Полная версия

Barefoot Pilgrimage

And something sacred to me then, that I cannot grasp now: a rectangular box. What did it house? It swam to the top when I watched Krapp’s Last Tape. Something intangible but fantastic to me.

There are triangular cartons of milk on a shelf and lessons that don’t include spellings or times tables. Firstly I realised that I was a short-haired girl here and not a boy. It dawned on me at around the same time as I discovered that my desk mate, Julie, with corduroy trousers beneath a skirt, was a girl.

I met my best friend Niamh on my first day and our lives have walked down parallel hawthorn-hedged lanes ever since. Our unrequited and disappointing loves engraved on the seen-it-all-before, though bent in sympathy, secret-keeping trees. Our hands reach out every now and then, and back we go to the field after the drinks cabinet and the Dolly Mixtures, the stone wall and a song about a green puppet called …

Orville?

Yes?

Who is your very best friend?

You are!

I’m gonna help you mend …

Rice Krispies in the bowl but didn’t you eat cornflakes …?

We both call each other Bosom, as in bosom buddies from Anne of Green Gables, and we still do. We grew differently however … Well, let’s just say that she alone grew into our name.

All grown up, we lose each other one day around Grafton Street in Dublin and then simultaneously find each other. She is outside Davy Byrnes. I’m outside The Bailey.

‘BOSOM!!’ we shout and the doorman beside me gives us both a good look over as she crosses to my side.

He says to me with his mobile eyes unblinking, ‘I can understand why she’s called Bosom, but why the hell are you called Bosom?!’

Ah, she’s had her ups and downs, my Bosom. A newspaper got a detail wrong once (it happens sometimes) and gave the ecstatic news that my best friend ‘Busty’ was to be my fourth bridesmaid.

Up the Town

‘Well!’ is how we said hello in Dundalk: an exclamation rather than a question.

An oddly hopeful ‘How are ye?’ when the auto-response was more often than not: ‘Strugglin’.’

Or Dad’s and my favourite: ‘Ah, same ole shit, another day.’

We would later abbreviate this to ‘SOS’.

‘How are you, Daddy?’

‘Ah, SOS, Pandy. How are you?’

And one day, my hand in his, walking up the town, he said to a man going by, ‘How’s the form?’

And I looked up and asked, ‘Has that man got a farm, Daddy?’

We would walk on the dark, cold early evenings, frost steaming from our talk, and do a crawl of the churches to see the baby Jesus in the manger. New born in the hay, in a red glow of light.

And there was the weekly scram to twelve o’clock Mass, for Daddy’s above at the organ, you see, looking through the mirror for our heads bent in prayer. His dark wee angels. If he didn’t spot your head you could allay his suspicion later, with the mention of a bum note peeking cheeky out of Bach. Well, it was bound to be true.

Mammy eventually stopped attending Mass. She said sitting there made her panic.

But now I look back and realise that a lot of people were, in truth, struggling at this time in Dundalk. This was the late 70s, early 80s. The milk at the back of the classroom was necessary. There were a lot of single-parent households with dads away, peacekeeping in the Lebanon. Of course I was a child. I had no real notion, then, of any household being different to our own. One mum at home plus one dad at work until he returned to do the peacekeeping you just couldn’t mute the way you could hers. And to give you a piano lesson.

But it must have been very hard. Years later, I met a girl I’d known at that school who told me of a time when they literally ran out of food and that milk was all they had. I remember a friend of Sharon’s who put me on a stool beside him by our cooker and turned making ‘the thickest ever pancakes!’ into a game.

Pride, it seems, can be the last casualty of poverty. It hurts my heart to think of it now. I didn’t know he was hungry.

Dundalk became a refuge for Catholics who had been burned out of their homes in 1969. The burning of Bombay Street. One of the council estates, Muirhevnamor, became known locally as Little Belfast and it was understood that there were places you did not go, unless you ‘sympathised’.

And then of course the border, the soldiers, and Daddy’s wicked sense of humour. Jim in the back of the car as it slowed … Mum complaining to Dad, ‘Oh Gerry, I hate seeing these men with guns.’

And Daddy responding, ‘Don’t worry, Jean. They only want little boys.’

Poor Jim. That was too bold, Gerry.

Although I can still see the H-block graffiti glaring and desperate on the grey, ominous brick of the tunnel bridge, beneath the train track, generally I was as oblivious to the ongoing conflict as I was to the hunger. Not surprising, really … I was a full and happy child.

But no matter what, you still grow in the soil you’ve been planted in and here, I discovered that morality, right and wrong, can be complicated and confusing.

The Baddies and the Goodies

For some reason, Caroline and myself would often be early for school and we would play with the caretaker, who we loved. Then one day he wasn’t there any more and the Redeemer School was on the news. They had discovered weapons hidden in the roof of the assembly room.

‘But that was a goodie doing the work of a baddie?’

I happened to be born in Dundalk on the day of the deadliest attack of the Troubles in the Republic.

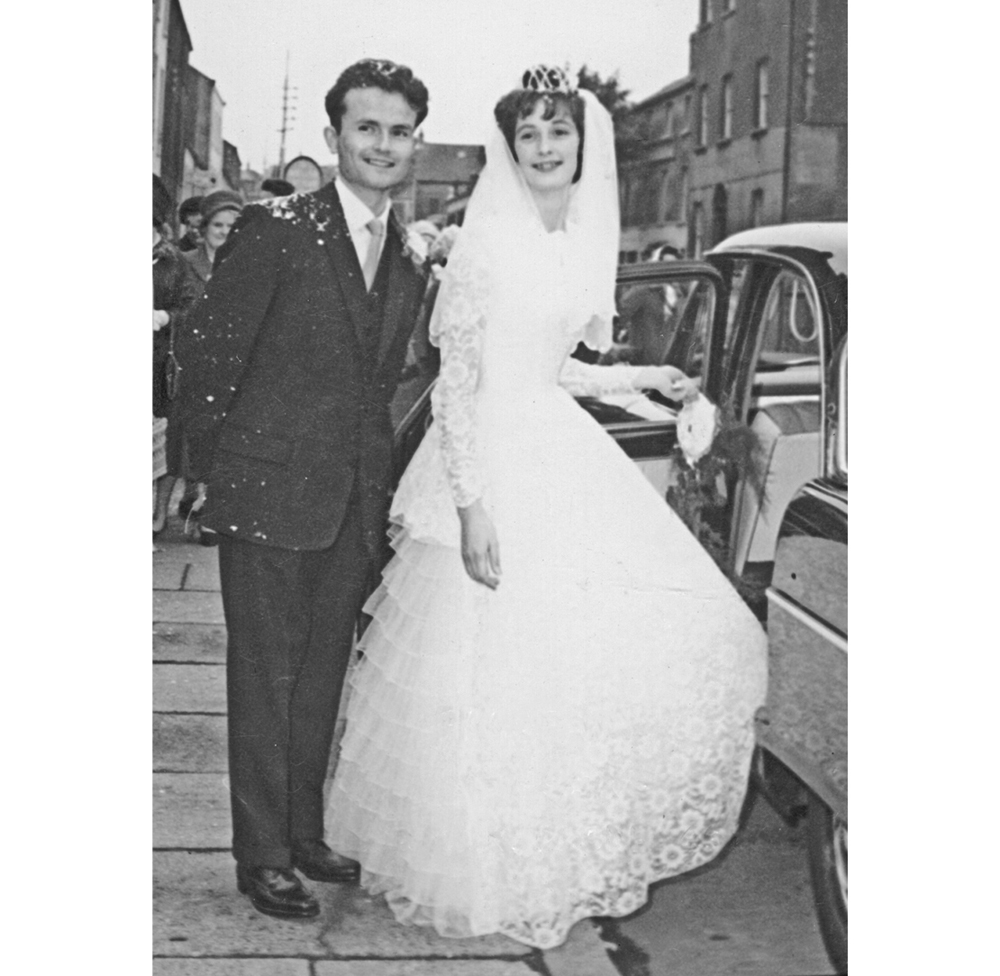

On 17 May 1974, four car bombs exploded at rush hour in Dublin and Monaghan, killing thirty-three people and a full-term unborn child. I have discovered since that my father-in-law, Dermot, just missed being in Talbot Street the moment the bomb exploded. He was to buy a bottle of shampoo for his young wife, Pat, in a pharmacy on North Earl Street, just a hundred yards from where the bomb would go off. But it being a beautiful day, he decided to keep on walking and buy it closer to home. As he turned off Talbot Street on to Amiens Street his ears rang deaf and the ground shook beneath his feet.

