Полная версия

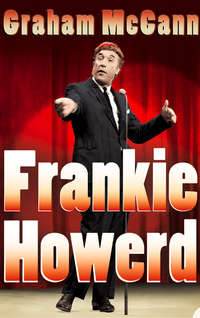

Frankie Howerd: Stand-Up Comic

In an office elsewhere in the building, a visiting booker â there doing business on behalf of a major London agency â grew curious as to what, and more importantly who, was causing so much noise in the auditorium. Setting off along the corridor and down the stairs, he managed to slip inside the door at the back of the theatre and stood there to watch the remainder of Howardâs act.

When it ended, the booker, who had been greatly impressed, raced backstage. âWho represents you?â he panted. âNobody,â replied Howard, trying hard not to sound bitter. âIâm with the Jack Payne office,â the man announced. âWould you like us to represent you?â

Howard, who could still recall with a shudder that awful night at the Lewisham Hippodrome when he had shared the stage but none of the applause with the hugely popular Jack Payne and his band, was incredulous. Looking this stranger up and down for a few seconds â taking in the scuffs on the toes of the old shoes, the deep creases all over the trousers, the stains on the front of the open-necked shirt and the beads of sweat that were now sliding down the brow â he came perilously close to concluding out loud that the whole thing must be some sort of sick joke.

It soon became apparent, however, that the stranger was being serious. âYouâll have to see Frank Barnard,â he added matter-of-factly. âHeâll want to see your act.â Howard, now blushing beetroot-red and starting to lose control over his stutter, managed to reply: âOf course ⦠Yes ⦠Um ⦠Yes ⦠Whoâs he?â

Informed that Frank Barnard was Jack Payneâs general manager, Howard then asked where he could expect the great man to go to see him perform. âIn his office,â he was told. âHis office!â a patently horrified Howard shrieked. âI c-canât perform in an office! I need an audience.â After being told, somewhat tetchily (âLook, sonny â¦â), that Mr Barnard â a hugely experienced and no-nonsense old Geordie â already had more than enough people to see, he was handed his final chance: âAre you interested, or arenât you?â This time there was no hesitation: âYou bet I am!â The stranger shook his hand and smiled: âThen you will perform in his office.â

Howard was left in a daze. Even the daunting prospect of another audience-free audition failed to dampen down the tremendous feelings of elation: his talent had at last been spotted, and, on the very day that he had contemplated abandoning his long-cherished ambitions, he was finally getting his chance. Just before the unexpected meeting had ended, Howard suddenly realised that, throughout all of the heightened confusion, anxiety and excitement, he had not yet asked the visitor his name. âItâs Stanley,â the stranger revealed. âStanley Dale.â10

Howard would always claim, on the basis of this encounter, that Dale was the man who discovered him, but this was not strictly true. Dale may have been the first person from the agency to knock on the performerâs dressing-room door, but it was one of his superiors within the Jack Payne Organisation, the production manager Bill Lyon-Shaw, who had made the actual discovery.

Lyon-Shaw â responding to a tip from a talent scout â had gone down to the Stage Door Canteen on that particular day alongside Jack Payne to take a look at a promising young comedian and impressionist by the name of Max Bygraves. When they arrived, Lyon-Shaw noticed that Frankie Howard was also on the list of artists who were due to appear:

I said to Jack, âOh, God, I know that chap, Iâve seen him before.â Iâd actually seen him a few years before, during wartime, in a little concert party in Rochford. I used to live in Southend, you see, and a lady whom I knew there called Blanche Moore â who never gets the credit she deserves for finding Frank â had written to me and said, âIf you ever get a chance to come back again to Southend, you must come down and see my concert party. We have a very funny man called Frankie Howard.â So, one leave weekend, I went down, and saw this grotesque, in Army uniform, come on to the stage, do a whole lot of âooh-aahsâ and the odd âoh, no, missusâ, tell mostly Army-style jokes and then he ended up with the song âThree Little Fishesâ â which, of course, was unusual and very good. So at the Stage Door Canteen, after weâd seen and liked â and decided weâd book â Max Bygraves, I said to Jack Payne, âLook, this Frankie Howard: heâs quite funny. Letâs just stay a bit and see what you think of him.â And so we stayed and saw Frank, and Jack liked him. He said, âYes, heâs a funny man, heâs different, not at all like the typical slick comic â letâs have him, too.â And thatâs how we got Max Bygraves and Frankie Howard at the same time.11

Whether it was Payne, then and there, who dispatched Dale backstage to make the first official contact with the two new potential clients, or just Dale (in all of the noisy chaos of the moment) acting entirely on his own initiative, remains unclear, but it certainly seems that, during his time inside Howardâs dressing-room, he made no attempt to undersell his own importance within the agency. The fact was that the comedian, who was struggling to believe his luck, was in no state to question anything his visitor said.

Howard was just delighted to have made the acquaintance of Stanley Dale. Admittedly, Dale did not fit the image of the conventional show-business intermediary, but then neither did Howard fit the image of the conventional stand-up comedian. What boded rather well, he reflected, was the fact that their relationship had been founded on such an encouraging convergence of opinion: namely, they both had faith in the star potential of Frankie Howard.

What brought Howard straight back down to earth with an abrupt and painful bump was the thought that this faith would still prove fruitless unless he now went on to win a similar vote of confidence from the notoriously gruff and bluff Frank Barnard. Having failed so many auditions in the past that had been held under similarly cold and unwelcoming conditions, he found it hard now to hold out much hope. Barnard was based in an elegantly capacious set of rooms two floors above Hanover Square in Mayfair. Howard had not even climbed the stairs before his big day started going ominously awry.

Vera Roper, his old friend and stooge, had agreed to accompany him there to provide some much-needed moral support, but, in an unwelcome imitation of her on-stage unreliability, she failed to turn up. The reality was that she had fallen ill, but, as neither she nor Howard owned a telephone, he was left to pace anxiously up and down on the pavement outside, waiting in vain until he very nearly made himself late.

Things went from bad to worse when, reluctantly, he entered the building alone and made his way up to Barnardâs office. âGot your band parts?â barked Barnard from behind a fat and angry Havana cigar. Howard (failing to grasp the full seriousness of the faux pas) confessed that he had not thought to bring any sheet music, but added that he would definitely have arrived with a pianist if only his accompanist had not reneged on her promise to accompany him. This provoked plenty of smoke from the scowling Barnard, whose face had just grown redder than the glowing end of his cigar.

Howard, still somehow oblivious to the obvious danger signs, then pointed a thumb over his shoulder in the general direction of the gleaming new office piano and enquired if there was âanyone around who could play âThree Little Fishesââ for him. This provoked plenty of fire: Barnard, according to Howardâs subsequent embarrassed account, leapt up from behind his desk and promptly âwent berserkâ.12

Launching into a screaming tirade that rocked Howard back in his seat, Barnard told him that he was an unprofessional and impertinent timewaster, unworthy of begging the attention of a bored gallery queue in Wigan â let alone a top-notch metropolitan agent. âHe went on and on,â the traumatised performer would recall, âwhipping himself into a frenzy of near-apoplexy â while I sat literally shivering with terror.â13 Eventually, having shouted himself into exhaustion, Barnard slumped back down into his chair, reached for another cigar, and, waving a hand dismissively in the direction of Howard, snarled: âWait outside.â14 Howard did what he was told.

He ended up waiting outside for four solid hours. During that time spent sitting in silence on his own, he went all the way from quivering terror through meek contrition to angry resentment (âWho the hell does he think he is?â). When, at last, the call came that âMr Barnard will see you nowâ, Howard was firmly in the mood for retaliation: âThe worm not only turned, but grew teeth.â15

âI wouldnât go near that man for all the tea in China,â he screamed at Barnardâs startled secretary. âIâve never been so insulted in all my life, and Iâm not so desperate that Iâll go on my hands and knees to that ignorant pig. Iâd rather not be in show-business at all â and thatâs that.â16

The secretary had obviously been screamed at before, because, once her ears had stopped ringing, she simply patted Howard on the shoulder and advised him to calm down: âSwallow your pride. You may never get this sort of chance again.â Howard, however, was having none of it. With widened eyes and scarlet cheeks, he raged at all the rudeness, injustice and contempt he had suffered, not only that day but on so many, many days before, and then, folding his hands over the top of his head, moaned that he was in no mood now to put right what had gone so horribly, utterly wrong. âHave a go,â said the secretary with a sympathetic smile, and guided him by the arm back to outside the door of the managerâs office.17

So many thoughts, so many options, bounced around in Howardâs head during the handful of seconds that he hovered outside that door: turning the other cheek; punching the other cheek; begging forgiveness; offering forgiveness; speaking his mind; biting his lip â countless ticks and an equal number of crosses. In the end, as he moved to open the door, he settled on speaking his mind.

Crashing into the office and racing straight up to the desk, Howard fixed his tormentor with his very best baleful glare and, stabbing the smoky air with his finger for emphasis, he screeched: âI am now going to make you laugh, you clot. Youâre going to fall about with laughter, you idiot. Because Iâm a very funny man, you oaf!â18 Then he noticed that Barnard was shaking.

He was shaking neither with fear nor rage, but rather with laughter. âThatâs a great act. Great. Itâs a hoot,â he cried, shaking his head, wiping his eyes and smiling broadly. âCan you do any more?â19

Howard, having purged himself of all fury, did a quick double-take and then proceeded to do his proper act. He was more disorientated than genuinely relaxed, but what he did went down so well that Barnard now thought nothing of summoning a pianist to support his rendition of âThree Little Fishesâ. When it was all over, Barnard shook Howard warmly by the hand and assured the exhausted performer that it had been the best âcoldâ audition he had ever seen. He hired Howard on the spot, and then arranged for Jack Payne, the self-styled capo di tutti capi of the post-war Variety world, to see his newest client perform in front of an enthusiastic military audience at Arborfield in Berkshire. Payne (who had no recollection of his pre-war encounter with Howard) arrived in time to watch him steal the show.

Barnardâs initial idea had been for Howard to make his debut as a professional in a relatively run-of-the-mill touring show in Germany. Payne, however, preferred to entrust the monitoring of his early career to Bill Lyon-Shaw, and so he was drafted instead into a far more prestigious new domestic revue by the name of For the Fun of It. Produced by Lyon-Shaw, it boasted such well-established names as the veteran stand-up Nosmo King, the comedy double-act of Jean Adrienne and Eddie Leslie and, topping the bill, the hugely popular singer Donald Peers. Howard joined two other fresh professionals â his fellow-comic Max Bygraves and a contortionist called Pam Denton â at the bottom of the bill in a special showcase for ex-Service performers entitled âTheyâre Out!â

Before the tour began, Howard sat down and invested an extraordinary amount of careful thought into how best to shape his on-stage persona. Desperate to get his professional career off to a strong and certain start, he analysed every aspect of his act â from what he should say (and how he should say it) to what he should wear (and how he should wear it) â and gradually built up an idea, and an image, of the kind of distinctive performer he wanted, in time, to become.

First of all, he reflected on what he most admired about his own comedy heroes â and what he could take from them and then adapt for himself. When he thought, for example, about two of his favourite American performers, Jack Benny and W.C. Fields, he drew inspiration from the prickliness of their respective images (Benny the hopelessly vain and miserly old ham, Fields the drunken and cynical old fraud) and the unusually sharp, self-aware and defiantly pathos-free nature of their material.

What he found especially refreshing was the fact that neither of these fine comedians (in stark contrast to the vast majority of their peers) was enslaved by any obvious need to be loved. It did not matter to Benny if anyone actually believed that he was waited on day and night by an African-American servant (whom he rarely, if ever, bothered to pay), or wore the cheapest toupee in Hollywood, or refused to acknowledge that he had long since passed the age of thirty-nine, or, when asked by a mugger to choose between his money and his life, resented being hurried â âIâm thinking it over!â

Similarly, it did not matter to Fields if the odd person took offence when he knocked back one too many treble measures of bourbon, mumbled something insulting about his wife or aimed a large boot at little Baby LeRoyâs backside. Like Benny, Fields was more than happy to use all of his various foibles, failures and flaws â whether they were real and exaggerated or imaginary and stylised â rather than try, like the more typical kind of comedian, to hide and deny them. The only thing that mattered to this exceptional pair of performers was the number of laughs they were able to generate. It was this attitude â a subtly smart, self-mocking and grown-up attitude â that Howard (the hypocritical âfriendâ of elderly deaf pianists) was ready to emulate.

Turning his attention to the delivery of his material, Howard not only recognised the debt he already owed to George Robey, but also anticipated the impact to be had from studying the style of a more recent favourite, Sid Field. What both of these performers did was to dominate an audience through indirection, preferring to coax the laughs out rather than waiting for them to be handed over on a plate.

Robey had shown how much funnier a clown could be when he acted as if he was labouring under the illusion that he was not actually a clown. Once the first ripple of laughter had rolled towards him from over the stalls, he would stick his hands stiffly on his hips, hoist his nose high up in the air and then snort censoriously: âKindly temper your hilarity with a modicum of reserve.â When this act of pomposity summoned up an even louder and deeper splash of derision, he would, with an air of mounting desperation, urge the audience to âDesist!â â which in turn, of course, would succeed only in prompting an even bigger and more gloriously anarchic burst of playful mockery.

More recently, Howard had been deeply impressed by the classy comic artistry of Sid Field. Like Howard, Field was a peculiar mixture, on stage, of lumbering masculinity and camp effeminacy, of working-class toughness and middle-class gentility â the critic Kenneth Tynan summed it up rather nicely when he likened it to a strangely effective blend âof nectar and beerâ.20

Besides having the knack of being able to act with his entire body â with his nimble hands and knees as well as his brightly expressive face â Field also had a wonderfully playful way with words and sounds and idioms. Ranging freely from coarse, back-throated cockney, through the nasal, drooping rhythms of his native Brummie, to the tight-necked, tongue-tip precision of a metropolitan toff, he turned common words and simple phrases into a special repertory of colourful comedy characters.

Howard adored the way that Field (a master parodist of effete behaviour) needed only to cry a single âBe-ooo-tiful!â or cluck a quick âDonât be so fool-haar-day!â to trigger yet another gush of giggles. He warmed to the performer even more when Field paused to interact with the members of the pit orchestra (âAnd how are yooo today? R-r-r-reasonably well, I hoop?â), boast to an unseen acquaintance in the wings (âDid you heah me, Whittaker?â) and bridle at an imagined insult aimed at him from the audience (âOh! How very, very, dare you!â). Watching him, Howard felt that he had found a kindred spirit, and drew encouragement to follow suit.

When it came to deciding on how he would look, however, Howard had already arrived at some firm and subversive ideas all of his own. Aside from adopting the old Max Miller trick of applying plenty of blue to the lids âto help the eyes sparkleâ,21 he eschewed the custom of caking the face in layers of make-up. He also elected to do without any of the formal, garish or gimmicky styles of dress.

He chose instead to wear an ordinary, off-the-peg lounge suit and plain tie. The colour of both, he decided, would always be a medium shade of brown, because he thought that this could be relied on to be âa colour that didnât intrudeâ: âItâs warm and neutral and man-in-the-street anonymous,â he reasoned. âIf people did notice my suit or tie I thought it would mean that they were not concentrating on my face.â22

He also resolved to dispense with the way that other comedians âframedâ each performance by making a formal entrance and exit. There would be no opening announcements or closing bows from him: he would simply walk straight up to the footlights and start talking â âNo. Ah. Ooh, Iâve had such a funny day, today, have you?â â and then, when he had finished, walk off again in a similar fashion, without ever signalling the presence of quotation marks.

The key thing, he believed, was to create the impression âthat I wasnât one of the cast, but had just wandered in from the street â as though into a pub, or just home from work. And Iâd emphasise the calculated amateurishness of my presence and dress with a reference to the rest of the acts on the bill: âIâm not with this lot ⦠Ooh no, Iâm on me own!ââ23

With all of this, he was almost ready: an unusually informal, ordinary-looking, everyday kind of clown with a plausibly flawed personality, a deceptively artful style of delivery and a rare gift for engaging an audience. There was just one further thing, he felt, that still needed to be done: he needed to change his name. He knew that he was stuck with âFrankieâ, but he decided, none the less, to alter the spelling ofâHowardâ. There were, he was convinced, simply too many other, far more famous, Howards about.

