Полная версия

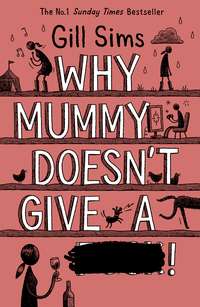

Why Mummy Doesn’t Give a ****

Peter wandered off back downstairs, in search of sustenance, and Jane burst furiously from the bathroom.

‘Is there a shower in the other bathroom?’ she demanded.

‘What other bathroom?’ I said.

‘There must be another bathroom,’ she insisted.

‘No, darling, there’s only one bathroom, I’m afraid. That’s sort of the thing about downsizing. You have a slightly smaller house. The clue is somewhat in the name, you know.’

‘But there must be another bathroom. An en suite or something. That can’t be the only one.’

‘It is,’ I informed her, as her face fell.

‘But there’s no shower,’ she wailed. ‘How am I supposed to wash my hair?’

‘Well, in the bath, sweetheart. Like people did for hundreds of years before the Americans invented showers.’

In truth, I’m not 100 per cent sure whether Americans invented showers or not, but it sounded plausible as they invented most mod cons. Luckily Jane was too distraught to challenge this statement, which made a nice change, as she usually likes to query every single thing that I say.

‘I can’t,’ she whimpered. ‘It’s not possible. I’m not THREE, to have plastic cups of water sluiced over my head, Mother! This is awful. Are you SURE you don’t have an en suite you’re hiding from me?’

‘Why would I hide an en suite from you?’ I said in surprise (though in truth, as I looked around the dimensions of the cottage, which could at best be described as ‘bijou and compact’, there was a small part of me also hoping for some extra rooms to materialise from somewhere, like the splendid room full of food the Railway Children found the morning after moving into their own slightly less than dreamy cottage).

‘I don’t know. I don’t know why you do anything anymore, Mother. You’ve abandoned Dad, you’ve made us come and live in this dump, and all you offer us in return is wittering on about how we’re going to get chatty chickens. So I wouldn’t put it past you to hide an en suite from me,’ she said bitterly.

‘That’s so unfair,’ I said. ‘I haven’t abandoned anyone.’ I bit back my words as I was about to snap, ‘Your father was the one who moved out, if you recall, not me. He was the one needing his “space to think”, not me. I’m the one who’s always here for you.’ But I managed to stop myself in time, as my mother’s voice rang in my ears, saying those exact things to me, reminding me how she was the victim and encouraging me to take her side. I would not have my daughter see me as a victim, and I would not, even if it killed me, say anything to make her feel she had to choose between Simon and me. The only reason I’d managed to stop myself telling the children about Miss Madrid was to avoid making them pick sides. Tears pricked in my eyes at the sheer injustice of it, though, that the more I tried to be fair and not make them take sides, the more Jane raged and hated me and blamed me for everything. Luckily she’d stormed off to find something else to complain about before she saw the treacherous tears. I wiped my eyes and sniffed ‘Strong Independent Woman’ to myself, as Peter bellowed up the stairs, ‘MUM! There’s TWO rooms with sinks down here, so how do I know which one is the kitchen?’

I trudged downstairs to explain to Peter in words of ideally less than one syllable that the BIG room with the fridge, cupboards and table was the KITCHEN, and the very small room beside the back door with nothing more than a sink in it was the SCULLERY. There then ensued a lengthy discussion about what exactly a scullery was, culminating in Peter saying, ‘Well, if it’s just a utility room from the olden days, why don’t you just CALL it a utility room?’ and me insisting, ‘Because this is a lovely, quirky, quaint old cottage, darling, with oodles of character and they have sculleries, not utility rooms. It’s all about the soul, you see,’ while Peter shovelled Doritos into his mouth and look at me in confusion.

‘OK, Mum,’ he said kindly. ‘We can call it a scullery if it makes you happy.’

I was so nonplussed at winning the scullery battle so easily, and fretting that it was because Peter felt sorry for me (in the old house, everyone but me had persisted in calling the larder ‘the big cupboard’ despite my frequent exhortations to call it ‘the larder’ because we were more middle class than a ‘big cupboard’), that I forgot to take the Doritos off him before he inhaled the entire bag.

