Полная версия

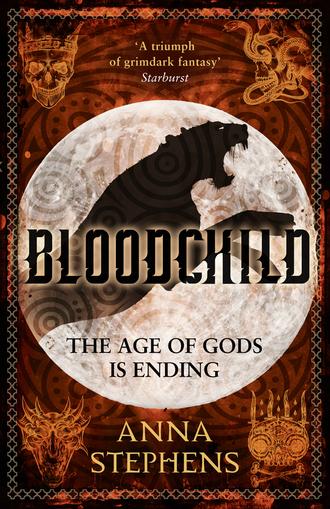

Bloodchild

Her face twisted with bitterness. She turned on her heel and stalked across the drill yard. When Dalli called after her, tentative and too quiet, it was easy to pretend she hadn’t heard, to pretend there were no tears clogging her throat. She wouldn’t cry for Dalli’s spite. Rillirin stalked up the southern watchtower’s steps and out on to the allure, staring into the night. Krike was out there somewhere and for a mad, intoxicating moment, she thought about slipping out of the fort and crossing the border, losing herself in a foreign land and never coming back.

There was a fluttering in her stomach, a weird shifting. Rillirin leant her spear against the wall and put her palms on the small mound. Is that you in there, little warrior? Is that you? Do you want to go to Krike? Nothing. Or do you want to stay in Rilpor? Another flutter.

Rillirin huffed. ‘All right then,’ she muttered to the first stars and the stirring life within her, ‘that’ll do. Rilpor it is. But if we’re staying, I really hope we win.’

‘Colonel Thatcher?’ Rillirin hurried to catch up as the officer crossed towards the mess. He paused and waited, giving her a distracted smile. ‘Colonel, I’d like to volunteer.’

He glanced sidelong at her spear. Despite general Rilporian attitudes to women fighting, her status as a sort-of-Wolf had guaranteed her a weapon when she and Gilda made it to the forts. ‘Volunteer for what?’ he asked.

‘Anything, really,’ she said. ‘Anything that gets me out of the forts. Or a transfer to one of the others.’

He paused by the mess hall door. ‘Transfer? I know we’re tightly packed in here, but the other forts are just as crowded.’

‘Away from the Wolves,’ she said in a rush. ‘I’ll go when the civilians go, so it won’t be for long, but I’d like to help out. Riding patrols, perhaps?’

He gestured her into the mess and followed and they joined a line of people waiting for breakfast. ‘You’re pregnant, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, but I can still ride and fight and scout,’ Rillirin said, annoyed at how everyone assumed she was incapable. ‘I’m barely even showing,’ she added.

Thatcher frowned. ‘Pregnant women get extra rations,’ he said and pointed at the soldier doling out bread and porridge. Rillirin blushed, stammered an apology. ‘As for volunteering or moving barracks, let me see what I can do. Ride and scout and hunt, you say?’

‘Well, I’ve done it before a few times,’ she admitted and took the bowl offered, added a spoonful of honey. ‘I want – I need – to be useful. I can’t just sit here doing nothing.’

‘I appreciate your enthusiasm, but I need experienced people performing those tasks – the security and provision of the forts isn’t something I can trust to a novice. But I’ll sign you up to train with the militia, and we might get you out on a foraging party or something. There are lists of things that need doing, if you don’t mind hard work.’

‘I don’t mind,’ she said. ‘I just need to be busy.’ He nodded, already distracted by another soldier waving a sheaf of papers, and slipped away into the press. Rillirin examined the long trestle tables packed with soldiers and civilians. A knot of Wolves eyed her from a corner; Isbet beckoned with a wave.

Rillirin took her bowl outside and ate in the early sunlight. Two hours later, she joined three hundred civilians in the drill yard and began to learn to fight like a Ranker. In the afternoon she rode out with a firewood party, and by nightfall she’d been transferred to Fort Three.

It was exactly what she wanted, so it had to be the pregnancy that made her cry herself to sleep.

TARA

Seventh moon, first year of the reign of King Corvus

Marketplace, First Circle, Rilporin, Wheat Lands

Tara didn’t know what to think of the shopping list Valan had given her, didn’t want to examine what it said about the man who owned her, who lived a life of brutality and violence, who only three days before had flogged one of his other slaves for breaking a plate.

