Полная версия

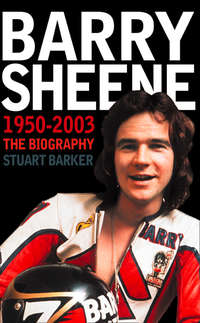

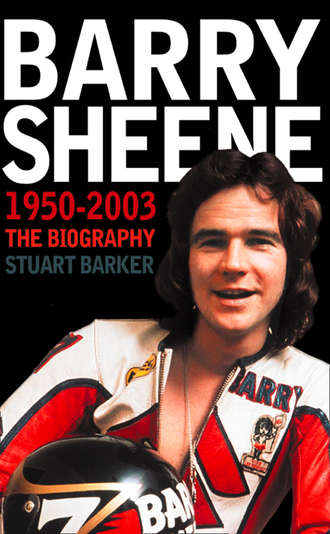

Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography

As things turned out, the day’s testing went so smoothly that Frank asked Barry to do some further bedding-in the following week. By that point the bikes had some miles under their belts and Barry was able to pick up the revs and push a good bit harder. He was also much more familiar with the track layout, the correct lines to take and the whole race-track environment, all of which is very alien to beginners. Being let loose on a circuit where there’s no cars, trucks or buses coming the other way, no speed limits, no mirrors on your bike and no restrictions or guides as to where you should position yourself on the road takes a bit of getting used to, even if you are Barry Sheene. But by the second weekend of testing, Barry was looking like he’d been born to it, and the fact didn’t go unnoticed. Reports from trackside marshals started to filter back to Frank that his son was looking a bit handy out there on the Bultacos; in fact, he looked faster than many racers those same marshals had seen. Maybe Barry should try his hand at racing? Frank related the news to his son, and Barry admitted to letting the praise go to his head. He readily agreed that maybe the time was right to carry on the family racing tradition and get out on the track in anger for the first time.

It was March 1968 and Sheene was 17 years old when he lined up on the starting grid, his gangly figure dwarfing the little 125cc Bultaco, for his first ever race. By today’s standards that’s pretty old – Valentino Rossi, for example, was a world champion at the same age in 1997 – but back in the late sixties it was more in keeping with the norm. It was an impressive debut by anyone’s standards. Sheene had worked his way up to second place in the race and was threatening the leader Mike Lewis when it all went wrong: the Bultaco seized, as it had never done during the running-in period, and spat its rider off over the handlebars. It wasn’t Barry’s fault in any way, but his detractors have often sniggered over the fact that Sheene crashed in his very first race. Indeed, that first race established a pattern that was to become all too familiar for Barry Sheene: being on the edge of glory just moments before a fall.

James Wilson was having only the second outing of his racing career that day on a 204cc Elite-engined Ducati. He recalled, ‘I remember I went up the inside of Sheene at Druids on one lap then went down through Southbank, and then bang, my clutch went and Barry came flying past me. His Bultaco was very quick, but then he locked up as well and crashed, although it wasn’t a bad one. The van took us back to the paddock together and we nattered in the van quite a bit. There was none of this “I’m a hero” kind of stuff. I knew about Barry from the paddock; he was the guy with the long blond hair who was always having a laugh and smoking a fag. He looked like a bloody good rider even back then; he really stood out. I mean, I stood out as well, but I had no help at all while Barry had his mum and dad, his sister and a van filled with all the right stuff. He didn’t have loads of money but he had enough, and he had a wealth of experience because of his family background. I was envious, not jealous, of the help Barry had. I knew then that he was going somewhere because he could ride and he had the right back-up as well.’ Wilson also remembered Sheene drawing attention to himself in the paddock that day, one of the few times anyone can remember him being violent. ‘I remember he punched the lights out of somebody that day because they owed money to Franco. I don’t know if he ever got the money but I doubt if the guy ever went near Barry again.’

Money aside, Frank Sheene must have been wondering what he’d got his son into when he learned that Barry had banged his head quite badly, lost some skin off his hands and cut his lip. Protective racing gear in the late sixties was extremely primitive compared to modern helmets, leathers, gloves and boots; a rider would probably be completely unscathed if he had a similar crash today. As it was, Sheene displayed admirable courage by ignoring his injuries and any psychological effects of the crash, and by refusing to be carted off by the circuit ambulance to hospital for a check-up. Instead he lined up to take part in the 250cc race on his other Bultaco.