He was still cramming fistfuls of Doritos into his mouth when Jane marched downstairs and announced that she supposed she’d just have to make do with having a bath, and where were the towels? I suggested that perhaps she could help with the unpacking for a little longer before buggering off to bathe herself, but was frostily informed that this wasn’t an option and her life had been ruined quite enough. I replied that maybe, just maybe, if she’d shown the TINIEST bit of interest in her new home, the lack of bathrooms and showers would not have come as such a shock to her, but this was met with an eye roll and a snort. I counted myself lucky to have avoided a ‘FFS, Mother!’

I’m still trying to pinpoint when the ‘Mothers’ began. When she started talking, Jane would call me Mama, which was too bloody adorable for words, then when she was about three and a half, a horrible older child at nursery made fun of her for saying Mama, and she switched to Mummy. Then it became Mum, but it happened gradually, so I don’t really remember when exactly she gave up on Mummy, although it didn’t really matter, because Mum was OK, and anyway, only screamingly posh people with ponies called Tarquin (both the people and the ponies) still call their mothers Mummy past the age of about twelve. But I was quite unprepared for the day when I stopped even being Mum and simply became Mother – a word only uttered when dripping with sarcasm, disgust, condescension or all three. To my shame, I think I vaguely recall a time in my teens when I also only referred to my dearest Mama as Mother in similarly scathing tones, so I can only hope it’s just a ‘phase’ and that she’ll grow out of it. Though I’m wondering how many more fucking ‘phases’ I have to endure before my children become civilised and functioning members of society.

It seems like people have been telling me ‘It’s just a phase’ for the last fifteen bloody years. Not sleeping through the night is ‘just a phase’. Potty training and the associated accidents are ‘just a phase’. The tantrums of the terrible twos – ‘just a phase’. The picky eating, the back chat, the obsessions. The toddler refusals to nap, the teenage inability to leave their beds before 1 pm without a rocket being put up their arse, the endless singing of Frozen songs, the dabbing, the weeks where apparently making them wear pants was akin to child torture. All ‘just phases’. When do the ‘phases’ end, though? WHEN? I’m surprised, when every man and his dog was sticking their nose in and giving me unsolicited advice about what to do about my marriage (‘Leave the bastard,’ ‘Make it work for the children,’ ‘You have to try and forgive him,’ ‘Screw him for every penny he has,’ ‘You have to understand that it’s different for men,’ ‘Cut his bollocks off’), that no one told me that shagging random women in Madrid was obviously ‘just a phase’, and I just had to wait for Simon to grow out of it.

‘MOTHER,’ shouted Jane, bringing me back to earth with a bump. ‘You still haven’t found me a towel.’

‘Jane,’ I said as calmly as possible. ‘If you want a bath that badly, you’ll have to find your own towel. I’ve other things to do.’

Peter mumbled something unintelligible through a mouthful of Doritos, spraying orange crumbs all over Jane.

‘OH MY GOD! HE’S DISGUSTING! MOTHER, DO SOMETHING ABOUT HIM!’ screamed Jane. ‘Can’t he, like, live in the shed or something?’

Peter swallowed, and in the brief window before eating something else shouted, ‘YOU live in the shed! Live with the CHICKENS! Ha ha ha!’

Jane screamed more and Peter continued to snigger through his mouthful of salty preservatives and flavourings, and I left the room in despair. I decided to unpack my books. That would be a nice, calming activity. And also, once the books were on the bookcase, they’d hide the large and extremely dubious stain on the floral wallpaper that had looked so charmingly faded and vintage a few months ago, and now just looked like something from the ‘before’ shots on Changing Rooms. Maybe, I mused, as I stacked the books, I could strip off all the paper and do something cunning with bits of baton to give the impression of wood panelling, à la Handy Andy …? Then I found Riders and decided to cheer myself up with a few pages, for surely there’s no situation so dire, especially not when it comes to cheating men and revolting teenagers, that has not been faced up to by one of Jilly Cooper’s characters with a large vodka and tonic and an excellent pun. Jake was just shagging Tory in the stable for the first time, and I was wondering if I too looked a lot less fat without my clothes on – I suspected not, though the horrible realisation was dawning on me that if I were ever going to have sex again, I would HAVE to take my clothes off in front of a strange man, although to be honest, the thought of just never having sex again was preferable to doing that – when a drenched and furious Jane shot into the room, making noises like a scalded cat. The problem, it quickly turned out was quite the opposite – she was very far indeed from being scalded, because having run herself a nice deep bath, she’d plunged in to find that it was freezing cold, because there was no hot water.

‘Oh, I expect they’ve maybe just turned it off, in case the pipes freeze or something,’ I said vaguely.

‘It’s APRIL, Mother,’ said Jane. ‘The pipes won’t freeze in April! And anyway, they only moved out yesterday, you said. Why would they turn off the hot water for the twenty-four hours before we moved in?’

I’d no idea, but I wasn’t giving Jane the satisfaction of saying so. I poked vaguely at the boiler, hindered rather than helped by Peter, who insisted that if I’d just let him look at it, he could probably fix it. I wasn’t sure if he was trying to be helpful or just taking after his father, who always claimed he could fix things and refused to call a professional in until after he’d broken it even more.

‘What’s for dinner?’ demanded Jane, as I hopefully pressed all the switches and turned the boiler on and off several times.

‘Oh God, I don’t know, I’m trying to fix the boiler,’ I snapped.

‘I only asked. Don’t we even get fed now?’

‘Jane, you’re fifteen, you can make yourself something to eat. I’m trying to fix the fucking boiler right now.’

‘Can I go to Dad’s? I hate it here, I want you to drive me to Dad’s.’

‘I’m not driving you to your father’s because I’m trying to fix the boiler and if you want to go there so badly, call him to come and get you.’

‘He didn’t pick up. So you need to take me.’

‘I don’t need to do anything, except fix the boiler.’

‘You NEVER do ANYTHING for me. I bet if Peter wanted to go to Dad’s you’d take him.’

‘I’m not taking anyone anywhere. This is our first night in our new home and it would be nice if we spent it together. Now please give me peace while I try to fix the fucking boiler. PLEASE!’

‘Mum, when will the Wi-Fi be connected? Can you call them and find out?’ said Peter.

‘I’M TRYING TO FIX THE BOILER!’

‘When can you call them, then?’

I kicked the scullery door closed and leant my head against the piece of shit broken boiler. I was only one person, trying to do the job of two. At least if Simon had been here, he could have been the one swearing at the boiler while I dealt with the children’s incessant demands for food, lifts and internet access. But Simon wasn’t here, I reminded myself, as those tears threatened again, and I wasn’t going to be beaten by a bloody boiler. I could do this. I gave the boiler a tentative whack with a wrench. It had not responded to me hitting it with a pair of pliers, but I was working on the basis that boilers came under plumbing and wrenches were plumbing tools and therefore it might work better. I was quite proud of my logic, but the boiler remained stubbornly lifeless. Finally, I had one last idea before I spent the GDP of Luxembourg on an emergency plumber. I stumbled out to the oil tank (too country for gas) and, by the light of my phone torch, found a valve on the tank that looked suspiciously like it was pointing to ‘closed’.

‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained,’ I muttered, as I barked my shin on a stupidly placed piece of wall, and turned it to open. Either the boiler would burst into life, or I’d burn the house down. I went back inside, stubbing my toe on an abandoned plant pot and surveyed the boiler once more. It still sat there lifeless. I went through the process of pressing all the buttons again, and miraculously, on pressing the reset button, it finally roared into life. I’D DONE IT! I’D FIXED THE FUCKING BOILER!

‘MUUUUM!’ yelled Peter.

‘MOTHER!’ howled Jane.

I flung open the scullery door in triumph.

‘I’VE FIXED THE BOILER!’ I announced, expecting at least a fanfare of trumpets and a twelve-gun salute. ‘I was right, Jane. They had turned it off. Outside!’

Jane snorted. ‘I bet Dad would have known that hours ago.’

‘I didn’t need a man, I fixed it myself.’

‘Whatever. Can I go to Millie’s?’

‘NO! We’re going to have a lovely night together. I’ll light the fire and we’ll have a picnic dinner in front of it.’

‘Isn’t this fun?’ I said brightly later on, sitting with Judgy Dog before the rather smoky fire.

Jane snorted from beside the window, where she’d discovered an intermittent 4G signal.

‘It’s quite fun, Mum,’ said Peter carefully. ‘But it would be more fun with Wi-Fi, if you could phone them in the morning and see when we’ll get the broadband connected?’

The fire went out.

Judgy made a snorting noise rather akin to Jane’s, and something scratched suspiciously behind the skirting boards.

‘It’s fun,’ I said firmly. After all, as the saying goes, sometimes you just have to fake it till you make it.

Saturday, 14 April

My first weekend here without the children. In fairness, Simon had offered to take them last weekend so they were out of the way while I moved, but foolishly I’d laboured under the impression that they were old enough and big enough to make themselves useful – I’m nothing if not an eternal optimist …

Last week passed in a blur of desperate attempts to find work clothes from the general jumble of boxes, days at work mainly spent lining everything up on my desk in beautiful straight lines and appreciating the general tidiness and order of the office, before returning home to demand what the children had been doing all day (lounging around, eating and making a mess – such are the joys of teenagers in the school holidays), stomping round shouting about the mess the children had made, hurling the trail of plates and glasses left around the house in the dishwasher, and bellowing about who had drunk all the milk again, before spending the evenings in a whirl of unpacking boxes, wishing I could go to bed because I was knackered, feeling somewhat overwhelmed by the sheer number of boxes needing to be unpacked and wondering why the fuck I’ve so much stuff.

When Simon and I first moved in together, every single thing we owned in the entire world BETWEEN US fitted in his rusting Ford Fiesta, with room left over. Over twenty years later, and it took two vast removal lorries to distribute our possessions, not to mention the skip full of crap, the innumerable bags to the charity shops and several runs to the local dump. I’d packed everything up in a tremendous hurry, flinging things into boxes and promising myself I’d sort it all out at the other end (this rushed packing also led to some raised eyebrows from the removal men as they looked askance at my boxes labelled with things like ‘kitchen crap’, ‘general crap’ and – this was one of the last boxes I packed – ‘more fucking shit’), but this was proving harder than I thought, as I pulled out Jane’s first baby-gro – so tiny, and rather faded and yellowing now, but even so, I couldn’t possibly get rid of it.

I had rather a lump in my throat, when I found a box of photos of me in hospital holding a newborn Jane in the same baby-gro, Simon beaming proudly beside me. These must have been some of the last actual photos we ever took, before we got a digital camera. Beneath the box of photos were red books filled with their vaccination records. Did I need them? What if at some point they needed to prove they had been vaccinated? Would that ever happen? I set them to one side in the ‘maybe keep’ pile, and then I found Peter’s first shoes. So tiny! I remembered the day we bought them. There should be a photo of that too – I dug through the box, and there it was, a Polaroid taken by Clarks of a small, furious and scowling Peter, clutching his blanky, who had been unimpressed with this momentous day. Did he still have his blanky, I wondered? We’d gone to the park after he got his shoes and he’d been so pleased with himself as he tottered across the playground on his own for the first time, me hovering anxiously by his side, ready to catch him if he fell. The shoes were definitely for the ‘keep’ pile. And what was this? A box full of tiny human teeth? Well, of course I was keeping that, even if at some point the children’s teeth had got jumbled up and I no longer knew whose were whose.

Jane wandered in at that point. She looked at my little box of teeth that I was gazing at fondly and said, ‘You do know, Mother, that one day you’re going to be dead and we’re going to have to clear your house out and it’s going to be like totally gross if we have to come across things like boxes of human teeth.’

‘But they’re your teeth,’ I protested. ‘It’s not like I’m a serial killer and I’ve kept the teeth of my victims as a souvenir. They are keepsakes from your childhood.’

Jane gave another one of her snorts. ‘It’s still gross,’ she insisted. ‘In fact, it would be less weird if you had killed people for their teeth. Why do you have them?’

Once upon a time, that special moment had been quite magical, when Simon and I first tiptoed into Jane’s room, as she lay there, all flushed and rosy-cheeked in her White Company pyjamas, sleeping innocently, dreaming of the Tooth Fairy and the spoils she’d wake up to. We slid a little pearly tooth out from under her pillow and popped a (shiny shiny) pound coin in its place. We stood hand in hand and gazed down at her, still slightly in awe of this perfect little person we’d made together. We put that tiny little tooth into the special box I’d bought for it, and marvelled at how grown up our baby girl was getting. I wondered if Simon and I would ever do anything together again like that for the children?

Of course, the standards slipped in later years – any old pound coin would do – and quite often I’d forget, and when an angry child burst into my bedroom complaining the Tooth Fairy hadn’t been I’d have to hastily rustle up a pound coin and pretend to ‘look’ under their pillow before triumphantly ‘finding’ it, and accusing them of just not looking properly. Luckily they fell for this every time, and I still constantly complain about them never looking for anything properly. Now though, looking into the box filled with yellowing little teeth, several of them still bearing traces of dried blood where, the sooner to get his hands on the booty, Peter had forcibly yanked them out, it did seem a rather macabre thing to keep. But on the other hand, a) I wasn’t actually going to admit that to Jane, and b) I’d really gone to rather a lot of effort to collect those teeth and so I wasn’t quite ready to part with them just yet. Anyway, they might come in useful for something.

