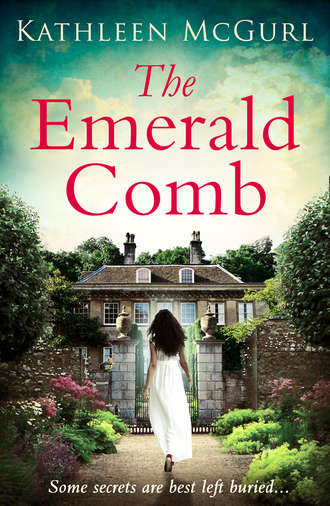

The Emerald Comb

Полная версия

The Emerald Comb

Жанр: книги по психологииисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературазарубежная психологиясерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу