Полная версия

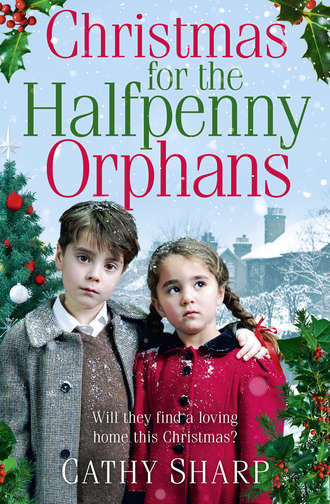

Christmas for the Halfpenny Orphans

‘Yes, of course I shall,’ Sally promised. Angela noticed the girl’s blush as everyone drank the toast and then crowded round her, friends hugging and kissing her and telling her how much she would be missed.

It was true that the young carer would be missed, as much by Angela as any of them, but she knew in her heart it was for the best. To stay on at the children’s home would have brought back too many memories of the man who had filled the children’s ward with laughter when he visited the hospital as a volunteer, the man Sally had hoped to marry until he lost his life in a car accident.

Hearing the phone shrilling, Angela left the staff room where the small party was taking place and ran upstairs to answer it in Sister’s office. It stopped as she reached it and she frowned, wondering if it had been business or perhaps Mark Adderbury … but he would more likely have used the extension in her office had he wanted to speak to her.

A sigh left her lips. It had been a while since Mark had bothered to get in touch, though he’d continued to call in at the home occasionally in a professional capacity. He still nodded and spoke in passing, but his special smile had been conspicuous by its absence. Angela had always thought of Mark as one of her closest friends; when she’d been overwhelmed by grief after her husband of a few months was killed in the war, Mark had been the one who helped her get through it. For a while she’d believed their friendship might develop into something more – but that was before Staff Nurse Carole Clarke came on the scene.

Eager to ensnare a rich husband, the attractive young nurse had made a play for Mark. He’d been flattered at first and they’d gone on a couple of dates, but when he tried to break up with her she told him she was pregnant. Mark had done the honourable thing and proposed. Although she thought he was making a terrible mistake, Angela had felt it wasn’t her place to intervene. But when she caught Carole tampering with records in an effort to discredit Sister Beatrice, and found out that she had lied about being pregnant, Angela had no choice but to get involved. Appalled by his fiancée’s duplicity, Mark had ended their engagement. Carole had stormed out, saving Sister Beatrice the trouble of dismissing her, but her departure hadn’t healed the rift that had opened between Angela and Mark. If anything, he was more distant. It was as though his initial shock over his former fiancée’s behaviour had turned to embarrassment and now he couldn’t bear to face Angela.

In the staff room, Sally’s colleagues were still saying their farewells, but Angela was in no mood to return to the party. Instead she carried on down the stairs, meeting Sister as she reached the hall below.

‘Ah, Angela,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘I was just on my way up to see you. I’ve been speaking to Constable Sallis. It appears they’ve found a couple of young girls in an abandoned house. They’re in a weakened state apparently. He asked if we would take them in while inquiries are made. Naturally, I said yes.’

‘Poor darlings,’ Angela said. ‘How old are they?’

‘He was rather vague,’ the nun said and shook her head. ‘He thinks about eleven, but he isn’t sure about the younger one.’

‘Ah, well, I’m sure we can fit them in somewhere in the new wing. We have so much more room now that we’re able to move in there.’

‘Yes, thank goodness. Mark Adderbury telephoned me earlier. He suggested we have a small party here for the staff to celebrate the opening of the new wing. He thinks it would be a good idea to ask the Bishop to open it for us. Naturally, I agreed, though I do not particularly see the need myself …’ She waved her hand in dismissal. ‘But if the Board think we should …’

Angela noticed the faint sigh. Sister Beatrice was looking pale and tired. A few months previously she had been attacked by an unfortunate and disturbed boy named Terry and though it didn’t seem possible that she would still be affected by a minor injury, it was clear she was no longer the forthright and energetic Sister Beatrice of old.

‘Is anything the matter, Sister? Are you quite well?’

‘Why do you ask? I’m perfectly all right. What nonsense.’ Sister Beatrice walked off; evidently annoyed that Angela should express concern. She prided herself that she was never ill and routinely shrugged off colds that would send lesser mortals to their beds. Angela shook her head and made her way to the kitchens.

