Полная версия

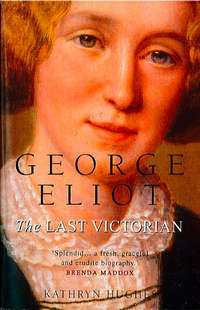

George Eliot: The Last Victorian

First Mr Sibree himself tried to convince Mary Ann of the literal truth of the Gospels in a series of encounters so intense that Mary Ann was left shaking.51 Next Mrs Sibree asked the Revd Francis Watts, a professor of theology from Birmingham, to try. Watts was a highly educated man with a formidable grounding in the German biblical criticism that had done so much to cast doubt on the divine authority of the Scriptures. But he too confessed himself beaten, murmuring only, ‘She has gone into the question.’52

Despite the fact that the most subtle and clever men in the Midlands could not persuade Mary Ann to change her mind, on 15 May 1842 Robert Evans was able to record the end of the holy war: ‘Went to Trinity Church. Mary Ann went with me to day.’53 On the surface it seemed as if Mary Ann had done the very thing she had declared she would not – compromised her convictions for the sake of social respectability. But it was, as she began to see for the first time in her life, more complicated than that. Agreeing to attend church while keeping her own counsel involved giving up the glamour and notoriety of the past few months. At the height of the holy war she had written a letter to Maria Lewis in which she spoke of her realisation that the martyr is motivated by the same egotistical impulse as the court sycophant.54 It was gradually dawning on her that her high-minded rebellion had been fuelled by her old enemy, Ambition.

A month or so later there was another suggestion, this time in a letter written to Mrs Pears from Griff, that Mary Ann no longer believed herself fully justified in the actions she had taken: ‘on a retrospection of the past month, I regret nothing so much as my own impetuosity both of feeling and judging’.55 It was a conclusion which was to stay with her for the rest of her life, for decades later she told John Cross that ‘although she did not think she had been to blame, few things had occasioned her more regret than this temporary collision with her father, which might, she thought, have been avoided by a little management’.56

It was not that she believed her commitment to seek God outside a formal structure was mistaken, simply that she began to realise that she had other obligations no less important. Her needs as an individual had to be balanced against her duties as a daughter. Ultimately, what sustained humanity was not adhering blindly to a theory, political belief or religious practice, but the ties of feeling which bound one imperfect person to another. She would not give up her new beliefs for the sake of respectability, but she would forgo the glamour of shouting them from the roof-tops. She would endure people thinking that she had fudged her integrity if it meant that she could stay with the beloved father whom she had so deeply hurt. Far from giving up the authority of private conscience, she was stripping it of all its worldly rewards, including the glamour of being thought a martyr.

Eighteen months later, in October 1843, Mary Ann wrote out her fullest statement on the matter in the form of a letter to Sara Hennell, Cara’s elder sister, who had since become her best friend. By now she had had time to absorb and reflect upon the turbulence and pain of the holy war. Her personal feelings of regret had been broadened into the kind of generalised observation on human nature which would come to typify the wise, tolerant narrative voice of her novels. ‘The first impulse of a young and ingenuous mind is to withhold the slightest sanction from all that contains even a mixture of supposed error. When the soul is just liberated from the wretched giant’s bed of dogmas on which it has been racked and stretched ever since it began to think there is a feeling of exultation and strong hope.’ This soul, continues Mary Ann, believes that its new state of spiritual awareness more than compensates for the old world of error and confusion left behind. What’s more, it is determined to spread the good news by proselytising to all and sundry. A year or two on, however, and the situation appears quite different. ‘Speculative truth begins to appear but a shadow of individual minds, agreement between intellects seems unattainable, and we turn to the truth of feeling as the only universal bond of union. We find that the intellectual errors which we once fancied were a mere incrustation have grown into the living body and that we cannot in the majority of causes, wrench them away without destroying vitality.’ Finally she broadens her argument, linking her own experience within the Evans family to a model of the world at large.

The results of non-conformity in a family are just an epitome of what happens on a larger scale in the world. An influential member chooses to omit an observance which in the minds of all the rest is associated with what is highest and most venerable. He cannot make his reasons intelligible, and so his conduct is regarded as a relaxation of the hold that moral ties had on him previously. The rest are infected with the disease they imagine in him; all the screws by which order was maintained are loosened, and in more than one case a person’s happiness may be ruined by the confusion of ideas which took the form of principles.57

The conclusions Mary Ann drew from the holy war prepared the way for her response to the difficult situation, fifteen years later, of being the unmarried ‘wife’ of George Henry Lewes. Living outside the law, she was socially ostracised in the same way Robert Evans feared would result from her non-attendance at church. However, much to the chagrin of her feminist friends, she refused to be known by her single name and insisted on being called ‘Mrs Lewes’. She steered clear of giving support to a whole cluster of causes, including female suffrage, which might be supposed to be dear to the heart of a woman who had shocked convention by living with a man outside wedlock. This fundamental separation of private conscience from public behaviour was the founding point of Eliot’s social conservatism. The fact that she loved a married man might authorise her own decision to live with him, but it could never justify a wider reorganisation of public morality. Family and community remained the best place for nurturing the individual moral self. Social change must come gradually and only after a thousand individuals had slightly widened their perceptions of how to live, bending the shape of public life to suit its new will. Revolution, liberation and upheaval were to have no place in Mary Ann’s moral world.

Nor did they have any in her fiction. George Eliot’s heroes and heroines may struggle against their small-minded communities, but in the course of their lives they learn that true heroism entails giving up the glory of conflict. Reconciliation with what previously seemed petty is the way that leads to moral growth. Romola, fleeing from her unfaithful husband Tito, is turned around in the road by Savonarola and sent back to achieve some kind of reconciliation. Maggie, too, returns to St Ogg’s after she has fled with Stephen and submits to the censure of the prurient townspeople. Dorothea’s fantasies of greatness end up in the low-key usefulness of becoming an MP’s wife.

The holy war cast a long spell not only over the fictions Mary Ann was to write, but over the intimate details of her daily life. None of her relationships would ever be quite the same again. On the surface, her friendship with Maria Lewis continued much as before. The first few letters of 1842 are lighter because more truthful. However, soon the correspondence starts to fail, spluttering on fitfully until Robert Evans’s death in 1849, but with a notable lack of candour on Mary Ann’s part. In a letter of 27 May she politely declares herself ‘anxious’ about whether Maria plans to visit, but prepares herself for the fact that Maria may be too ‘busy’ to reply immediately.58 What Mary Ann had perhaps not fully recognised was that Maria was lonely and reluctant to give up her friendship with a family which had so often provided her with a home during the holidays. In fact, Maria continued to visit Foleshill over the next few years, but there was an increasing sense that she was visiting the whole family (she had, after all, taught Chrissey too) and not just Mary Ann. And there are signs that Mary Ann found these visits an increasing chore. In a letter of 3 January 1847 Cara wrote to her sister Sara, ‘[Mary Ann] is going to have a stupid Miss Lewis visitor for a fortnight, which will keep her at home.’59 The nastiness of the tone is a surprise – Cara was a sweet-natured woman not inclined to hand out easy snubs. More than likely she was repeating what she had heard Mary Ann say of the squinting, pious, middle-aged schoolmistress who refused to realise that she was no longer wanted.

The exact end of the relationship is not clear. Reminiscing after Eliot’s death, her friend Sara Hennell recalled that the estrangement had been ‘gradual, incompatibility of opinions, etc, that Miss Lewis had been finding fault, governess fashion, with what was imprudent or unusual in Marian’s manners and that Marian always resented this’. Certainly Maria had made a sharp comment about the unsuitability of Mary Ann hanging on to Charles Bray’s arm ‘like lovers’.60 Still, it was Mary Ann who made the decisive break when she demanded that Maria return all the letters she had written her. Understandably hurt, Maria said that ‘she would lend them her, but must have them returned’.61 But once she had them in her possession Mary Ann reneged, citing the authority of a friend (probably Charles Bray) who told her that letters belonged to the writer to do with as she pleased. It is not entirely clear why Mary Ann wanted them. It may be that she felt the correspondence with Maria represented a part of her that had not so much been left behind as absorbed into a larger and more tolerant present. Gathering the letters may have been a way of recouping and qualifying the energy of the Evangelical years. Or perhaps Mary Ann still felt guilty about her less than straight dealing with Maria during the year running up to the holy war and wanted to regain control of the evidence of her hypocrisy. Or possibly she had simply outgrown this first important relationship with a person outside her family and wanted to mark its end. Significantly, she did not keep the letters but handed them over to Sara Hennell, the woman who had replaced Maria as her most intimate friend.

Mary Ann had no further contact with Maria Lewis until 1874, when she learned through Cara where she was living (in Leamington) and sent her a warm letter together with ten pounds – a practice she continued regularly until her death. Maria responded to the renewed contact with affection and admiration: ‘As “George Eliot” I have traced you as far as possible and with an interest which few could feel; not many knew you as intimately as I once did, though we have been necessarily separated for so long. My heart has ever yearned after you, and pleasant it is truly in the evening of life to find the old love still existing.’62

Maria was quite right about knowing Eliot better than anyone. After the author’s death she found herself eagerly courted by biographers keen for recollections of those early years. Although she was happy to talk to Edith Simcox when she came calling in 1885, she was understandably more cautious about giving away more tangible pieces of the past. Although on the best of terms with John Cross and delighted with his Life, still she refused to let him publish the letter which Eliot had sent with that first ten pounds. Having been robbed of the correspondence that had meant so much to her, she was determined to keep this tiny scrap of her star pupil to herself.

Mary Ann’s other friendship from those schoolgirl Evangelical years – with Martha Jackson – also did not survive the change in her religious beliefs. Martha’s mother, noting a change in the tone of Mary Ann’s letters and also hearing rumours of what had happened, ‘expressed a wish that the correspondence should close’, fearing that her daughter might be led into infidelity. In fact, there was little chance of that. Martha remained defiantly orthodox until the end of her life, refusing to let John Cross use extracts from her correspondence with Mary Ann on the strange grounds that, since he was probably not a Christian, he could not be trusted with the material.63

From the beginning of 1840 Mary Ann’s relationship with her Methodist aunt and uncle had also been cooling. As her Evangelicalism waned her letters to Derbyshire became sporadic and more inclined to talk about family matters – moving houses, marriages, births. A visit to Wirksworth in June 1840 had dragged, partly, she said later, because ‘I was simply less devoted to religious ideas’.64 A final extant letter to Samuel Evans, written by Mary Ann three months before her refusal to attend church, uses echoes of the old language of orthodox faith to hint at her new independence from it. ‘I am often, very often stumbling, but I have been encouraged to believe that the mode of action most acceptable to God, is not to sit still desponding, but to rise and pursue my way.’65

Her growing certainty of her own beliefs and her corresponding tolerance of other people’s meant that in the years that followed Mary Ann rediscovered her affection for her aunt and uncle. Mary Sibree recalled for John Cross how Mary Ann told her ‘of a visit from one of her uncles in Derbyshire, a Wesleyan, and how much she had enjoyed talking with him, finding she could enter into his feelings so much better than she had done in past times, when her views seemed more in accordance with his own’.66 Certainly by the time she came to write Adam Bede her antagonism towards orthodox ways of worship, particularly Methodism, had softened into an intuitive understanding of its value and meaning for people whose culture was now so very different from her own.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth and Samuel Evans never managed to extend that same understanding to their niece. Stories of her infamy became worked into the family inheritance. Their granddaughter remembered as a child being told by her mother that Mary Ann Evans was ‘an example of all that was wicked’. The Staffordshire branch of the family felt the same way. Well into the twentieth century, Mary Ann was still whispered about as a cousin ‘whose delinquency was an aggravated kind’.67

In the immediate aftermath of the holy war, Mary Ann had not yet developed the tolerance which would allow her to appreciate the value of views which were not her own. Nor did she have the social poise that would permit her to express that empathy gracefully. Thus it was awkward to discover on her return from Griff to Foleshill on 30 April 1841 that Elizabeth and Samuel Evans, together with William Evans, were making a visit. The next day was a Sunday and, keen to avoid conflict, Mary Ann took refuge at Rosehill, the Brays’ home. There, much to her delight, Cara let her look at the letters which her brother Charles Hennell had written to her while writing An Inquiry. At Rosehill, Mary Ann had found the spiritual and intellectual home that was to sustain her for the next eight years.

