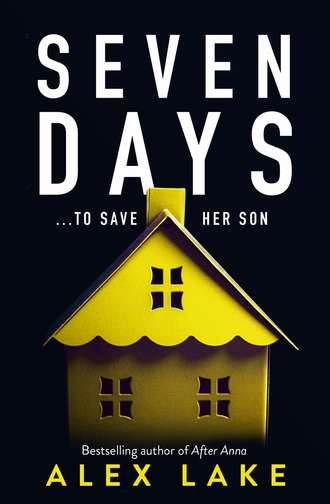

Seven Days

Полная версия

Seven Days

Жанр: книги по психологиизарубежные любовные романысовременная зарубежная литературазарубежная психология

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу