Полная версия

Nature Conservation

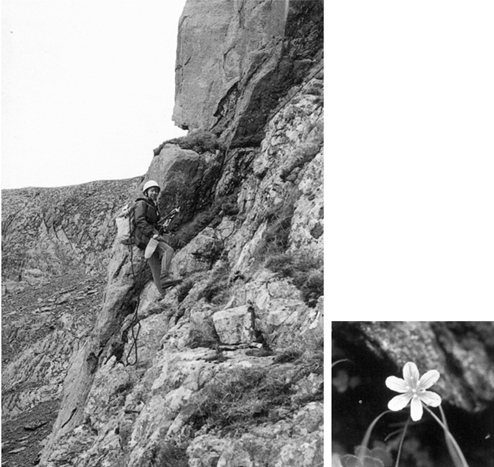

Recording rare flowers: Barbara Jones, a trained climber, surveying the Snowdon lily, Lloydia serotina, (below) on Snowdon.

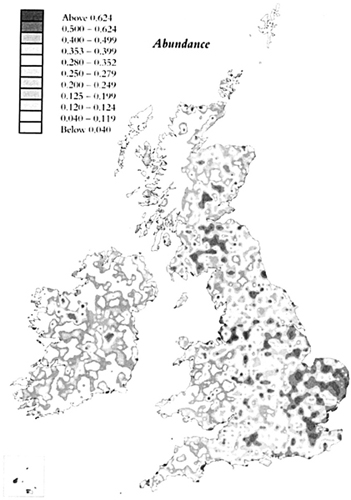

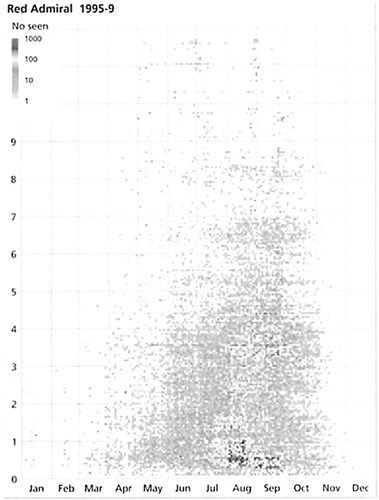

There were also surveys that established a system of baseline monitoring to record how the natural world was changing. A basic ‘phase one’ survey that purported to map all Britain’s natural habitats started in the early 1980s, with the help of the county wildlife trusts. The NCC also started a National Countryside Monitoring Scheme, which compared present and past land use in selected parts of the countryside. A much finer tool for measuring change was handed to conservation workers with the publication, during the 1990s, of the five-volume British Plant Communities, compiled by John Rodwell of Lancaster University, the fruits of a 15-year project to classify all kinds of natural and semi-natural vegetation found in Britain. The vegetation of many SSSIs has been mapped using this National Vegetation Classification, thereby providing a baseline for monitoring change as well as for assessing how much of the different types of vegetation are on protected sites. The species that best lend themselves to detailed census work are birds and butterflies. Birds have long been monitored using the Common Bird Census (now the Breeding Bird Survey) organised by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), along with the regular counts of seabirds by the Seabird Group. The performance of rare birds is the responsibility of the Rare Breeding Birds Panel. For monitoring butterflies, a method was worked out in the 1970s by Ernest Pollard, which involved counting all the species seen along a regularly walked transect. The success of the scheme has meant that fluctuations in butterfly numbers can be recorded, as well as their distribution. Computer techniques have also made possible some novel ‘phenograms’ (see p. 28) combining numbers with dates of emergence. Further evidence of population changes in insects, especially moths, is provided by the ‘Rothamsted traps’ operated under standardised conditions across the country. There has also been a revival of phenology – timing the appearance of flowers or frog-spawn or migrant birds – in relation to climate change.

‘Abundance map’ of the kestrel from The New Atlas of Breeding Birds 1988-1991 showing relative numbers as well as distribution. (By permission, BTO)

From data to action

Surveys and data provision are meat and drink to conservation bodies. It is what they do best. But interesting and often valuable though they are, surveys and monitoring only tell you what is happening. They give a sense of the overall state of health of the patient, but are not in themselves a cure. In practice, looking after wildlife is not based on scientific rationalisation alone, but on negotiation and politics. It is rare that a conservation body has full control over a given situation, even on a freehold nature reserve. Decisions are often made in a cloud of ignorance, or in a spirit of compromise with more powerful interests. Indeed, conservation in practice is to a large extent to do with quarrelling. You make the best case you can, you cite your legal and moral rights, you appeal to the more important party’s better nature. Then, often with the mediation of a third party, you reach the best deal you can, with or without bitter words and recrimination.

