Полная версия

John Carr

JAMES DEEGAN MC spent five years in the Parachute Regiment, and seventeen years in the SAS.

He served for most of that time in a Sabre Squadron, from Trooper to Squadron Sergeant Major, and saw almost continuous service on operations in Northern Ireland, the Balkans, Africa, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. He fought in both Gulf Wars, and was on both occasions amongst the first Coalition soldiers to cross the border into Iraq. He was twice decorated for gallantry and, on his retirement from the Special Air Service, as a Regimental Sergeant Major, he was described by his commanding officer as ‘one of the most operationally experienced SAS men of his era’.

He now works in the security industry, in some of the world’s most hostile and challenging environments. His first John Carr novel, Once a Pilgrim, was published in January 2018.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © James Deegan 2019

James Deegan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9780008229542

Praise for James Deegan:

‘Brilliant.’

Jeffrey Archer

‘Inevitably Deegan will be compared to Andy McNab and Chris Ryan, but he adds his own brand of contemporary authenticity. Carr is a hero for our times.’

Daily Mail

‘As close as it gets to the real thing.’

Mark ‘Billy’ Billingham MBE, former SAS Warrant Officer and star of TV’s

SAS Who Dares Wins

‘James Deegan writes with masterful authority and unsurpassed experience.’

Chantelle Taylor, Combat Medic and author of Battleworn

‘Authentic detail and heart stopping narrative grips you from the outset bringing the shadowy world of today’s special forces bursting in to life in a way that other authors of the genre couldn’t hope for … the best thriller I’ve read in years.’

Major Chris Hunter QGM, author of Eight Lives Down and Extreme Risk

‘Exposes the raw with the reality. This is a gripping high intensity drama.’

Bob Shepherd, ex SAS Warrant Officer and bestselling author

‘Move over Andy McNab and Chris Ryan, there’s a new SAS veteran writing thrillers and he’s good. Very good.’

Stephen Leather

‘An impressive debut, that rates up there with Gerald Seymour and Fredrick Forsyth; blending a realistic vernacular of special forces soldiering to make a cracking read with page turning pace from start to finish.’

Stuart Tootal

TO ALL THE BRAVE MEN I HAVE KNOWN WHO WILL NOT SEE OLD AGE. THEY ACCEPTED THE RISKS, THEY STEPPED INTO THE BREACH, AND PAID THE ULTIMATE PRICE.

UTRINQUE PARATUS

WHO DARES WINS

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

THIS IS A WORK OF FICTION.

NONE OF THE EVENTS DESCRIBED HAPPENED, AND NONE OF THE CHARACTERS CONTAINED IN THE NARRATIVE ARE BASED ON ANY PERSONS, LIVING OR DEAD, UNLESS EXPRESSLY STATED.

O turn your eyes to where your children stand

From The Story of Hassan of Baghdad and How He Came to

Make the Golden Journey to Samarkand (1913)

JAMES ELROY FLECKER (1884-1915)

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PROLOGUE

PART ONE

Chapter 1.

Chapter 2.

Chapter 3.

Chapter 4.

Chapter 5.

Chapter 6.

PART TWO

Chapter 7.

Chapter 8.

Chapter 9.

Chapter 10.

Chapter 11.

Chapter 12.

Chapter 13.

Chapter 14.

Chapter 15.

Chapter 16.

Chapter 17.

Chapter 18.

Chapter 19.

Chapter 20.

Chapter 21.

Chapter 22.

Chapter 23.

Chapter 24.

Chapter 25.

Chapter 26.

Chapter 27.

Chapter 28.

Chapter 29.

Chapter 30.

Chapter 31.

Chapter 32.

Chapter 33.

Chapter 34.

Chapter 35.

Chapter 36.

Chapter 37.

Chapter 38.

Chapter 39.

Chapter 40.

Chapter 41.

Chapter 42.

Chapter 43.

Chapter 44.

Chapter 45.

Chapter 46.

Chapter 47.

Chapter 48.

Chapter 49.

Chapter 50.

Chapter 51.

Chapter 52.

Chapter 53.

Chapter 54.

Chapter 55.

Chapter 56.

Chapter 57.

Chapter 58.

Chapter 59.

Chapter 60.

Chapter 61.

Chapter 62.

Chapter 63.

Chapter 64.

Chapter 65.

Chapter 66.

Chapter 67.

Chapter 68.

Chapter 69.

Chapter 70.

Chapter 71.

Chapter 72.

Chapter 73.

PART THREE

Chapter 74.

Chapter 75.

Chapter 76.

Chapter 77.

Chapter 78.

Chapter 79.

Chapter 80.

Chapter 81.

Chapter 82.

Chapter 83.

Chapter 84.

Chapter 85.

Chapter 86.

Chapter 87.

Chapter 88.

Chapter 89.

Chapter 90.

Chapter 91.

Chapter 92.

Chapter 93.

Chapter 94.

Chapter 95.

Chapter 96.

Chapter 97.

Chapter 98.

Chapter 99.

Chapter 100.

Chapter 101.

Chapter 102.

Chapter 103.

Chapter 104.

Chapter 105.

Chapter 106.

Chapter 107.

Chapter 108.

Chapter 109.

Chapter 110.

Chapter 111.

Chapter 112.

Chapter 113.

Chapter 114.

Chapter 115.

Chapter 116.

Chapter 117.

Chapter 118.

EPILOGUE 1

EPILOGUE 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Extract

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

THE TWO MEN knew each other of old, having fought as brothers-in-arms in various places over many years, but they had not seen each other in person for a long time.

Life for men like them had become a good deal more challenging and dangerous since September 11, 2001, so their contact was restricted to darknet chatrooms, snatched conversations on encoded VOIP systems, and, once in a blue moon, cryptic notes passed via trusted intermediaries.

Their secret conversations through these unorthodox channels were often surprisingly banal. One would grumble about the filthy weather in the grubby little town in which he was currently hiding, and the other would counter with complaints about the terrible food in his present, miserable location.

On the rare occasions when the mood was lighter, they talked of happier times, and of their families. Each had a wife and children back home, but neither expected ever again to kiss his wife nor hold his children; the path they walked was a path of shadows and sorrow, and it led in one direction only.

Their lives were full of uncertainty, and privation, and fear, and precious few comforts and the wise man cut his ties, of friendship and of blood, permanently.

Death stalked them daily, and, being only human, they sometimes wondered how it was that they, who had given so much, had ended up living like rats, while others, who had given so little, lived like kings.

Why were their days all stone and no fruit, all grit and no pearl?

Of course, each tried hard to cast this unworthy thought from his mind; it was dangerous to harbour such ideas – and not merely in the spiritual sense.

That had been the way of their lives for so long that they had almost – almost – forgotten what it was like to live normally.

And then, one day, the younger of the two men contacted his older friend via a mobile telephony app with secure, end-to-end encryption.

After the usual small talk, the younger man – a giant Chechen called Khasmohmad Kadyrov, who was presently living in a cramped room in a safe house in Cairo – made a tentative suggestion.

Very tentative.

What, he asked, if there were a way in which they might both strike the enemy and – and he tried hard not to be vulgar about this – achieve a more… earthly reward for themselves?

At first, the older man – a Yemeni called Saeed al-Shafra – was sceptical, and even hostile.

But this was something of an act.

Al-Shafra was nearly sixty, now, and he had grown tired, and listless, and, as he looked around the spartan room, in his modest, baked-mud home, in the compound on the edge of the dusty village in the dreary Balochi outpost of Nushki, it occurred to him that he was perhaps even a little bitter about the turns his life had taken.

‘Go on,’ he said.

‘I have a friend,’ said Kadyrov, hesitantly. ‘A good friend, from the old days. I mean, a long way back – he’s from Vedeno, fought with the 055 at Mazar-e Sharif.’

‘I missed that party,’ said the Yemeni. ‘So many men, slaughtered like goats.’

‘Indeed,’ said Kadyrov. ‘But my friend was lucky. He got injured, some shrapnel took a chunk out of his right calf, so he got taken away before the massacre.’

‘In that sense,’ said the older man, ‘he was fortunate.’

‘I saw him last in Now Zad,’ said the Chechen. ‘Or perhaps the Korengal. I can’t remember, exactly. He’s a fighter, but lucky again, because the Americans’ – he almost spat the word – ‘they don’t know him. This is the beauty of it. Two years ago, he’s in Islamabad, he flies to Turkey, then travels to Germany. Nobody says a word to him, nobody even looks at him. For the last year, he is in England, in London. There he has made a very good contact, with someone who has a very interesting situation. Very interesting indeed. But we need funding and I know that you can find money for us.’

Khasmohmad Kadyrov talked some more, and the Yemeni called al-Shafra listened, and he smiled.

And the more he listened, the more he smiled.

And when Kadyrov had finished talking, Saeed al-Shafra looked out of his window, across the empty, sun-baked Balochi desert, which lay between his humble home and Afghanistan’s distant Helmand River, and he chuckled.

‘Oh, Khasmohmad,’ he said. ‘Khasmohmad, Khasmohmad. Truly, this is a gift from Allah.’

PART ONE

1.

AT SEVEN-THIRTY, half an hour before unlocking, the prison came banging and rattling and echoing to life.

But Zeff Mahsoud and his cellmate had been up since well before sunrise, in order to perform their fajr.

Now they sat facing each other, Mahsoud on a tubular chair pushed hard against the cream-painted wall, the other man on his steel-framed bed.

‘I have a good feeling about today, brother,’ said the cellmate. ‘I think it will be good news.’

‘Inshallah, Hamid,’ said Mahsoud. ‘Time will tell.’

‘Be confident. Tonight you will be in your wife’s arms. Tomorrow…’ Hamid paused, and lowered his voice. HMP Belmarsh was not a place which rewarded the incautious. ‘Tomorrow, who knows?’

Mahsoud smiled. ‘Who knows indeed?’ he said.

Lazily, he got up and walked to the cell door, bending down to pick up the breakfast tray which had been handed over the previous night.

A plastic bowl of own-brand cornflakes, a carton of UHT milk, and a bread roll: he curled up his lip.

‘You’ll visit my friend?’ said Hamid. ‘Like I said?’

‘If I am released…’

‘You will be.’

‘If I am released, then yes, I will visit your friend.’

‘He will be most interested to meet you. I think he will have very interesting proposals for you.’

‘I hope so.’

‘I know so. He has big plans. Dramatic plans.’

Zeff Mahsoud smiled.

Cornflakes in hand, he walked over to the small window, and looked up at the clear blue skies over south-east London.

Seven or eight miles away, over Bromley, a passenger jet was climbing away through 6,000ft.

Mahsoud watched it go.

Three hundred souls and a hundred tonnes of aviation fuel, in a thin aluminium tube.

So thin.

So vulnerable.

‘I have plans of my own, brother,’ he said.

But I’m afraid I cannot share them with you, he thought.

2.

SEVERAL MILES NORTH, on the other side of the river, Paul Spicer – senior partner at the human rights law firm Spicer, McGraw and Hill, and long a thorn in the side of the government – was already at his table in the Booking Office restaurant at the St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel.

He was eating a much grander breakfast, his plate piled high with crispy bacon and waffles, drizzled with maple syrup in the American style.

He ate methodically, his chin wobbling as he chewed, pausing only to drink from his cup of strong black coffee.

Around him buzzed smart waitresses, eager waiters.

On his left, the morning maître d’ showed another small group of businessmen to their seats, smiling unctuously.

At 7.45 a.m., Emily Souster joined Spicer.

Slim and elegant in her grey trouser suit.

Roedean and Cambridge.

Blonde.

Stunningly pretty.

At one time, Spicer had half-hoped… But she’d made it quite clear that there was no chance of that.

Emily sat down and looked at him, eyebrows raised.

Said, in her cut-crystal Queen’s English, ‘How on earth can you eat that?’

‘Easy,’ he said, in his broad Leeds. ‘Open your gob, shove it in, and chew.’

She shuddered. ‘I’m a bag of nerves,’ she said.

A waitress came over.

Took her room number and her order – no food, just a fresh pot of coffee and a glass of orange juice.

Spicer said, ‘What’s there to be nervous about?’

‘Aren’t you?’ she said.

‘No. I’m ninety per cent certain we’re going to win. And even if we don’t…’

Even if we don’t, we bank our money and move on.

He left it unsaid.

Shot her a glance.

The junior solicitor sitting across the breakfast table from him was a true believer: a passionate human rights lawyer, a righter of wrongs, a romantic burner of midnight oils in pursuit of every cause she could find.

Why was it so often like that?

Emily had known every advantage in life – an ambassador father, the best education money could buy, a trust fund to fall back on… If you grew up like that, it allowed you the space to spend what felt like half the year working pro bono, seconded to crew aid convoys, and going on marches and demonstrations.

Whereas, if you grew up like he had – born to a single mum in Harehills, eating chip butties for tea, sharing bathwater with three brothers…

Make no mistake about it, he loved the challenge, loved picking holes in the government’s cases, but if you came up like that then you knew the value of a quid.

‘There’s no even if we don’t, Paul,’ said Emily. ‘We have to win. We can’t let him rot in there for the next fifteen years.’

Spicer smiled absently.

‘I’ll say one thing, Emily,’ he said, forking half a waffle into his mouth. ‘It won’t be for want of trying.’

3.

AS HE SAID that, Charlotte Morgan was getting out of the shower of her flat in Pimlico, and wrapping a towel around her dripping body.

She opened the door and leaned out.

‘What time is it?’ she shouted, wrapping another towel around her wet hair.

‘Quarter to eight,’ came the reply from the bedroom. ‘You’ll be fine.’

‘Bloody alarm,’ said Charlotte, half to herself.

Eddie appeared in the doorway of their bedroom, in his boxers and a white T-shirt.

‘You’ll be fine,’ he said, again. ‘It’s only twenty minutes. I’ll make you a cup of tea and some toast.’

‘Half an hour, if the traffic’s bad,’ said Charlotte. ‘I need to be there by nine. And my hair’s still soaking.’

‘You just crack on,’ he said. ‘I’ll check the cab’s booked.’

He passed her, and they kissed, before he disappeared downstairs, and she walked through to the bedroom to begin drying her hair.

Clicked on the Today programme.

‘…in the case of Zeff Mahsoud.’

The voice of the BBC Radio 4 presenter drifted from the speaker.

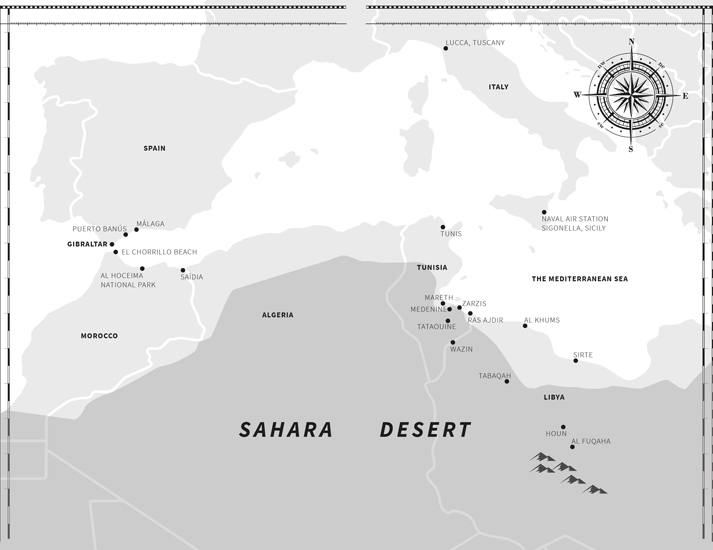

‘Mr Mahsoud, a charity worker from Yorkshire, you’ll remember, was arrested after arriving home to the UK on a flight from North Africa. He maintained that he’d been on a humanitarian mission to Libya, but six months ago he was given a lengthy jail sentence for terrorism-related offences. He has always protested his innocence, and an increasingly noisy campaign for his release has led us to the Court of Appeal where, later today, his case will be re-considered. Whatever their lordships decide, the appeal has thrown into sharp relief a number of questions about the operations of both MI5 and MI6, and…’

She clicked the clock radio off.

