Полная версия

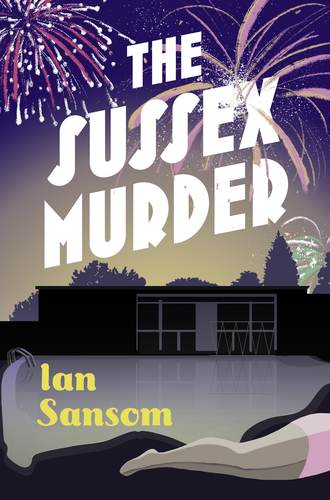

Flaming Sussex

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

Copyright © Ian Sansom 2019

Cover design by Jo Walker

Ian Sansom asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008207359

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008207366

Version: 2019-04-11

Dedication

For Ciaran

Epigraph

God gives all men all earth to love,

But since man’s heart is small,

Ordains for each one spot shall prove

Beloved over all.

Each to his choice, and I rejoice

The lot has fallen to me

In a fair ground – in a fair ground –

Yea, Sussex by the sea!

RUDYARD KIPLING

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Footnote

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Ian Sansom

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

LEWES, SUSSEX, FRIDAY, 5 November 1937.

At about four o’clock, Miss Lizzie Walter, a teacher at the King’s Road Primary School, said goodbye to her young pupils. The children clattered out into the dark streets of the town, preparing for the night’s revelries – and Miss Lizzie Walter was never seen alive again.

Lizzie lived with her parents, respectable working-class folk, at 11 Saddle Street. Her father was a tradesman, her mother a housewife. She was young, intelligent, hard-working, good-looking. She liked literature, music and art. She was dressed that day in a double-breasted brown tweed coat, but wore no hat.

It is about a twenty-minute walk from King’s Road School to Saddle Street and normally Lizzie would have returned home by four thirty, but because of the Bonfire Night preparations her mother and father felt no anxiety regarding her failure to return. Bonfire Night in Lewes is a famous night of revelry. They assumed that she had met friends and gone to join the celebrations.

It was not until six o’clock the following morning, when they discovered her bed had not been slept in, that her parents raised the alarm – and shortly after when I found Lizzie’s body floating in the lido at Pells Pool.

We had, at that point, been in Sussex for less than twenty-four hours.

CHAPTER 2

OF ALL OUR TRIPS AND TOURS during those years, our trip to Sussex was one of the darkest and most difficult: it was a turning point. We arrived, as always, intent on doing good and reporting on the good: we were, as so often, on a quest. We departed less than heroes. None of us could hold our heads up high.

The County Guides series of guidebooks, as some readers will doubtless be aware, but others may now well have forgotten, were intended by their once world-famous progenitor and my erstwhile employer, Swanton Morley, as a celebration of all that is good in England, volume after volume after volume of guides to the English counties, celebrating their variety and uniqueness. The County Guides – in their smart green uniform editions, at one time as familiar as the Bible or the old Odhams Encyclopaedia on the shelves of the aspirant working and middle classes – were hymns to the noble spirit of Britain. They were intended as uplifting literature – ‘up lit’ was the term coined by Morley in an interview in the short-lived Progress magazine in June 1939: ‘What this nation needs now is up lit.’

In reality, in every county we travelled to in those long years together, researching and writing the books, we seemed to encounter the very worst of human nature: downbeat doesn’t do it justice. Downcast, downfaced, downthrown and downright.

In Norfolk it was treachery, in Devon it was devilry, in Westmorland tragedy and in Essex farce, but in Sussex we encountered not only murder but mayhem and depravity: it was not just the burning of the crosses and the flaming tar barrels, the torchlit processions, the sheer anarchy of Bonfire Night in Lewes, it was the revelation to ourselves and to each other of our own terrible inadequacies. For ever after, Morley referred to The County Guides: Sussex as ‘flaming’ Sussex. (He had pet names for all the books, in fact: The County Guides: Essex was always Essex Poison to him, Westmorland was Westmorland Alone, Cheshire Rogue Cheshire, and etcetera and etcetera).1

Before we arrived in Sussex, Morley, as usual, had drawn up a long list of what to see, with an even longer list of annotations. Having already produced our County Guides to Norfolk, Devon, Westmorland and Essex we had begun to develop a kind of routine. We would meet either in London or at Morley’s vast and eccentric estate in Norfolk, St George’s, where he would brief me and Miriam, his daughter, and we would then embark upon our adventure in his beloved Lagonda, Miriam at the wheel, Morley strapped in behind his typewriter, and me as general factotum.

For our journey to Sussex, Morley’s list began with Abbotsford Gardens (‘Open to the public on weekdays only, alas, but fabulous aviaries – and monkeys! – and light refreshments!’) and included, in addition to all those Sussex places one might reasonably expect to find in any good guidebook and gazetteer, many places that one might reasonably not, such as the Balcombe Viaduct (‘A marvel of Victorian engineering!’), the Pavilion in Bexhill (‘A marvel of modern engineering!’), the Rising Sun Inn at North Bersted (‘The Jubilee Stamp Room: one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. A whole room papered from floor to ceiling with postage stamps, said to number in excess of three million’), the Chattri (‘War memorial erected by the India Office and the Corporation of Brighton to commemorate the brave Hindu and Sikh soldiers who died in the Great War’), Chick Hill (‘Marvellous view to France’), Clapham Wood (‘Satanic mists, apparently!’), Climping (‘We must visit the Moynes!’), Frant (‘Lovely obelisk’), the Heritage Craft School near Chailey (‘The salvation home for cripples!’), some Knucker Holes (‘Bottomless, some of them, reputedly’), Mick Mills’ Race (‘Wonderful avenue in St Leonard’s Forest where the smuggler Mick Mills raced the devil and won’), Shoreham Beach (‘For the railway carriage homes, of course! England’s Little Hollywood!’) and the Witterings, for no good reason, both East and West.

I’ll be honest, I had absolutely no interest in Sussex.

The truth was, I shouldn’t even have been in Sussex.

Before we arrived in Sussex, I had decided to resign.

I had at that time worked for Morley for a period of exactly four months. This was late in 1937, after my return from Spain, where I had discovered, to my horror, the horrors of war. Perhaps I should have known better: now at least I knew the worst. Adrift in London, I had answered an advertisement in The Times and had found myself apprenticed to the most famous, the most popular – and certainly the most prolific – writer in England. During those four intense, turbulent months, Morley had somehow produced four books – Norfolk, Devon, Westmorland and Essex – in addition to his usual output of articles and opinion pieces on everything from the care of houseplants for the Lady’s Companion, to the etymology and usage of strange, obscure and pretty much useless words in John O’London’s Weekly, to endless wearying tales of moral uplift and derring-do for anyone who would have them, including the Catholic Extension, the Christian Observer and many and various – and thankfully now defunct – earnest freethinking journals.

As his assistant, it was my job not just to sharpen Morley’s pencils – though pencil-sharpening, pen-procuring, inkwell-filling, notebook-filing and all manner of other stationery-related activities were indeed a large part of my daily activities – but also to help him and Miriam correct proofs, take photographs, deal with correspondence, pack and prepare for our long journeyings round the country, and to perform all other duties as necessary and as arising, including providing physical protection, offering what would now probably be described as ‘emotional’ support and encouragement, and of course listening to what one biographer – borrowing a phrase, I believe, from Gilbert and Sullivan – memorably described as Morley’s ‘elegant outpouring of the lion a-roaring’, but which I might describe as his endless, pointless, glorious ramble.

While Morley was working on the proofs for Essex, I had been tasked with putting the finishing touches – ‘Semi-gloss ’em, Sefton, but semi-gloss only, please, we don’t want too much of your smooth and lyrical, thank you’ – to a number of articles, including something on ‘The Nature and Management of Children’, about which I knew precisely nothing; another titled, depressingly, ‘Conversations with Vegetables’; and another about the sound of tarmac for an American magazine that called itself Common Sense but which displayed no sign whatsoever of possessing such and which paid Morley vast sums for articles on subjects so strange that Miriam liked to joke that the magazine might usefully change its name to Complete and Utter Nonsense. (‘The Sound of Tarmac’, for example, was intended as a companion piece to two inexplicably popular articles we’d produced for the magazine, one on the quality of modern British kerbstones and another on regional, national and international variations in the size of flagstones. The Yanks couldn’t get enough of this sort of stuff.) My most recent work, gussying up one of Morley’s quick opinion pieces – eight hundred words for a magazine with the unfortunate title of the Cripple, a publication aimed at war veterans and the disabled, in praise of Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help, all about the importance of self-discipline in overcoming difficulties and achieving happiness – had left me feeling not so much self-helped as self-disgusted, as if I had drunk water from a sewer or a poisoned well.

Four months in, I was physically exhausted, I was enervated.

And I was envious.

At college I had naively believed that I was the master of my own destiny; in Spain, I had realised that none of us truly determines our fate; and now I was beginning to think that my entire life was a matter of complete insignificance. The real problem was that the longer I worked for Morley – a true literary lion, a working-class hero, an international figure who was big in Japan and who counted the Queen of Italy among his fans, and indeed frequent correspondents, a man who had pulled himself up by his own bootstraps and who had then set about pulling up the bootstraps of the nation – the more I worked for this infernal writing machine, this actual living and breathing – there is no other word for it – genius, the more I was reminded of my own lack of drive and determination and brilliance and the more I came to despair of the possibility of ever making a significant contribution to the world of letters myself. I had long harboured dreams of becoming a writer, yet the only writing I did for myself now was the occasional postcard, my betting slips and IOUs. Writing for Morley, a master of the English language, I had become thoroughly disgusted with words. His facility both fascinated and appalled me. His achievements seemed incredible – and worthless. The last poem I had written consisted of exactly four words: ‘Vexed ears/ Wasted years.’ The County Guides were crushing me. I was beginning to feel no better than a broken, beaten dog.

My only consolation was that between books I was able to return to London, where I would enjoy all the things that city has to offer and would attempt to iron out the various knots and kinks that had formed in my mind and my body by consorting with the kind of people who had knots and kinks of their own to deal with – my kind of people.

Which is how I had ended up, on a Saturday night at the very end of October 1937, at the all-night vapour bath on Brick Lane in the East End.

CHAPTER 3

IT WAS EXACTLY WHAT I NEEDED. Frankly, if you can’t get exactly what you need in the East End on a Saturday night, there must be something wrong with you – something seriously wrong with you.

After the relaxation and rigours of the vapour bath, I had adjourned to a pub nearby for light refreshments and to enjoy the company of people who certainly looked like, but who may or may not have been, thieves, prostitutes and ponces. One should never judge by appearances, of course, according to Morley. One should be open-minded. One should take people as you find them. The only problem is, when you take people as you find them, you’ll often find that they’ll already have taken you – in every sense – for everything. After a couple of hours of drinking and singing around the piano, I somehow found myself taking up the generous offer of hospitality and a bed for the night by a sharp-suited Limehouse chap I’d never met before and a couple of his lovely female companions. I did not judge them by appearances, being entirely incapable of doing so – and it turned out, alas, contra-Morley, that this sharp-suited individual with his female companions was indeed a ponce with his prostitutes, but I was determined I was not going to allow them to prove themselves also as thieves.

I awoke early after our long and largely sleepless night, having eventually fallen into an unsettling dream in which I was sitting with a man at a large glass table, drinking champagne, him wearing a silk suit and brightly polished shoes, and with a set of scales before him and saying he had a special present for me. At least, I think it was a dream. What woke me was the sound of birds.

At St George’s, in the cottage that Morley had provided for me in the grounds of the estate, I would often wake to the sound of birdsong. All else there was silence, though if you listened carefully you could hear not only the sound of water bubbling and swirling in the faraway streams and in the cottage well, you could actually hear your blood coursing through your veins. It was unsettling, the country.

But in London: birdsong?

I remember being momentarily confused. I lay gazing at a crack in the ceiling above me, through which it would have been possible to insert my fist.

Was that the sound of birds?

Was I in Norfolk?

Or was I back in Spain?

Was I dreaming?

It was definitely the sound of birds. Lots of birds.

Out of the corner of my eye I could see empty beer bottles and cigarette butts piled in a saucer. The place, wherever it was, seemed dirty and unloved. I raised myself up on my elbow. There was a woman lying asleep beside me.

And then I remembered.

It had been a very long night.

I turned my head. My clothes lay discarded on the floor. The Limehouse chap and another woman lay sleeping in a bed opposite. There was a lighted cigarette smouldering in an ashtray on an upturned case by the bed, and what looked like a fresh glass of whisky perched precariously next to it.

I took some deep breaths and then coughed quietly in order to gauge any response.

Nothing.

Having thus determined to my satisfaction that my new friends were either fast asleep or at least innocently dozing, I rose quickly and quietly, intent on hanging on to whatever remained of my dignity and in my wallet, gathered up my clothes and fled from the room, down a dark stairway and along a corridor towards a door.

It was precisely at that moment, cold and ashamed, and the previous evening’s activities returning clearly to my mind, that I determined that I should no longer live my life as a slave to my whims and desires, or indeed as a slave to the whims and desires of others, but that I should once again attempt to master myself and my destiny. It was then that I determined that I had had enough of being used by life, by London, and by everyone. Morley believed that on our grand tour we were surveying one of the great wonders of the world – Great Britain – and London of course, as it always has, believed it was the great city in this Great Britain, but at that time, in those years, it felt nothing like great and I felt nothing but forever lost and losing, a man condemned to life on a slowly sinking ship.

Stumbling as I reached the door, I thought I heard movement from my companions up above, and so fled from this latest prison of my temporary lodgings with new resolve – and into a scene of utter chaos.

CHAPTER 4

IT WAS THE SOUND OF BIRDS, and it was the sound as much as the sight that struck me, a cacophony of whistles and trills, accompanied by the bass-soprano of the voices of men and women, and the deeply disturbing sound of whimpering animals.

‘Pretty foreign birds! Pretty foreign birds!’

Out on the street, as far as the eye could see, piled one upon the other, there were cages full of birds: larks, thrushes, canaries, pigeons and parrots. There were also dogs and cats in boxes, and chickens and snakes and gerbils and guinea pigs and weasels and tortoises, and goodness knows what else, animals of every kind everywhere. Here, a new-born litter of puppies tumbling over each other in a child’s cot being used as a makeshift pen. There, a raggedy black rooster peering out of an old laundry basket. And endlessly, everywhere you looked, there were bulldogs and boxers and pit bulls straining at their leashes, restrained by men who looked like bulldogs, boxers and pit bulls straining at their leashes. It was a Noah’s Ark, with flat caps and cobbles.

I’d forgotten about the market.

On Sundays, in those days, the centre of London shifted; it went east to Bethnal Green and its environs, from the junction with Bethnal Green Road and Shoreditch High Street, onto Sclater Street and Chance Street and Cheshire Street: here, on Sundays, you could buy and sell just about anything. Petticoat Lane, down by Aldgate, became the people’s Piccadilly, the mecca for cheap, cheerful and ‘unofficial’ goods: on Sundays, the East End became the dirty, cracked dark mirror of the West.

And here I was, in the midst of it, Club Row Market – the place where the working men and women of London came for their animals. A nightmare of containment and enclosure.

As I shut the door behind me and entered the chaos, I remember looking up and noting that opposite, across the road, there was a wet fish shop with the traditional, unnecessary sign outside, ‘Fresh Fish Sold Here’. (This sort of signage was one of Morley’s many bugbears, addressed in one of his popular, hectoring Some Dos and Don’ts pamphlets, Shop Signage: Some Dos and Don’ts. ‘We know it’s “Here”, because it’s here, we know it is being “Sold” because it is a shop, and if not “Fresh”, then, frankly, what? So “Fish”, in short, for a fish shop, will suffice.’) A man in a white apron stood outside the ‘Fish’ shop, scooping jet-black, chopped, gelatinous jellied eels into white enamel bowls: the mere sight of it made me want to retch; I had to struggle to contain myself. Pausing mid-scoop, as if having sensed my dis-ease, the man in the apron looked across at me and scowled in disapproval. Gagging rather, I glanced away to see standing directly in front of me an elderly gentleman in a fez selling hot roasted nuts from a pan heated over a metal drum of embers set upon a simple wooden trolley. I could feel the heat on my skin. This man too looked directly at me and shook his head, acknowledging and also somehow regretting my very presence.

Which was when I realised I was naked.

Fortunately there were so many people jamming the street – it could have been a medieval fair, or a football crowd – that no one paid much attention as I huddled in the doorway and frantically pulled on my trousers, shirt, jacket and shoes. The problem was not that I was getting dressed, but that I was getting in people’s way.