It was, in fact, an erroneous belief: in the absence of both Leslie (the London-bom Hollywood actor who had perished during the war) and Sydney (the portly Yorkshire comedian who had just died in June 1946), there was arguably only one notable Howard present in British show business at this time whose name had truly impinged on the public consciousness â and that was the actor Trevor Howard, who had only recently shot to stardom after playing the romantic lead in the 1945 movie, Brief Encounter.

Even one solitary Trevor, however, appeared to be one too many for Frankie, who proceeded to change the spelling of his surname from âHowardâ to âHowerdâ. Showing himself to be a surprisingly shrewd (if somewhat over-analytical) self-promoter, he reasoned that the minor alteration, aside from helping to distinguish him from the odd stem-feced matinée idol, would have âthe added advantage of making people look twice because they assumed it to be a misprintâ.24

Along with the name change came the invention of what in those days was called âbill matterâ (the slogan that accompanied the name displayed on the poster). There were plenty of examples to study: Max Miller was âThe Cheeky Chappieâ; Albert Modley âLancashireâs Favourite Yorkshiremanâ: Vera Lynn âThe Forcesâ Sweetheartâ; Donald Peers âRadioâs Cavalier of Songâ; Robb Wilton âThe Confidential Comedianâ; and Sid Field âThe Destroyer of Gloomâ. Frankie Howerd, after much careful thought, came up with an epithet all of his own: âThe Borderline Caseâ.25

Now, at last, everything really was well and truly in place. The professional career could commence.

It began in his native Yorkshire, at the massive and Moorish Empire Theatre in Sheffield, on the night of Wednesday, 31 July 1946. Even though he was placed right down at the base of the bill, the act that was âFrankie Howerd: The Borderline Caseâ proved impossible to miss. It was not just that he was different. It was also that he broke every rule in the book â literally.

In How to Become a Comedian (a compact little manual that had been published in 1945), the veteran music-hall star Lupino Lane had spelled out the conventional code of conduct to be followed by any fledgling stand-up comic. Typical of his schoolmasterly instructions were the following sober decrees: âAny inclination to fidget and lack âstage reposeâ should be immediately controlled. This can often cause great annoyance to the audience and result in a point being missed. Bad, too, is the continual use of phrases such as: âYou see?,â âYou know!â, âOf courseâ, etc. These things are most annoying to the listener.â26 Even if some people, at the time, might have resented the intolerant tone, no one really questioned the general advice. No one, that is, except Frankie Howerd.

For all of his myriad insecurities, powerful bouts of crippling self-doubt and near-paralysing second thoughts, when it came to the true heart of his art, Howerd always knew exactly what he was doing â and what he was doing, on that first and on subsequent nights, was walking out in front of as many as 3,000 people and redefining the very nature of what being a stand-up was all about. He made it seem real. He made it into an act that no longer appeared to be an act. He pumped some blood through its veins.

What made the newly professional Frankie Howerd so impressively sui generis as a performer was the very thing that made him seem, as a character, so very much like âone of usâ. He stood out as a stand-up by refusing to stand out from the crowd. For all of his many influences, the thing that really made him special was his willingness to be himself.

âIn those days,â he would recall, âcomics were very precise: they were word-perfect, as though reading their jokes from a script, and to fluff a line was something of a major disaster.â27 Howerd, in contrast, told these same jokes just like the average member of the audience would have told these jokes: badly. He shook up the old patter from within, via a carefully rehearsed sequence of increasingly well-timed stutters, sidetracks and slip-ups, until, eventually, the whole polished package was scratched and then shattered â leaving people to laugh not so much at the jokes as at the person who was trying to tell the jokes.

No audience, back in 1946, had anticipated such an approach, but, when it was witnessed, it worked. It worked, explained Howerd, because, unlike the conventional comedy style, the approach invited identification rather than mere admiration. By daring to appear imprecise, he brought his art to life: