Полная версия

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Daniel Storey 2019

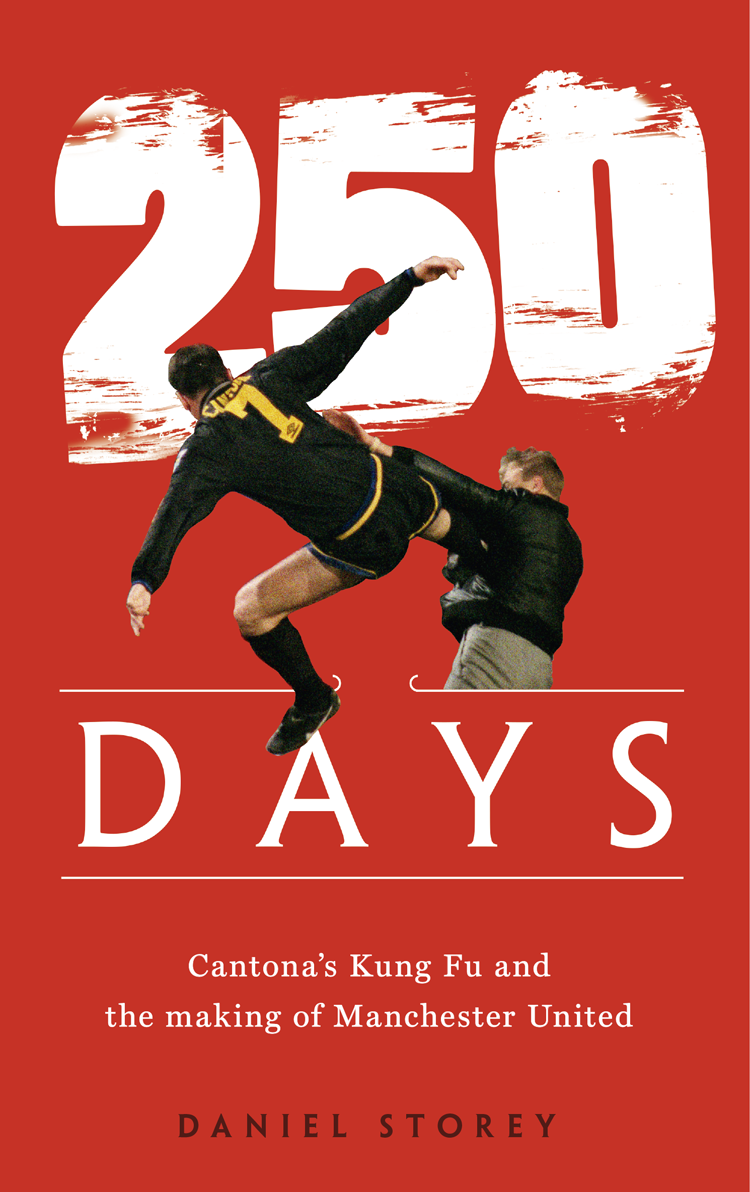

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photographs © Action Images/Reuters

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Daniel Storey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008320492

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008320508

Version: 2018-12-10

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

PRELUDE

‘Are you big enough for me?’

DAY 1

‘Go on, Cantona, have an early shower’

DAY 3

‘Good on you Eric’

DAY 6

‘When someone is doing well we have to knock them down’

DAY 66

‘When seagulls follow the trawler’

DAY 109

‘Only a fool would say it didn’t cost us the league’

DAY 157

‘You have not let yourself be affected by all this bloody nonsense’

DAY 196

‘Obviously we don’t want to lose him’

DAY 207

‘You can’t win anything with kids’

DAY 250

‘A Mancunian version of Bastille Day’

POSTSCRIPT

‘He opened my eyes to the indispensability of practice’

BIBLIOGRAPHY

About the Publisher

PRELUDE

‘Are you big enough for me?’

Eric Cantona was not the first foreign footballer in England, but he might well have been the most influential. No single player better represents English football’s rapid transformation from the working-class, kick-and-rush game of Division One – a sport that had largely remained the same for half a century – to the glamour and exoticism of the current Premier League.

Before the mid-1990s foreign players were a luxury item, mysterious circus animals tasked with performing for our entertainment. At that time, ‘foreign’ had a pejorative connotation: fancy, flash, weak-willed. Foreign imports could temporarily call England home, but it would never be their natural habitat. They would hate our weather, hate our food, hate the physicality of the game that we invented and then gave to the world. And they would soon leave for whence they had come.

That was odd, given the success of some memorable foreign imports in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa at Tottenham, Arnold Mühren and Frans Thijssen at Ipswich, Johnny Metgod at Nottingham Forest; all became fan favourites due to their natural talent and willingness to embrace the culture of their clubs. But their success did not provoke an immediate wave of immigration.

The first weekend of the inaugural Premier League in August 1992 demonstrated English football’s insular nature. The 22 clubs handed appearances to only 13 non-British players. Four of those were goalkeepers and another four (John Jensen, Michel Vonk, Gunnar Halle and Roland Nilsson) were defensively minded players.

A high percentage of foreign players in the Premier League’s early years were from northern European countries – Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands. They were preferred not only on account of their assumed comfort in dealing with the British climate, but also because they came from countries where English football was already a staple. One of the first questions asked by a club owner or manager when signing a foreign player was ‘Can he fit into the English game?’

‘Having supported and followed English football all my life, like every other Norwegian, it was a dream to play in England,’ former Swindon, Middlesbrough, Sheffield United and Bradford striker Jan Åge Fjørtoft says. ‘We had grown up with Match of the Day every Saturday night, you see.’

Of the others, Andrei Kanchelskis and Anders Limpar were two who had skill as their primary characteristic, but the pair started only 26 league games between them for Manchester United and Arsenal in 1992/93. Ronny Rosenthal was a workmanlike Israeli striker for Liverpool who had become the most expensive non-British player to join an English club in 1990. Polish winger Robert Warzycha was the first player from mainland Europe to score a Premier League goal – for Everton – but managed only 18 starts in the competition before being sold to Hungarian side Pécsi MFC.

The Premier League was therefore desperate for a poster boy. Clubs had the means to pay higher wages thanks to a broadcasting deal with Sky Sports worth an initial £304 million. Many of the top-flight stadia had been improved following the recommendations of the Taylor Report. The stage had changed; the actors had not. In late 1992 the Premier League was nothing more than the old First Division rolled in glitter and studded with rhinestones.

Enter Eric Cantona and Manchester United. In November 1992, in strolled a Marseillais enigma whose confidence was only matched by the size of his reputation. With Leeds United keen to get rid of their tempestuous Gallic star, Alex Ferguson believed he had found the player around whom he could build the first age of his dynasty.

‘If ever there was one player, anywhere in the world, that was made for Manchester United, it was Cantona,’ as Ferguson would subsequently say. ‘He swaggered in, stuck his chest out, raised his head and surveyed everything as though he were asking: “I’m Cantona. How big are you? Are you big enough for me?”’

More than any other player, it was Cantona who unlocked the door for the Premier League’s foreign revolution. He proved that the skill European and South American players stereotypically possessed need not exclude the passion and will to win of the old English First Division. Just as Glenn Hoddle and Terry Butcher – two fixtures of the England national team in the 1980s – were as disparate in style as it is possible to conceive, so too could foreign players come from any part of the footballing spectrum. If that now sounds like an unnecessary truism, it was far from obvious in 1992.

But Cantona became more than a trailblazer; he was a cultural and sporting icon. No single player was more responsible for the boom in replica shirt sales and merchandising (official or otherwise), while the ubiquity of Cantona’s face thanks to a sponsorship deal with Nike was new ground for English football. In a thousand playgrounds across the country, collars on school-uniform shirts were turned up as children mimicked the hallmark of their hero. For a few years every kid was Eric Cantona. If those children have now turned 30, many still harbour the same adoration.

Cantona’s personality could never have been so influential without talent. He scored 82 times in 185 games for Manchester United, but it was his style of play that was so unusual. Before the Premier League era there was very little tactical fluidity in English football. Defenders defended and attackers attacked, and players typically stayed in formation.

Cantona preferred a different method. He started as a nominal strike partner – usually to Mark Hughes or Andy Cole – but dropped deep in between the lines of defence and midfield, dragging immobile central defenders out of their position and comfort zone. Cantona’s technical expertise allowed him to link play effectively, and he became as renowned for his chance-creation as his finishing. Cantona is credited with 56 assists in 156 Premier League games. The only other strikers of his era to register more – Cole, Alan Shearer and Teddy Sheringham – all played at least 250 more matches.

