Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

As a result of the Act, ten national parks have so far been established, of which the Peak District was the first. The others are the Lake District, Snowdonia, Dartmoor, Exmoor, the Pembrokeshire Coast, Brecon Beacons, the North York Moors, the Yorkshire Dales and Northumberland. Varying greatly in character and extent, these form a system having an aggregate area of nearly 4,750 square miles, or one-twelfth of the total area of England and Wales. This is surely an achievement which meets the long-felt needs of our highly urbanised people and which at the same time will secure large tracts of unspoilt country from inappropriate and unwarrantable forms of exploitation.

In Scotland the situation is different. The National Parks Act of 1949 referred only to England and Wales and no equivalent legislation has been passed for Scotland, except that the section of the Act dealing with nature conservation was made applicable to the whole of Britain. The Forestry Commission has nevertheless established a few national forest parks in Scotland, and although these have not the full status of national parks, they offer to the public increased facilities for access and open-air enjoyment.

The national parks of Britain differ from those of most other countries. To begin with, there are no large areas of wild scenery available for preservation like the huge National Parks of the U.S.A. or the great game reserves of Africa. Instead, the areas designated as parks are all of comparatively small extent and all are inhabited, even though the density of population in most cases is quite low. Again, the greater part of each national park is devoted to some form of economic activity such as farming, forestry and quarrying, thus creating problems of public access which seldom arise abroad. In every case in Britain the functions of a national park are added to an established pattern of economic and social life and must operate in such a way so as not to cause serious interference with existing activities. This circumstance naturally calls for much delicate negotiation in co-ordinating the various interests represented within a national park.

There is another important difference between our national parks and those abroad. Whereas the latter usually embrace truly natural scenery unmodified by human action, in Britain hardly any such areas remain. The land has been exploited by Man for so long that the results of his activities have profoundly altered the appearance of the surface. Even the natural vegetation has been greatly modified by various agricultural practices as well as by the chance or deliberate introduction of non-indigenous species. Forests have been entirely removed from some areas and have been created in others, while mining and quarrying have left their scars and debris on land once unspoiled.

In the sense that even our finest scenery, whether mountain, moorland or sea-coast, is in part the product of our cultural history, the national parks of Britain are of a rather special kind. In many respects the effects of long-continued human occupation signify a gain rather than a loss, for these effects tend to heighten the distinctive character of each designated area. Each national park bears the impress of its cultural history and this, taken in relation to the physical conditions gives it a high degree of regional individuality which it would not otherwise possess. It is for this reason that the national parks of Britain offer such impressive contrasts in landscape.

THE PEAK NATIONAL PARK

The upland region traditionally known as the Peak District, which forms part of the southern Pennines, has special claims to rank among the earliest of the national parks established in Britain. It was in fact the first to be designated, in December, 1950, although the Lake District and Snowdonia were included shortly afterwards. On grounds of the quality of its scenery alone its claim was irrefutable. The vast open moorlands which spread out from the massive summit of Kinderscout, the green dales of Dovedale and the Manifold Valley, the rocks and caves like those around Castleton and the glistening trout streams such as the Dove and the Wye, have long been enjoyed by large numbers of visitors from all parts of the country. Above all, The Peak has been cherished by the thousands of ordinary people, young and old, from the industrial towns of the Midlands and the North, who find recreation and adventure in the attractions it offers.

Like the National Parks movement as a whole, the promotion of such a park in the Peak District owes much in the first instance to voluntary bodies. Among these the Sheffield and Peak District Branch of the C.P.R.E. has been particularly active. More than any other body it was responsible for the idea in the first place, and from 1939 it has undertaken a great deal of pioneer work, including the preparation of a preliminary map of the boundaries. No less than ten thousand copies of the booklet entitled The Peak District a National Park, published in 1944, have been sold. Today, even though the Peak Park is now an accomplished fact, continued vigilance on the part of such bodies is perhaps more than ever necessary. An illustration of this is seen in the recent proposal to build a motor road along the Manifold Valley, a scheme which was happily defeated, again largely through the protests of the Sheffield C.P.R.E. supported by many other like-minded persons and societies.

From the standpoint of its geographical position the claim of The Peak to become a national park was particularly strong, for nearly half the population of England live within 50 miles of its boundary. Not only do the large cities of Manchester and Sheffield virtually adjoin it, but many other industrial centres of South Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Potteries are only a short distance away. Less than 60 miles away are Liverpool and the rest of Merseyside, while Birmingham and the Black Country, Leicester, Hull and Tees-side are all within 75 miles. Moreover, of all the national parks so far created, The Peak is the nearest to London and the most accessible from it by rail or road. The proximity to the park of such a large population has an important bearing upon its use by the public and hence upon problems of management. It can be approached from all directions and is frequented, at all seasons of the year, especially by people from the nearby industrial centres.

Popular claims to The Peak as an amenity area are further supported by the variety of interest which it offers to the more serious observer such as the naturalist, geologist, geographer, and archaeologist. The Peak is a part of highland Britain, yet is readily accessible from the lowland zone. As such, in its natural (including biological) features and its cultural forms, it exhibits elements of both environments. Its distinctive physical composition and its rich cultural legacy combine to form a regional complex with a character entirely its own. To both the week-end rambler and the holiday-maker with an inquiring mind the area affords a rewarding field for observation and study in the open air. To the naturalist in particular it is significant for its examples of true mountain and northern moorland habitats.

The attractions of The Peak have long been recognised by travellers from other parts. They gave rise to a literary cult rather similar to that inspired by the Lake District, though it may well have begun at an earlier date. In 1636 Thomas Hobbes, the philosopher and author of Leviathan, published his poem De Mirabilibus Pecci (Concerning the Wonders of The Peak), describing in ponderous hexameters the outstanding features of Derbyshire. Provided with an English translation in similar verse form, the poem became widely known and was reprinted several times in the next fifty years. Izaak Walton, whose delightful treatise The Compleat Angler (1653) offered pleasant instruction in the art of fly-fishing, shared with Charles Cotton of Beresford, with whom he pursued this quiet sport, a lasting affection for the Dove, the Wye and other Derbyshire streams. Though not accessible to visitors, the Fishing House overlooking the Dove, which Cotton built in 1674 to serve as an idyllic retreat, still stands. With their monograms inscribed over the door it bears witness to the long friendship between these two men. Cotton, besides being devoted to country pursuits, was influential both locally and in London and drew the attention of numerous friends to the scenic attractions of the Derbyshire-Staffordshire border, and in 1681 issued The Wonders of The Peak, a eulogistic poem much in the vein of Hobbes. Really in the nature of a guide, its true object is perhaps revealed by the fact that it was published in Nottingham and sold by the booksellers of York, Sheffield, Chesterfield, Mansfield, Derby and Newark, all of them places from which visitors might be expected to start their journeys into the region. Later on Celia Fiennes, a shrewd and observant traveller, describes in her Northern Journey, made in 1697, the route through Derbyshire, visiting each of the seven wonders in turn as if to do so were already the conventional tour. To the eighteenth-century writers, who almost invariably depicted the notable features of the area in exaggerated terms, six of the seven acknowledged wonders were natural features while the other was the Duke of Devonshire’s great mansion at Chatsworth. Its accepted place in the list is probably due to its inclusion by Hobbes as a compliment to his patron. Not everyone at this time held such favourable views, for Daniel Defoe in his Tour through Great Britain (1778) denounced Derbyshire as “a howling wilderness.” It was left to Edward Rhodes in the early nineteenth century, however, to establish for The Peak a lasting reputation as an area of beautiful scenery with many attractions for the tourist. His book on Peak Scenery (four volumes: 1818–23), splendidly illustrated by the artist and sculptor Sir F. L. Chantrey, R.A., who was a native of Derbyshire, was widely read and thus helped to make the area known to people from more distant parts of the country. The discovery of The Peak by visitors from outside was soon to be facilitated by the early railways. The new mode of travel brought the lovely scenery within reach of people belonging to all sections of the community, just as a century or more previously the fashionable spa at Buxton had attracted the well-to-do.

Recently, work by Mr. R. W. V. Elliott has revealed the existence of a literary association of a very different kind. By relating descriptions given in the text to actual topographical features, Mr. Elliott has shown that in all probability the Staffordshire portion of The Peak between Leek and Macclesfield, which now falls within the National Park, provided the setting for much of the famous medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The site of the castle of the Green Knight, to which Sir Gawain came, can be identified as that occupied by Swythamley Hall. Though the castle was evidently fictitious, Swythamley itself was certainly a hunting lodge in medieval times and came to be part of the endowment of the abbey of St. Mary and St. Benedict of Dieulacres near Leek, with which the origin of the poem may be connected. The Green Knight’s hunting grounds can be traced across the Roaches towards Flash and northwards beyond the headstreams of the Dane. The Green Chapel sought by Sir Gawain is doubtless the curious rock-chamber known to Dr. R. Plot, the seventeenth-century Staffordshire historian, as Lud’s Church and still named as such on present-day maps. (There is a tradition that the chapel served as a refuge for Lollards.) From the evidence it is clear that the author of Sir Gawain was not only minutely acquainted with this district but possessed a remarkable eye for detail and an exceptional capacity for precise description. It is to be hoped that further research will lead to a closer knowledge of the unknown poet of the fourteenth century whose work surely ranks with that of Chaucer.

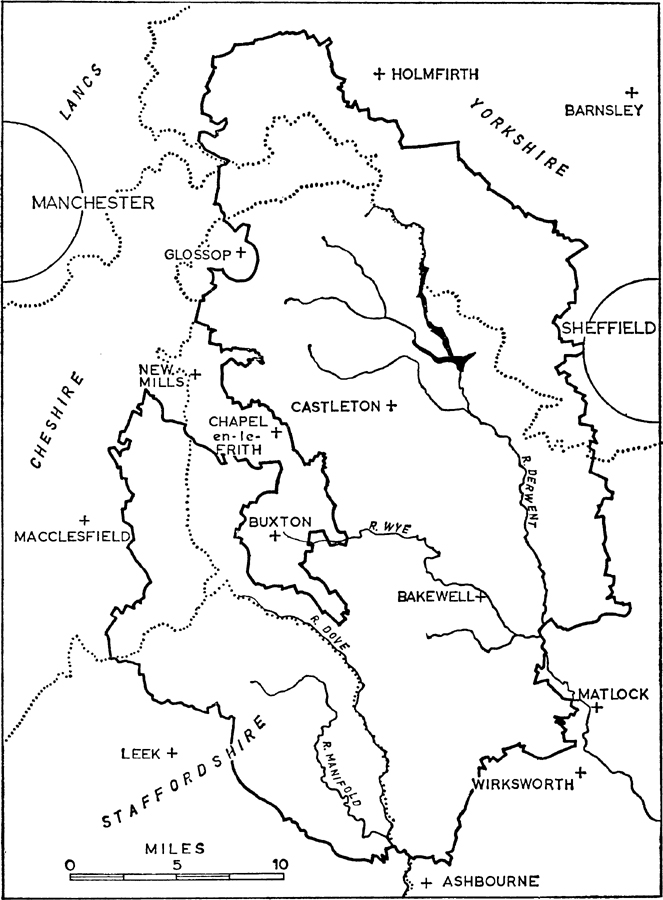

In size The Peak National Park, covering 542 square miles, is not so large as those of the Lake District and Snowdonia, though it is larger than any of the others. It occupies a considerable part of the county of Derbyshire, together with adjoining portions of Staffordshire and Cheshire to the west and the West Riding of Yorkshire, including a small area of the city of Sheffield, to the north (Fig. 1, opposite). Its greatest length from north to south is nearly 40 miles and its greatest breadth about 24 miles. The boundary which delimits the park would enclose a broadly oval shape but for the long narrow wedge reaching far into the interior from New Mills on the western margin to a point about five miles south-east of Buxton. This territory was excluded on the grounds of its predominantly industrial character; in it lie the towns of New Mills, Whaley Bridge, Chapel-en-le-Frith and Buxton, while around the last-named the landscape is seriously marred by intensive limestone quarrying and related lime-works. This feature has the effect within the Park of severing the High Peak of Derbyshire from the hill country of East Cheshire. On the south-east side for a similar reason, though without giving rise to a pronounced wedge, the Matlock and Darley Dale section of the Derwent valley was also excluded. On the south and west the towns of Wirksworth, Ashbourne, Leek and Macclesfield have all been omitted, though they lie only a little beyond the boundary.

Incidentally, two points concerning nomenclature should be mentioned here. In the first place, the term Peak District applies to the upland area of Derbyshire as a whole. There is no single mountain or summit named The Peak. The highest part of the area is in the extreme north where the two flat-topped moors of Kinderscout and Bleak Low both reach to over 2,000 feet. The highest point of all is on Kinderscout reaching 2,088 feet. Secondly, a distinction is sometimes made between the northern and southern parts of the upland. These are known respectively as the High Peak and Low Peak but the distinction is a vague one and is not based on altitude alone.

Fig. 1. The boundary of the Peak National Park

From the standpoint of administration the Peak National Park is managed by a central authority in the form of a Joint Planning Board consisting of 27 representatives, of whom 18 are appointed by the constituent county authorities and the county borough of Sheffield, and the remaining nine by the Minister of Housing and Local Government. The Peak Planning Board has its own technical department at Bakewell under the direction of a Planning Officer. This form of administration is the only example of the method originally envisaged for the national parks although in one or two other instances the form adopted approximates to it. On the whole in the case of The Peak it has worked successfully. Certainly, by excluding a number of urban centres situated on the fringe of the Park, general planning problems connected with the location of industry and urban growth and re-development have been considerably reduced, enabling the Planning Board to devote its attention more wholeheartedly to the special interests of the Park.

REFERENCES

PILKINGTON, J. A View of the Present State of Derbyshire (2 vols). (1789)

RHODES, E. Peak Scenery, or the Derbyshire Tourist. (1818)

GLOVER, S. The History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Derby. (1829–1833)

DOWER, J. Report on National Parks in England and Wales. H.M.S.O. (1945)

Report of the National Parks Committee. H.M.S.O. (1947)

Report of the National Parks Commission. H.M.S.O. (annually since 1950)

MONKHOUSE, P. J. Some National Park Problems. Jour. of the Town Planning Inst.: 43 (March, 1957)

National Park Guide No. 3: Peak District. H.M.S.O. (1960)

CHAPTER 2

THE ROCKS AND THEIR HISTORY

The hills are shadows, and they flow

From form to form, and nothing stands;

They melt like mist, the solid lands,

Like clouds they shape themselves and go.

ALFRED TENNYSON: In Memoriam

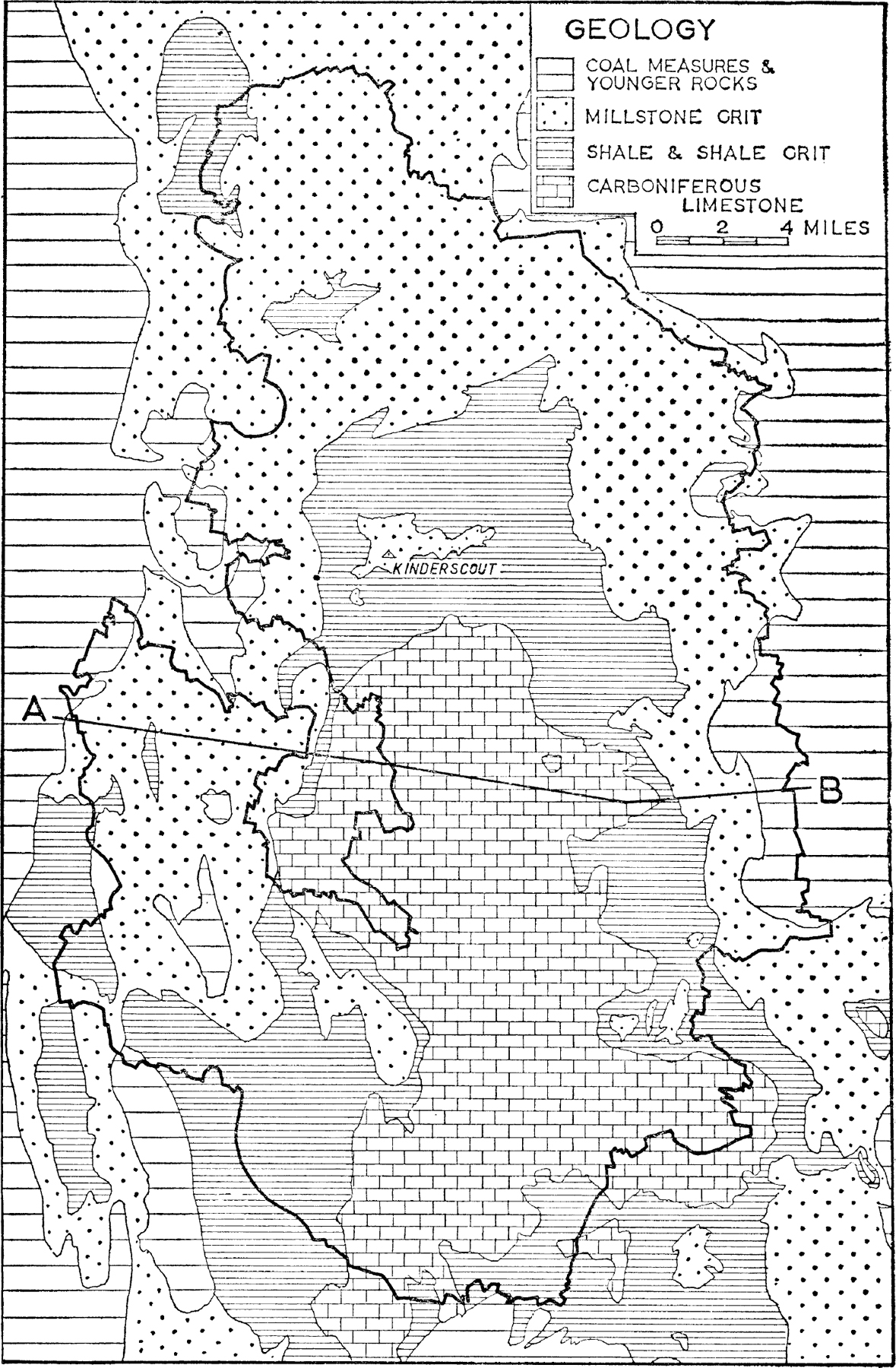

A WANDERER returning to his native village in the Peak District finds his favourite haunts unchanged. The dales and streams, cliffs, hills and moors are all just the same as they were in his youth. If, however, he has studied the rocks they tell him that this peaceful, enchanting scene is but an episode in a long and eventful story which moves so slowly that for the brief period of his lifetime it seems to have been at a standstill. His going and coming have been no more than the flicks of a fly’s wings. That story is recorded for him in the rocks of the district; in the limestone of the uplands on the south; in the grits capping the moorlands of the north and forming the ridges which girt the uplands on either side; and in the shales which underlie the fertile vales that lie between the areas occupied by these two types of rock (Fig. 2, see here).

THE FOUNDATION ROCK

The limestone teems with fossils which may be seen and collected wherever the surface of the rock has been washed by the rain for a long time or etched by weak acids seeping down from the covering of soil. These fossils are the remains of creatures that lived in an ancient sea which 280 millions of years ago occupied the whole district. How different was the outlook then! Blue sea extended to the horizon in all directions except the south where, in the offing, stood the miniature mountainous island of Charnwood which lay across the area now known as the Midlands. Its rivers were small and carried very little sand and silt into the sea, the waters of which were in consequence clean and clear. The sea was of no great depth and the scenery of its sunlit floor varied from place to place. Here and there were forests of stone lilies, animals that were allied to the starfishes. Each one grew upon a tall stalk built up of rings of lime piled one upon another to a height of eight or ten feet. The main body of the creature was at the top and carried five branching arms spread out like the fronds of a palm tree, to catch both the sunshine and the small organisms upon which it fed. When the stone lily died its flesh decayed and the fairy bead-like rings of the stalk and the limy framework of the arms and body fell to the floor of the forest and in the course of many generations built up deep deposits of calcareous debris.

Out in the open, beyond the bounds of the stone lily forests, lay coral reefs. These were produced by the combined activities of myriads of polyps. Superficially they resembled modern reefs but the structural details of the individual corals were strikingly different. Surrounding the forests and reefs were spacious wastes of mud formed from the shells and bodies of minute organisms which fell in a perpetual drizzle from the waters overhead. Burrowing in the mud or crawling over its surface were many worms and other creatures that fed upon the mud or caught the drizzle as it fell. These latter included lamp-shells, a type of animal that is scarce today but was then varied and numerous and played a much more important part in the economy of the sea floor. Like cockles and mussels their bodies were also enclosed in shells, often prettily shaped and ornamented. They were usually small shells but some were giants a foot or more in diameter.

Of special interest were certain curious molluscs belonging to the far-off ancestral stock of the Pearly Nautilus which lives today in the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Like this, they had shells which were divided into a succession of chambers separated by thin partitions. One large type is known as Orthoceras because its shell was straight and not closely coiled like that of the nautilus. Provided with a battery of tentacles round its mouth and with an apparatus for jet propulsion, it preyed upon fishes and other more peaceful creatures. The Goniatites were much smaller and their shells were closely coiled. In them the partitions between the chambers were folded, sometimes in sharp angles (gonia=angle) which suggested the name. These beautiful little creatures may be pictured as spending their days flitting or crawling over the coral reefs and browsing upon the coral polyps.

Fig. 2. Geology of the Peak District. A–B is the line of the section shown in Fig. 4 (see here)

The shells of all these animals added their quota to the deposits that were being laid down upon the sea floor. Nevertheless, though the sea was shallow, it did not become filled, for its foundations were subsiding at about the same rate as the deposits were accumulating. Thus it came about that they ultimately attained a thickness of nearly 2,000 feet.

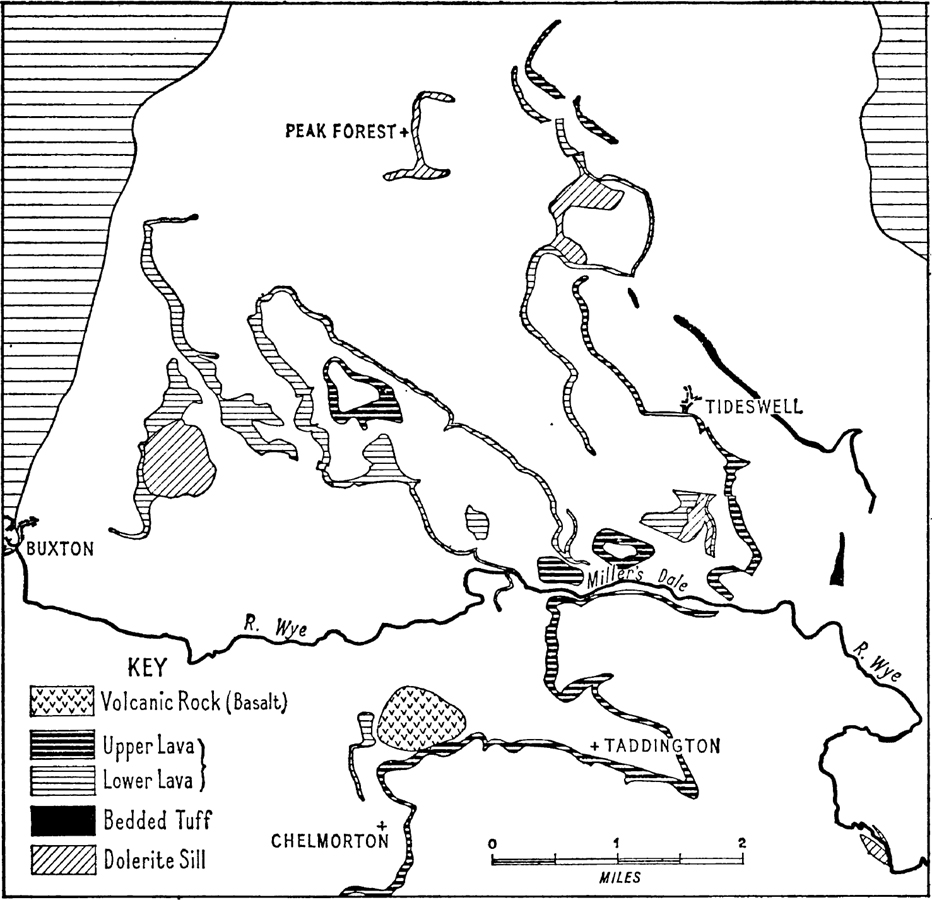

A temporary but fascinating feature in this submarine scenery was the occasional presence of small volcanoes. The ashes which they shot forth into the waters above settled down and became mixed with the mud beneath. Sheets of lava, full of steam bubbles, were poured out and flowed far and wide over the sea floor (Fig. 3, see here). The dark-coloured rock into which these lavas solidified is known as Toadstone and has a striking appearance due to the fact that the bubbles have been filled with a white mineral.

All the deposits described above consolidated and became the limestone which forms the Derbyshire upland. It is sometimes called the Mountain Limestone but to geologists it is known as the Carboniferous Limestone.

THE LATER ROCKS

The northern shores of the Carboniferous Limestone sea lay 200 miles away and stretched across the centre of the Scottish region. Scotland, at that time, was part of a great North Atlantic continent drained by large rivers flowing southwards. The general geographical picture thus presented was not unlike that of the United States with the Mississippi flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. These rivers carried the debris formed by the destruction of the uplands and by the rain washing the plains into the sea. Deltas of grit and sand were formed and banks built out along the shoreline. The fine muds were, however, carried farther afield and eventually reached the Peak District. Then for some time the sea-water was alternately clear and turbid, but eventually the latter condition prevailed. The mud accumulated and in course of time became those rocks known as the Edale shales which underlie the peaceful meadows of Edale and Darley Dale.

The fauna in the waters underwent a corresponding change. The stone lilies, corals and many of the brachiopods and molluscs departed from the area. A few of the last remained and were joined by other kinds of goniatites and bivalves. Meanwhile the deltas and sandbanks extended and began to invade the district from time to time. The quality of the water also changed from being saline through brackish to fresh. Marine animals disappeared and were succeeded by a less varied and sparse population. At first this included Lingula, a curious tongue-shaped brachiopod which had already existed for 250 millions of years from Cambrian times onwards, and was destined to continue in the world for a similar stretch of time until the present day. As the waters freshened still more, Lingula and its associates migrated elsewhere and were replaced by crowds of bivalves such as Carbonicola which resembled the mussel of the present-day rivers and canals. Towards the close of this phase in the story of the Peak District the occasional influxes of coarse sediments became more copious. Banks of grit and gravel were formed and ultimately became that massive hard rock known as Millstone Grit.

Fig. 3. Volcanic rocks occurring in part of the limestone of the Peak District. (Based on H. H. Bemrose)

Owing to slight oscillatory movements in the level of the region these deposits were sometimes raised above water level and produced a low-lying landscape of sandbank and water channels. Spores wafted by the breezes, seeds carried by the streams from the continent enabled plants of the northern continent to settle on this new land surface. In the warm moist atmosphere they quickly germinated and produced a jungle growth of fern-like plants and strange-looking trees. Of the latter the smaller ones resembled the Tree Ferns which now grow in the tropical forests of the East Indies. Others, known as Calamites, were closely related to the horse-tails, those tall weeds which look like miniature Christmas trees and today grow profusely in wet waste places. Some of the trees towered to a height of 60 or 80 feet and had trunks as much as five feet thick. The bark was often decorated with scale-like markings which suggested the name Lepidodendron (lepido=scale) for these trees. Their branches and twigs had a furry covering of small lancet-shaped leaves. The modern relatives of these trees are not to be sought for in luxuriant forests but on bleak moorlands where the Stags Horn Moss (Lycopodium) is to be found straggling through the grass. These plants do not grow from seeds but, like ferns, they reproduce by means of minute pollen-like spores.