Полная версия

Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia

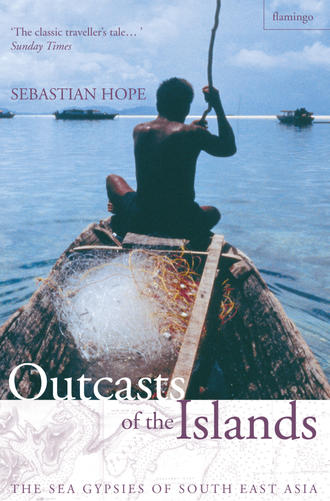

Out in the channel, the sun was fierce. We passed the stilted suburbs of Semporna, single plank walkways their pavements, the open water between buildings their streets. Pump-boats putt-putted in and out of the maze, small two-stroke in-board engines making them sound like mopeds, their riders sitting at the stern with one arm hooked over the plywood side working the paddle that acted as the boat’s rudder. Their flat plywood bottoms bounced across the wake of a trawler coming into port, nets furled around the davits. Less than a mile away was the coast of Bum Bum, with villages dotted amongst the coconut plantations, clusters of rusting roofs surmounted by the shining tin dome of a mosque. The channel turned and broadened, habitation becoming more sparse, and ahead was open sea. Flying fish fled our bow wash.

As we cleared Bum Bum’s southern point, the stilt village that had appeared to be attached to land turned out to be freestanding, planted on pilings over a shallow reef, the houses connected to each other, but to nowhere else. Behind was another island, Omadal, inhabited, and a Bajau Laut anchorage. I scanned the horizon off the port bow where I thought Mabul should be, and I made out a low regular shape looking like the cap of a mushroom, the sides curving down and in on themselves, the top flat – the characteristic shape of a coconut plantation. Sarani moved over to where I sat.

‘That’s Pulau Mabul,’ he shouted, pointing to the shape. We were still travelling south-south-west along the coast, and Mabul was due south, which left me wondering about our course.

‘We are not going that way?’ I pointed straight out towards it.

‘Cannot. There’s coral, you see?’ I had not been looking properly, but now I could see a line of grey rocks that broke the water, the palisade of the Creach Reef running uninterrupted from Bum Bum to the group of three islands we were approaching. ‘Only at the top of the tide can we go that way.’ He looked round at an estuary that bit into the mainland. The river brought brown water and forest leaves out into the channel. The mudflats were uncovered between the mangroves and the water line, and as we passed, a view into the inlet opened up, its banks covered in nipa palm; behind, were hills rising to one thousand feet and the westering sun. Sarani pointed to the flats where egrets stalked. ‘The tide is still coming in. We must go around these islands to reach the deep water.’ He pulled a dirty Tupperware box from under the gunwale, his betel-chewing kit. He peeled off the husk, mottled orange and black, divided the nut and wrapped a portion with some powdered lime in a leaf. He stuffed the package into a metal cylinder which fitted over a wooden baton and mashed the nut and leaf and lime into a paste with what looked like an old chisel bit. He pushed the cylinder down and the baton, acting as a plunger, presented a plug of pan to Sarani’s reddened lips. He packed away the paraphernalia, and went back to scanning the sea, spitting pensively over the side. It is a complicated business, using a masticatory when you haven’t got any teeth.

Manampilik, the last of the three islands, was little more than a steep ridge with a rocky shore. Coconut palms clung to the lower slopes, the higher left to scrub. The sea was glassy in its shelter. There was a swirl at the surface. ‘Turtle,’ said Sarani, and as I looked for it to show again, a fish as thin as an eel, a long-tom, broke from the water ahead of the bow and skipped like a stone once, twice, three, four times, each leap carrying it ten feet. The run ended only after another ten feet of tail-walking. I had never seen anything like it. Sarani laughed at my surprise and said, ‘They taste good.’

We rounded the southern edge of the Creach Reef and passed in deep water between Manampilik and a fourth island, confusingly called Pulau Tiga, ‘Third Island’, a tiny islet, no more than a sand bar, yet covered with stilt houses. It seemed the most unlikely place to site a village, on a strip of sand that looked as though it would wash away in a big sea, with nowhere to grow anything, no fresh water. Was there even any land left at high tide?