Frank hadn’t wanted Barry to go back out again, but, showing the guts and determination that would eventually make him famous, he went out and finished third in the first event he ever completed. In a way, that first race day was a microcosm of Sheene’s career. He rode well, crashed, ignored his injuries and came back to finish strongly, both defiant and jubilant. He proved right from the start that he wasn’t a quitter.

A rostrum position for his first-day’s racing was a great achievement, but an even better result wasn’t very far away. Just one week later, and again at Brands Hatch, Barry took his first race win, and he did it in style by an incredible 12 seconds. And the best was yet to come. Frank had a special 250 Bultaco he had bored out to a larger 280cc capacity, and he wanted to know how it would compare against the machines in the 350 race. As things turned out, the bike didn’t compare – it totally dominated. Beaming with pride, Frank watched his son, and his project bike, finish half a lap ahead of the rest of the field, Barry romping home to take his second victory of the day.

Sheene junior was ecstatic. He might have been shaking with excitement after his first race win, but second time round he was completely overjoyed. Having proved to any doubters that his first victory was no fluke, he suddenly found himself the centre of attention in the paddock as members of the press and fellow racers gathered round to congratulate him. Keener paddock observers realized that the gangly Londoner wearing a cheeky smile from ear to ear was a star in the making. Those who didn’t take notice soon would, because Barry Sheene had finally arrived and motorcycle racing would never be the same again.

CHAPTER 2 THE RACER: PART ONE

‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat.’

RON HASLAM

After scoring such a resounding double victory in only his second-ever race meeting, in April 1968 Barry Sheene surprised many people by opting out of racing for a few months. Still unconvinced that racing was the proper career path to follow, he decided to take in a second tour of Europe, this time spannering for a rider called Lewis Young. Young was riding Bultacos, which by now Barry knew inside out, and he wisely came to the conclusion that a season following the Grand Prix circus around Europe would teach him more about the motorcycle racing business than a few weekends spent hurtling round British circuits. It might have seemed at the time an odd move to make, but it proved to be a well-judged one. This time, Barry really laid the foundations for his future career by getting to know all the circuits, the travelling routines and the way of life in the paddock, as well as gaining countless contacts all of whom would play a part in his future. The experience was heady and intoxicating, and by the time he returned to England that autumn not only was he 10kg lighter after eating so sparsely and irregularly, he had also decided to race again. Having seen some of the lesser lights who were competing in the Grands Prix, Barry had become convinced that he could beat most of them.

The year 1969 was Barry Sheene’s first full season of racing, and for the job in hand he had three Bultacos (125, 250 and 350cc), all immaculately prepared by himself and Frank. His Ford Thames van wasn’t quite so immaculate but it was good enough for the job. By the end of it he was being celebrated as the best newcomer of the season, having finished second to and 16 points behind established British rider Chas Mortimer in the 125cc British Championship. ‘I seem to remember that I won the 125 British Championship quite early on that year,’ Mortimer recalled, ‘then I went on to do some Grands Prix while Barry finished off the championship.’

That season very nearly became Sheene’s first and last when his hero and friend Bill Ivy was killed during practice for the East German Grand Prix in July. Sheene was devastated and suffered a massive asthma attack upon hearing the news. He hadn’t had a relapse since leaving school, and he never had another again. He seriously considered packing in the racing game after Bill’s death, but eventually managed to come to terms with the tragedy, as all motorcycle racers must do; it had to be chalked down as an accident and life had to go on. Sheene persisted, and went on to become Bill’s natural successor in the paddocks of the world, the cheeky cockney rebel with a playboy lifestyle and a gift for flamboyancy. Ivy would have been proud of him.

It was his natural flamboyancy that led Sheene to design the most famous crash helmet in motorcycle racing history, and it grabbed lots of attention during the 1969 season. While most other riders wore very basic designs on their helmets, if any at all, Barry had Donald Duck emblazoned on the front of his in a bid to attract attention to himself. It worked, and as the design developed over the years it became the most recognizable in the sport. The completed item featured a black background with gold trimmings, the famous number seven on the sides (more of which later) and, for the first time ever in the sport, the rider’s name on the back. ‘It wasn’t intentional,’ Sheene explained. ‘My helmet had gone away to a chap I knew to be painted and it came back with my name emblazoned on the rear. That’s neat, I thought, and I know I turned many heads when I unveiled it for the first time.’ Over the next few decades it became almost compulsory for riders to have their names on the backs of their helmets, and Barry claimed he was the originator of the fashion.

