Полная версия

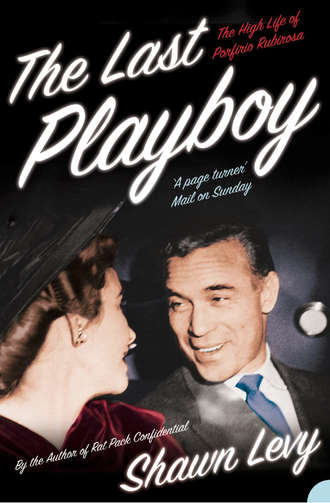

The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa

As a young soldier, he didn’t necessarily comport himself according to the strict standards of self-control that were so important to Trujillo. Having been promoted to first lieutenant and named a member of Trujillo’s personal staff, Porfirio was required to attend all of the deadly dull affairs of protocol of which the president was so enamored. Among these was a formal ball that would be attended by all of the civilian elite of Santo Domingo, a company by whom Porfirio was loathe to be seen in the role of aide-de-camp, a mere lackey. Ordered to attend in dress whites, he showed up instead in khakis, declaring that he hadn’t been told about the day’s dress code until it was too late and that his formal uniform was in the laundry. (“I still recall the look Trujillo gave me,” he would say more than thirty years later.)

With the other junior officers, Porfirio was ordered to stay put behind Trujillo, but he boldly strode over to where a young woman he knew was seated, and he took a chair beside her to chat. A nervous senior officer approached.

“Are you Lieutenant Rubirosa?”

“Yes.”

“The President has sent me to tell you that you may dance if you wish.”

The rest of Trujillo’s military corps gaped in astonishment as Porfirio enjoyed champagne and the company of the ladies for the rest of the evening. They had reckoned he’d be lambasted; instead, he had the time of his life.

That close call with the president’s anger wasn’t quite enough to scare Porfirio into the straight and narrow that was becoming the norm for trujillistos, as the most ardent followers of the president were known. In May 1932, he injured his knee in a one-car accident in San Pedro de Macorís, thirty miles east of Santo Domingo: As if he didn’t care how he’d comported himself he’d been speeding. “The distinguished young military gentleman,” as a fawning newspaper account referred to him, was attended in a local hospital and then transported by ambulance to the capital where he was seen by top military doctors. “The injury doesn’t apparently require additional care,” the report continued. “We are happy to wish him the quickest and most complete recovery.”

His first smash-up!

In July, Trujillo told Porfirio that his presence would be required the following day at the harbor, where a full complement of officers and a military band would greet the arrival of a ship that was returning the president’s daughter, Flor de Oro, from two years of school in France. Trujillo had special need for his audacious, French-speaking aide-de-camp at this particular reunion. “She knows Paris like you do,” he explained. And then, after a pause, he added, “Well, really, not like you do, I would hope.…”

The seventeen-year-old girl who got off that boat was, as she would later remember, “bedazzled” by her reception. “ ‘El Supremo,’” as she referred to her father, “stood there in an immaculate, starched white-linen suit, flanked by shining limousines and his handpicked aides. I noticed one lieutenant instantly—handsome in a Dominican uniform that had a special flair. Even the gold buttons looked real.”

It was, of course, Porfirio. And he, of course, noticed her noticing. “She was enchanting, with dreamy eyes and hair as black as night,” he later recollected in the florid style that overcame him when he wrote of romance.

No words were exchanged between the French-educated youngsters as Trujillo whisked away the daughter with whom he’d had virtually no contact since infancy. For Flor, riding with her father was quite nearly like making a new acquaintance. From the time the North Americans came to occupy the country, Trujillo had left his first wife and their daughter behind. “We knew little of what he did,” Flor remembered. “Three or four times a year, he’d come home, each time more and more overbearing. My proud job was to wash his military belt in the river for 25 US cents.”

Aside from such childish domestic chores, the girl served another purpose for her father: Trujillo spent Flor’s childhood offering different military or political bigwigs the chance to serve as his daughter’s godfather, a singular honor in a Latin family. But he never made the designation official, continually jockeying for a better and more prestigious candidate until the girl was almost fifteen years old and had either to be baptized or to be refused admittance to the French boarding school her father had chosen for her. (To get a sense of Trujillo’s relatively low standing at the time, the lucky winner of this sweepstakes was the family doctor; Flor, for her part, suffered the mortification of being the only baptismal candidate at that particular mass who walked on her own power to the altar rather than be carried as a babe in arms.)