‘Oh yes, there is still land,’ said Sarani, ‘you see, they have trees.’ And there were two forlorn papaya plants, whose sparse crown of leaves on a long stem poked up between the roofs, growing in the middle of the village. There was a volleyball net strung between them. It was a surreal touch on a surreal island, a sand bank in the middle of nowhere that quadrupled in size twice a day. Sarani had family connections here. One of his sons had married a girl from the Bajau Laut group whose boats I could see anchored on the southern side of the island. It was my first glimpse of a Bajau Laut community, and it thrilled me.

We turned east-south-east, away from the mainland, and the horizon became immense. The water was indigo, marbled with wind lanes, and moved with a slow rhythm from the south, from the vastness of the Celebes Sea. I could see the tops of the trees on Sipadan to the south-east, the ragged outline of its tiny patch of rain forest, and due east, the peak of Si Amil. Danawan, separated from Si Amil by a narrow strait, and Ligitan, the last island in the group, remained hidden below the horizon. Sailing east from Ligitan there is nothing but water for the next five hundred miles.

We slowed as we approached Mabul’s fringing reef and picked our way through the coral heads, Sarani sitting in the bow on the look-out for snags. The evening sun threw a warm light over the stilt village on the southern shore and long shadows in the grove of palms behind. The shouts of children playing came out across the water. Pump-boats and brightly painted jongkong were returning with the day’s catch, being dragged up the beach between the houses. We made for a long barrack-like building – the school – and nearby a fence ran back into the palms, marking the end of the village, and the beginning of the Sipadan-Mabul Resort. The stilt houses connected to the beach by duck boards were replaced by sun-chairs and thatched umbrellas. The resort’s liveried jongkong and speedboats, all bearing the ‘SMART’ logo of a turtle kitted out in scuba gear, were pulled up on the raked sand. Set back amongst the palms were bungalows with verandas and air-conditioning units. It was a different country.

Sarani expected me to get off here and stay in the resort. He had not completely understood what I wanted to do, and now that I was on the boat I certainly did not want to get off it. ‘You cannot stay on the boat tonight,’ he was adamant, ‘but we will come back for you in the morning. Maybe you can stay in the village.’ We motored around to the other side of the island where the houses were poorer, more ramshackle, and dwarfed by an orderly group of wooden buildings at the end of a long jetty – another resort, the Sipadan Water Village. We nosed back in over the reef, and towards a house whose seaward wall had a doorway where sat an old man with a grizzled crew cut, shirtless, watching our progress. Sarani hailed him, as we cut our engine and glided in, the bow poking into the woven palm-leaf wall. It was agreed. My bags were passed into the house, and Sarani signalled for me to follow them. I clambered in.

‘Until tomorrow?’ I said.

‘Until tomorrow, early.’ I watched him pole the boat around and out towards the deeper water, the sun setting behind the hills on the mainland. I was not completely sure if I would see him again. Meanwhile, for the second time that day, I found myself landed in a strange world where I was the strangest thing in it, feared by the children and stared at by the adults, talked about in a language I did not understand. I sat with my luggage on the other side of the seaward door from the old man. His family hemmed us in, their curious faces catching the last of the light from the western sky. Shadows grew from the back of the hut’s single room. Fishing lines, nets, clothes hung from the palm-thatch walls, baskets from the rafters. Woven pandanus mats and pillows lined one side. I looked around while they looked at me. I looked out at the strands of painted clouds above the silhouette of the mainland, the sea turning grey in the twilight, lights coming on in the resort. Noises of the village relaxing in the dusk, the smoke of cooking fires came from the landward. Wavelets broke on the beach. A breeze rustled in the thatch eaves and set the palm trees soughing. ‘It’s very beautiful,’ I said to the old man in Malay.

‘Jayari cannot speak Malay,’ said Padili, his youngest son, ‘but he can speak English.’ I repeated myself and Jayari followed my gesture at the horizon with his eyes, still uncomprehending. He saw only what he had seen every day of his life, the sea that supported him and his family, the sea that kept them poor. And not a hundred yards away was the Sipadan Water Village, a faux primitif mimicry of the stilt village where he sat, mocking his poverty with its milled boards and varnish, charging per person per night more than his family’s income for a month. The white man thought this view beautiful? I felt ashamed, and added by way of explanation, ‘We do not have this in my country.’

‘Therefore,’ said Jayari, ‘from what country are you coming?’ I was as much surprised by his tone as by a conjunction straight off the bat. He spoke loudly and was so emphatic in his use of English as to be almost threatening. ‘Therefore’ turned out to be his favourite word and he was pinning me down with questions. He held an interrogative grimace after each, and the slight tremble that moved his old body made him look as though he would explode with rage. His mild ‘Ah, yes,’ once I had given an answer, and the occasional grin that betrayed no hint of a tooth, showed his true character. I told him I wanted to stay with Sarani, and he asked: ‘Therefore, what is your purpose in this roaming around on the sea?’

He assumed I would spend the night at the resort, and even started telling Padili to help me with my bags. He was surprised when I stopped him. ‘But you are rich, and there are many people from your country there.’ I told him I had not come so far to meet people from my own country. ‘Therefore, where will you sleep this night? In which village? Please, do not go to the other side. There are many Suluk people there. Therefore, you will sleep here.’ Padili was sent out for Coca-Cola and an oil lamp was lit. Jayari told me that they, and most of the other people on this side of the island, had left the Philippines three years previously to escape Suluk violence. ‘We want to keep our lives, therefore we came here. They attack us with guns. Please do not trust Suluk people. We cannot do these things. We are good Muslims. If we commit bad things, therefore bad things happen to us. How can they commit such things to human beings? Please do not trust Suluk people.’ His head shook as he stared at me, the corners of his eyes clogged with rheum. The households on his side of the island were mostly Bajau. The village on the other side had been there ten years and was a mixture of Suluk and Bajau, with the balance of power tilted towards the Suluk. Robert Lo’s resort took up the whole of the eastern third. Almost everyone on the island, resort-workers included, was an illegal immigrant.

Food was brought, rice and fried fish, and a jug of well-water. I had been wondering what I would do about drinking water and here was the answer. Jayari said he had learnt English from an American teacher at the Notre Dame school in Bongao during the pre-war days of the Philippine Commonwealth. He remembered Mister Henry with fondness, and his home island that he would not see again. ‘Of course we want to go back, but we want to live, therefore we stay here. Please do not trust Suluk people.’

The sleeping mats were being spread for the night. Beside me, with a mat to itself, was a shallow tray, wooden and filled with what looked like ash. Jayari explained they were the ‘remains’ of his grandfathers, carried with him out of Bongao. Every Bajau house had such a place; the seat of Mbo’. I was intrigued by the duality of their belief, Islam and ancestor worship running side by side, but having declared himself a good Muslim Jayari did not want to talk about it.

He was much more interested in the possibility that I was in possession of cough medicine. His cough kept him awake at night. It made his legs weak and he could not go very far before he became breathless and dizzy. He could only smoke one packet of cigarettes a day, and that was upsetting him. ‘Therefore you will give me medicine.’ He had smoked at least five cigarettes while we were talking, flicking the ash through the gaps between the floorboards. I had tried one. They were menthol, but the mint did little to conceal just how strong and rough the tobacco was. The brand was called ‘Fate’, the packet green with a white rectangle front and back on which was written FATE in black letters below a single black feather. I asked how many he usually smoked. ‘Two packets,’ he said, at which his wife laughed and said, ‘Three.’ She had settled on a pillow by Jayari’s leg, but had given no previous sign of understanding our English conversation. ‘They are very strong,’ I said. ‘Can you smoke another brand?’ The younger men smoked Champion menthols, milder, made in Hong Kong and smuggled from the Philippines. ‘I cannot smoke another one, another one makes me cough. I cannot be happy. Therefore, if you pity me, you will give me medicine.’ I only had the remains of the strip of Disprin I had bought for a hangover in Singapore. He looked at them suspiciously, but squirrelled them away in the wooden box where he kept his smokes.

I had not moved from the spot where I first sat down. I needed to stretch my legs. Jayari sent Padili with me to the shore. Night had fallen. The moon had yet to rise. It was probably not the best moment to negotiate the walkway to the beach for the first time. The crossing involved a nice balancing act on rough planks that merely rested on wonky pilings and bent considerably under my weight. What looked deceptively like handrails in the darkness were in fact wobbly racks for hanging nets and clothes and fish. And now that I was halfway, someone was coming in the other direction. We shimmied past each other somehow. It was with relief that I reached the land, although I scuffed my foot against a lump in the sand, and nearly stumbled.

After a day of being scrutinised and interrogated I wanted to be on my own, and walked off down the beach beyond the last stilt hut. I found a log on which to sit and listen to the palms, stargazing and wondering, therefore, what was my purpose in this roaming around on the sea? Sarani would be here in the morning. He would take me fishing as my father had done when I was a boy, and I had a sudden access to memories of summer holidays in the west of Ireland, a time before the disappointments of growing up, the smells of hay and camomile and burning turf, fishing for mackerel with handlines.

Fishing had been an important part of my father’s Devon childhood, and he had passed his father’s love of it on to me. I caught my first fish aged three. Some of my most worry-free hours have been spent on the river bank. Fishing is a stoic teacher and maybe that was why I had sought out a people who fish as a way of life, to learn what it had taught them.

Two

It was still dark when Sarani called. I came awake instantly. ‘Come,’ he said. I started scrabbling around with my luggage. ‘No, come, look.’

Two boats were moored outside the seaward door, Sarani’s and another, from which a crowd of faces watched me as I climbed down onto its bow. The ceremony began.

A young woman stepped forward, a bright print sarong tied off under her armpits, her shoulders bare. She had the listless air of one who has just woken. She squatted on top of a wooden rice mortar, and an old man wearing a strip of blue cloth around his head and thick spectacles held on with string poured water over her from a coconut shell. He mumbled words that were not meant to be heard. An old woman smoothed down the girl’s long black hair with her hands, the strokes progressing none too gently down to her shoulders, sweeping down each arm, muttering all the while. A young man came forward and was treated to a more perfunctory bath. They each put on dry sarongs and settled down to eat with the others from a large bowl containing a mound of cassava decorated with plantains. Their engine chugged into life, they pushed off from Sarani’s boat, and they were gone, the eastern sky lit as though by orange footlights.

‘They are going to pull up their nets,’ said Sarani in answer to my question, but he was more elusive about what the ceremony meant. For him it did not have a meaning; for him, everything about the ceremony, its form, its purpose, was self-evident. ‘It is Mbo’.’

The sun was already fierce as Sarani poled the boat out to the edge of Mabul’s reef. The tide had started to go out, and we had to get to Kapalai while there was still enough water for us to cross over its fringing reef. It used to be an island, Sarani said, smaller than Mabul and waterless, covered in scrub, but then the house-dwellers of Pulau Tiga cleared it, as they had Mabul some years before that, to plant coconut palms. It washed away quickly, the palm roots unable to hold the sandy soil against the lapping of the sea at high tide, let alone against a storm. All that was left of the island was a sand bar, covered at high tide, but even from Mabul you could see the straight black line of the new jetty that was being built over the reef. As we drew closer it became apparent just how big the structure was, three hundred feet of walkway high off the water, made of top quality milled timber. Obviously it had nothing to do with the Bajau, and Sarani confirmed that one of the resorts was building it, but why they needed such a major platform at Kapalai he did not know.

The sand bar was showing and we steered for the other side from the jetty where a small fleet of boats grew from specks on the horizon. I could count twelve as we skirted the edge of the reef to find a passage through the coral heads. The boats lay in a skein parallel to each other, bows pointing into the wind, and as we came up past them from the stern I caught glimpses of the life of the afterdeck. We throttled back as we passed the lead boat, dropped the anchor, killed the engine and became part of the floating community. It felt unnerving no longer to have a destination. My journeying was at an end and I had arrived in the middle of other people’s lives. I turned away from the lure of the horizon, from the point of the bow that seemed still to forge ahead as it rose and fell on the light waves. I surveyed the flotilla ranged about us like cygnets behind their parent and above the soft noises of the empty sea came the sounds people make when they are at home. We had stopped, we had arrived, but we had not really gone anywhere. We were still on the boat, but the act of stopping, of taking our place in the group, had changed its nature. For the first time, powerfully, I saw Sarani’s boat as more than a vehicle; it was a vessel and I ducked down into the shade of the awning, into the life it contained.

‘This is Arjan,’ said Sarani, and the naked boy, hearing his name, shrank further behind his father’s shoulder. He had a cheap string of shells from the market around his neck and a snotty nose. He must have been two years old. ‘And that is Sumping Lasa.’ The little girl in a dirty patterned green dress, three maybe, with straggling hair, scratching her head. She looked at me suspiciously from a safe distance, her mouth slightly open. Minehanga, Sarani’s young wife, sat nursing their youngest child, a daughter called Mangsi Raya. She had large, strong features and a sharp voice that would carry far across the water. Her jet black hair was twisted into a knot high on her head. She put the kettle on to boil over a kerosene burner, still in its cardboard box, whose lid flaps she used as a windbreak. Mangsi Raya held on to the teat with both hands as her mother bent forward. She had thin light brown curls and a pale skin that had yet to be burned by the sun. She had been born on this boat, on these loose boards, under this tarpaulin.

We were hailed from the boat directly astern and Sarani slackened off the bow rope until our stern was alongside its prow. It belonged to Pilar, Sarani’s youngest son by his first wife. Pilar had a dug-out to return, and his wife, Bartadia, had our breakfast in a basin, strips of plantain, battered and fried. She wore a sarong piled on her head and a face mask of green paste to protect her skin from the sun. She was pretty nonetheless, and her eye-teeth, like Pilar’s, were capped with gold. Their eighteen-month-old son, Bingin, burst into tears the moment he saw me and hid his face in the folds of his mother’s track-suit top. Mother and son stayed up on the bow while Pilar climbed down nimbly, tied off the dug-out’s painter and threw Arjan, his half-brother, who was already clamouring for the food, high into the air. He went up screaming and came down laughing, reaching for the basin as it passed over his head. He plonked himself down on the deck hard by the rim and tucked in with both hands. He burnt his fingers.

Sarani answered their questions about me as we sat on the stern eating – of the other adults only Pilar spoke any Malay – referring to me occasionally for confirmation. ‘You do come from Italy, don’t you?’ Arjan spoke a language all his own as he waved his food around, and threw some over the side, but he understood when Sarani sent him off for his Tupperware betel box, running up to the bow and rattling the loose planking. Sarani prepared a plug and climbed down into the dug-out to sort out the net that lay in its bottom. Minehanga put the rest of the plantain into another bowl and passed it down to him. He wedged it into the bow with his betel box, spat red juice and said, ‘You want to come fishing?’

I had been in dug-outs before, though not on the sea. They are tricky craft at the best of times, and the best of times are when you are safely in and sitting down, with your weight low and a paddle in your hands. The getting in and the getting out are the interesting bits, and getting into this dug-out had the potential to be very interesting indeed. I had not fallen out of one before, but there is always a first time. My audience, which had grown from the occupants of our two boats to include everyone on the sterns of the other boats nearby, waited expectantly. This dug-out was old and leaky, but it looked big enough and broad enough in the beam to take us both. Its sides had weathered to the point where the soft wood in the grain was rotting away, leaving the surface corrugated. Cracks were caulked with coconut fibre, strips of flip-flop rubber and plastic bags. There was seaweed growing on the inside, a fine green algae, watered by a tidal pool that never drained completely. A baby crab the colour of coral sand tried to hide under the net. Sarani was perched nonchalantly above the bow, squatting on his heels, one foot up on either side of the dug-out. I doubted my embarkation would show as much poise. Sarani turned the canoe so that I could step down into the middle from where I sat on the stern of the boat. I kept my balance long enough to sit down in the puddle, which brought a laugh. Sarani told me to move down over the net, to the plank seat in the stern. I was not too proud to crawl.

He had some social calls to make. We toured the busy afterdecks of our neighbours’ boats. At one we handed over the plantains and received a baler in return, a cut-off plastic motor-oil bottle that I was given to use. At another we filled our bowl with cassava damper. At all the curious were told I was from Italy. We turned away from the fleet and poled our way slowly over the sandy shallows, still under a fathom of water, towards the reef. The wind dropped away as though before a storm and ahead lay calm water and the three hottest hours of the day.

A silence enveloped us, complete apart from the pole dipping into water, trailing a bright arc over the surface, dipping again. As I looked over the side of the dug-out, through the green-tinted, vitreous translucence, a shoal of anchovies turned in unison away from Sarani’s pole, invisible until the moment the sun caught their silver sides and they broke from the water in a sudden effervescence. ‘Ikan bilis,’ said Sarani, ‘delicious, dried then fried.’ A small ray flew away over the sand between the coral heads, and he started up with a hunter’s reactions, though he had no spear. He stood on the bow and watched for where it would settle, but it did not stop within sight. He scanned the shallows for a long time. I had noticed how his bearing changed the moment he stepped off the land, where he seemed at a loss, walking with bent legs and wearing a half-puzzled, half-fearful expression. Now we were in his element, on the sea, where his actions had the grace of instinct. Standing in the bow, his feet seemed to rest on the horizon itself.