And his fashion sense didn’t stop at helmet designs; he also helped instigate the long-overdue decline in the use of all-black leathers which had so tarnished the image of motorcycle racing. In the twenty-first century motorcycle racing is one of the most colourful sports on the calendar, but it wasn’t always the case, far from it in fact, and Sheene played a large part in the technicolour transformation. In 1972 he ordered a set of white leathers, again largely as a gimmick to get noticed but also as a way of improving the sport’s then drab, greasy image of rough men in black leathers riding noisy, smelly motorbikes. He wasn’t the first rider to brighten up the sport, however, and not everyone was blown away by his garb, as Chas Mortimer testified. ‘I don’t particularly remember Barry’s Donald Duck helmet and white leathers standing out in those days. I mean, I had white leathers then too. Rod Scivyer was the first person to wear them in about 1967 or 1968.’ Sheene would later ditch the white colour scheme believing it was a step too far, but he would go on to wear other brightly coloured leathers such as the famous blue and white Suzuki garments and the even more famous red and black Texaco outfit.

With the trauma of Bill Ivy’s death behind him, Sheene set about preparing for the 1970 season with a team set-up and determination as yet unseen. The icing on the cake was the purchase of an ex-factory 125cc Suzuki from retired rider Stuart Graham. It cost a whopping £2,000, which was an enormous sum at the time and certainly out of Barry’s reach without the help of his dad. Barry used every penny he had to secure the bike – he was still driving a lorry for up to 14 hours a day to raise funds – and borrowed the rest from Frank, though he insisted he paid every penny back.

He made a point of letting everyone know that he repaid his father because he had always been acutely aware of the perception that he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth when it came to racing. After all, he’d had two factory Bultacos for his first outing, a world-class tuner in his dad and, through his father’s connections, advice from some of the best riders in the world. Ron Haslam, who began to challenge Barry’s supremacy on the domestic scene in the mid-seventies, recalled Barry’s machinery advantage. ‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat. I was helping my brother [Terry Haslam, who was killed racing in 1974] who was beating him sometimes even though he didn’t have all the tackle Sheene had. Sheene had factory bikes from the start so it was such a big thing for my brother to beat him on lesser machinery.’ Ron himself struggled against Barry on ‘lesser machinery’ on many occasions; whenever he came out on top it was always sweetly satisfying. ‘Sheene was like any rider in that he thought he was the best, as I did. You have to think that. He had superior equipment but he was still beatable, and I always believed I could beat him.’

Barry knew that his little ten-speed Suzuki was fast enough to run at World Championship level, and that’s exactly where he intended to be for his third year of racing – a feat almost unheard of in the modern Grand Prix world. Having won his first race on the Suzuki at Mallory Park, Sheene became so dominant on it in Britain that year that he later left it at home and raced the Bultaco instead. It appeared to be an extremely sporting gesture but was, in essence, more of a shrewd financial move: the Suzuki was much too precious to risk in British rounds when it wasn’t needed, and Barry couldn’t afford to be faced with astronomical spares bills should he crash the bike or damage it in any way. The Suzuki was, however, the weapon of choice for the last Grand Prix of the season in Spain, which also happened to be Barry’s first. He had already wrapped up the 1970 125cc British Championship for his first-ever title and decided he needed to up the stakes as far as the competition went if he was to continue on his steep learning curve.

John Cooper remembered watching – sometimes from trackside, sometimes on the track – as the young Sheene progressed. ‘Initially Barry was like everyone else. He came up through the ranks in 125s and 250s, but he was always a good rider. At one point I had a 250cc Yamsel [a Yamaha engine in a Seeley frame] and he had a 250 and 350cc Yamaha so we often raced each other and he used to say to me, “I wish you’d bloody pack up and give me a chance.”’ Sheene didn’t get his chance until 1973 when Cooper retired after almost 20 years of racing. ‘Barry’s career just overlapped mine. When I finished racing he became really good. But he did ride my Yamsel a few times in the early seventies if I wasn’t using it just because it was a particularly good bike. He couldn’t beat me when I was on it really because his bikes were fairly standard at the time, but then he got the works Suzuki 500 and by then I had packed up and Barry just went from strength to strength.’

One week before that Spanish Grand Prix, Barry entered a big Spanish International event and actually managed to beat the current World Championship leader, the Spaniard Angel Nieto, to the great displeasure of the partisan crowd. It’s worth noting that big one-off international race meetings for bikes have now all but disappeared, but in the seventies there were many big-money meets which attracted all the best riders, and a win in one of those was equivalent to a Grand Prix win by virtue of the fact that all the GP competitors were entered in the race. They were also financially profitable, as Sheene explained in the 1975 Motor Cycle News annual. ‘At a Grand Prix, I could make between £200 and £500 for one start, but at a non-championship meeting in France, say, I could ask for over £2,000 – and get it.’ The risk of injury in non-world championship events eventually heralded their demise in the eighties; for sponsors, manufacturers, riders and teams, the World Championship had to come first and they actively discouraged their contracted riders from taking part in any other events.

Sheene’s Spanish win was just what he needed before making his Grand Prix debut, and only a small misjudgement in the setting up of his bike robbed him of the chance of winning that race too. He had been only half a second slower than Nieto in practice despite never having ridden the Montjuich Park circuit before, but his bike was slightly undergeared and Nieto won by eight seconds, with Barry a huge 40 seconds ahead of the third-placed rider Bo Jansson. It was a sensational debut, and also the start of a great friendship between Sheene and Nieto, who would play a big part in helping Barry learn Spanish. He later learned to speak Italian and French as well, to varying levels of fluency, allowing him both to read what was written about him in the bike press of those countries and to conduct interviews with their media – always a popularity booster when very few Brits bothered to learn a second language. Sheene’s Japanese was not as good, but it too proved invaluable over the years when dealing with his Japanese employers Suzuki and Yamaha and their respective mechanics.

Sheene also had his first ride in the premier 500cc class at the Spanish Grand Prix that weekend, although his debut cannot be taken too seriously. Up against the mighty 500cc MV Agustas, Barry pitched his little (albeit overbored) 280cc Bultaco just for a bit of fun. Even so, he managed to work his way into second place in the race before the Bultaco seized, putting an end to his efforts. Barry’s first ride on a real 500cc bike came at Snetterton that same year when he raced a crash-damaged Suzuki 500 his father had pieced back together. For once, though, Barry didn’t have superior machinery, and it showed as he failed to set the world on fire and eventually retired from the race, but it was a start, and it marked the first time he’d ridden the kind of bike that would make him world famous.

With 1970 delivering the 125cc British Championship, a third place in the 250cc British series and a podium finish in his first Grand Prix, it was decided that nothing less than a full-on assault on the World Championship would suffice in 1971. The amount of travel and mechanical preparation required for such an effort necessitated Barry quitting all his little odd-jobs. From that point on, for better or worse, he would have to survive on whatever start money he could negotiate and whatever prize money he could win. He would be racing for survival.

Motorcycle Grand Prix racing today is a world of glamour and big money: multi-million-pound transporters and hospitality suites, worldwide television coverage, hosts of glamour girls pouting and posing their way through the paddock, luxury motorhomes for the riders to relax in and even more luxurious pay cheques with which to buy them. But in 1971 it couldn’t have been more different, especially for a newcomer like the 20-year-old Barry Sheene. Sheene himself would later play a leading role in adding such glamour to international paddocks, but his first full season was, as for most racers, a rough and ready, hand-to-mouth experience. There were no first-class flights to the far-off rounds; instead, Sheene and his mechanic Don Mackay took turns to drive Sheene’s newly acquired Ford Transit around Europe. Luxury hotels and restaurants were still some way off too, so the van doubled up as accommodation and kitchen – at least it did when there was something to cook, which for most of the time there wasn’t. Don was paid a wage as and when Sheene won any prize money, and a meal in a restaurant was a rare treat if the team had done particularly well. Sheene might have been the source of some envy in UK paddocks when he turned up with ultra-competitive bikes, but when it came to Grand Prix racing he was no more privileged than any other privateer.

Money was so tight at times that desperate and innovative measures were called for just to keep the show on the road. Sheene recalled a time when he had to ‘borrow’ some red diesel from a cement mixer in West Germany so that he could make it to Austria. When he got there, he asked the race organizer to up his starting fee from £30 a race because he needed money for food for the coming weeks. When the organizer refused on the grounds that no one knew who Barry Sheene was, Sheene offered a unique solution: if he could qualify in the top three in each of his three classes, he would be paid £50 each time; if he couldn’t, he would be paid only £20. The organizer, thinking he could save some cash, agreed, but he’d seriously underestimated Barry’s talents. Sheene got his £150.

