Полная версия

In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in the Congo

Prime Minister Lumumba appointed Mobutu army chief of staff. Touring the country’s military bases, playing up his own army experience, Mobutu persuaded the soldiers to return to barracks. But the mutiny was not Lumumba’s only problem. Belgian paratroopers had landed in what the Congolese assumed to be a second colonial takeover. The new state seemed doomed to break up as, encouraged by a former colonial master bent on ensuring continued access to Congo’s mineral wealth, first copper-producing Katanga and then diamond-rich Kasai seceded.

The UN responded to the crisis with extraordinary speed. Its reaction time, like the hordes of journalists who flooded into Congo to cover those years, was a measure of the enormous hopes the West was pinning on Africa during those years. Impossible as it is to imagine in the year 2000, when the renewed threat of national fragmentation raises barely a flicker of international interest, the Congo of the 1960s was one of the world’s biggest news stories.

The first UN troops landed in Leopoldville the day after Lumumba and President Joseph Kasavubu called on the UN Security Council for protection from foreign aggression. But Lumumba, who had hoped they would help snuff out the secession movements in the south, was bitterly disappointed by their limited mandate, which barred them from interfering in Congo’s internal conflicts.

Feeling betrayed by the West, -Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for help, requesting transport planes, trucks and weapons to wipe out the breakaway movements in Kasai and Katanga. Nikita Khrushchev obliged. The military aid arrived too late to prevent a bloody debacle in Kasai, where the Congolese army lost control, slaughtering hundreds of Luba tribespeople. But for Washington what mattered was that this was the first time Moscow had intervened militarily in a conflict so far from its own borders. It represented a dangerous ratcheting up of the Cold War game.

‘I had a little Congolese sitting at the airport counting any white man who came off a Soviet aircraft in batches of five. Roughly 1,000 came in during a period of six weeks. They were there as “conseillers techniques” and they were posted to all the ministries,’ recalled Devlin. ‘To my mind it was clearly an effort to take over. It made good sense when you stopped to think about it. All nine countries surrounding the Congo had their problems. If the Soviets could have gotten control of the Congo they could have used it as a base, bringing in Africans, training them in sabotage and military skills and sending them home to do their duty. I determined to try and block that.’

It was a line of argument that was to justify more than three decades of American support. But if for Washington Lumumba was showing a worrying resemblance to Fidel Castro, Devlin himself, ironically enough, never believed in the sincerity of Lumumba’s conversion to the Soviet cause. ‘Poor Lumumba. He was no communist. He was just a poor jerk who thought “I can use these people”. I’d seen that happen in Eastern Europe. It didn’t work very well for them, and it didn’t work for him.’

The wave of Soviet arrivals triggered the collapse of Lumumba’s strained relations with Kasavubu, Congo’s lethargic president. At times, too many times, politics in Congo resembled one of those hysterical farces in which policemen with floppy truncheons and red noses bounce from one outraged prima donna to another. ‘I’m the head of state. Arrest that man!’ ‘No, I’M the head of state. That man is an impostor. Arrest him!’ Only the reality was more dangerous than amusing. In a surreal sequence the prime minister and president announced over the radio that they had sacked each other. Mobutu was put in an impossible position, with both men ordering him to take their rival into custody.

The army chief of staff was already unhappy with the turn events were taking. ‘The Russians were brutally stupid. It was so obvious what they were doing,’ marvelled Devlin. ‘They sent these people to lecture the army. It was the crudest of propaganda, 1920s Marxism, printed in Ghana in English, which the Congolese didn’t understand. Mobutu went to Lumumba and said “let’s keep these people out of the army”. Lumumba said “sure, sure I’ll take care of that”, but he didn’t. It kept happening and finally Mobutu said: “I didn’t fight the Belgians to then have my country colonised a second time.”’

Exactly what role Devlin played in determining subsequent events was not clear. Cable traffic between Leopoldville and Washington shows he received authorisation for an operation aimed at ‘replacing Lumumba with a pro-Western group’ in mid-August 1960. Despite his friendliness, Devlin remained bound by the promises of confidentiality made to the CIA, contemptuous of those in the intelligence services who leaked government secrets. All he would say was that it was during those dramatic days that he really got to know Mobutu. The army chief was already being leaned on by the Western embassies – whose advice was given added weight by the fact that they were helping him pay his fractious troops – President Kasavubu, the student body and his own men. No doubt the CIA station chief brought his own persuasive skills, that talent acquired during years of ‘turning’ Soviet personnel, into play as Mobutu edged towards one of the hardest decisions of his life.

The eventual outcome, Devlin acknowledged, came as no surprise. On 14 September 1960, Mobutu neutralised both Kasavubu and Lumumba in what he described as a ‘peaceful revolution’ aimed at giving the civilian politicians a chance to calm down and settle their differences. Soviet bloc diplomatic personnel were given forty-eight hours to leave. The huge African domino had not fallen: Congo had been kept safely out of Soviet hands.

It was exactly what Washington wanted. But Devlin nonetheless rejected any notion of Mobutu being an American tool. ‘He was never a puppet. When he felt it was against the interests of the Congo, he wouldn’t do it, when it didn’t go against his country’s interests, he would go along with our views. He was always independent, it just happened that at a certain point we were going in the same direction.’ And like many commentators of the day, he still believed that Mobutu, an earnest twenty-nine-year-old pushed to prominence by a failure of leadership and a jumble of cascading events rather than personal ambition, was genuinely reluctant to take over in 1960. Such modesty would not last very long.

Who was the man who so impressed Devlin and the diplomats as they circulated, glasses in hand and mental notebooks at the ready, at the reception in Brussels?

Joseph Désiré Mobutu was born on 14 October 1930 in the central town of Lisala, where the Congo river runs deep and wide after its grandiose circular sweep across half a continent. That early proximity to the river, he always claimed, left him with a visceral love of the water. ‘I can say that I was born on the river … Whenever I can, I live on the river, which for me represents the majesty of my country.’

He was a member of the Ngbandi tribe, one of the smaller of the country’s 200-plus ethnic groupings. Anthropologists believe the Ngbandi trace their lineage back to the central Sudanese regions of Darfur and Kordofan, an area that was repeatedly targeted by Moslem Arab conquerors from the sixteenth century onwards. Fleeing the slave raids and Islamicisation, his animist ancestors fled south, heading for the very equatorial heart of the continent, where they in turn subjugated the local Bantus. Safe in the glowering forests that later so terrified Western explorers, they intermarried and the Ngbandi – who took their name from a legendary fighter – gradually acquired an identity. They emerged as a loose affiliation of war-like tribes speaking the same language and straddling the Ubangi, a subsidiary of the great Congo river, with one foot in what is today Central African Republic and another in Congo.

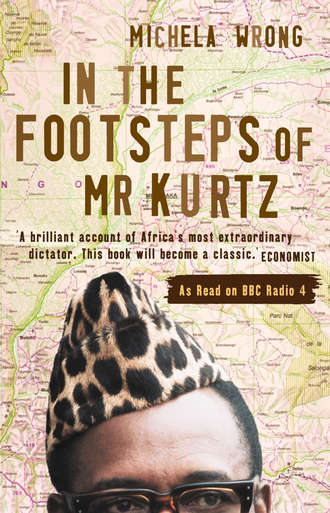

Like all autocrats, Mobutu was later to mythologise his own upbringing. In one story, almost certainly apocryphal, he described walking in the woods with his grandfather. When a leopard leaped from the undergrowth, the boy shrank away. The grandfather remonstrated with him and, ashamed and piqued, the young Mobutu seized a spear and slew the leopard. ‘From that day on,’ said Mobutu, ‘I am afraid of nothing.’ He was to use the animal at the centre of this coming-of-age fable as his personal insignia, a symbol of pride, strength and courage. It was also the origin of his trademark leopard-skin hats which, in a curious juxtaposition of machismo and decadence, he had made by a Paris couturier, keeping a collection of at least seven on hand.