‘Phenogram’ of the red admiral butterfly from The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies, plotting latitude at 100-kilometre intervals against months, forms a ghostly outline of Britain. (From Butterflies for the New Millennium survey organised by Butterfly Conservation and Biological Records Centre)

Yet ‘quarrel’ is a remarkably rare word in conservation literature. I think the first time this particular spade was called a spade was in Professor Smout’s book, Nature Contested, published in 2000. More often, like politicians, the parties prefer to sweep disagreements under the carpet, using euphemisms like ‘discussion’, ‘debate’ or even – a popular choice in the 1990s – ‘partnership’. Nature conservation is a quasi-political matter in which the arguing is done as far as possible behind closed doors, and the outcome reported to a supine press with a bland statement. Many conservation bodies have become so used to the self-censorship of uncomfortable facts that they seem to operate on a different plane of reality from the farmhouse or the estate office. Their publications reflect the power of image and presentation in the modern world. It is necessary for conservation bodies to appear slick, dynamic, successful and, above all, relevant. Where the facts of disappearing wildlife appear to contradict this image they can be distorted by the same black arts (‘let’s focus on the positive’) or used to justify an appeal for more money. Ignorance of natural history can be a distinct advantage in this world. Hence, if in the later chapters of this book, I may sometimes seem rather sceptical about the claims of the conservation industry, and its official agencies in particular, it is because I have seen something of this world from the inside. Conservation bodies rarely stoop to deliberate distortion, but their version of events can be coloured by the views of their ‘clients’ and partners, by the attitude of their political masters or by that of a mass-membership. You do not, for example, hear the RSPB talking much about cats, or the Wildlife Trusts about fox hunting. Nature conservation in a crowded island in which all land is property is bound to be difficult, even when everyone agrees that wildlife is a good thing. Conservation can be seen in different ways, depending on how you are affected by it: as a moral absolute, as a cumbersome, bureaucratic restriction, as an unjust imposition by ignorant outsiders, as a potential source of income. I think wildlife is a good thing. Indeed, in my own life I think it is probably the most important thing. I would like my country to preserve as much wildlife and countryside as possible, but without enmeshing rural life in petty restrictions. The standpoint of this book is a love of wildlife but not necessarily conservationists. In these pages you may therefore find a lot of ‘buts’. I hope it will not sound unduly negative. I feel it may be necessary. An account of nature conservation in Britain devoid of individual opinion would be a dull read, indeed not worth reading. I hope this book is worth reading.

2 The Official Conservation Agencies

The British government has always delegated its responsibilities for nature conservation to a semiautonomous agency. The governments of other European countries tend to keep theirs within agricultural departments or National Park bodies. The reason why Britain behaves differently probably lies in our early start and the influence of science in the 1940s (for a good account of this postwar science boom, see Sheail 1998). The founders of the Nature Conservancy, the first official conservation agency in Britain, saw it as a biological service, comparable with a research council or scientific institution, like the Soil Association. They hoped it would develop as a science-based body, using its own research programme to advise government on land-use policies affecting wildlife. As Professor Smout has pointed out, ‘the rule of the bureaucrat guided by the scientific expert has been highly prized in government for most of the twentieth century’ (Smout 2000). They were anxious that nature conservation should not be swallowed up in the departments for agriculture and forestry, where, as a newcomer, and so starting at the bottom of the civil service peck order, its influence would be stifled. Max Nicholson, who directed the Nature Conservancy between 1951 and 1965, had influence in high places and ensured that, as a semi-specialised body, it secured a semidetached status as a research council under the wing of Herbert Morrison, then Lord President of Council. As such, it could not be bossed about by predatory departments of state. There are advantages to ministers in such arrangements. Expertise is ‘on tap, not on top’, and if anything goes wrong it is the agency’s fault, not the minister’s. Dispensable Board chairmen can be sacked, but the minister need not resign. Much of the history of the Nature Conservancy and its successor bodies hovers around the tension between the zeal of semiautonomous agency officials and the brake of government (the appointed Councils of these bodies have tended to be part of the braking mechanism rather than the zeal). It is there between the lines of their annual reports and, now that the papers are at last available under the ridiculous 30-year-rule, you can read about the formative years of that thorny relationship in a fine, detailed book by John Sheail (1998). But here I need to skip over those, to many, golden, well-remembered early years with unseemly haste.