The cook, Muriel, was complaining to Nan, who was trying to placate her but without much success. ‘How I’m supposed to manage with that wretched girl late again I don’t know,’ Muriel said. ‘She was away two days last week – and she knows there’s a mountain of work to do today if I’m to bake as well as make jam from those lovely plums and apples we’ve been given. I can make a pudding with some of them, but most of the plums are too ripe for eating.’

‘I expect that’s why they gave us such a lot,’ Nan said.

The comment made Angela smile. As head carer, Nan had no idea how much badgering went on behind the scenes to keep St Saviour’s kitchens supplied. Angela thought the stallholders at Spitalfields’ wholesale fruit market must be sick of the sight of her, but she’d asked them not to throw their surplus out if it was still useable.

‘It might be too ripe for you to sell on, Bert,’ she’d told her favourite wholesaler the previous morning. ‘But we can always use it for jams and puddings.’

‘Anythin’ for you, me darlin’,’ Bert had said, making her an extravagant bow and kissing her hand. He was in his sixties if he was a day, but handsome, with strong grey hair and harsh features that belied his soft heart. ‘I’ll scrounge some boxes of fruit for your orphans, love, don’t you worry.’

In the months since she’d come to the East End of London as the Administrator for St Saviour’s, she’d learned to love the warm-hearted men who worked the fruit and vegetable wholesale market. They’d made several generous donations of fruit and vegetables, and she wasn’t going to allow their generosity to go to waste, despite a girl being late for work.

‘I’m sure Nancy will give you a hand with the fruit, Muriel, and you know how the children love your jam.’ Angela smiled at her. ‘I’ll have a word with Kelly when she comes in, if you like – perhaps I can find out why she is late so often.’

‘We’re so short-handed these days. I really miss that Alice Cobb; she was always ready to help out in an emergency,’ Muriel sighed as she chopped and peeled.

‘Alice stayed on as long as she could after she married that nice young soldier, but she’s a mother now and it’s too soon for her to come back to work,’ Angela reminded her.

‘She had her baby in June, and a lovely little thing she is too. Alice has been talking about coming in for a few hours when she’s ready.’ Nan saw Alice often, now that she’d taken the girl under her wing, and kept them up to date with her news.

‘If you need any help with washing up, I could give you a hand,’ Angela offered. ‘And I’ll take the trays up to the nurses if you like.’

‘Nurse Wendy usually comes down for hers at about ten …’ Muriel glanced at the clock. ‘I’ve got the washing up from breakfast, and then I’ll need a hand if I’m going to get my baking done and that wretched jam – so if you could possibly ask Nancy to come down, please, Angela.’

‘I’ll give you a hand with the washing up,’ Nan said. ‘I’ve got linen to change today, but Jean will manage without me for a while. I shall miss Sally though.’

‘Yes, we’ll all miss her, but you have Tilly Tegg to take her place, and she seems very willing,’ Angela said. ‘Yes, you do need to get your preserves done, Muriel; it will soon be time to think about Christmas again …’

‘Don’t talk about that yet,’ Muriel begged. ‘I’ll soon have to start thinking about making cakes and puddings for Christmas. Thank goodness we’ve got some dried fruit on the shelves this year. Three years ago I had to make them with carrots and prunes to bulk the mixture out and they didn’t taste the same.’

‘Well it’s still only September,’ Angela said. ‘So there’s time yet. I’ll make a tray of tea and take it up for myself, if you don’t mind.’

‘No, certainly not, you get on and do what you want,’ Muriel said, making Angela smile as she remembered how fussy Muriel had been when she first arrived at St Saviour’s.

Angela left the kitchen with her tray and met Nancy in the hall. Terry’s sister had settled well into her new role at St Saviour’s, even though Angela knew she worried about her young brother in the special clinic Mark Adderbury had found for him. Terry was better than he had been, but still not mentally stable enough to be allowed out yet.

Nancy willingly agreed to help with the jam making, and went into the kitchen. Angela pressed for the lift to come down from the next floor. She was lost in thought as it whirred up to her office floor. As she got out and walked past the sick and isolation wards, she saw Mark come out. He stopped, smiled hesitantly as he saw her, and then took the tray from her. Angela went on ahead and opened her office door. Mark brought the tray in and deposited it on her desk. She offered him some tea, but he shook his head.

‘Mustn’t stop long,’ he said. ‘I was thinking I should telephone or come and see you, soon. How are you, Angela?’

‘Very well, Mark – but how are you? I haven’t seen you to talk properly since … oh, after the concert we had at Easter. I understand you were away at a conference over the summer?’

‘Yes, amongst other things. I always seem to be in a hurry these days.’

‘Well, it’s nice to see you …’

‘Actually, the concert was one of the things I wanted to talk to you about, Angela. Everyone was so pleased with that, and it raised much more than the price of the tickets in donations. I was thinking perhaps we might have a Christmas concert this year …’

‘How funny, so was I!’ Angela said, a laugh escaping her. ‘I know it’s too early to be thinking of it yet. Muriel was quite alarmed when I mentioned Christmas – she’s having staff problems.’

‘I expect you have plenty of them here.’

‘It isn’t easy to find reliable staff. And now we’ve lost one of our best girls – Sally Rush is leaving to take up nursing.’

‘How is she these days?’ Mark said frowning. ‘It was a terrible shock losing Andrew Markham that way … he was a brilliant man, both as a surgeon and with those marvellous books of his.’

‘Yes, the children still love them. Nancy told me that some of them ask her why there are no new books.’

‘Nancy seems to be doing well here.’

‘She’s learning a lot, assisting Muriel and helping with the younger children, but naturally she can’t forget poor Terry and what happened. She visits her brother occasionally, but …’

‘Terry’s breakdown was traumatic for everyone.’ Mark seemed intent as he looked at her. ‘And you, Angela? I never seem to find you around these days. You work terribly long hours. You should make time for some fun.’

‘Well, I do, when I can,’ Angela said, ‘but I have other charity work nowadays – meetings I go to in the evenings. I’m only working here this evening because I have to finish a report on—’

‘Not too busy to go for a drink later, I hope?’ He looked at her and Angela was unsure what she could see in his eyes. ‘We really ought to talk …’

‘Oh …’ Angela hesitated and then inclined her head. ‘I should be finished by eight – if you want to meet somewhere?’

‘I’ll pick you up then and we’ll have supper at that pub by the river – we went there once before, if you remember?’

‘Yes, thank you,’ she agreed. ‘I shall be ready by eight and I’ll come down to the hall. It will be nice spending time with you again, Mark.’

‘Yes, I’ve missed our time together,’ he said. ‘I’ll look forward to this evening.’

‘Yes, me too,’ she said, giving him a smile as she watched him leave. It was time she started work on that report, yet she lingered for a moment, thinking about Mark and the way he’d always been there for her until Carole came between them.

As she put a sheet of paper into her typewriter, Angela’s thoughts turned to Kelly, the girl Muriel had complained about so bitterly. She was a pretty dark-haired girl and bright, always friendly when Angela saw her – so why was she proving so very unreliable?

‘Oh, Mammy,’ Kelly Mason said, looking at her mother as she sat slumped in her wooden rocking chair by the kitchen fire. The kitchen looked as if a bomb had hit it, and needed a really good clean. ‘Why didn’t you tell me if you were feeling ill again? I would have done all this last night. I can’t stop now or I’ll be late again and Nan … I mean Mrs Burrows, told me that she will have to let me go if I keep having time off.’

‘You get off then, my love,’ her mother sighed. ‘Make me a cup of tea first and then I’ll get up and see to the bairns.’

Kelly saw the weariness in her mother’s face and sighed inwardly, knowing that she couldn’t desert her mother when she was like this; getting the younger children ready for school would be too much for her. When Mammy started to tremble and took her tea with unsteady hands, Kelly knew there was nothing she could do but stay for another hour or so to see to the children before she left for her work at St Saviour’s.

Running upstairs to pull her siblings from their beds, Kelly was thinking about her job at the children’s home. She loved working there, even though she was only employed in the kitchens as a skivvy, washing up, scrubbing and helping Cook by peeling mounds of potatoes and chopping cabbage or scraping carrots. Sometimes, Kelly thought she would throw up if she saw another carrot covered in mud, because they had to be scrubbed under the tap in the scullery before she could peel them; she hated the ones with wormholes, especially if there was still something inside, and Cook was so fussy about her food. If she found one speck of dirt in the cabbage she made Kelly’s life a misery.

Her sister and brothers squealed as she yanked the covers off them and then physically ejected them from bed; they were lazy devils and did little or nothing to help Mammy, even though Cate was old enough at nine to help with the simple chores.