When Trujillo failed to gain custody of the girl upon divorcing her mother, he moved them both to a small house in Santo Domingo and enrolled the adolescent Flor in a nearby boys’ military school. But she soon found herself among the students at the Collège Féminin de Bouffémont, a short distance from Paris.

It wasn’t necessarily a comfortable fit. “Naïve, thin, with legs long as a stork’s, unable to speak French, I was the shy tropical bumpkin,” she remembered, “the classmate of girls who included a princess of Iraq.” There were luxuries: her own thoroughbred horse to replace the burro she rode back home, summer in Biarritz, winter in St. Moritz, regular trips to Paris and the opera, the theater, the museums, and the shops. Still, she felt distant from her father; for most of her life, despite documentary evidence to the contrary, she claimed never to have heard a word from him in all her years away from home.*

Having been transformed, in her own estimation, into “that exotic hybrid, a French-speaking Dominican young lady,” she returned home not sure which father she would be meeting: the one who might hand her a $100 bill and declare “buy some toys” or the one whose volcanic temper aides warned her of in advance of their meetings. “Like the humblest dominicano,” she remembered, “I prospered and suffered under his rule and came to think of him as immortal. I had succumbed to the Dominican neurosis, a willingness to swallow anything because it came from Trujillo.”

The pomp of the greeting that summer morning at the port of Santo Domingo must therefore have reassured her, along with her father’s suggestion that she plan a coming-out party for herself, a major social event in a capital that had fallen increasingly under Trujillo’s sway in all its activities. Among those Flor hoped would attend but didn’t dare invite was that dashing lieutenant; years later she confessed, “It was love at first sight.” Eager to learn more about him, she quizzed her one Dominican friend, Lina Lovatón, a tomboy athlete who had been enrolled in the Santo Domingo military school with her. Lina knew little of Porfirio, and nothing further was learned at the party, during the whole of which the aide-de-camp stood stiffly behind the president, this time in proper uniform.

Soon Trujillo announced that the family and his personal staff would pass the rest of the summer at his estate in San José de las Matas in the western foothills of the Cibao. There, the attraction between the two young people escalated, though it would not always be clear in later years how exactly or at whose instigation. Flor would forever insist that they never spoke during this period, but Porfirio would recall idle conversations in French about Parisian landmarks and “the differences between the life one encountered in Europe and in the Caribbean.” That these initial contacts were, at any rate, fleeting they would both agree.

More was, however, suspected. The childless Doña Bienvenida, jealous of Trujillo’s attentions to this daughter of his first marriage, somehow got wind of the fledgling romance—Porfirio surmised that she overheard the two speaking French in the garden one evening—and warned her husband about the lieutenant’s impertinent behavior. Without a moment’s hesitation, Porfirio was reassigned to confined duty at the fortress in San Francisco de Macorís.

Again, what happened next would be in dispute: Either she wrote him to say that she was stricken at the thought of his departure, which assumes his story that they were already on close terms; or he wrote her, out of the blue, if her account of their merely polite relations is more accurate, to express his despair at being separated from her. (Years later, Rubi explained simply, “As in any good script, we found ways of getting letters to each other.”)

Whichever, the next step was indisputably hers. Learning that she would be attending a dance in her honor in Santiago—midway, more or less, between his new post and Trujillo’s ranch—she snuck off on horseback one afternoon and phoned the fortress to invite him. He accepted and, feigning a sore throat and the need to consult a specialist in the city, made his way to Santiago on the day of the dance.

She spied him first in the town plaza, fittingly enough having his boots blacked. Then at the dance, she was seated among the town’s elite when he walked confidently over and asked her to dance. Defying every principle of decorum, they danced together repeatedly—“five times in a row,” as she recalled—and compounded the sensation by speaking in French and then, during the open-air concert following the dance, walking slowly twice around the plaza, albeit under the vigilant eye of her chaperone.

As far as Porfirio was concerned, that was it: “From that moment I was in love, and Flor was as well.”

And that was it as far as Trujillo was concerned as well.