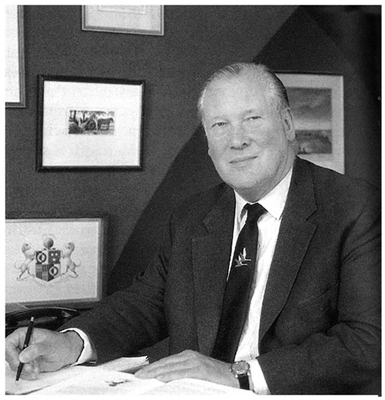

Max Nicholson, Director of the Nature Conservancy 1951-1965. (NCC)

The Nature Conservancy is said to have been the first official, science-based conservation body in the world, and the only one with a large research arm. Although money was always tight, the Nature Conservancy under Nicholson tended to box above its weight. It achieved a good deal, acquiring a nationwide network of National Nature Reserves and research stations, and gaining an international reputation for sound, science-based advice on the management of wild species and natural habitats. I begin the story where Dudley Stamp left off, in 1965, shortly after the Nature Conservancy lost its independence after becoming a mere committee within the newly formed Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). ‘One chapter is concluded,’ wrote Stamp, ‘but there is every sign of a new one opening auspiciously.’

If so, it did not stay auspicious for long. The 1960s should have been a good decade for the Nature Conservancy. The general public had become more ‘environmentally aware’ through events like the pesticides scare (Rachel Carson’s book about it, Silent Spring, became an international bestseller) and the Torrey Canyon disaster in 1967. The threat to our wild places had been underlined by the construction of a nuclear power station at Dungeness (Plate 11) and a reservoir at Cow Green in Upper Teesdale (Plate 13). The Conservancy was closely involved in these issues, and its growing fame was exemplified by the traffic jams on Open Days at Monks Wood Field Station (not to mention visits on different days by Prince Charles and the Prime Minister). However, its status within NERC drew attention to the essential ambiguity of the Conservancy’s role: could a body be scientific, and therefore impartial, and yet advocate a partial view – that conserving nature is a good idea? The Conservancy itself dealt with this duality by dividing its administrative responsibilities under one subdirector (Bob Boote) and its research under another (Martin Holdgate). Unfortunately the Conservancy no longer had full control over its affairs. For example, its budget for nature reserves had to compete for funds with NERC’s broader research, including geophysics, oceanography and the Antarctic. Internal censorship prevented the Nature Conservancy from speaking out on pesticides and other pollutants. Tensions grew in the boardroom, where some members thought it was worth making sacrifices to preserve the link between conservation and fundamental science while others decided that nothing had been achieved by joining NERC, and that the Conservancy would be better off going it alone. The Conservancy’s new director, Duncan Poore, was of the latter view.

Unfortunately there was to be no return to the pre-1965 days: the choice lay between the frying pan of NERC and the fire of a government department. The Conservancy’s committee split, with an influential group voting to leave NERC. A way out of the impasse was offered by the Government’s Central Policy Review under Lord Rothschild – the famous ‘Think Tank’ – which advocated the separation of customer and contractor. As a ‘customer’ of the natural sciences, the logic was that the Nature Conservancy should become independent of NERC, but the same logic prevented it from carrying out in-house research. Rothschild proposed that only half of NERC’s budget should be paid by its parent Department of Education and Science, with the balance found by commissioning research from other government departments. Most of the Nature Conservancy’s own little budget would now come from the new Department of Environment, or, in Scotland, from the Scottish Development Department (SDD). Funds were also transferred from NERC to pay for contract research. By one of life’s little coincidences, the Education Secretary who helped to set up this new Nature Conservancy Council (NCC) was the same person who presided over its demise, 16 years later – Mrs Thatcher.

