheavier in appearance. Poa pratensis 19 Panicle branches mainly spreading. Spikelet erect. 20 Panicle branches short, not spreading. Spikelet ofone shiny fertile floret and two sterile brownhairy awned lemmas. Anthoxanthum odoratum 20 Spikelets two-flowered, one fertile, one male only. 21 Spikelets with two or more fertile florets. 22 21 Spikelets fairly large, lower floret male withprominent bent awn, upper floret fertile. Arrhenatherum elatius Spikelets small, lower floret fertile, upper floretmale with small fish-hook awn. Holcus lanatus (Holcus mollis similar but with more prominent bent awn) 22 Panicle rather small, closing in fruit, yellow,spikelets 2–5 flowered. Trisetum flavescens (Helictotrichon spp. with larger spikelets would also come here) Panicle spreading, purplish-brown, branches wavy,spikelets small, two-flowered. Deschampsia flexuosa Panicle spreading, very large, often silvery, spikeletssmaller, two-flowered. Deschampsia caespitosa 23 Panicle somewhat spreading, spikelets very small. 24 Panicle always closed, densely cylindrical, spike-like. 25 Panicle large, cylindrical, tapering, spikelets verylarge, (on sand dunes). Ammophila arenaria 24 Panicle open in flower, closing in fruit. Agrostis stolonifera Panicle open throughout. Agrostis tenuis (Agrostis canina and A. gigantea would also come here) 25 Glumes stiffly-pointed, floret short, unawned,threshing out when ripe. Phleum pratense Glumes blunt, joined at base, floret awned andenclosed by glumes. 25 26 Panicle stout, spikelet oval, hairy. Alopecurus pratensis Panicle slender, spikelet oblong, not hairy. Alopecurus myosuroidesGrasses show an amazing tolerance to external conditions. For instance sheep’s fescue, which grows down to sea level in this country, has also been recorded on the highest mountains in Britain and at nearly 18,000 ft. in the Himalayas. Then again, many grasses from low-lying habitats in temperate regions adapt themselves to high altitudes in tropical countries. Others survive wide differences of climate, the classic example of adaptability being perhaps sweet vernal grass, which flourishes from sea level to above the snow line, is equally at home on sand, loam or clay, and is found in many countries of the world with vastly different climates, ranging from North Africa to Siberia.