Полная версия

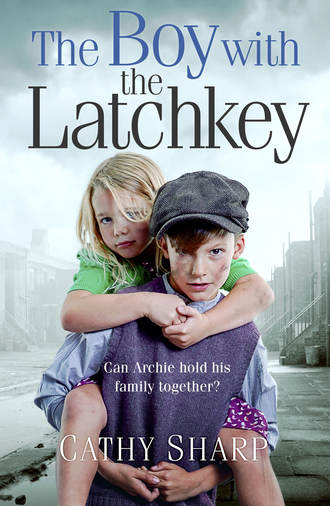

The Boy with the Latch Key

‘I’m going to night school,’ she announced when they sat down at their table again with the fresh coffees Billy had bought. ‘I’m going to try and sit my GCEs so that I can train as a teacher …’

Billy looked stunned for a moment, then, ‘Is that what you really want? To be a teacher? You know it will take ages doing it that way, don’t you?’

Mary Ellen nodded, the doubts already beginning to crowd in on her. She wasn’t sure why she’d suddenly made up her mind to do it, though she’d been thinking perhaps she might for ages.

‘I might not be good enough, but I think I should try – don’t you?’

For a moment he didn’t answer and her heart sank. Rose was going to be against her, and if Billy also said it was daft she didn’t think she would be strong enough to proceed on her own.

‘I think if it’s what you really want you should try,’ Billy said a little reluctantly. ‘It means I shan’t see so much of you …’

‘I’ll only go twice a week,’ Mary Ellen offered, but she knew it wasn’t just the evening classes. She would have to study hard if she wanted to pass the exams she needed to for teaching college. If Billy had objected she would probably have given in immediately, but he nodded and looked sad.

‘I wish I could get the sort of job that would support us both through you going to college and all of it,’ he said. ‘If I’d got that job with the railways …’

‘Sister Beatrice said you had to take an apprenticeship, and the railway wouldn’t offer you anything, because you were too young,’ Mary Ellen reminded him. ‘Rose was the same with me. They think they know best and they make us do what they want … and it isn’t fair …’

‘No, it isn’t,’ Billy agreed. ‘This is 1955 and we’re young. We’re the future, Mary Ellen. I may not get to be a train driver, but I don’t see why you shouldn’t train as a teacher if you want.’

‘Really?’ She looked at him earnestly. ‘You won’t get angry and throw me over if I can’t always do what you want?’

‘I’d never do that, Ellie. Surely you know there’s never been anyone else for me?’

‘Yes, of course I do,’ she said and clasped his hand, her fingers entwining with his. ‘I love you so much, Billy. I just feel we have to do something with our lives. Do you remember what Miss Angela used to tell us about looking up and reaching for what seemed beyond our reach? We were so eager when we had our teams and earned stars for a trip to the zoo or the flicks. I felt as if I’d lost something when I had to start working in the factory. Oh, I like Sam; he’s a dear and almost like a father to us girls, but I want something better for us – and our children.’

Billy’s eyes were fixed on her face. Their colour seemed intensely green rather than the greenish hazel they usually were; she’d noticed before that they changed colour when he was passionate about something. He had so much life, so much eagerness in him, that she knew he must be frustrated in his job too.

‘I want it too, Mary Ellen,’ he said and his voice sounded guttural as if emotion caught at his throat. ‘I get so mad at times because I can’t do the things I want – can’t give you the life you deserve …’

‘I don’t want things,’ she tried to explain, but knew he didn’t really understand. Mary Ellen didn’t want to better herself because of the money; it was for self- respect, for making life fuller and richer. ‘It’s just that … oh, I suppose it’s a better world for everyone …’

Billy nodded, but she knew he still didn’t see it the way she did. A better world to Billy meant a decent house, good wages and kids that didn’t have to go to school in bare feet and trousers with their backsides hanging out. For Mary Ellen it was more, but she couldn’t explain the mixed-up feelings inside her. She laughed suddenly. What was she thinking? She already had a better life than her mother’s, but there was something inside her that questioned. Surely after the terrible war they’d all endured there should be something more …

After seeing her safely home, Billy was thoughtful as he left Mary Ellen. He kicked at an abandoned pop bottle, feeling moody and unsettled. It was all his fault for letting himself be pushed into a dead-end job. Mary Ellen was right when she said she wanted a better life for them and their kids. He wanted it too, but he didn’t know how to achieve it.

‘Where yer goin’ then, Billy?’

The voice made him pause and then turn reluctantly, because he recognised Stevie Baker from school. He wasn’t one of St Saviour’s kids; his father worked on the Docks and his mother was a waitress in a greasy spoon café. Stevie had left school at fourteen and started work as a labourer for the council. Yet as he looked at his one-time school friend, he saw that Stevie was wearing clothes that proclaimed him as a Teddy boy and, by the look of his jacket, smart drainpipe trousers and thick-soled suede shoes, he’d paid a small fortune for what he was wearing. His jacket was blue, the trousers black and the shoes dark blue. The thin tie he wore with his frilled shirt was also black; like a girl’s hair ribbon but held by a silver clip. His hair had been brushed together at the back in a DA and he could’ve passed for one of Billy’s Rock ’n’ Roll heroes if he hadn’t known him.

‘Home,’ he said in answer to Stevie’s question. ‘I’ve been down the club and now I’m going home.’

‘You still livin’ at that dump?’ Stevie sneered. ‘I should’ve thought you couldn’t wait to get out of that place. It gives me the creeps just to look at it – more like a prison than a home. Mum says it used to be the old fever ’ospital, where they sent folks to die …’

‘It’s all right inside,’ Billy said, defending the home that had given him sanctuary. ‘I can’t afford a room on what I earn as an apprentice – not if I want to save for the future.’

‘More fool you then,’ Stevie crowed. ‘You want ter come down the Blue Angel if you want to see life – and they’re always after blokes to help chuck out the rough element. Ask for Tony and he’ll give yer a job, mate.’

Billy knew about the nightclub and its unsavoury reputation. He’d always steered clear of places like that, but now he was curious. ‘Is that where you earn your money then?’

‘Yeah, that and other places,’ Stevie said, avoiding his eyes. ‘Think about it, mate. I can help yer get some money if you’re willin’ ter work fer it and keep yer mouth shut.’

‘I’m not my brother, and I don’t steal,’ Billy said. ‘I wouldn’t mind an honest job, though.’

‘Plenty of stuff goin’ if you’re not too fussy – I don’t mean thievin’ either.’ Stevie grinned at him. ‘I’ll see yer around then, Billy. One of these days you’ll realise the bastards grind us all down unless we stand up for ourselves …’

Billy stared after him as he walked away. He might envy Stevie his smart clothes and wish he could afford something similar, but he wasn’t willing to do anything dishonest. Arthur had gone down that road, and Billy had vowed he never would. No, he just had to find himself a better job … and soon …

CHAPTER 4

‘What’s up, young ’un?’ Billy asked the next morning when he saw Archie Miller disconsolately kicking a tin can in the street outside St Saviour’s and recognised him as one of the recent arrivals. ‘Shouldn’t yer be at school?’

‘We got a day orf,’ Archie said. ‘I was goin’ down the nick ter see me mother but Sergeant Sallis ain’t there and the other old misery guts wouldn’t let me in.’

‘Does Sergeant Sallis let you visit her?’

‘Yeah, he’s all right,’ Archie said and Billy nodded.

‘I get on good with him,’ he said and grinned. ‘Supposing we nip in the phone box on the corner and give him a ring – ask him to phone the station and tell them to let you in for a few minutes?’

‘Would yer? Thanks, mate, that’s great,’ Archie said. ‘I’ve heard about yer – playin’ football and runnin’ fast an’ all …’

‘Come on then,’ Billy said. ‘I’ll come with yer down the nick if he agrees and back you up …’

Billy opened the door of the phone box and they squeezed in together, Billy asking for a number and putting the coins in when the police officer answered. They chatted for a bit, Archie watching anxiously all the while and then smiling as Billy gave him the thumbs up.

‘Thanks Sergeant, I’ll do the same for you one day.’

‘Just keep your nose clean so I don’t have to arrest you …’

Billy grinned even more as he replaced the receiver and turned to Archie. ‘He’s goin’ to meet us there in ten minutes. He says you can have five minutes and that’s all. He ain’t supposed to do it, but he likes you, Archie – and he don’t think yer mum should be there …’

‘Thanks, Billy. You’re a real mate …’

‘Play football, do you?’ Billy asked as they walked the short distance to the police station. ‘Only, I help Peter to run the football club and we keep it goin’ even in the summer – keeps everyone fit and interested.’

‘Can I join?’