Rothschild’s report gave the Conservancy the excuse it needed to make public its wish to leave NERC. Government agreed that the Conservancy’s dual role had ‘caused stresses difficult to resolve within the present framework’ (Sheail 1998). Unfortunately the solution, as Government saw it, was to separate science from administration. The Nature Conservancy would become a quasi-autonomous council of the Department of Environment, but its scientific stations would remain behind in NERC. This divorce, representing the exact moment when field-based natural history began to turn into administrative nature conservation, became known as ‘The Split’. The Nature Conservancy Council, usually referred to as the NCC, was established by Act of Parliament in 1973. Its first chairman was a Whitehall mandarin, Sir David Serpell, lately Permanent Secretary at the DoE. He promised to run the new agency on ‘a loose rein’ (which fooled nobody). As a sop to anguished pleas that the NCC must retain some scientific capacity to function properly, it was allowed to keep a small in-house team of scientists under a ‘Chief Scientist’, a term coined by Rothschild. But their job would be limited to commissioning and keeping abreast of research, rather than doing it themselves. In the meantime, its erstwhile Research Branch was reconstituted within NERC as the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE – now renamed the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology).

The Nature Conservancy Council (NCC)

‘No one was entirely happy with the outcome of the “Split”’ (Sheail 1998). Some saw it as a further demotion that threatened the special relationship between science and land management so carefully fostered by the Nature Conservancy. However, that relationship was already falling apart. While the White Paper ‘Cmd 7122’ had talked up the potential of nature reserves as ‘outdoor laboratories’ and the importance of its advice to land managers, the hard truth was that by the 1970s only a handful of nature reserves were used for fundamental research, and farmers and foresters were not queuing up for the Conservancy’s advice (they had their own scientists). Moreover, the crisis in the countryside was growing and it was no longer a matter of experimenting over the best way to manage a wood or a heath but of saving such places from complete destruction. Inevitably this required a shift in emphasis away from scientific research towards site safeguard, which, unless you happen to manage the land yourself, is an administrative task. Most of the Conservancy’s research budget now went on cheap, low-key surveys that helped to identify or characterise the places that most deserved safeguarding. Consequently, the split between the NCC and its former science branch broadened into a chasm. ITE gradually ceased to be a significant part of the nature conservation world – to the deep regret of many of its staff, which included New Naturalist authors like Ian Newton, R.K. Murton and Max Hooper.

The 1970s were a bad decade for the natural environment. In Britain, Dutch elm disease and the removal of hedges created stark, arable landscapes, while in the uplands blanket afforestation transformed many square kilometres of open country into sepulchral timber crops of introduced spruce, pine and larch. Limestone pavements were smashed to bits to adorn suburban gardens and corporate offices. The Norfolk Broads, still crystal clear in the early 1950s, became clouded with silt. The heaths went up in flames during the drought years 1975 and 1976, and, apart from the mountain tops, there seemed to be hardly any wild land that agricultural grants could not convert into profitable farmland. Hence, the NCC was overstretched, using what small authority it had to oppose harmful developments, reach agreements and establish nature reserves. On occasion, it stepped back from events to appraise the situation. In 1977, for example, it published a ‘policy paper’, Nature Conservation and Agriculture, containing the NCC’s thoughts on how to reconcile increasing food production with the maintenance of ‘Britain’s rich heritage’ of wildlife. Essentially the message was that, while vast amounts of public money were helping farmers plough and drain the land, the incentives to preserve wildlife were negligible. You did not have to travel far to see the consequences. A second policy paper, on forestry, was shelved after reported disagreements on the NCC’s Council, which contained members with vested interests in forestry.

In 1977, the NCC at last published A Nature Conservation Review, edited by its Chief Scientist, Derek Ratcliffe, describing the range of wildlife and natural vegetation in Britain, and singling out the 735 best examples of coast-lands, woodlands, lowland grasslands and heaths, open waters, peatlands and upland habitats, all graded according to their international, national or second-string importance. The Review was, and remains, an astounding tour de force, combining a rationale for site selection with a kind of Domesday Book of Britain’s wild places (though, as Jon Tinker pointed out in New Scientist, it had taken eight times as long to produce as the original Domesday Book!). The original purpose of the Review had been to provide a reasoned ‘shopping list’ for nature reserve acquisition. Because of the obvious sensitivities involved – for by no means every landowner would have been delighted to find his property on the list – this aspect was played down, and the Review was presented to the public as a reference book of important biological sites. In commending it in these terms, the Ministers for Environment and for Education and Science were careful to avoid committing themselves to any particular action. The Review sparked no change in environmental policy, but it did form a necessary reference point for site protection. Without some means of assessing the relative importance of wildlife sites, the NCC would be blundering in the dark.

The second key NCC document was its long-term strategic review, published in 1984 and entitled Nature Conservation in Great Britain (‘NCGB’). It was in part an assessment of the successes and failures of the nature conservation movement, and in part a set of ground rules for the future. The failures outnumbered the successes by 21 pages to five, and any impression given by the glossy pictures of a healthy, vital natural environment was contradicted by the lowering bar graphs that showed ‘with stark clarity’ how far wildlife habitats had diminished during the past half-century – a loss of 40 per cent of lowland heaths, for example, and an incredible 95 per cent of ‘lowland neutral grasslands’. Behind the statistics lay a detailed analysis of habitat loss undertaken by Norman Moore – but, as it happened, ‘NCGB’ proved to be the only opportunity to publish any of it. Perhaps Council thought it might depress the minister. The real significance of the review lay not so much in the detail but in its heightened sense of conviction. For the first time the NCC explicitly recognised nature conservation as a cultural activity, and not merely as pure or applied science. ‘Simple enjoyment and inspiration from contact with nature’ was not a partisan activity: it concerned us all. It followed that we should conserve nature in the same way that we take care of other essentials like air and water. ‘Nature conservation has in the past sometimes conducted its business on too apologetic and timid a note’, declared the NCC, looking back at its own history. Timidity had too often meant surrender. ‘We need to play a hard but clean game for our side,’ said the NCC’s new chairman, William Wilkinson. So there were now ‘sides’, us against them. The strategy was heartily supported by most of the voluntary bodies, who rightly saw it as a challenge, heralding a significant change of policy, and expected NCC to honour its brave words to the letter. But in the freewheeling climate of the 1980s, having the courage of your convictions meant having to fight for them. The five years of corporate life left to the NCC were hard ones, and led straight to its destruction.

There were really two NCCs, separated by the watershed year 1981 in which the Wildlife and Countryside Act reached the statute book. The pre-1981 NCC was a fairly low-key organisation with a staff of about 500 dispersed thinly about Britain, struggling along on an annual budget of about £6 million (the NCC had scarcely any income or assets). It advised government on issues affecting wildlife, commented on local plans and developments and grant-aided worthy projects, but was rarely in the headlines. The man in the street had never heard of it, which is not to deny that the NCC achieved a great deal on very little.

Sir William Wilkinson, chairman of the NCC 1984-1991. (English Nature)

The post-Act NCC took a little while to get going, but it became another organisation entirely, more powerful, more centralised, and often in the headlines, especially in Scotland. By 1988, the NCC had 780 permanent staff with a sixfold budget increase to £39 million. An enforced move in 1984 from the old Nature Conservancy’s stately quarters at Belgrave Square to a modern office block in Peterborough gave the organisation a chance to centralise its dispersed branches – an England headquarters at Banbury, scientists at Huntingdon, geologists at Newbury, publicists and cartographers at Shrewsbury were all sucked into Peterborough. The organisation also became computerised and corporatised. Corporate planning was introduced in 1985, requiring staff to complete monthly time records, recording (in theory at least) every half-hour of activity. The Act made nature conservation much more expensive. By 1988, nearly a quarter of the NCC’s budget was spent on management agreements on SSSIs.

The Wildlife and Countryside Act distorted the NCC’s activities for nearly a decade, as its regional staff struggled to notify SSSIs and negotiate agreements over their safeguard. Land not notified as SSSI became known as ‘wider countryside’, and there was little enough time to devote to it (with the honourable exception of urban conservation, largely a one-man crusade by George Barker). Unfortunately, the wording of the Act forced the NCC to adopt a heavy handed approach on SSSIs, in which an owner or tenant would be presented with a formidable list of ‘Potentially Damaging Operations’. Permissions to carry on farming in ways that did not damage the site’s special interest were called ‘consents’. This sort of language understandably put people’s backs up, as did the fact that there was no appeals system and the conviction that notification would lower the land value. Suspicion and potential hostility could be mollified by the farm-to-farm visits of the NCC’s regional staff, who were generally speaking more charming and persuasive than the documents they had to deliver. To the extent that the Act was a success it was theirs, not that of the politicians who created a botched system, nor the civil servants and lawyers who insisted on its rigid application. The local NCC staff rapidly learnt that the only way to make the Act work was by goodwill – hardline interpretations of the law and threats of prosecution simply alienated people, and got nowhere.