Полная версия

Performance Under Pressure

As much as our mental blueprint is laid down during our childhood, one of the major discoveries of modern science has been that our brain continues to adapt and adjust itself at the microscopic level throughout our life. Remarkably, if part of the brain is damaged, then other nerve cells, especially the adjacent ones, can sometimes help out to compensate for the loss.

Much like the memories in our brain, the patterns encoded in our nerve-cell networks when we were young still influence how we feel and act in current situations. Like a pathway through a forest, the more we use the same nerve-cell pathway, the clearer and easier it becomes. We find ourselves following the path without really thinking why we are doing it; it just feels natural. Which it is: it is now in our nature to react a certain way in difficult moments.

The opposite is also true. If we stop using a particular pathway, it will become overgrown and not so easy to go down. In a high-pressure situation, every time we resist the urge to escape the discomfort by following a certain path, that nerve-cell escape path is weakened – and the uncomfortable path is strengthened. What we consciously experience is that the urge to escape that moment is reduced and we can tolerate a little more discomfort.

The pathways in our brain are constantly being strengthened and weakened. We strengthen the impulse to escape every time we reward it by moving away from discomfort – and we weaken it every time we tolerate the urge to move away.

Our performance habits are not random. If we want to change our performance under pressure, then we need to change the biology that drives it.

The RED–BLUE tool is all about being comfortable being uncomfortable. Under pressure, do we give up or rise up? As someone wise once said: ‘Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.’