Bold Gerry, Baa and the Outstretched Contrite Hand

Once upon a time there lived a husband and a father who had a wicked sense of humour. He was possessed of many gifts, not least of all being sporty as a youth. However, one day, his curious, rebellious soul led his fit but mortal coil into his dying sister’s forbidden Victorian sick room. She, Eileen, a dark-haired white form, lay on the bed with a bleeding cough and a fire in each cheek. Some time later, Eileen having departed, Gerry (for that was the name of the young man) found himself chronically tired and not at all able for his Gaelic football or his tennis. When his new friend Dolphin Cough, Eileen’s old bestie, started pulling red flags from his mouth, he was quickly dispatched to the sanitarium for eleven months wherein he made his living, not dying, as a bookie and had a romance with a nurse. And luckily for all of us (or was it?) was just in time for Waksman’s cure: streptomycin.

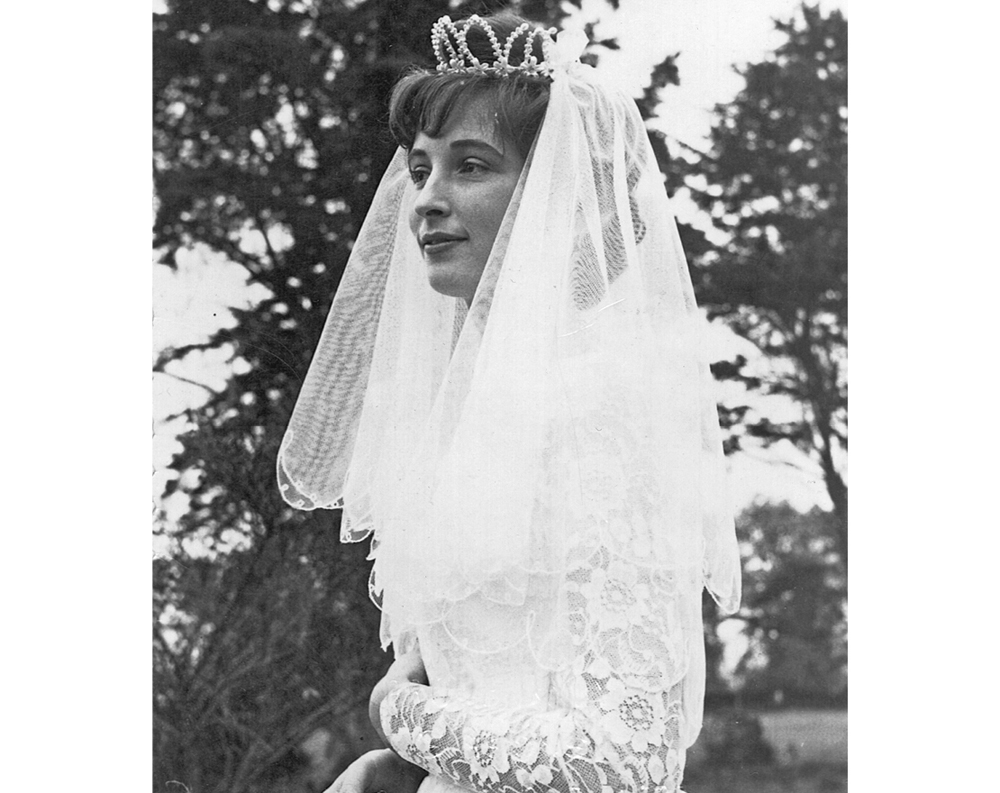

In the meantime, a shy girl was begotten and born to William and Lizzy. When she turned fifteen William would depart, his time-bomb heart tick-tocking him into the Great Unknown. And Lizzy would out-linger, though her brain would depart on the early train to beyond, long before her body would follow. She, clad in shoes, a skirt and a blouse beneath a cross-your-heart, Father Son Holy Spirit, bra.

Jean (for that was the young maiden’s name) was beautifully unaware of her growing beauty, gap-toothed and lost as she was in the cloud of testosterone she and her three sisters predominantly inhaled.

6 hungry boys + 4 potatoes each makes 7 million peelings old …

‘What happened to your hands, Nanna?’

‘I put them in the fire, Caroline.’

‘Did you put your face in the fire, too?’

… and only the girls paying keep … Well I think I’ll just go and boil a head of lettuce and get it over with. Inhalations were deeper on McSwiney Street than elsewhere, and exhalations late.

You see, when God looked up from Jean’s incisors, he got transfixed by her eyes and He threw in an infinity of love. Teeth could only mull over this wonder while enjoying a cocktail stick. But they, hard as they were, could never know this love.