‘Get up and wash now,’ Kelly said crossly, ‘or you’ll get no breakfast. I’ve got to get to work and I can’t wait about for you. Mammy isn’t well this morning so you can do the washing up before you go to school.’

‘There’s no school today ’cos there’s a hole in the roof and we wus told not to go in,’ her brother Michael complained bitterly. ‘I ain’t goin’ ter get up yet, our Kelly. You’re mean to get on at us like you do.’

‘Well, you may have a day off but I don’t,’ Kelly said. ‘I’m not telling you again. There’ll be toast and dripping and a cup of milk for you downstairs. I’m leaving as soon as I’ve washed up the supper things – and if I find Mammy worse tonight because you didn’t help her, Cate, you’ll feel the back of my hand.’

‘I’ll help Mammy,’ Robbie said. He was only five but more serious than the others and she knew he tried but he couldn’t do much other than set the table or fetch things from the shop.

‘Thank you, Robbie love,’ Kelly said. ‘Make the others help her too and make sure she doesn’t do too much. I’ve got to hurry or I might lose my job.’ She didn’t earn much but even a few shillings extra helped to pay the rent and make sure there was coal for the fire.

She took Bethy from her cot and into the bathroom, washing her face and changing her nappy. Bethy was nearly three and still in nappies; it seemed she wouldn’t learn to use the potty or perhaps Mammy was too tired to train her into it as she had the others. She’d never really been well since the birth of her youngest child.

Kelly ran back downstairs, knowing that her younger sister would get up even if Michael did not. In the kitchen she settled Bethy in her high chair with a piece of bread and strawberry jam; toast was too hard for the little girl and she liked to suck on her bread until it was soft and she could swallow it without having to chew. Kelly wasn’t sure if the child was backward or simply lazy, like most of her family seemed to be. She herself seemed to take after her Irish grandmother who had brought up a family of twelve and never stopped working until she dropped down dead in her mid-fifties of a heart attack.

Almost an hour later, Kelly had fed the baby, brought a semblance of order to the kitchen and abandoned her brothers and sister to their quarrel over who should do what, as she grabbed her shabby coat and left the house. She saw a bus coming that would take her close to Halfpenny Street and ran to catch it, sighing with relief as the cheery conductor collected her fare. At least she was on her way to work and perhaps Nan would let her off as she was only a bit late …

THREE

Angela popped out at lunchtime to pick up some shopping, taking it back to her flat before returning to Halfpenny Street. In the heart of Spitalfields, the street was typical of others in the neighbourhood with its rundown houses and shabby commercial properties. St Saviour’s had started life as a grand Georgian house with gardens at the rear and three floors plus attics above, but it had long ago lost its air of grandeur. People of all nationalities lived and worked in the surrounding streets, which had once formed part of the prosperous silk district, populated first by émigré Huguenots. In later years many Jewish synagogues and businesses had taken the silk merchants’ place, and they in turn had moved on as a variety of new, much poorer inhabitants flooded in. Even on a lovely September day, the street looked grimy and most of the buildings were dilapidated, but what had for a time been the old fever hospital was now a place of hope for the children who lived there. The window frames and doors had recently been painted and it looked more cheerful now that the attic windows were no longer boarded up, the roof space having been turned into two large offices.

On her return, Angela met Staff Nurse Michelle coming downstairs with a tray of dirty cups and plates as she entered the hall, and stopped to speak to her.

‘Is Muriel still behind? I think Nan gave her a hand earlier as Kelly Mason was late again …’

‘Kelly is having a bad time at home,’ Michelle said with a sympathetic look on her pretty face. She was a striking girl with midnight black hair and a pearly complexion. ‘Have a word with her before you think of sacking her, Angela. She isn’t lazy. I think it’s just that her mother can’t manage without her help.’

‘Give me the tray, Michelle. I know you have better things to do upstairs.’

Angela carried the tray through to the kitchen and discovered Kelly talking with one of the newer carers, Tilly. They were sitting at a table drinking tea and seemed intent on their talk until she entered, but their conversation died and she fancied Kelly looked a bit apprehensive.

‘Don’t let me interrupt you,’ she said. ‘I came in the hope of a cup of tea.’

‘I’ll get you one, Miss Angela,’ Kelly said. ‘I’m taking my lunch break, miss, and we were only talkin’ about Ireland. Tilly was telling me her auntie married a man from Derry.’

‘Yes, you’re Irish, aren’t you?’