THE HUMAN BRAIN

Structure & function

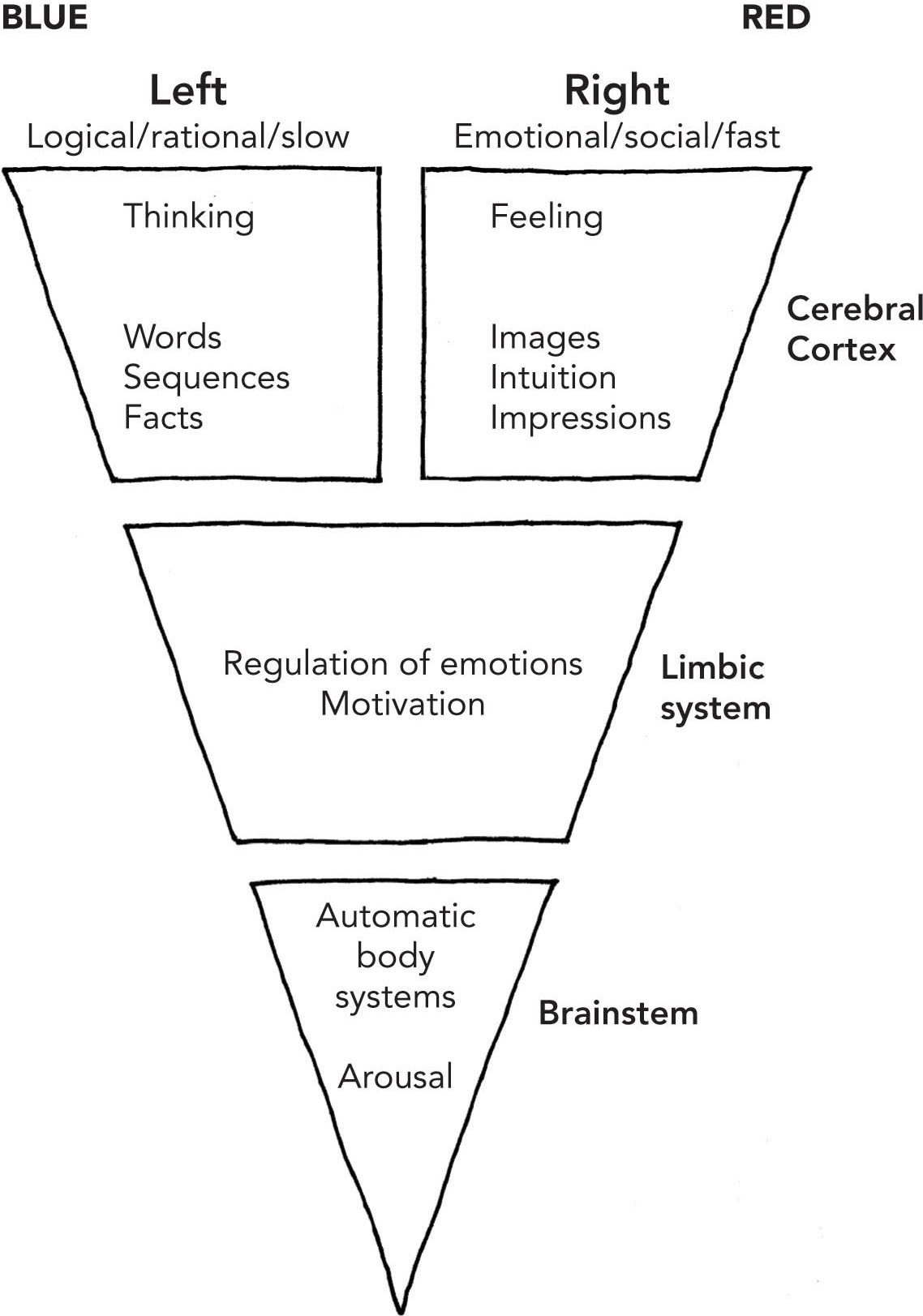

The brainstem and limbic system connect primarily with the right hemisphere to provide emotional regulation, operating through images, feelings and direct experience (RED). The left hemisphere operates through language, logic and reflection (BLUE).

CHAPTER 3

Chapter 3, Balanced Brain vs Unbalanced Brain

Our emotional regulation system sits at the heart of our performance under pressure.

Our RED system evolved through repeated connections with our primary caregivers, and this determines how much feeling we can tolerate and how flexible our responses are when we become uncomfortable.

Far from being a wishy-washy system of feelings and sensations, the RED system is the primary driver of our psychological reaction in pressure situations. Our emotional blueprint – laid down in our first two years and constantly revised through life experience – has a lot to do with how we respond to pressure, and whether we become prone to unhelpful behaviours. When our emotional regulation is poor and RED dominates, our attention becomes divided or diluted and our focus is dragged away from the present moment. We lose emotional flexibility and the ability to think clearly and our behaviours default to basic survival instincts, out of keeping with the situation.

In my experience the most commonly identified pattern is for performance under pressure to cause over-arousal – too much RED – rather than under-arousal. But one trap is to assume that under-arousal comes from too little emotion, when in fact it often comes from too much anxiety and tension and a partial freeze reaction. Going ‘flat’ can look relaxed, but is actually very different – and is sure to lead to poor performance.

Trying to ignore or suppress our RED mind is a weak strategy, because it has evolved to never be snubbed or shut down. In fact, trying to overlook it actually powers up our RED response until it gets our attention. If need be, it will take over and make its presence felt.

But whatever template we have now does not fully determine how we respond to pressure. Our BLUE system is designed to exert some control over the feelings and impulses that emerge when we are emotionally uncomfortable. Our BLUE mind can kick in to provide balance and control of our RED system, and we can get the two systems back in sync.

Our BLUE system controls RED emotion first of all by naming it – remember our left hemisphere has the power of language – and simply naming a vague, hard-to-describe physical experience has a very settling effect. Our BLUE system can then reappraise the situation by focusing on the negative experience and modifying its meaning. Left-brain naming and meaning-change dampen down the RED emotional intensity.

It’s important to remember that the RED system is not inherently good or bad, any more than emotions are good or bad. Our feelings are a normal and essential part of life. Without them we would never experience the joy of close connections or the thrill of chasing goals and achieving them. The RED emotional system is what gives us drive and energy; it gets us going. It’s just when RED goes into overdrive and we lose control that we meet problems.

It would be a serious mistake to label RED as bad and BLUE as good. Both systems are very useful for their intended purposes. Too much RED may be more common, but being too BLUE can be just as harmful to performance. It can cause us to lose emotional connection, becoming detached, aloof and even cold. Team spirit would be impossible within a completely BLUE world.

This book is fundamentally about finding our RED–BLUE balance, not about casting RED as a villain and BLUE as the hero of the piece.

My aim is to help you perform effectively when you’re out of sorts and stressed, not when it’s plain sailing. As we’ve learned, under pressure we will experience discomfort, so we need to learn to be comfortable being uncomfortable – not just coping with discomfort, but thriving within it.

How well we perform depends on the quality of our attention. And our control of attention is driven by the interaction between our RED and BLUE mind systems.

Whether RED and BLUE are in sync or out of sync will have a large say in whether we can perform under pressure. If we are badly prepared, pressure can take us down. If we are well prepared, pressure can lift us up to new heights.

In this chapter, I’ll look at the most common ineffective patterns of feeling, thinking and acting under pressure, and contrast them with the most common effective patterns of feeling, thinking and behaving under pressure. Understanding these patterns provides us with a better chance of detecting when we are going off track, and more idea of how to get back on track once it happens.

Threat vs Challenge

Threat

Tony is running late for an important meeting at work with his boss. He has tension in his neck and shoulders, his heart and thoughts are racing, and he feels a little sick. There’s no direct physical threat here. He knows that in the same situation, most of his colleagues would not be bothered at all. If he does arrive late his boss probably won’t even comment. But still he feels anxious.

Now that we’ve met the RED–BLUE mind model, we can understand what Tony is going through. Somewhere in his past, being late has led to some painful feelings. Perhaps it was being late on the first day of school. Maybe it was a combination of several occasions when he was late or cut it fine for sports practice and got yelled at by the coach, which caused him some embarrassment. These painful experiences have been long since buried among Tony’s unconscious memories. But today, as he sees he’s running late, a fusion of those painful memories and the feelings linked to them is once again automatically triggered by his RED system, which is primed to react to threats (whether real or imagined). No specific memory comes to mind, but the familiar feeling does. And so Tony’s anxiety system kicks in, and he ends up tense and anxious.

Turning up on time is a performance moment. No gold medals are at stake here, but being punctual is personally significant to Tony, while for others it’s not particularly important.

It goes to show that even apparently mundane, everyday events can carry a hidden performance agenda. And so when we enter an arena where the stakes are genuinely high, it should come as no surprise that our emotional reaction can skyrocket.

Think about this reaction as an unconscious, two-stage process. The first step is that old, painful feelings get automatically stirred up. The second step is that the feelings trigger an anxiety reaction to block those feelings from surfacing. These steps happen so fast that we usually only notice the second one – the anxiety reaction – which makes it seem like that happened first. But some people pick up a spike of emotion – perhaps a hot feeling surging up through their core – before the anxiety reaction comes in over the top to shut the emotion down.

Anxiety can make us feel tense or go flat if we hit our threshold, which can disrupt our thinking and senses. It can also cause a host of other physical sensations through our fight, flight or freeze reaction. But they’re different from the primary feelings of anger, guilt or grief. Anxiety is a secondary reaction.

The combined effect of the primary painful feelings and secondary anxiety is that we experience discomfort. This discomfort doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It comes about because of a process inside of us. And it isn’t random – it’s very predictable. We will get anxious in the same types of situation, again and again, when others do not.

Tony’s experience shows us that the common phrase ‘performance anxiety’ oversimplifies what actually happens inside our body. The external performance – being on time or not – activates Tony’s unconscious blueprint of feelings, which then trigger his anxiety.

The middle step is key. Though it usually happens so fast that we are not aware of it, it’s most definitely there, because otherwise, why would people react so differently to the same external situation?

As we’ve seen, external fear arising from real physical danger is hard-wired within us and is an automatic survival mechanism, driven by our biology. In brain terms, we react long before we can consciously think it through. And internally driven fear, or anxiety, is generated by our personal psychology. It’s not a genuine survival moment in the physical sense, although it is in the psychological sense: the anxiety is generated by doubt about our ability to mentally survive the occasion.

Although most performance situations don’t literally involve threat to our physical survival, it might threaten our psychological existence if we mentally live and die with our image and reputation. If we subconsciously frame these moments in survival terms, we will trigger survival responses.

The bottom line is that performance situations stir up deeply ingrained emotions held in our body, and anxiety in the form of tension can instantly lock things down, making us uncomfortable and affecting our ability to think clearly under pressure.

Performing under pressure usually means performing when we are uncomfortable.