The very first of the Rilporian merchants had arrived, those bastards who didn’t care who they sold to or what it was if it turned a profit. The same merchants who sold opium to the rich or the desperate, or stolen goods to the unsuspecting poor, had arrived in a small, wary group outside the gates and Corvus had allowed them entry.

Tara had to admire their ingenuity even as she cursed their greed. Livestock and grain, jewellery and weapons, fish and information: all were for sale. Some merchants were even accepting slaves as payment and then bartering those for more goods and reselling on again, a loop of wealth that gained them a few copper knights more with each transaction.

She stared at their bare necks with hungry intensity. Rilporians without slave collars – how was it they were allowed to walk free? She stopped at a stall holding thin bolts of cloth, all of them dyed an uneven blue. The quality was poor, but the price was high and it was the only stall selling material in the required colour.

‘How much for eight yards?’ she asked.

The man leered at her, brown teeth in a pockmarked face. ‘For you, pretty? Depends on what you got to offer. Knock a bit off the price if you’re a good girl.’

‘I’m not a good girl,’ Tara said and then cursed as the merchant winked and leered some more. ‘No, is what I’m saying. How much?’

‘No? Say no to your owner too, do you? Bet you don’t. How’d it be if I told him you offered yourself to me in exchange for your freedom, eh? How’d that be?’

Tara rounded the stall and grabbed the man by the front of his shirt, hauled him close until they were nose to nose and she was enveloped in the stink of his breath. ‘How’d it be if I choked you to death with your own shitty linen, you traitorous little wank-stain? I want eight yards and I want a good price.’

‘Royal a yard, royal a yard and no less,’ the man croaked.

Tara shoved him away. ‘I’m not paying you eight silvers. I wouldn’t pay two silvers for this quality of dye.’

The merchant spat at her. ‘Fucking Mireces can afford it, why shouldn’t I make a profit serving scum like that?’

Tara could’ve told him why not, could’ve mentioned the fact many of the slaves here in the market would be beaten, starved or executed either for failing to purchase the goods or for buying at too high a price. She knew none of that would matter to this man.

She put her back to him and snatched up the tailoring shears, started measuring the linen. When he tried to stop her she shoved the shears towards his face and he fell back squealing, though not loudly enough to attract attention.

Tara hacked off eight yards and threw two silver royals on to the table. ‘And just so we’re clear,’ she snarled in his face. ‘You’re all scum.’ She stalked away before he could reply and made it twenty yards before she remembered to drop her head and slow her steps, kill the fire in her eyes.

A slave was watching her, standing with a couple of others. A big man, huge in fact, with a beard halfway down his chest. He had a trowel in his hand and was supposed to be shovelling mortar on to the inner face of the wall, right about where it had breached. Where Durdil had died. She blinked and looked away, looked back. The man went to wipe his face, then tapped his fingertips quickly against his heart. Tara faltered, then kept walking. When she was almost past she glanced back, gave him the tiniest nod. A Mireces overseer snapped something at him and he bent to his task again.

A mason. That could be useful, either to bring the wall down or to blow the fucker up, maybe. Somehow. Failing that, he’s as big as an ox and if he had a shield he could hold a stairwell indefinitely.

It wasn’t much, but it was a start. Tara checked her list and bought those items she could find. Combs and hair ribbons; four fine cups and plates with a matching pattern of flowers around the edges; linens and breast band, linens for children. The underwear was the only thing she got for a good price, there not being any free women or children in the city who might need such things. So cheap, in fact, that Tara took the enormous risk of buying fresh ones for herself and then, on a whim that could see her executed, she bought two painted wooden horses.

The slave woman who was selling them wept with silent hopelessness as she handed them over. ‘Your children’s?’ Tara whispered as she paid. The woman nodded; then she looked fearfully over her shoulder at the Raiders crouched in a circle and betting on dice.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Tara said. ‘Have they gone to the Light?’

‘I don’t know,’ the woman choked. ‘I lost them in the smoke. I let go of their hands and they were gone, taken in a heartbeat. I lost them.’ Her voice began to rise and Tara shushed her, but it was no good. One of the Raiders looked up, scowling, and Tara did the only thing she could: she shoved the toys into her basket and walked away. She wasn’t even around the corner before the screaming started.

As King’s Second, Valan occupied the large suite of rooms formerly belonging to the dead Prince Janis. Familiar with the palace’s layout from the siege, Tara knew exactly which corridors and shortcuts led from the suite to the king’s chambers. Handy, for when the time came, and the brief moment with the mason today gave her hope it would be soon. Getting the Rankers on side was easy enough, but they needed every slave rebelling at once, rising in every Circle and every district and causing so much chaos that no one would notice her slipping through the palace and putting a knife in Corvus’s heart before drowning Lanta in her own filthy, sacrilegious godpool.

If only it could happen now. Tara didn’t do regret as a rule, but right now she was regretting buying those wooden horses with rare intensity. It had taken hard work and luck and the exact right mixture of defiance, ability and humility to charm Valan, but it could all come crashing down around her if he took exception to her decision-making.

Tara had laid out the purchases on the big table in Valan’s suite and moved to her place by the door to await his return, when she’d have the honour of taking his weapons and boots and presenting him with wine and food. She got to remove his armour and then pour his bath, a luxury he couldn’t get enough of down here in the warm lands.

So fucking honoured.

She also got to tell him about any infractions by the other slaves during his absence, what the kitchens had prepared for him, and any messages that had arrived while he’d waited on the king. She tried to convince herself it was the same as being Mace’s adjutant back before the world had gone to shit, but then Mace had never insisted she scrub his back while he sat bollock-naked in a bathtub. She shuddered and reminded herself it was nothing like being an adjutant, because she’d never been one. She was an officer’s wife, not an officer.

Her palms began to sweat when she heard his footsteps in the corridor outside. The other five slaves were locked in what must have once been Janis’s study. They were always locked away when the second left his apartments; Tara’s disguise as the wife of Major Vaunt had convinced Valan that she wouldn’t risk her husband’s safety by attempting to escape.

‘Welcome back, honoured,’ she said, as she did every single time, an affectation he enjoyed. He shoved his sword at her and strode into the main room, threw himself into a chair. She knelt at his feet and tugged off his boots, put them in the corner and then handed him a cup.

‘I got everything you requested,’ she said and gestured at the table. Valan grunted, rolling the wine around in his mouth as he wandered over. The fabric was arranged in what she thought was an artful sweep that hid the ragged edge where she’d cut it. The four cups and plates occupied the centre of the table along with the linens, and behind them stood the wooden horses.

A muscle flickered in Valan’s cheek. ‘I did not ask for those,’ he said.

Tara curtseyed. ‘No, honoured. Forgive me, honoured. The linens were so reasonably priced I had enough left over and more. I … was not sure whether your daughters would be able to bring any toys with them and I thought you might want to show you’d been thinking of them.’

Valan’s expression was unreadable.

‘I can try and sell them on, honoured,’ she added quickly, voice quickening with anxiety, ‘or … or use them as kindling for the fire.’

‘Expensive kindling,’ Valan commented and drank some more.

‘Forgive me,’ she said again, ‘I should not have done it. I’ll get the money back somehow, I swear. I thought—’

‘You’ve done well. Where’s supper?’

Tara bit off any more excuses and bobbed another curtsey, hurried to the smaller table set by the window where Valan liked to eat and lifted the heavy wooden cover off the plate. Cold meats, bread, cheese and greens and Tara’s stomach gurgled at the sight, wooden horses forgotten.

Valan pushed past her and sat, gestured for more wine and Tara stood by his side and watched him eat and drink food and wine that didn’t belong to him while thousands of slaves went hungry.

Her stomach rumbled again and a brief smile crossed Valan’s face. He picked up a half-eaten roll of bread and tossed it on to the floor. She stared at it, and then back at him, and then she picked it up and brushed it off and ate it.

It was three days before she could get back to the market, but the mason was still there. He’d moved along the wall a little, and while she knew nothing about masonry it didn’t look like he’d made much progress. Perhaps Vaunt had managed to get word out to slow the work and it had spread beyond the Rankers forced to do the labouring.

Tara circled the market a couple of times, wondering how best to approach the mason and what she could say, when he solved it for her. She was a dozen strides away when he reared back from the wall with the bellow of a wounded bull, a scarlet spray arcing out of the shade and across the discarded and broken stone.

The man went to his knees, clutching his hand to his chest, and Tara moved for him with the instinct of a soldier to a wounded comrade. ‘Let me see, let me see,’ she said, prising at his supporting hand. The slice across his palm wasn’t deep but it was long and bleeding freely.

‘Merol, son of Merle Stonemason who died defending this wall,’ the man hissed and then let out another bleat of pain.

‘You! What are you doing?’ a Raider demanded.