“The dance wasn’t even over when Trujillo heard,” Flor recalled. When she returned to San José de las Matas, she was met with a storm. Her father sent her directly to her room and began grilling his aides to find out who was responsible for the communications between Porfirio and his daughter and who was responsible for letting the banished lieutenant out of the fortress to attend a dance. Flor was terrified by the degree and intensity of his temper and cowered at the door listening as he sputtered to Doña Bienvenida, “She’s gotten herself mixed up with that good-for-nothing lieutenant!”

The next day, an even more dire fate awaited Porfirio: An officer marched into his quarters and announced that he was to be immediately expelled from the army and stripped of all his gear, including, to his special pain, “my uniforms, which I loved so well.”

This was a staggering blow, and he remembered it with high drama: “I was an outcast in my own country. Ignominiously dumped and rejected by the army. Marked on the forehead with the sign of infamy which no one could ignore.” He entertained the thought of exile but he couldn’t leave the island, he said in his most lugubrious voice, because “to leave would be to lose Flor. And to lose Flor would be to die. But to stay would also be to die.”

This was no exaggeration: Trujillo was entirely capable of having his onetime protégé eliminated and, in fact, he dispatched a team of hit men that very afternoon from his goon squad, who roamed the country in ominous red Packards doing the despot’s bidding.

Had he been stationed in any other city, Porfirio might not have survived the day. But San Francisco de Macorís was, of course, his birthplace, as well as the hereditary seat of both sides of his family. “My uncles and my grandfather united in counsel,” he recalled. “My uncle Oscar gave me a well-oiled pistol. A truck was obtained. It took me to a cocoa plantation owned by one of my uncles, Pancho Ariza, about 10 kilometers away.” For more than a week, he hid in an outbuilding on the farm, “staring into space, ruminating on this cascade of catastrophes.”

He was alone in neither his anguish nor his isolation. Before bolting to his hideout, he sent off a note to Flor describing his situation. The emissary who delivered it was tied by Trujillo to a tree and thrashed, while Flor watched in horror. She locked herself away from this frightening tyrant, refusing to speak with him, refusing meals, and writing letter after unsent letter to the young man who had suddenly come to dominate her dreams. Like the heroine of a pulp novel, she would love Porfirio to spite her father.

“Flor had the same strong blood in her veins as her father,” Porfirio would recall. “A will of iron and an indomitable courage guided her. She was the only one who could stand up to her father, even if he was in a state of fury.” When Trujillo sent an intermediary to speak with her, she replied, “Tell my father that I want to marry the man I love, and I will marry him. Otherwise I would not be worthy of being his daughter.”

At least that would be how Porfirio remembered it—or maybe how he imagined it. Flor’s memory was different: a cruelly imposed isolation; the ceaseless slander of the former lieutenant by her father and stepmother; a strange limbo, like being a nonperson.

In his hideaway, Porfirio grew impatient and decided, on instinct, that danger had passed. “It has always been one of my chief principles,” he later confessed. “I will risk everything to avoid being bored.” He rode back to his uncle’s home in town, shocking his family with his sudden appearance. “You don’t have a lick of common sense,” they admonished him.

But, in fact, the worst of it seemed to have passed. Indeed, the lull emboldened Doña Ana Rubirosa to visit Trujillo to plead for her son. As Porfirio recalled it, his mother stood up to the president by asking, “What secret mark is there against our family that Señor Trujillo cannot tolerate that a Rubirosa would dare put his eyes on his daughter?”

The meeting was barely a quarter hour along when Trujillo slapped his desk and declared, “That’s enough! They will marry right away!”

This was like tripping over a winning lottery ticket on the street. From disgrace and near-death, Porfirio was now slated to marry into the first family of the country. Maybe he was in love, truly, or maybe he was too scared to cross Trujillo a second time by refusing Flor, or maybe he was as bold a tíguere as the Benefactor himself. Whichever, he had heedlessly reached for the impossible by making eyes at the president’s daughter and, through charm, gall, and luck, had seized the prize. At twenty-three, he would be wealthier and closer to power than Don Pedro ever had been.

For Flor it was a stunning shock: “Five dances in a row, two circles around a park, an innocent flirtation, and I was to marry a man I scarcely knew!”

Still, marriage would liberate her, she hoped, from a man she knew all too well; as she admitted, she was “wild to leave my prison, to run like hell from Father, an instinct that was to propel me all my life.”

The nuptials were planned for early December at the fateful ranch house where the abortive courtship transpired. Trujillo orchestrated all the details: the invitations, the ceremony, the party. The best man would be the U.S. ambassador, H. F. Arthur Schoenfeld, whom the groom had likely never met. The ceremony would be performed by the archbishop of Santo Domingo. Flor was sent to the capital to have a dress made; her fiancé stayed with his family in San Francisco de Macorís—and was named, if only for the sake of having a title worthy of his entry into the president’s family, secretary to the Dominican legation in London.

On December 2, a caravan of trucks bearing flowers and bridesmaids wended from the capital to the wedding site. The groom was flown in on a military plane. The next day, after the civil and religious ceremonies in the town, the wedding party began late, at 4:30, on what turned out to be a rainy afternoon.

In the photographs of their wedding day, the newlyweds look frightened and tiny, despite their finery and the attendant pomp. Rubi stands with shoulders thrust back and tiny waist forward, a pompadour stiff on his head and a grin set in the baby fat of his cheeks. Flor is a head shorter, with wide-set eyes and a toothy smile; she holds a hand protectively across her breast, cradling her bouquet. They might be a prom couple on their first date.

As the photo attests, the wedding wasn’t a completely comfortable experience for the groom, who hadn’t once laid eyes on his prospective father-in-law since before being sent away for flirting with Flor. “During the ceremony,” he recalled, “I saw Trujillo again for the first time. Instead of his happy air, he was cold and quiet.” Nor was the bride entirely at ease, recalling that “Father hadn’t spoken to me since my engagement.”

But it was a lavish celebration nonetheless, with music, champagne, food, dignitaries, and a trove of gifts, which the bride said “would have filled a house.” (Conspicuously absent was the bride’s mother, still shunned by Trujillo as if dead.) By 7 P.M., the newlyweds were headed to Santo Domingo in one of their presents from the Benefactor, a cream-colored, chauffeur-driven Packard with their initials embossed in real gold on the doors.

Two days later, the capital’s most prestigious newspaper, Listín Diario, carried an account of the wedding written by someone whom the editors referred to as “an esteemed and distinguished friend of ours.” The author was, in fact, Trujillo, who would employ this and other newspapers throughout the tenure of his reign to carry, pseudonymously, compositions of his own, often using them to undermine or frankly smear someone who had fallen out of his favor. He could be vicious and snide in his writings, but this time, his tone was florid and precious:

Distinguished personalities of the country added to the glow of the nuptial ceremony … beneath the cool pines of the marvelous setting of San José de las Matas, an ambiance rich in exquisiteness.… The bride, who is a flower because of her perfumed name and because of the charms that flower within her, lit up a precious wedding dress.… It was one of the most aristocratic weddings ever recorded in the social annals of the Republic. The genteel couple have united their pulsing hearts in emotion. They have our most sincere and cordial wishes for their personal journey and their eternal happiness.

According to the report, the couple would live in “a handsome chalet within the bounds of the presidential mansion in the aristocratic and comely ‘faubourg’ of Gascue” in Santo Domingo—another gift from Trujillo.

But it was to a temporary home they retired that evening, their first as husband and wife and another experience that they would remember differently.

“When we left for our honeymoon,” Porfirio remembered, “I felt like the happiest of all men.”

Flor, on the other hand, was a nervous wreck. However much she had talked with her mother, her stepmother, or her older friends, she was entirely unprepared for the night’s activities. She wore a pink negligee into the bedroom and was startled into apoplexy by the sight of her husband’s erection. “I ran all around the house, and Porfirio chased me,” she remembered.

Somehow she talked him out of consummating the marriage that night, but she couldn’t keep him at bay forever. She let him have his way, however awfully. “I didn’t like it because I bled so much, and my clothes were ruined,” she confessed. “In time, he began to make love to me in different ways, but when it was over my insides hurt a lot. He was such a handsome boy and so charming that I let him do whatever he wanted. But he took so long to ejaculate that by the end I was a little bored.”

Et voilà the maiden marital bed of a man who would become famous as one of the great lovers of his time.