Love me just a little bit and I’ll cast such love on you, but I won’t smile in photos. That’s something I won’t do.

She wore a pink dress with the velvet dusk of the Irish rose and led love into a ballroom wherein she was tricked into a dance with a charming rebel. Her jilted girlfriend left, thinking she may have in fact won, and her mouth saying, on receipt of the news from her up-down eyes:

‘He has a very good-looking face but he is a bit short in the leg.’

But Jean thought that the way this beautiful man-face was looking at her more than made up for the deficit in the leg. And so they courted, he picking her up in his racing green Fiat 500 and stopping not far from McSwiney Street where they kissed and she told him that she loved his face.

‘So do ye think ye might marry me someday?’ he said, and she laughed at the irony of the man with all the words, having so few.

‘Shelling Hill’ by Gerry Corr

You’d be blessed to find it; down tortuous track

Hardly the breadth of Cooley’s fabled hero,

Not to mention Maeve’s brown bull.

From the beginning it was our private place

Our little car, almost without bidding,

Bringing us there each Sunday

One day a cow came by,

Drawn not by the scent of forbidden fruit

But by blameless apple,

Mooing an end to our caresses

Passion and laughter not a good mix.

Poor bedfellows, you might say.

We laughed again on another day

When words unbidden dropped in on us

‘Do you think you might marry me one day?’

I swear a passing dog smiled,

The ocean roared, of course,

And the Lord of sky beamed a blessing.

My lady trembled a little

As in girlish excitement

Until a giggle breached it’s frantic confine

And we took refuge in each other’s arms.

‘Who said that?’ I said, and we laughed

And laughed, and laughed.

Cupid’s cheeky chariot joined in later

Rocking and rolling us

Home to Dundalk …

22 February 2000

And all would be content ever after but for Gerry having a penchant for revealing the gap teeth.

He thought that if God, when pouring in lashings of love, had not mixed in equal measures of hope and fear, then it might not have been so delicious to go to such wicked measures. But then again, if easily won, would it have been so rewarding?

Years passed as they do in Grimm fairytales. Jean’s tummy grew and grew, again and again and again, and out came Jim Gerard Sharon Caroline and Andrea. A family band.

‘This is PG’ Grimm thought for the very first time, and hoped they’d forget the second boy Gerard. And so …

Hope, Fear and the Beetroot

One day a guttural and terrifying scream did interrupt the fledglings at their various offices above and had them racing down the stairs to see …

… their father doubled over by the open door of the fridge, coughing into a pool of blood! With mouths open and poised to join their petrified mother in this primitive and tribal chorus, they observed that the cough had morphed into a laugh … For one could not miss opportunities when they presented themselves so beautifully, he thought … We don’t cry over spilled milk … but poor Mammy does … All over the spilled juice from a jar of pickled beetroot.

Baa.

Sorry, Jean.

The Cross Pen

It must be acknowledged that the father, though terribly cuddly, was betimes a grumpy daddy.

‘You’re in a bad mood again, Daddy.’

‘I AM NOT IN A BAD MOOD!!!’

Various sounds and head-jerks alerted us to his internal weather system. Grumbles and groans, muted thunder and bolts, and the head jolting twice, three times to the left with the assumed objective of loosening an invisible suffocating collar and tie. Or a noose, perhaps.

He appeared home from work this day with the aspect of a man whose inner sky has clouded over an oppressive grey.

‘Have any of you seen my Cross pen?’

One can only imagine now the afflicted individual who, on opening his bag at work earlier, discovered to his chagrin the aforesaid missing biro. And therein the brew began …

‘No, Daddy.’

And so it was daily for approximately eight bewildered days, with the question gathering variants in meaning and expression, such as:

‘Did any of you take my Cross pen?’

And punctuated with ‘Ach’s’ galore.

‘Ach!’

On perhaps the sixth day I had found myself deeply fatigued with the Cross pen, so I decided to say:

‘No, I haven’t seen your Cross pen,’ just when he had begun the refrain, ‘Did any o—’

‘No.’

On the eighth day we duetted again, according to the scripture, except this was different.

‘Lo, what’s this?’ I remarked to myself. ‘My longest exhausted noooooooooooooo has failed to put an end to today’s song?’

‘Everyone, I want you to check your school bags for my Cross pen.’

‘Tssk, Daddy, it’s not in my school bag! I didn’t take your stupid [inner voice … as that, I am not] Cross pen!’