‘Only on me mam’s side,’ Kelly said. ‘Me dad is English; London bred and born. I was tellin’ Tilly how me mam’s been ill all year and I’ve been lookin’ after her as much as I could—’ The girl broke off, a look of anguish in her eyes. Angela understood instantly, because Michelle had warned her. It explained Kelly’s lateness and constant days off. ‘Only in me spare time, though …’

‘Yes, I see,’ Angela said. ‘Has your mother had the doctor, Kelly? Do you know why she’s so poorly?’

‘He wouldn’t come to us, miss,’ Kelly said. ‘We live in a slum down near the Docks. Dad hoped Hitler would do us a favour and blow the cottage up, but it’s still standin’ and the council say we’re a long way down the list – but it’s damp see and Mam suffers from a heart condition. She feels the cold somethin’ awful – and I think I take after her; it’s why I’m always gettin’ a chill.’

‘Well, we shall have to see what we can do to help your mam,’ Angela said. ‘Would your family move into a better place if one were offered, Kelly?’

‘Oh yes, miss,’ Kelly’s face lit up. ‘Me dad would do anythin’ to make her well again.’

‘I’ll speak to some people I know,’ Angela said. ‘I’m helping a Church charity to provide deserving cases with decent housing they can afford. We don’t have enough houses for everyone and there’s always a long waiting list but … it would help if we had a doctor’s report …’

‘The doctor won’t come to our house; he doesn’t like the area – too many bad folk where we live.’

‘I know someone who will come,’ Angela said. ‘If I have your permission I shall bring him myself, Kelly.’

‘I’ll ask Dad and tell you tomorrow,’ Kelly said and put a cup and saucer in front of her. ‘It’s still hot, miss. We’d only just made it.’

‘I’d better get going,’ Tilly announced and stood up. ‘We’re rushed off our feet today.’

‘Yes, and I must too.’ Angela took a sip of her tea. ‘I should like Dr Kent to see your mother, Kelly; if her health is affected by the damp conditions it will help your family move up the housing list. I can’t promise anything. The charity I help out has to be fair and I’m only one small cog, but sometimes they listen to me. If your mother was better, you wouldn’t have to be late so often.’

Kelly’s cheeks turned even pinker and she hung her head. ‘Thank you, Mrs Morton – and I’ll try not to stop away too much. You see, Mammy has a little one still at home and another three at school, and if she’s ill …’

‘Yes, I do understand, Kelly,’ Angela said, ‘and I shan’t be reporting you to Sister for staying away from work – but you must try to come in on time; you know we need you too.’

‘I could always come in and make up me time when me sister gets home from school – I wouldn’t mind working in the evening to make up for being late. Me da’s home then …’

‘Well, let’s see what we can do for your mother first,’ Angela said. ‘Perhaps there is some treatment that will help her.’

She was thoughtful as she made her way to her office. If Kelly’s mother was suffering from the damp conditions in her slum house then the sooner she was on their list the better. Since the end of the war more and more building was taking place, but it took time to get all the kilns and factories producing at full capacity and progress was slow. So many people had been left homeless that pulling down the old slums that had remained standing was not a priority. In time it was hoped to replace all the substandard housing, but it could take years. It was the aim of the charity Angela assisted to help those who needed it most, but there were so many in bad housing and they couldn’t help them all. In some quarters there was resistance on the part of the slum dwellers themselves, who didn’t want to move out to the suburbs; for this reason, the charity had decided to renovate old properties rather than build new.

Families like Kelly’s were often overlooked, and the terrible poverty they endured often bred cruelty, which in turn led to battered children being brought to their door at St Saviour’s. If Kelly’s mother died, the girl would have to leave her job to look after her siblings or they might end up at St Saviour’s or some other children’s home.

Determined to prevent such a tragedy, Angela resolved to speak to Dr Kent about visiting Kelly’s mother. He was new to the area and keen to get to grips with the poverty and sickness he witnessed on his rounds; Angela hoped that would make him more likely to be interested in the Masons’ case.

Angela had no sooner started typing up her report than the door opened and Sister Beatrice entered. She looked thoughtful and rather anxious, as if something were playing on her mind.

‘Is there anything wrong?’

‘Wrong with me? Why should there be? I’m perfectly well,’ Sister snapped, and Angela wondered what she’d said to upset her this time. She was secretly counting the days to her forthcoming move upstairs to one of the new offices in the attic. Perhaps once their offices were no longer side-by-side and they met only to discuss business they would get on better.