‘Useful for what?’ said Jane in horror. ‘Seriously, Mother, what exactly do you think a box full of human teeth might be useful for? Are you going to become a witch or something? Eye of newt and tooth of child? Is that why you’re getting chickens – you claimed it was because they were chatty, but actually you’re planning on sacrificing them and reading the portents in their entrails while daubed in their blood? I’m not having any part of that. I’m going to go and live with Dad if you do that. That’s just going too far, Mother.’

‘What?’ I said in confusion. ‘How did you get from your baby teeth to me becoming some sort of chicken-murdering devil worshipper? I’m not going to sacrifice the chatty chickens. The chickens aren’t even here yet and you’re accusing me of secretly wanting to kill them!’

Simon chose that moment to arrive and collect his darling children.

‘Dad, if Mum becomes a Satanist and kills the chickens, I’m coming to live with you, OK,’ Jane informed him by way of a greeting.

‘Errr, hello darling,’ said Simon. ‘Why is your mother becoming a Satanist?’

‘I’m NOT,’ I said crossly.

‘She collects human body parts,’ said Jane darkly.

‘I BLOODY WELL DON’T!’ I shouted.

This wasn’t the scene I’d envisioned for Simon seeing me in my new home for the first time. I’d lost track of time, and instead of being elegantly yet casually clad in a cashmere sweater and sexy boots, perhaps with some sort of flirty little mini skirt to remind him that actually my legs really weren’t bad still, while reclining on a sofa in my Gracious Drawing Room, I was in my scabbiest jeans, covered in mud from walking Judgy earlier, with no make-up, dirty hair and clutching a box of teeth, with the house looking like a bomb had gone off and boxes everywhere. Simon meanwhile appeared to have finally cast aside his scabby fleeces in favour of tasteful knitwear and seemed to be attempting to cultivate some sort of designer stubble. Or maybe he just hadn’t bothered to shave. Either way, it suited him. Bastard. I glared at him.

‘Right …,’ he said, wisely deciding the best thing to do would be to ignore this whole conversation and pretend it had never happened. ‘Jane, are you ready? And where’s your brother?’

Jane looked surprised. ‘Ready? What, now? Like, NO, I need to pack. How should I know where Peter is? I’m not his mother!’

I sighed. ‘I suppose you’d better come in then, Simon. Would you like a cup of tea?’

‘Could I get some coffee?’

‘Fine.’

At least the kitchen was unpacked and relatively tidy. I reached for the jar of Nescafé, as Simon said, ‘Don’t you have any proper coffee? You know I don’t like instant coffee.’

I gritted my teeth. ‘No, Simon. I don’t have any proper coffee, because I don’t have a coffee maker, because I don’t drink coffee, and so I only have a jar of instant as a courtesy for guests, and I only offered you a cup of tea in the first place because I’m trying VERY HARD to keep things between us on an amicable footing, at least on the surface, so we don’t mentally scar and traumatise our children and condemn them to a lifetime of therapy because we weren’t adult enough to be civil to each other, but I must say, you’re doing an extraordinarily good job of making it difficult for me to FUCKING WELL DO THIS!’

‘You don’t drink coffee?’ said Simon. ‘Since when don’t you drink coffee?’

‘I haven’t drunk coffee in the house since I was pregnant with Jane,’ I said. ‘I occasionally, VERY occasionally have a latte when I’m out, but other than that, I barely touch the stuff, because it made me puke like something out The Exorcist when I was pregnant. How have you never noticed me not drinking coffee over the last FIFTEEN YEARS?’

‘But what about the coffee maker I gave you for your birthday a few years ago?’

‘Would that be the coffee maker when I said, “Well, this is a lovely present for you, because I DON’T DRINK COFFEE?”’

‘I thought you were joking. Is that why you let me keep it?’

‘Yes, Simon. Because there’s no point in me having a shiny fuck-off coffee machine cluttering up my kitchen when I DON’T DRINK COFFEE! Are you starting to perhaps grasp why we’re getting divorced?’