CHAPTER 4

‘I Fall Not In Love With Everyone’

The Rosehill Years 1841–9

FROM NOW ON Mary Ann spent every free moment with the Brays. Although Rosehill was less than a mile from Bird Grove, the contrast could hardly have been greater. While the Evans household was conservative, conventional and nominally devout, the Brays’ was radical, avant-garde and truth-seeking. Here was the perfect atmosphere for Mary Ann to explore her new beliefs and the emotional release that came with them.

At the time Mary Ann first went to Rosehill Charles Bray was at the height of his reforming zeal. Prosperous, young and boundlessly energetic, he pursued a bundle of good and forward-thinking causes in the city and beyond. A passionate advocate of non-sectarian education, he built a school for children from dissenting families who had been excluded from Anglican institutions. He campaigned for sanitary reform and set up a public dispensary. He ran an anti-Corn Law campaign. Other projects were more visionary than feasible. He built a teetotal Working Men’s Club to lure labourers away from pubs, set up an allotment scheme so that they could produce their own food and established a co-operative store to undercut local shop prices. Unfortunately, the working classes of Coventry did not share Bray’s ideas about how they should live. Both the club and the gardening scheme failed through lack of support, while the store was forced to close by local shopkeepers determined to retain their monopoly.

Bray’s generosity and intellectual open-mindedness – many called it sloppiness – meant that he attracted friends easily. Rosehill had quickly become established as the place where any visiting reformer, philosopher or thinker could be assured of a warm welcome. Indeed, said Bray in the puffed-up autobiography he wrote at the end of his life, anyone who ‘was supposed to be a “little cracked”, was sent up to Rosehill’.1 During these years Mary Ann met virtually everyone who was anyone in free-thinking, progressive society. The socialist Robert Owen, the American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson and the mental health reformer Dr John Conolly were just a few of the people who took their turn sitting on the bear rug which the Brays spread out in the garden every summer. Here, under a favourite acacia tree, they spent long afternoons in vigorous debate, intellectual gossip and various degrees of flirtation.

For just as the Brays challenged conventional thinking in every area of life, so their attitudes to marriage and sexual love were markedly unorthodox. Nor was this openness confined to daring chat. As people who thought deep and hard about how to live, they had come to the conclusion that the monogamy demanded by the marriage vows did not suit human nature, or at least did not suit theirs. Although enduringly attached to one another, both had taken long-term lovers.

Just how this arrangement had come about, and how openly it was acknowledged by others, is obscured by the reticence which the couple were obliged to observe in order to remain active in Coventry public life. Indeed, the main account of their irregular marriage was written down in code and not untangled until the 1970s. The stenographer was the phrenologist George Combe, who examined Bray’s head for lumps and bumps in 1851 and concluded that his ‘animal’ qualities were impressively predominant. Probing further, Combe extracted the following confession from his friend: ‘At twelve years of age he was seduced by his father’s Cook and indulged extensively in illicit intercourse with women. He abstained from 18 to 22 but suffered in health. He married and his wife has no children. He consoled himself with another woman by whom he had a daughter. He adopted his child with his wife’s consent and she now lives with him. He still keeps the mother of the child and has another by her.’2

This makes sense of some odd references in Mary Ann’s letters to Cara Bray during May 1845. Writing from Coventry to her friend on holiday in Hastings, Mary Ann says reassuringly, ‘Of Baby you shall hear to-morrow, but do not be alarmed.’3 A couple of days later she writes, ‘The Baby is quite well and not at all triste on account of the absence of Papa and Mamma.’4 Whoever this baby was, it did not last long at Rosehill. A month later an entry in Cara’s diary suggests that the baby was removed from the household. Clearly this first attempt at adoption had not worked out. Baby’s real mother may have wanted her back or perhaps Cara, while dedicated to young children through her teaching and writing, did not take to this particular infant. An attempt the following year with another baby, sister of the first, was successful and this time the Brays adopted Elinor, known as Nelly. Over the years Mary Ann became attached to the girl and when news of her early death came in 1865 it touched her deeply.

The fact that the first baby had been returned to its mother suggests that the Brays’ family life did not run as rationally or smoothly as Charles liked to believe. Although the details are sketchy, it appears that for a time he tried to get the children’s mother, Hannah Steane, to live at Rosehill as nursemaid. One version has Cara accepting this, but changing her mind when Hannah produced an illegitimate son, named Charles after his father. Henceforth Hannah, now reincarnated as Mrs Charles Gray, wife of a conveniently absent travelling salesman, was established in a nearby house – into which Bray could slip discreetly – with her growing family, five excluding Nelly.5

Cara’s answering love affair was more circumspect. According to a gossipy report from her sister-in-law in 1851, ‘Mrs Bray is and has been for years decidedly in love with Mr Noel, and … Mr Bray promotes her wish that Mr Noel should visit Rosehill as much as possible.’ Edward Noel was an illegitimate cousin of Byron’s wife, a poet, translator and owner of an estate on a Greek island. He was also married with a family. Whether he and Cara became physically intimate is not clear: one version maintains this was an unreciprocated passion. All the same, once Noel’s wife died from consumption in 1845, the way was clear for him to become a familiar fixture on the edge of Rosehill life.6

The Brays’ was the first of three sexually unconventional households which had a great impact on the young Mary Ann, whose romantic experience at this point was confined to a crush on her language teacher. Later she would find herself in a curious ménage à quatre with John Chapman, the publisher with whom she boarded in London during the early 1850s. And her subsequent dilemma over whether to live with George Henry Lewes was the result of his inability to divorce on the grounds that he had condoned his wife’s affair with another man.

It would be good to think that these open marriages were founded on a principled rejection of the ownership of one person by another, and in particular of women by men, of the kind which John Stuart Mill would set out in The Subjection of Women in 1869. But in fact there was more than a whiff of male sexual opportunism and hypocrisy about the various set-ups. Charles Bray, after all, maintained in public that ‘Matrimony is the law of our being, and it is in that state that Amativeness comes into its proper use and action, and is the least likely to be indulged in excess’,7 yet he did not confine himself to adultery with Hannah. There were rumours that ‘the Don Juan of Coventry’ had previously enjoyed an affair with Mary Hennell, one of Cara’s elder sisters. And there was even a suggestion that he and Mary Ann became lovers at some point. Certainly Maria Lewis objected to the way the two clung together and Sara Hennell admitted after Mary Ann’s death that she had always disapproved of the girl depending too much on male affection – perhaps specifically on the affection of her brother-in-law.8 Bessie Rayner Parkes, who was later to become one of Mary Ann’s best friends in London, certainly always believed that Mary Ann and Charles Bray had been lovers.9

Cara Bray, too, was inconsistent on the question of marital fidelity. Although she allowed her husband to have affairs and was herself at least emotionally intimate with Edward Noel, she reacted with Mrs Grundy-ish horror when Mary Ann went to live with George Henry Lewes in 1854. For five years she refused to communicate properly with her friend, let alone to see her. That a woman as progressive and principled as Cara should display such embarrassed confusion over sex outside marriage is a reminder of how deeply entrenched were codes of respectable behaviour – especially female behaviour – in even the most liberal Victorian circles.

Although the Brays’ attitude could seem contradictory, in other lights it was subtle and realistic. Just as Mary Ann had learned during the holy war that spectacular rebellion is often the result of wilful egotism, so the Brays realised that there was little to be gained by publicly embracing the open relationships advocated by their friend the socialist Utopian Robert Owen. They preferred to remain within society and work for its improvement, rather than withdraw to an isolated and principled position on its margins. Whether the world thought them scandalous or hypocritical did not concern them. It was this example of adherence to a complex inner necessity, regardless of how one’s behaviour might be interpreted, which Mary Ann now absorbed. It would stand her in good stead in the years to come when she lived with Lewes and, on his death, went through an Anglican marriage service with John Cross. Her apparent inconsistency bewildered family and friends. Isaac Evans was scandalised by the union with Lewes, but appeased by the marriage to Cross. Her old friend Maria Congreve, on the other hand, was serene about Lewes, but disappointed by what she perceived to be the hypocrisy of the 1880 wedding service. In these apparent switches of principle Mary Ann demonstrated her determination to live flexibly according to the fluctuations of her own inner life rather than in observance of other people’s needs and rules.