Challenge: Going beyond threat

If our RED mind is primed for survival, our BLUE mind is primed for potential.

Safety comes first. If we are not safe, our RED mind is activated and dominates our thinking and behaviour. But once we are safe and the RED mind is calm enough, other opportunities open up. (It doesn’t have to be completely calm, just within the window of discomfort where you can still operate.)

The BLUE mind is well suited to looking at our immediate environment, solving problems and adapting. When we’re not forced to pay attention to getting out of a situation we don’t want to be in, our mental effort can be focused on creating a situation that we do want. In modern language, we call this goal-setting.

With its emphasis on language and logical analysis, our BLUE mind sees possibilities, nuances and opportunities by matching the current situation against prior experience. That’s how it evolved – as a creative, forward-thinking, adaptive mechanism. If the RED mind is the security at the door, the BLUE mind is the creative headquarters tucked safely inside, where plans are hatched and problems are solved.

When we engage our BLUE mind in pressure situations, a fundamental shift in mindset can occur: threat is replaced by challenge. Instead of trying to flee and bring the situation to an end as quickly as possible, our BLUE mind draws us towards the obstacle that’s in our way, using all mental resources at its disposal to adapt, adjust and improvise so we can overcome the challenge.

In a survival situation, there is a simple threat focus on outcomes such as living and dying, or winning and losing. With a challenge focus, our attention is drawn to the process of finding a way through. Judgment is replaced by movement. Instead of ‘Will I survive?’, the question becomes ‘How far can I go?’

If we regard the situation as a challenge, we’ll focus not on the outcome but on our capacity to deal with the demanding and difficult moments. Rather than a burden to bear, we’ll see the discomfort as stimulating.

Of course, with this challenge mindset, we will regularly fall short. But the key is in the method, not the outcome. What matters is our state of mind when we perform under pressure, not whether we succeed or fail. We don’t lose heart when we don’t meet the challenge, because we appreciate that the learning we’ve just experienced is precious. Moments of failure arguably create more opportunities to get better than moments of success. The critical step is to embrace the pressure situation in the first place.

No one can meet every challenge. If we do, then we’ve set the bar too low and the challenges we’ve set don’t really deserve the name.

To reach our full potential, we have to keep pushing ourselves to our limit and beyond. We have to put ourselves in a position to deal with more and more demanding tasks. It’s about full commitment to the moment.

This is more difficult than it sounds. The discomfort makes most people flinch, so they never fully test themselves.

The word test comes from the Latin testum, meaning an earthen vessel. The idea was that the vessel was used to examine the quality of a substance placed within it – like a test tube. Some material was put inside it and subjected to different conditions, like heat.

Our performance arena is the equivalent of a test tube. Our mind is the material inside it. And the condition we’re being subjected to is pressure.

Our personal properties are being deliberately examined under pressure. When we face the heat, what qualities do we display? How do we function as we approach our limit? Do we retain our resilience, or melt and lose our mental structure?

When we start approaching test situations with relish, our tolerance of discomfort increases. Don’t worry, you don’t have to actually enjoy the discomfort – you just have to appreciate what it achieves. Discomfort is not a punishment, it’s a testing moment we’ve earned, and an invitation to step up to the next level.

The big mental shift in performance under pressure comes when we can feel fear but accept deep inside that we will mentally survive the moment. Once the mental threat in a situation is contained, it loses its power to overwhelm us emotionally and shut us down, allowing us to re-energise and face the challenge.

A challenge mindset means feeling the discomfort, but facing down the challenge without flinching.

Alex, a freestyle skier competing at a big championship event, is about to start her second run after her first one ended in a fall. A second poor run would see years of hard work end in misery.

In that moment, Alex is scared. Not of falling, or of missing out on a medal, but of the shame she’ll feel when she sees her coach, parents and teammates afterwards. She feels empty inside. She’s facing psychological devastation. It’s a RED alert moment.

But she has prepared for this possibility. At precisely the instant when everyone else gives up on her and sees what she might lose, she sees an extraordinary opportunity and what she might gain: a comeback story for the ages.