‘Why shouldn’t you?’ Billy nodded and held Archie’s arm. ‘We’ll wait out here until Sergeant Sallis gets here – he’s the best of them, believe me …’

As they stood outside in the rather fitful sunshine, which kept disappearing as clouds scudded across the sky, a rather unkempt-looking man walked out of the side door of the police station and glanced their way. For a moment his eyes dwelled on them thoughtfully, and he half smiled to Archie before moving off. Billy noticed that his walk changed from a brisk stride to a careless shuffle, and his whole demeanour seemed to change as he disappeared down an alley. It struck him as a bit odd, as if the man wanted to be thought something other than he was, but he forgot it as Sergeant Sallis arrived and smiled at them in his friendly manner.

‘Right, I’ll take you in, lad. Billy, why don’t you wait across the road in case Archie needs a hand when he comes out …?’

‘Yeah, all right.’ Billy watched as the two went inside the police station, the sergeant’s hand on the boy’s shoulder. It was rotten for Archie having his mother locked up – especially when even Sergeant Sallis didn’t believe she was guilty.

It was wrong and he felt upset for his new young friend, but there was nothing he could do. Billy couldn’t even find himself a decent room or earn enough to support a wife …

‘Mum … how are yer?’ Archie said as she was ushered in and he saw she was wearing the same dress he’d brought in for her the day after she was arrested. ‘When are they goin’ to let yer out?’

‘It’s you, not yer, Archie,’ she reminded him gently and moved towards him, holding her arms out.

Not usually one for hugs, Archie moved towards her and threw his arms about her, close to tears. He struggled to hold them back because he knew she would cry if he did. This was the second visit since she’d been in here and the first time she hadn’t been able to hold back her tears.

‘I miss you, Mum,’ he said, automatically correcting his speech for her. ‘June is miserable. She wants you home – we both do. I would’ve brought her but Sergeant Sallis says he can’t allow it. He shouldn’t have let us meet, but he’s all right.’

‘Yes, he has been kind,’ she said and smiled through hovering tears. ‘As kind as he can be in the circumstances …’

‘Have they told you when you can come home?’

Her bottom lip trembled. ‘It may not be for a while, Archie,’ she whispered. ‘They got me a solicitor and he says the case will go for trial – but I know he thinks I’m guilty …’

‘Mum! They can’t think that,’ Archie said loudly. ‘You would never do anything bad. I know you wouldn’t …’

‘Keep on believing in me, my love,’ she said in a choking voice. ‘And promise me you will look after your sister. Please, Archie. You have to take care of her until I can get home to look after you both …’

‘Oh, Mum, it isn’t fair. June hates being at St Saviour’s – and I don’t much like it, though it’s better than bein’ on the streets …’

‘You’ll be safe with Sister Beatrice,’ his mother said and stroked his hair back. ‘I wish this hadn’t happened, Archie. Someone hates me – I think Reg Prentice is behind all this, but I can’t prove it … and no one but Sergeant Sallis believes me …’

‘The judge will, Mum,’ Archie said fiercely and hugged her again. ‘I wish I could make him pay for what he’s done – that rotten manager of yours …’

‘Promise me not to do anything stupid,’ she said and kissed the top of his head. ‘You’re like your dad, Archie, and I know you’ll be all right at St Saviour’s. Don’t let them split you up and ask Sister to keep you here in London until I get home – but if they don’t I’ll find you. I promise …’

‘I’m sorry, Archie, but you’ll have to go,’ a voice said from the door. ‘If my chief constable finds you here I’m for the chop. It’s back to your cell, Mrs Miller …’

‘Yes, of course,’ she said. ‘And thank you so much for this …’

Archie stared rebelliously as she was led away, but he followed the police constable who beckoned him and showed him out of the side door.

‘You’re a lucky lad,’ he told him. ‘I wouldn’t have risked my job like the Sarge has … Get off with you now and behave yourself …’

Archie shot him a resentful look and left. He became aware that tears were trickling down his face and brushed them off angrily as he went to join Billy in the café opposite.

‘All right now?’ Billy asked and got up to join him. ‘I’ll take you to meet some of the football team. You’ll be fine with Sister Beatrice and if there’s any justice your mum will be out afore you know it …’

‘Ah, Nancy,’ Beatrice said as the girl knocked and then entered her office. ‘Is everything all right?’

‘Yes, thank you,’ Nancy replied. Her soft fair hair was pulled back into a neat plait at the back of her head and she wore the pink gingham dress that was the uniform of all the carers. She was an attractive girl who could have made more of her looks if she’d tried. Since Nan had left them, she’d unofficially taken over her duties, liaising with Beatrice over the rotas and doing extra duty when needed. ‘I just wanted to let you know that I shall be visiting Terry this weekend.’

‘How is your brother?’ Beatrice felt the tiny prick of guilt she always felt when Nancy mentioned Terry. He was now living in a special home in Cambridgeshire for the mentally retarded, where Nancy said he was happy and content to spend his days. ‘Any change?’

‘Not really,’ Nancy said and sighed. ‘Last time I was down he didn’t know me for the first hour or so and then he came out of his trance and was pleased to see me. I never know for certain whether he will recognise me or not.’

‘That is so sad for you, my dear. I had hoped he might make a complete recovery.’

‘Mr Adderbury explained it to me,’ Nancy said. ‘Terry is blocking the past out of his mind. He isn’t violent these days. Everyone says he’s easy to look after, and he helps the gardeners, but he doesn’t remember much about what happened before they took him to the clinic, and sometimes he doesn’t seem to know me. I think it’s the treatment they gave him when he was first taken in …’

‘Well, perhaps it is better for him, Nancy. If the past hurts too much … not all of us are as strong as you, my dear.’

‘I don’t think about it; it’s over and gone and I’ve put it behind me,’ Nancy said, though something in her eyes told Beatrice that wasn’t quite true. ‘Well, I’ll get on. Tilly is in this morning but she can’t do everything on her own. We’re changing the linen today.’

‘I’m sure you’re very busy,’ Beatrice said. ‘Thank you for reminding me that you will be away this weekend.’

‘Jean said she would come in on Sunday if we need her.’

‘Yes, that would be most helpful, but I doubt we shall need her,’ Beatrice said. ‘Wendy will be on duty and I’m sure we can manage for once.’

Returning to her paperwork after Nancy had gone, Beatrice sighed. Jean Marsh had worked for them as a carer before her marriage, and had two young children at school. She sometimes worked a few hours in the mornings if they were short-handed, but it was a case of balancing the budget. Beatrice was fortunate in her staff, she knew, because they were all dedicated to their jobs and willing to work extra hours, often for no extra money. Wendy would sometimes do the work of the carers if necessary, even though her training meant she should not be asked to do menial work, but she never objected in a case of emergency.

Beatrice’s longest-serving carers were Tilly and Kelly, both of whom seemed devoted to St Saviour’s, and although Tilly had married she hadn’t left them, nor did she intend to until she had children. Kelly had a long-standing boyfriend, but no plans for marriage as far as Beatrice was aware. She supposed it was because both she and her friend had families to look after at home, but neither of them confided in her as Nancy and Wendy did. Nurse Michelle had recently given her a month’s notice, because she was having another child, and that meant Beatrice would have to try and find a replacement. It was so difficult to find a good staff nurse willing to work at the home. These days they were all busy at the hospitals, perhaps because nursing wasn’t as popular an occupation with young girls as it had once been. Beatrice had read something about nurses from overseas wanting to come to Britain and she wondered if perhaps she might be luckier if she took on a nurse from another country – and yet there might be difficulty in getting permission for them to work here for more than a few months.

If Angela were here she would know exactly what to do about that sort of thing. Beatrice had resented it when she’d first been appointed as Administrator for the orphanage but she certainly felt the lack of Angela’s organising skills …

A knock at her door made Beatrice look up. Most of her staff simply knocked once and put their head round the door, but this person had knocked twice and was obviously waiting for an invitation to enter.

‘Come in then,’ Beatrice said impatiently. She wasn’t really surprised when Ruby Saunders entered. The young woman was wearing a brown pleated skirt and a fawn jacket over a brown jumper. Her dark-brown hair was dragged back into a tight knot and she’d clipped it firmly back with brown slides. Her complexion was pale and she wore only the faintest smear of pale-pink lipstick. She certainly wasn’t vain about her appearance, that much was apparent, because underneath those dowdy clothes and awful hairstyle there might have been an attractive woman.

‘Ah, Miss Saunders, what may I do for you?’

‘I wondered if you’d heard about Mrs Miller.’

‘Mrs Miller?’ Sister Beatrice frowned as she sought for clarification. ‘Ah, I believe you mean the mother of those children we had brought in last month … Archie and June? No, I don’t believe I’ve heard anything – why?’

‘She’s been committed for trial next week, which means she will almost certainly be given a prison sentence.’

‘You can’t be sure the woman is guilty …’

‘They wouldn’t have brought a trial if they weren’t pretty sure of a conviction,’ Ruby said. ‘It means those children will be without a mother for some time – what shall you do if she’s sent to prison for a long term?’

‘I hadn’t considered it,’ Beatrice said. ‘They will stay here until I’m certain of the outcome and then … well, we may have to send them on to Halfpenny House.’

‘Did you know the Miller girl has been in a lot of trouble at school? She broke a window yesterday by throwing a stone at it and she hit a teacher with a ruler when she was disciplined for bad behaviour.’

‘That was unfortunate,’ Beatrice frowned. ‘I dare say she is very unhappy at what has happened to her. Her mother has been forcibly taken from her and she must wonder what is happening to her life. My carers haven’t reported bad behaviour here at St Saviour’s.’

‘Well, I thought you should know,’ Ruby said. ‘If such behaviour isn’t stopped immediately she may become uncontrollable and once they start down the slippery slope they end up before the courts. Perhaps you should have a quiet word, unless you would prefer me to speak to her?’

‘I believe I am capable of looking after the children in my charge, Miss Saunders. Leave it to me if you please.’

Ruby shrugged her shoulders. ‘Well, you’ve been warned. Some of these girls are devious, Sister Beatrice. I saw June talking with Betty Goodge yesterday morning and it made me wonder; Betty is a troublemaker and a bad influence on others – I’ve never been in favour of mixing your children and my offenders. Some of my girls are not a good influence. You might be well advised to move the girl before she gets into real trouble.’

‘Thank you for your advice, which will be considered,’ Beatrice said coldly. Did the woman think she’d been born yesterday? ‘Is there anything more you wish to discuss concerning my children?’

‘No. I just feel you would be better advised to move her or to think about fostering. June needs parents to keep her in order and her mother clearly cannot cope. She’s been allowed to get out of hand and …’ Ruby was silenced as Sister Beatrice rose to her feet. ‘Well, it’s just my advice, for what it’s worth …’

‘Quite.’ The one word was quelling.

Ruby’s cheeks turned dark pink and she turned and left without another word. Beatrice fought for calm. She didn’t know when she’d felt angrier. These people just couldn’t help interfering, making difficulties where none existed. Anyone would think she’d never dealt with a difficult child in her life! No one could have been a bigger rebel than Billy Baggins when he first arrived, and look at him now … He’d certainly repaid the care he’d been given in many ways, and that was why she was disinclined to ask him to move on, even though he ought to have gone long ago. However, he helped out with the older boys, getting them interested in football and athletics and keeping them out of trouble.

Still, there was no sense in ignoring the warning. She would speak to Wendy and Nancy about June and her brother. It was at times like these when she missed Nan. Her old friend had a wise head and they’d often discussed the difficult children, but like Angela, Nan had her own life these days …

Leaving the paperwork on her desk, Beatrice decided to take a walk round the home. It was by quietly observing the children at their work and play that she made her own decisions. Obviously Archie and June Miller would not be able to stay here if their mother was sent to prison long term, because few of the children did these days. St Saviour’s did a very necessary job of taking in frightened, anxious children, reassuring them, making them understand that a new life awaited them at Halfpenny House and then sending them on. However, Beatrice would do her utmost to make certain that the brother and sister stayed together …

Ruby made herself a coffee in her office and glared at the dividing wall between her and the orphanage next door. Sometimes it made her as mad as fire to see the way that lot went on, heads in the clouds as if all children were little angels who must be treated like fine china. Talk about a dinosaur! Sister Beatrice should have been shipped back off to her convent years ago in Ruby’s opinion. Stuffy old trout! Ruby had only been trying to give her good advice, to prevent a girl on the edge from slipping over into the abyss, from which it was very hard to climb back. Once the girl had a reputation for being trouble she would find life a lot harder than simply being moved to an orphanage in a pleasant location.

Ruby knew a bit about hardship herself, but she hadn’t gone to the bad, even though she’d had every provocation. She’d had to fight for what she’d got and that didn’t give her much patience with those that had it easy. By the look of her, Sister Beatrice had never done a proper day’s work in her life. Oh, she’d trained as a nurse, but she hadn’t had to struggle every step to claw her way through high school and pass her grades. With Ruby’s home life, she could’ve been forgiven for leaving school at fifteen and taking a job – anything to get away! She hadn’t lain down and wept and felt sorry for herself. She’d passed her exams despite all the stuff she’d had to cope with and, after some years of hard graft, she’d landed a good job with the Children’s Department. An orphan herself, Ruby had lived with an uncle and aunt for four years, until she’d won a scholarship to college. After that, she’d made her own way. Nothing would ever persuade her to live under his roof again. She didn’t even visit her buttoned-up Aunt Joan and she wouldn’t go near him if she were starving! Her uncle was a grubby-minded little man who couldn’t keep his hands to himself – and Ruby should know! She’d had to fight him off since she was twelve.