‘Just check it, Andrea.’ (Weather warning: Pandy when cuddly, Andrea when not.)

So poor wee me drags my school bag in with my own weather. My ochs and huffs and blows and I start to pull stuff out of my bag. I really am above all this carry-on now, when … wait … what is that shine of silver peeping out of Bran, my riveting reading book?

Oh …

I just could not understand it. I ran off crying.

‘I still feel bad about that one, Pandy. That one took a while.’

Baa.

Inherited Wickedness

And so we did it too, to each other, and admittedly I fear I was the worst because:

‘You’re boring me now, Andrea,’ was as regular as the Angelus.

Oh, the Angelus always makes me think funny thoughts. You know the visual montage they play on the TV to the sound of the dong-dongs? Random people in various jobs putting down tools, if they have any, and pausing to reflect on God (as ye do at six o’clock every day)?

The farmer turning off the tractor, looking up to the right at … I presume God, but we don’t actually see Him (oh that’s something to reflect on right there … it’s working!).

The mammy (there she is again) resting on her hoover to look out the window at the tweety birds circling … (or are they above her head, haha).

Nature, nature, glorious nature. It’s everywhere!

Babbling brooks, migrating swallows, potatoes being picked with earthy, black, return-of-the-native nails.

And when Ireland recognised that God loves all his children and got the chance to see many of them in real life (long live the one hundred thousand welcomes, and when faced with this chance to give thanks, may we never forget the céad mile fáiltes a million of our own starving refugees needed), as Ireland grew and changed, so too did the montage …

Now we have a Chinese lady looking up from her office desk (killed two isms with the one stone there) and I’m not even on the funny thoughts yet but you have them too, don’t you?

The man pausing his unrolling of the toilet roll to look up and ponder …

What are you supposed to do if the Angelus strikes then, tell me?

Eh, hold on a second now, God.

(He made me like this … God, I mean.

Hi, have I been introduced yet? No – ye left me out, of course ye did.

I’m Guilt.)

… Toes mid-curl at bottom of dishevelled, silken and moving, two-headed monster.

Baa.

Sorry, God.

Ahhhh! Air traffic control!!

Hmm. For some, the pause for the Angelus should most definitely not be observed.

‘Ellis Island’

On the second Sunday

Annie be my guide

Liberty’s a welcome

To an aching eye

We’ll grow up together

Far away from home

Crossed the sea and ocean

To the land of hope

Kingstown to Liverpool

Crossing the Irish Sea

You gotta keep your wits on you

Where you lay your head

Six minute medical

Leaving no chalk on me

Goodbye Ellis Island

Hello land of free

Every man and woman

Every boy and girl

Sing out Ellis Island

Sing a song of hope

Sing for us together

Sing we’re not alone

Sing we’ll go back someday

Sing we will belong

When the leaves are falling

And the sky is on the ground

We will come together

And sing of Ireland

Thanking Ellis Island

Thank you USA

You gave us a home here

Crying a brand new day

Queenstown to New York Bay

Wild Atlantic Ocean

You gotta keep your wits on you

Where you lay your head

Six minute medical

Leaving no chalk on me

Goodbye Ellis Island

Hello land of free …

Did they really do it to me, though?

If I’m honest, my only memorable humiliation was thinking we were all still playing hide-and-seek when they’d forgotten me, a thumb-sucking curl that Jim had manoeuvred into the top of the hot press … Ahhh, cradled in winter smells … Yum yum.

They didn’t even pronounce me missing.

I was likely found following another ‘Where’s Pandy?’

Thank you, Mammy.

But I had a nose for under your skin that wasn’t natural in a child.

Poor Mammy, she must have been going through the Change (distant screaming far off), because she screamed at every little thing.

‘Ahhhh!!!!’ was to be heard at regular intervals, and a few petrified, hair-raising:

‘Gerry!!!!!!’s

‘Ahhhhhhhhhh!!!!!!’

‘Gerry!!!!!!’ … I’m actually doing it again …

… I’d fall down on the ground and writhe in agony for her …

‘Gerry!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!’

‘Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh-hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!!!’ Fighting the invisible bogeymen away from my twisting, turning, don’t-touch-me! head …

‘Nooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo!!!!!’

What could it be? I needed to be prepared for all eventualities …

So what if it was just that she saw Caroline’s scrambled egg pot from earlier still sitting yellow and curdled in the sink … She’d told the bitch to CLEAN IT NOW fifteen minutes ago. But to me, then, life was like a disowned rucksack in a train station … You never know.

Baa.

Sorry, Mammy.

Comeuppance imminent, Pandy

And Jim was … How can I put it? Addictive. Yes, that’s it.

He was packing shelves in Tesco, on parole for not sitting his Leaving Cert. You see, he actually stood it up.

(I’d tripped over his school bag too many times, on my way to Paul’s, to not understand what they were roaring about inside. And to understand why he was grounded. Then I worked out that the grounding must be elsewhere because we can’t find Jim in his room and a window is open.)

And he had a TASCAM 244 studio in his purple bedroom with all of the manuals just waiting for him to feast on and get to know intimately.

It was a very difficult time. The artist’s Tesco blue period, I could say.

I honestly can hear a violin!

Oh, forget it. That’s just Sharon in her room.

How embarrassing.

Jim was ‘not in a good place right now’, as they say, and every day he awoke to find his nightmare was reality.

Now I love everyone here, you know that? It’s just a twitch.

I’m just as God made me.

Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh …

There was a hand gesture (no, not what you’re thinking, but).

A hand gesture, unique. (If you have interactive, press red now.)

It didn’t have sound, mostly; for mostly, it didn’t need it. And you wouldn’t want to be relying on that, when sometimes he is already on his way, in his prison blue overall, to pack the shelves (Andrex Quilted today) and he thinks it’s over and that he has won and that I couldn’t possibly be at the window now … but look!

I’m there.

I start with a serene, otherworldly smile, as if one has passed but is at peace. I am sublime and I am prophetic.

And then one discerns a subtle hand gesture emerging from my sleeve. A gesture that wouldn’t make sense to most and was a method of tortuous teasing unique to us. Like the ghost of the bird that is cupped in one’s hand, being ever so gently rocked to sleep. And then my face, all sad, ever so sad, like it’s a raindropped window through to the deep compassion and pity for my poor brother that was filling my very being …

Baa.

Sorry, Jim.

Oh, I think I have to stop now … This is turning into confession.

Oh no … Don’t think about it … no.

Bless me, reader, for I have …

I am back in Dundalk, that choppy-haired, blood-lipped, slip, red bra and Doc Marten boots time, and (though you didn’t know it … or is that what I did to make you love me?) … I was troubled. The pain of a pop star … you’re breaking my heart.

Bosom, when she refers to it, says things like:

‘Do you remember the time you drank tea, Bosom?’

Mammy must have been really worried because she came into the front room, stole my teapot, replaced it with a bottle of wine and practically locked us in.

Anyway, it’s like my ears are on inside out and I’m so sick of myself that I rarely see, but the times that I do see, I take for a sign. For instance …

I raise my coal worn eyes from my feet and realise they have opened on the Friary Church and I think I must go in … I am supposed to go in. And then lo and behold, I just happen to sit in the pew queue for confession … So …

I’m in.

The dragging wood and my heartbeat reveals the spectre behind the grid. Bowed, white-furred head, not looking, but I’m looking and I feel just awful about having to say – to lie! – ‘It’s been three years, Father.’

And before he could get the most gentle ‘Why, my child?’ out of his still-quivering-in-the-wake-of-so-many-prayers lips, I blamed him for the whole lot of it. (God … was I going through the Change?)

‘I find it difficult, Father, as a woman [I had to verify that coz even if he was looking, it would still be hard to tell] to hold my head up high in this church.’

‘Oh no,’ he said.

Yes I do. My grandmother Alice was preached at to bear all the children God thought fit to bless her with … She had number ten at the ripe young age of forty-seven and if there was a break of more than a year between children, which apparently in Alice’s story there was not, a mortified woman could be asked why she was not bringing more baby Catholics into the world and was everything all right at home, so to speak.

But back to Alice (who would later take to her bed for two years, and who needed electric shock treatment to jolt the bloodless depression out of her, once and for all) … Not once did Daddy see her sit at the table with them and eat the food she had made. She waited. A benevolent and loving servant. A womb with no view.

I wish I could read your memoirs, Alice … I want to hear of some blessed sunshine days … There must have been some? Episodes of light beyond the low-hanging dusty grey of the honeymoon you spent cleaning Corr’s Grocery before it opened in Dundalk. And the extraordinary sign-off in the postcard from James Corr, your then betrothed:

Lough Derg, 1926

Dear Alice