She breathes in deeply and imagines energy filling her core, and as she breathes out, she pictures fire spreading heat and energy throughout her body. She stands tall and feels herself growing in power as others cower down. Nothing could be better in her mind: this is no longer a championship event to compete in, it is her championship moment to own. No longer empty, hollow and cold, Alex can feel the fire burning inside. Her confidence restored, she attacks the run.

Our mirror neurons – specialised nerve cells that allow us to pick up on how other people are feeling – allow us to feel the fear in others. And when we see people feel the fear but take on the challenge anyway, we are inspired. It is a signature moment for performance under pressure.

If we mentally flinch or fold, our performance will be compromised, but if we know we can survive this moment, we can take it on with relish. And much better to take it on with courage than to dither and stall. The true meaning of courage is to act with heart when you are scared.

We are not defined by pressure moments unless we let them define us. Move through and past the psychological threat to see the wonderful opportunity presented to us to go as far as we can. Instead of becoming mentally subdued, numb and frozen, we will come alive. It will be life-changing.

Reflect on your mindset when you hit discomfort. What’s your habitual response? Are you stimulated by the challenge of these moments, or does the threat loom larger? Do you walk towards them or walk away?

The discomfort of pressure: threat or challenge?

Overthinking vs Connecting

Overthinking

When I ask athletes to describe their worst 10 minutes in sport, one word always causes moans of recognition: overthinking.

It’s a strange word. Can we think too much, really? And are there particular thoughts that we can think too much about?

The athlete usually goes on to explain that they were trying their level best to right a wrong, or raise their game, but their best intentions backfired. The harder they tried, the worse things got. It even felt like there was pressure building up inside their head. They had too many thoughts, too fast, and it held them back.

Under pressure, elite sportspeople do not want to think too much or too fast, because it causes problems for their performance. A busy mind gets in the way of clarity. And that is universally seen as a bad thing.

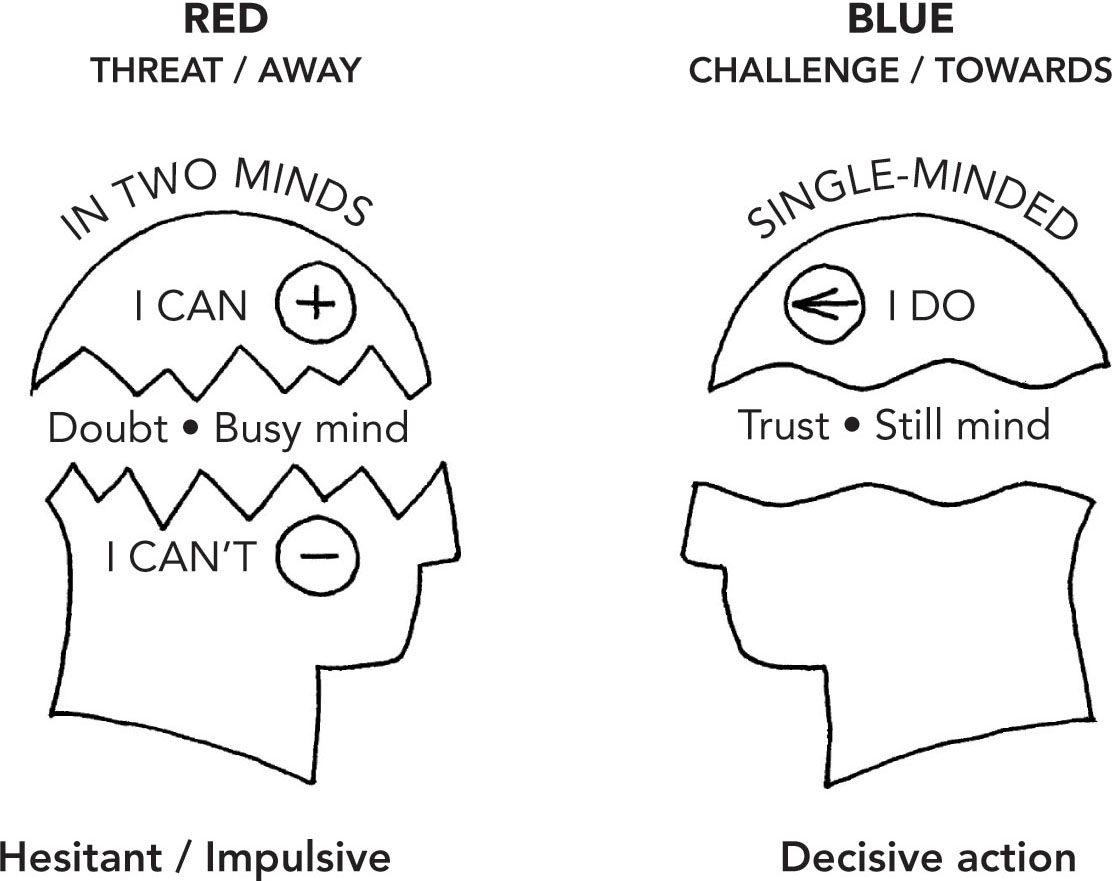

Imagine yourself in a high-pressure moment. Your confidence is taking a battering. The casual remedy is just to think positively, which assumes that we can just replace our negative thoughts with positive ones. But that is simply throwing fuel onto the RED fire.

Your BLUE mind is telling you: ‘I can!’ It’s not a particularly strong voice, perhaps even a bit squeaky. Because while it’s speaking there’s a far stronger, deeper, RED voice booming out the opposite message: ‘I can’t!’

It’s like having two independent minds going in opposite directions and arguing about which one is best. BLUE versus RED. And the RED message feels authentic, while the BLUE voice sounds hollow and unconvincing. (Remember, only our BLUE mind can use words; your RED mind speaks in the language of feelings and sensations. There are no words, but it certainly sends its message.)

In these situations, RED usually beats BLUE. The RED system will not lie down and be ignored – after all, it’s in charge of our survival. The survival parts of our brain appeared on the scene first and got prime position in our nervous system – right on the centre line, or close to it. The RED system cannot be switched off, and the harder the BLUE mind tries to suppress it, the louder the RED voice becomes. Every time we think something positive, a stronger negative thought or feeling comes bouncing back.

Mental chatter overloads our BLUE head, taking the top-down brakes off so that our RED head drives our behaviour more or less unchecked. RED is only interested in the here and now, so with the loss of our BLUE ability to read the play, our sense of direction and our awareness of possible consequences, we become prone to acting too fast, or too slow. That’s why we see even experienced performers become impulsive or hesitant in big moments.

RED vs BLUE STATE

When we are ‘in the RED’ we can lose emotional control, overthink and get diverted. When we are ‘in the BLUE’, we can hold our nerve, maintain our focus and stay on task.

Connecting

When I ask athletes to describe their best 10 minutes in sport, the one response that stands out is that they felt connected.

Instead of the overthinking that is the hallmark of their worst moments, their sense of connection with their immediate environment meant that they weren’t thinking much at all. Everything seemed so obvious and easy. They perceived, and they acted. They sensed, and they moved. They saw, and they did. The usual middle piece of thinking seemed to disappear. They were ‘in the zone’.

This intensely positive experience of connection is an example of complete absorption with our immediate environment. It’s when our connection with the external environment is so complete that we can effortlessly pick out small details that are overlooked by others, and act upon them decisively. It feels simple to get the timing right; in fact, time seems to slow down, allowing us to easily anticipate events and respond to them.

This is only possible when there’s no sense of disconnection. The most common disconnect occurs when we start to think not about how we are performing the task but how we are looking while we do it. We can only be completely on task when we lose our self-consciousness. The key is to commit all our attention to the external world, rather than splitting it between the external environment and a struggle within our internal world.

Instead of being distracted by doubt, we need to trust our ability to handle what is in front of us. This self-trust forms the RED backbone to support our BLUE focused attention. Banishing doubt and worry avoids overthinking – that busy mind that arises from an internal debate about what we’re doing.

But what about our discomfort, which we’ve seen is a key feature of pressure? We have to move through it. We can’t magically avoid or escape it, but we can choose not to focus on it. It just isn’t the main issue. We can make the discomfort an internal focus, leading to overthinking, with suffering in the foreground. Or we can simply notice the discomfort and let it subside into the background, while our focus returns to the immediate task. With this external focus on doing, our mind becomes still.

When our external environment is more captivating than our internal concerns, RED and BLUE can be in sync, which makes us feel single-minded as we go about our business.