She most definitely didn’t need that.

4.

AT JUST BEFORE 8 a.m., Zeff Mahsoud was taken from his cell to the holding area.

There he was handcuffed to a prison officer, who led him through three sets of steel doors to the cold air outside.

He breathed in deeply, despite the diesel fumes which were filling the vehicle yard.

Overhead, the blue sky was slowly clouding over, but still he felt an overwhelming sense of release.

No matter who you were, and what you were doing there, prison was prison, and Belmarsh was worse than most.

Several police officers, wearing body armour and carrying MP4s fitted with suppressors, watched with undisguised contempt as he was loaded into the back of a prison transport vehicle.

There was a short delay as they waited for an armed robber whose appeal was to be heard on the same day, and then the truck fired up and lurched out of the prison gates, sandwiched between two Met Range Rovers and assisted by a pair of motorcycle outriders.

It’s an hour dead from Belmarsh in Woolwich to the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand – for ordinary vehicles.

With their sirens and blue lights, and the motorcyclists zipping ahead to hold up crossing traffic, they made it in forty minutes.

On arrival in the secure parking area, Mahsoud was debussed and led into a cell in the bowels of the court.

Paul Spicer and Emily Souster were waiting nearby, and were shown to the cell a few moments later.

Spicer and Mahsoud shook hands – Emily knew better than to offer hers – and Spicer cleared his throat.

‘I’m pretty confident, Zeff,’ he said. ‘As discussed, we’ve a strong case and you’ll not find a better pair to put it across than Jim Caville and Charlotte Morgan. But nothing in life is guaranteed, as I’ve said, and there’s always the risk that the judges won’t see it our way.’

Zeff nodded.

‘It wouldn’t necessarily be the end,’ said Emily Souster. ‘Even if they find against us, there are other avenues. The Supreme Court, the European Courts…’

Mahsoud held up his hand. ‘Please,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry. I have every confidence.’

For a moment, he looked almost preternaturally calm.

Then, as though he’d been in something of a daze, he shook his head slightly.

‘But, of course,’ he said, ‘if we fail we will fight on.’

5.

THREE HOURS LATER, five people stood on the Strand in London, in the shadow of the Royal Courts of Justice, and waited for the hubbub to die down.

On the left were James Monroe Caville QC and his junior, Charlotte Morgan, in black gowns, barristers’ wigs in hand, smiling.

Then Emily Souster, carrying a leather case across her middle.

Next to her was Zeff Mahsoud, in a dark, ill-fitting suit, a serious, even angry, expression on his face.

And next to Mahsoud was Paul Spicer – pink and plump, and wearing collar-length hair and a suit which fit him very nicely indeed. Three thousand pounds, bespoke, from Gieves & Hawkes, so it should.

Spicer held up a hand. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, please,’ he said, raising his voice over the traffic noise. ‘I have a statement to read on behalf of my client, Mr Mahsoud.’

The hubbub slowly died down.

Spicer cleared his throat and looked down at the sheet of A4 paper in his hand.

‘Today is a great day for British justice and the British people, and a terrible day for the repressive agents of the British State,’ he read. ‘Two years ago, on my return to this country from a fact-finding and aid expedition to Libya, I was detained by the border authorities at Gatwick Airport. I was held on remand for six months, and astonishingly, although I was wholly innocent, I was eventually convicted of several terrorism offences and given a substantial prison sentence. I have since served a further six months of that sentence. Today the Court of Appeal found that my convictions were unsafe.’