Tara stood up in order to curtsey. ‘Forgive me, honoured, I have a little skill in healing. I only thought to help so he would be able to continue working.’

‘Healer?’ the Mireces said sharply.

‘No, honoured. Just some skills I picked up over the years. I can clean and stitch this. Your will, honoured.’

Merol bleated again. ‘I can’t lose me hand, milord, please. Forgive the interruption, I’m sure I’ll be able to work again once the bleeding’s stopped.’

Tara was sure of no such thing but she held her tongue. ‘Get on with it then,’ the Raider snapped. ‘Over there, out of the way of those doing actual work. And I’ll be reporting this to your owner, bitch. What’s his name?’

‘Second Valan, honoured,’ Tara said and both Merol and the Mireces sucked in a breath. ‘Come, man. Sit down. You’re lucky my master sent me out for needle and thread among other things.’

The mason sat carefully on a broken-down crate that creaked under his weight. ‘Tara Vaunt, wife of Major Tomaz Vaunt of the Palace Rank, currently imprisoned in the south barracks in Second Circle,’ she breathed.

Merol pulled his hand out of hers. ‘Know Vaunt by reputation,’ he said quietly. ‘Didn’t know he had a wife.’ Tara got ready to run. ‘But then it’s a big city and I don’t know everything, do I? I mean, I know about walls and buildings. I know about gates.’ His eyes bored into hers. ‘I know about quiet routes from the harbours to First Circle, even, in the slaughter district.’

Tara licked her lips. ‘You know a lot, Merol; you’re clearly a useful man. But are you a loyal man?’

‘Loyal to who? I got my da’s reputation to live up to and that’s enough for me,’ Merol said and put his hand back in hers.

She broke eye contact and examined the cut. ‘Does it hurt?’

‘Nah,’ Merol said. ‘Just opened up an existing scar; barely felt it. I saw what you done the other day, how that stall-holder threatened you and you stood up to him. Made me think you were someone worth knowing.’

‘You cut your hand open for the right reasons then, Merol,’ Tara said as she dabbed at the wound and then threaded the needle and began to tug it through the flesh. ‘There are plans. I can’t say more now, but I’ll come and see you again. Where are you staying?’

‘That slimy fucker who was talking to you owns me and another lad. Think he wanted a woman – he’s ever so disappointed, keeps threatening to sell us ’cause he knows if he tries to fuck either of we’ll squash him like a fucking flea, pardon my language. But we work hard – and slow. Staying in the cloth district.’

Tara finished the stitching and bit off the thread, dabbed it some more and then wrapped a new napkin around it. So much for her spare linens – she’d have to tear them up to replace what she’d used here. ‘Sound out the other big men with hammers and wait for my word. I’ll be in touch.’ Tara stood up and repacked her basket. She turned to his owner and bobbed another curtsey. ‘He’ll need to keep it clean, honoured, or it’ll kill him.’

The Raider sucked his teeth and then spat, but he didn’t contradict her, just waved Merol towards the western wall. ‘Don’t work, don’t eat, slave,’ he growled. ‘Back to it.’

Tara made her way back to the palace and passed a knot of chained Rankers hauling stone in barrows. She slid past one, a man she vaguely recognised, definitely housed in the south barracks. ‘Mason named Merol’s with us,’ she hissed as she went past. ‘Tell Vaunt.’

She didn’t wait for a reply.

MACE

Seventh moon, first year of the reign of King Corvus

Road to the South Rank forts, Western Plain, Krike border

Three separate reports of bands of Mireces, a few hundred strong each, had come in from three locations within a ten-mile radius of the South Rank’s headquarters. Whether or not they knew the survivors of the siege were there, they were doing what they could to prevent patrols or intel moving in and out of the forts.

A week of rest had turned into a month as the Rankers finally began to let go of the state of heightened awareness and battle-readiness that had characterised their time under siege and their flight across Rilpor. Exhaustion had bitten them all deep, and for days they moved around the forts like ghosts unless a sudden sound or sight triggered them into violent motion. Mace himself couldn’t remember the last time he’d slept so much or his thoughts had been so hard to assemble. As though the siege had stolen his wits.

But now, finally, he felt close to his old self and determined to prove it to everyone by tagging along with Colonel Jarl’s Hundreds. The largest reported force was northeast between the forts and Rilporin, with others reported at north and northwest of their position – the three directions from which they were most likely to receive potential reinforcements or vital information. It didn’t feel like a coincidence that they’d be there and not elsewhere in the Western Plain.

Hallos had glowered from beneath eyebrows no less fearsome for being more grey than black these days, but Mace wasn’t letting the physician talk him out of another patrol and the chance at a scrap, even as he’d ordered the shattered remnants of the West and Palace Ranks to stand down. The fires that had led every one of them to perform extraordinary feats during Rilporin’s defence were still banked embers, and they needed time to coax the flames back into life.

Dalli had come too, which didn’t surprise him. She’d been spikier than usual since her fight with Rillirin and the girl’s removal to Fort Three, and as the days passed the outrage iced over and now they were little more than brittle strangers on the rare occasions they were in the same place together.

All of which Mace put out of his mind as they rode out of the gate in the midst of two hundred marching Rankers. ‘How are the supplies looking, Colonel?’ he asked as his skittish mount sidestepped into Dalli’s. He couldn’t even remember the last time he’d been on a horse. Somewhere back in the west, he supposed.

‘At the current rate of consumption, we’ll be on half-rations for all personnel in two moons, quarter-rations in four, and eating our horses and boot leather in six. If we go on to half-rations now—’

‘That won’t be necessary, Jarl, at least not yet. Once the civilians are gone, even with the provisions they’ll have to take with them, remaining numbers will be almost back to normal. We managed to buy up a decent amount of grain before the East Rank garrisons moved into the towns.’

‘I admit I’m hesitant about sending them so far through hostile territory though, Commander,’ Jarl said. ‘Even if the Mireces border is as empty as you believe, that’s a two-week march for Rankers, so easily three for civilians with old folks and little ones.’

‘You’re not the only one, but there simply isn’t anywhere else for them to go. If we could broker a deal with Krike to house refugees, that would be ideal, but you say we can’t.’

‘Sorry, Commander, if it was possible we’d all be suggesting it. I’ve served here for six years now and we’ve never known the Krikites to change their minds about international relations. They said no – they mean no.’

‘So, we’re going to send them to learn to be Wolves instead,’ Dalli said with half a smile. ‘Or at least, they’re going to occupy our land. Our village in the foothills is small and won’t fit them all, but it’s empty and the only place without an enemy garrison. They’ll have to dig in and build – and try not to strip the land of resources while they’re there. Some of us would quite like to go home when this is all over.’

‘Even once we’ve cleared out these Raiders it’ll be a risk,’ Mace said heavily, ‘but there are forty-two pregnant women in the forts and almost six hundred children of varying ages, as well as the old and those who can’t move fast. We can’t feed them and we can’t protect them, not indefinitely.’ He gestured at the empty, innocent-seeming land rolling away ahead of them. ‘They’re going to come for us. Sooner or later, whether or not they ever learn exactly how many of us are here, the Mireces are going to come. They can’t let us live.’

It soured the mood somewhat, but it had to be said. They weren’t safe down here in the south. Mace’s presence and that of the refugees made no difference – Corvus couldn’t allow a rested, untested fighting force like the South Rank to live. If he was to have absolute power over Rilpor, they needed to be crushed.

‘Let’s not forget Colonel Edris, though. He and King Tresh and a Listran army could be just the distraction we need to get the civs safely away,’ he added in a belated attempt to restore their spirits.

‘He’ll certainly have some decisions to make about where to attack first,’ Jarl agreed, ‘and unarmed non-combatants will be the least of his worries.’

‘Precisely.’

Turned out Jarl was like a dog with a bone, though. ‘They’ll need scouts and guards, too, someone who knows the way, wagons full of provisions. The civilians, I mean – Tresh’ll have Edris and his own supplies, of course. Then there’s deciding who goes first and how many go at once. Your march here all together was a feat worthy of a song, Commander, but the chances of you managing it undetected a second time, if you even did the first …’ Jarl trailed off.

‘You’re not telling me anything I don’t know,’ Mace grunted. He’d already talked it to death with Hadir, but Jarl struck him as the thorough type. It was possible he’d see something they hadn’t.

‘The first decision is whether we send them in small or large groups, or even one huge one – just get them out and away all together. Multiple groups increases the risk of some being seen and attacked. One large one will be slow and chaotic, hard to control. Exactly how we do it is the focus of the first meeting when we get back, but if we don’t make it, Hadir’s tasked with ensuring all four thousand civilians, minus those who have joined the militia, get out and get on the road west. Whatever it takes.’