Financial hardship aside, the year went remarkably well, Barry scoring a third place on the 125cc Suzuki at the first Grand Prix in Austria. He was also on the pace in the 250 and 350cc classes, but mechanical gremlins robbed him of any more finishes, as they did in West Germany, too. A look at the results sheets of Sheene or any other rider from that era will show just how many mechanical breakdowns a rider typically suffered in a season. To a modern-day GP enthusiast this will seem inexcusable; after all, aren’t top Grand Prix mechanics paid handsomely to prevent just such occurrences? Breakdowns are now so rare as to be a real talking point among paddock pundits and the press, but in the seventies they were still commonplace. Reliability has improved massively in the three decades since Sheene first hit the Grand Prix trail, and the money now being thrown at teams allows them to replace parts much more regularly, further lessening the chances of any technological mishaps. While Sheene might have suffered an apparently high number of mechanical hiccups, other riders did so too, so it all balanced out over the course of a season. The old points system, where riders could drop an allocated number of their worst results, further helped to create an even playing field.

The potential dangers of mechanical problems increased considerably when the GP circus travelled to the unforgiving public-roads course that was the Isle of Man TT, Britain’s round of the World Championship at the time, and a place Sheene learned very quickly to hate. The TT had started in 1907, and Barry had enjoyed the meet as a young spectator and paddock helper. Riding it, though, was a different matter altogether. The course is unique in that it is 37.74 miles long and lined with walls, houses, lamp-posts and every other hazard you’d expect to find on normal rural and urban public roads. Grand Prix circuits in the seventies were still nowhere near as safe as they are now, but they were a lot safer than the TT course, if only because they were shorter and easier to learn. In 1971, Sheene decided to race on the Isle of Man to try to score some valuable points for his world title campaign. It was a move that would define Sheene’s views on the event and make him many enemies among traditionalists who continued to support the TT despite its perils.

Those traditionalists have always scoffed at the fact that Sheene crashed out of his first race there, but he’d actually been on the leaderboard before the incident. He posted the third fastest time in practice on his 125cc Suzuki and was leading the race at one point on the opening lap until he hit thick fog and eased off the throttle. When his overworked clutch bit too hard just after the start of the second lap, Sheene was tossed from his bike at the slow, first-gear Quarterbridge corner and his race was run – much to Barry’s relief, as he’d been hating every minute of it. But that wasn’t quite the end of Sheene’s TT career: he still had an outing in the production event on a 250cc Suzuki. Again, he posted respectable times in practice, but after suffering a massive tankslapper (or ‘speed wobble’, as it was more quaintly referred to at the time), during which the front end of the bike shakes viciously from side to side, parts of his machine started to work themselves loose and Barry pulled in after just one lap. He never raced on the Island again.

A rider’s decision not to race at the TT would never normally cause any kind of commotion; it is a free world after all, and no one forces racers to take part in the TT. But Sheene wasn’t content just to stay away from the island. Over the next few years he embarked upon a sustained one-man attack on the event and played a major role in the TT eventually being stripped of its World Championship status – a crime for which some have never forgiven him.

Racing fanatics fall into one of two camps over the whole Sheene/TT issue: if you love the TT, you hate Barry Sheene, and if you hate the TT, you tend to agree with Sheene’s actions. Barry’s major bone of contention was that riders shouldn’t be asked to race on such a dangerous track just to gain championship points. He never wanted the TT to be banned as such, he just wanted riders to have the choice of whether or not to race there, his thinking being that when valuable points are at stake riders may be tempted to push their luck to earn a few. TT supporters claimed that the throttle works both ways and riders can take things as easy as they want to, thereby reducing the dangers. Many supporters of the event have said that Barry was just too scared to race there, or that he couldn’t be bothered to spend the usual three years to learn the course well enough to win on it. The second argument falls down when you consider that Sheene was leading his first race there before he crashed, and Barry himself responded to the first accusation: ‘The Mountain [TT] circuit did not frighten me in any way. No circuit frightens me. I just couldn’t see the sense of riding around in the pissing rain completely on your own against a clock. It wasn’t racing to my mind.’