Conversely, Cantona’s talent could never have been so influential without personality. Cantona was a leader of Manchester United not just because of his talent, but through sheer strength of character. As Roy Keane so eloquently put it: ‘Collar up, back straight, chest stuck out, he glided into the arena as if he owned the f***ing place. Any arena, but nowhere more effectively than Old Trafford. This was his stage. He loved it, the crowd loved him.’

Cantona’s unwavering self-belief – it bordered on swaggering arrogance – was not a natural trait, but a deliberate tool of his success. ‘I’ve said in the past that I could play single-handedly against eleven players and win,’ he wrote in Cantona on Cantona. ‘Give me a bicycle and I believe I can beat Chris Boardman’s one-hour record.’ In Cantona’s psyche there was no room for doubt. Doubt is what leads to fear, and if fear cannot be controlled it eventually defeats you.

The Cantona effect at Manchester United became extraordinarily influential, but he was doubted when he joined. In hindsight, Leeds and their manager Howard Wilkinson are mocked for letting Cantona go, but they made a profit on the transfer fee they had paid to Nîmes less than 12 months earlier and had endured a rocky relationship with the Frenchman. Cantona failed to click with striker Lee Chapman, and later revealed his unhappiness at Elland Road. Wilkinson did the same: ‘Eric is not prepared to abide by the rules and conditions which operate for everybody else here.’

‘I had a bad relationship with the manager, Wilkinson,’ Cantona told FourFourTwo in 2008. ‘We didn’t have the same views on football. I am more like a Manchester footballer. At Leeds, football was played the old way – I think you say kick then rush. If I don’t feel the environment is good, I don’t want to be there.’ Cantona is right to some extent, but underplays his own role in United’s ‘new way’.

Senior Manchester United players Gary Pallister, Steve Bruce and Bryan Robson all raised significant concerns among each other and to the club about Cantona’s reputation for upsetting team morale, but Lee Sharpe was the most candid. ‘This bloke’s a total nutter, what are we doing?’ he is quoted as saying. The national media were hardly warm in their congratulations to Ferguson for his signing.

But Ferguson realised that his club needed a shot in the arm. They had finished second to Leeds the previous season, but sat eighth in the table with summer signing Dion Dublin out injured. Ferguson’s team had won two of their previous 13 matches, and there were lingering doubts over the Scotsman’s job security. United had not won the league title for 25 years.

Ferguson spoke to then-France national team manager Gérard Houllier for advice on Cantona, but also leant on Michel Platini and journalist Erik Bielderman for their input. The conclusion from all three was that Cantona needed a father figure, while Ferguson needed a new leader. Both men fitted the other’s need perfectly. Cantona only had problems with authority when he did not respect it.

His impact was instantaneous. Manchester United won eight and drew two of his first ten league games, and the split across the whole of 1992/93 is striking: 1.5 points per league game before his arrival and 2.3 points per league game afterwards; 1.06 goals per league game before his arrival and 1.92 goals per league game afterwards. From being eighth in the league and nine points from the top, United finished the season as league champions, with a ten-point cushion to second place.

Alongside the results, Cantona changed the mood too. By New Year’s Day 1993 Ferguson was publicly enthusing about Cantona’s effect on every element of Manchester United. ‘More than at any time since I was playing, the club is alive,’ he said. ‘It’s as if the good old days are back and the major factor, as far as I’m concerned, is the Frenchman.’

Manchester United’s former greats lined up to pour on praise. ‘I can’t think of anyone who I would rather wear my crown,’ said Denis Law. George Best was even more effusive: ‘I would pay to watch Cantona play. There are not many players over the years I would say that about. He is a genius.’ Old Trafford had its new king.

But the appeal of Cantona lay not just in his achievement, but also the controversy. Like another famous No. 7 at Manchester United who courted headlines off the pitch as much as on it, Cantona’s misdemeanours did not detract from his legacy; they cemented it. Cantona’s popularity with supporters is explained very simply: he was one of them. Here was a superstar, but with the flaws of Everyman laid proudly bare for all to see.

Never were those flaws more exposed than at Selhurst Park on 25 January 1995. Cantona’s acrobatic assault on Matthew Simmons provoked one of the longest bans for an on-pitch offence in the history of English football, and created a media circus the like of which the sport had never witnessed. Moreover, it threatened to force Cantona’s departure from England in the same manner in which he had left France, ignominy trumping all else. Had this happened, Cantona’s reputation at Old Trafford would have been very different.

Ferguson risked his own reputation over Cantona, but also acceded to him. This is captured in one memorable Steve Bruce anecdote. The squad were invited to Manchester Town Hall for a civic reception, and required to wear club suits. Cantona turned up wearing flip-flops, ripped jeans and a long, multi-coloured coat. As captain, Bruce was instructed to tell the manager that several players weren’t happy with Cantona’s appearance, believing it to be disrespectful.

‘Fergie’s on the red wine,’ Bruce recalls. ‘He puts down his glass, looks over at Eric. “Tell them from me, Steve,” he says, “that if they can play like him next year, they can all come as fucking Joseph too.”’

So when Cantona did step out of line so spectacularly in January 1995, Ferguson inevitably felt let down and wrestled with his own moral compass as well as what was best for Manchester United. In sticking by his man, Ferguson doubled down his trust in an enigma when others in his position would have taken an alternative – and easier – route. It proved to be a masterstroke.

For all the focus on Cantona during the 250 days between kung-fu kick and return to the pitch, Manchester United changed too. Ferguson started an evolution that began with a mini-revolution: senior players were sold but not replaced, while extraordinary faith was placed in a crop of prodigious young talent. During that summer, with Manchester United neither the reigning Premier League nor FA Cup champions, Ferguson would have his judgement called into question. The great manager even admitted to doubting himself. That didn’t happen often.

The ‘Class of 92’, as they would be nicknamed in hindsight, were already on the fringes of United’s first team when Cantona assaulted Simmons, but Ferguson brought them to the front and centre of his vision in the Frenchman’s absence.

Cantona’s role in that process has been too easily overlooked. His ban enabled him to play tutor and mentor to a wonderful generation of academy graduates. In turn it helped establish Ferguson’s first dynasty as Manchester United manager.

‘He changed the mentality and changed the way of everything,’ Peter Schmeichel said. ‘All the kids we’ve seen grow up with Manchester United from that period, they’ve really benefited from that and you could go and speak to David Beckham, Gary Neville and Paul Scholes about him. They will always point to him, as he was the guy.’

It is wonderfully fitting that Cantona’s first game back, against Liverpool at Anfield, was the first match in which all six of the ‘Class of 92’ appeared in a Manchester United shirt: Gary Neville, Phil Neville, Nicky Butt and Ryan Giggs as starters, David Beckham and Paul Scholes as substitutes.

This is the story of Cantona’s lasting impact on Manchester United, told through the 250 days between assault and comeback. A man whose temperament was questioned when he signed ultimately failed to escape his imperfections. But rather than erode his and Ferguson’s legacy, it only helped to define both.

DAY 1

‘Go on, Cantona, have an early shower’

At 8.57 pm, Steve Lindsell got the shot.

Lindsell had gone to Selhurst Park on a Wednesday evening to watch Manchester United try to move to the top of the Premier League and witness the third anniversary of Eric Cantona’s arrival in English football through the lens of his camera. He was positioned on the touchline, primed. He would hope to sell a few choice photos – a goal celebration, frustration etched onto a contorted face, a manager thrusting his hands in pockets to protect against the cold January night – to several media outlets.

Right place, right time. Midway through the second half, Lindsell hurriedly clicked his shutter and took the photos that captured the most outrageous moment of the Premier League’s first decade. The most famous footballer in the land had both feet off the ground. One was planted into the chest of a supporter. Around him, fans who had rushed to the ground after work, or paced the same walk from their homes as they had done a hundred times before, watched on. Just another home game had become a match they would never forget.

‘I snapped, and snapped again,’ Lindsell said. ‘I thought I had a good picture but couldn’t imagine the impact it would have. I went to my van outside Selhurst Park, printed the roll, which must have taken me 15 to 20 minutes, then sent the pictures. It was only the day afterwards that all hell broke loose.’

Before the 48th minute Cantona had been a passenger in an uneventful game. Palace, just outside the relegation zone on goal difference, had broken up play effectively and limited Manchester United to a series of half chances. This was largely due to the man-marking job done on Cantona by Palace central defender Richard Shaw, who had been instructed by manager Alan Smith to stay touch-tight to the Frenchman.