* A legend would evolve that the two men met after Porfirio had captained the Dominican national polo team to a victory over Nicaragua, but Porfirio’s equestrian life only truly began after he met Trujillo, and polo wasn’t played in the Dominican Republic, certainly not at the international level, until the 1940s, when he was himself instrumental in introducing it.

* Among the surviving correspondence was a letter from Flor de Oro at Bouffémont dated October 29, 1931, in which she thanked her father for his recent telegram and declared that she was looking forward to the fulfillment of his promise to bring her home for the coming summer. He responded three weeks later with a thoughtful and tender note in which he praised her maturation and indicated that he’d heard good things about her academic progress from the headmistress of her school.

FOUR

A DREDGE AND A BOTCH AND A BUST-UP

It was, by all objective standards, easy street.

In a house facing the sea in Ciudad Trujillo, the newlyweds lived in true splendor. Both had multiple servants; in addition to a valet and a masseuse, Porfirio employed a sparring partner—Kid GoGo, from back in his San Lázaro boxing promotion days—with whom he exercised daily in a ring he’d had erected in a spare room.

But the shadow of Trujillo obscured their horizon, and they were unable ever to forget the source of their good fortune. Flor recalled that their presence was required every day for lunch in the presidential mansion—“plain fare, rice and beans, no drinks, no cigarettes, no small talk: it was a bit like two slaves dining with the master.”

Along with all the gifts, Porfirio was given real work to do. Having decided against dispatching the couple to London, Trujillo appointed his son-in-law undersecretary to the president in April 1933, and then, the following July, undersecretary of foreign relations. In that post, Porfirio took charge of some genuinely sensitive responsibilities, such as communicating with Gerardo Machado y Morales, the Cuban president who’d been exiled to the United States after a coup in August; several rounds of correspondence between the two, with Porfirio gently dissuading the elder man from attempting to enlist Trujillo’s help in regaining his position, would survive. When foreign dignitaries came to the capital, Flor and Porfirio, the stylish, French-speaking face of the modern Dominican Republic, were trotted out to meet the visitors. A Haitian newspaper columnist was so charmed that he praised them as the “best-dressed, best-educated, most popular couple in town”; Trujillo, cross at having failed to be mentioned himself in a similar light, found in these compliments a slight, which he avenged by adopting a calculated iciness toward the couple.

There was phony work as well. In May 1933, Porfirio, who had never taken a course in business and had never had a bank account in his own name, was named president of the Compañía de Seguros San Rafael, an insurance firm established by Trujillo—like the other leading companies in virtually every field of Dominican commerce—as a false front for his private monopolization of the nation’s economy. The entire Trujillo family—the president’s many brothers and sisters, countless nieces and nephews and cousins—would be enriched through the years via such schemes. And not only blood relatives but in-laws and the relations of in-laws; Flor said of Porfirio’s kin, who’d so scorned the sight of him in his uniform barely a year earlier, “His family didn’t much cotton to Trujillo, but after the wedding they suddenly got big positions in the government.”

A lot of Dominican men would have been satisfied with this routine: the sinecures, the luxurious home, the servants, the prestige, the $50,000 bank account (controlled by Trujillo and in Flor’s name, but still). Not Porfirio. He was living within easy walking distance of his old haunts, the bars and brothels and clubs where he’d idled before he joined the army. He settled into a double life, half the time an obedient son-in-law, half a notorious rake participating in marathon drinking-and-whoring bouts: parrandas. When news of this behavior filtered back home, as it inevitably would, there were dustups with Flor. At least once Porfirio went so far as to hit her; she ran off to the palace, interrupting a meeting to tell her father of her husband’s violence; summoned by Trujillo, Porfirio mollified him by declaring that he’d struck her for failing to respect him under his own roof, a provocation with which any true tíguere would sympathize.

Even as he forgave that trespass, Trujillo harbored little warmth for his son-in-law. “I think that at bottom he never forgave me for marrying his daughter,” Porfirio surmised. “That his daughter could love someone other than him seemed impossible to him.” The president’s withering remoteness, coupled with Porfirio’s own restless inability to settle into the life of a bureaucrat, impelled him to ask for reinstatement to the Army, where he’d so enjoyed the life of vigor and male camaraderie. Trujillo consented, posting him at the rank of captain, assigning him no specific duties, and doing little to couch his disgust at Porfirio’s apparent contentment with his new station.