Smith and Shaw would later insist that the defender was merely doing his job, but Cantona spent the first half complaining about the physical treatment that referee Alan Wilkie had either failed to spot or chosen to ignore. The reality is that Shaw left his foot in on more than one occasion to both put Cantona off his game and try to rile the Frenchman. It was common practice at the time; the hallmarks of the old First Division hadn’t quite been erased.

Wilkie remembers Cantona chastising him as the players left the field at half-time – ‘No yellow cards!’ – and the Frenchman repeating the message as the players waited in the tunnel to come back out for the second half. But, as ever, it was Ferguson’s message that most stuck in Wilkie’s mind. ‘Why don’t you do your fucking job?’ was the Manchester United manager’s presumably rhetorical question. This was par for Ferguson’s course.

What is certainly true is that Ferguson had spoken to Cantona in the dressing room at half-time to warn him not to get involved in Shaw’s games. ‘Don’t get involved,’ he quotes himself as saying in his autobiography. ‘That is exactly what he wants. Keep the ball away from him. He thinks he is having a good game if he is tackling.’

As an experienced – and very capable – central defender, seeing Cantona’s frustration was only likely to make Shaw step up his strategy. You could hardly blame him. Palace could not hope to contend with United on ability.

‘It was all Shawsy’s fault as well,’ Shaw’s teammate John Salako later said with his tongue inserted in cheek. ‘Richard was the best man-marker ever. He had a job to do on Eric and he did it so well Eric got so frustrated he literally booted Shawsy up the arse. Eric lost the plot.’

Three minutes into the second half, Peter Schmeichel launched a goal kick forward and Shaw and Cantona clashed again. Shaw was certainly the first to commit an offence – the linesman flagged to indicate as such – but it was Cantona’s kick-out at Shaw that earned the wrath of the officials. It clearly constituted violent conduct, and Wilkie was left with no choice but to show Cantona a red card. On the touchline, Ferguson was incandescent with anger.

Later, in court, Cantona would accept Wilkie’s decision to send him off but complained at his treatment by Shaw. ‘In my opinion, his decision was correct,’ he said in a statement read out by his barrister David Poole, ‘although I had been repeatedly and painfully fouled in the course of the match.’

One of the direct results of the Cantona incident was that the rule was changed regarding post-red card events. Until the end of the 1994/95 season a player in English football would leave the field at the nearest point following their dismissal. Then followed what was a potentially long walk around the perimeter of the pitch to the tunnel, often passing large swathes of opposition supporters who had free rein to offer their own personalised farewell messages. From August 1995 onwards, players left the field in a direct line towards the tunnel. In hindsight, it is extraordinary that it was ever different.

It does not condone Cantona’s subsequent actions, but the atmosphere at Selhurst Park was notoriously raucous and there is no doubt that any opposition player making the walk in front of the Main Stand would have faced many hundreds of taunts and foul-mouthed tirades.

But for Cantona, that abuse was worse than usual because of who he was, where he came from and which team he played for. Twice Cantona can be seen looking up to the stands in response to particular fans, but after a momentary pause he walks on.

‘It wasn’t just the tackles and shirt pulling he had to deal with that night that pushed him over the edge,’ said then-teammate Gary Pallister in 2015. ‘It was the culmination of a lot of abuse Eric had to put up with at every ground he went to.

‘You wouldn’t believe the kind of vile verbal abuse that was directed at him when we arrived at opposition grounds and got off the bus. Even when we went to the horse races, Eric couldn’t escape it. I remember at one race meeting he was being spat on from a balcony in the enclosure above where we were standing. He was a target, there was no doubt about it.’

One of those supporters delighting in Cantona’s ignominious and premature departure from the pitch was 20-year-old Matthew Simmons. Eye-witnesses said that Simmons had rushed down 11 rows of the Main Stand in order to get as close as possible to the Frenchman to abuse him, though Simmons would later claim that he was merely leaving his seat to visit the toilet.

The language Simmons used is also open to interpretation. Rather comically, he claimed to police in a follow-up interview that he had used the words ‘Off, off, off. Go on, Cantona, have an early shower.’ A slightly different account was heard in court by a witness attending the game as a neutral, and who quoted Simmons as shouting, ‘You fucking cheating French cunt. Fuck off back to France, you motherfucker. French bastard. Wanker.’