The truth of those early years is somewhat less romantic. Some of Mobutu’s contemporaries recall that in the pre-independence era, there was a tendency amongst city dwellers to sneer at the Ngbandi, marooned in one of the least accessible zones of Africa, as coarse rustics who had barely shed their loin-cloths in favour of Western-style clothing; good hunters, yes, but in need of some urban refinement.

Mobutu would later ensure that changed. But when he was growing up, he belonged to a tribe regarded as ‘sous-evolué’ – under-evolved. He shared with many prominent men a keen awareness of his humble origins, a source of resentment pushing him ceaselessly, fruitlessly, to try and prove his superiority. And if Mobutu’s ethnic origins were not enough of a burden, there was another issue calculated to niggle at the confidence of an impressionable youngster – his parentage.

His mother Marie Madeleine Yemo, whom he adored, was a woman who had notched up her fair share of experiences. She had already had two children by one relationship when her aunt, whose marriage to a village chief was childless, arranged for her niece to join her husband’s harem. It was a kind of brood-mare, stand-in arrangement that, while strictly in accordance with local custom, must have contained its share of bitterness and humiliation for both of the women concerned.

Mama Yemo, as she was eventually to be known to the nation, bore the chief two children, then twins who died. Suspecting her aunt of witchcraft, she fled on foot to Lisala. It was there that she met Albéric Gbemani, a cook working for a Belgian judge. The two staged a church wedding just in time, two months before Joseph Désiré Mobutu’s birth. The boy’s name, with its warrior connotations, came from an uncle.

Recalling his youth, Mobutu later had more to say about the kindness shown by the judge’s wife, who took a shine to him and taught him to read, write and speak fluent French, than his own father, who barely features. ‘She adopted me, in a way. You should see it in its historical context: a white woman, a Belgian woman, holding the hand of a little black boy, the son of her cook, in the road, in the shops, in company. It was exceptional.’

Given that Albéric died when Mobutu was barely eight years old, the dearth of detail about his father is perhaps not surprising. But that lacuna was later seized upon by Mobutu’s critics, who would caricature their leader as the bastard offspring of a woman only a few steps up from a professional prostitute.

With his mother relying on the generosity of relatives to support her four children, Mobutu’s existence became peripatetic as she moved around the country. Periods in which he ran wild, helping out in the fields, alternated with stints at mission schools. He later claimed that religious exposure left him a devout Catholic, but as with many Congolese, his Christianity never ruled out a belief in the African spirit world which left him profoundly dependent on the advice of marabouts (witch-doctors).

Mobutu finally settled with an uncle in the town of Coquilhatville (modern-day Mbandaka), an expanding colonial administrative centre. The placing by rural families of their excess offspring with urban relatives who are then expected to shoulder their upkeep and education for years, often decades, is extraordinarily prevalent in Africa. Puzzling to Westerners, such generosity is a manifestation of the extended family which ensures that one individual’s success is shared as widely as possible. But the burden is often almost too heavy to bear, and such children never have it easy. For Mobutu, life was tough. Perhaps the austerity of those days, when he depended on a relative for food and clothing, explains his love of excess, the unrestrained appetites he showed in later life.

In Coquilhatville he attended a school run by white priests, and the child whose precocity had already been encouraged by a white woman began to acquire a high profile. Physically, he was always big for his age, a natural athlete who excelled at sports. But he wanted to dominate in other ways as well. ‘He was very good at school, he was always in the top three,’ remembers a fellow pupil who used to play football with Mobutu in the school yard. ‘But he was also one of the troublemakers. He was the noisiest of all the pupils. The walls between classrooms were of glass, so we could see what was going on next door. He was always stirring things up. It wasn’t done out of malice, it was done to make people laugh.’

One favourite trick was making fun of the clumsy French spoken by the Belgian priests, most of whom were Flemish. ‘When they made a mistake he would leap up and point it out and the whole room would explode into uproar,’ said a contemporary. Another jape involved flicking ink darts at the priest’s back while he worked at the blackboard, a trick calculated to get the class giggling.

In later life, like any anxious middle-class parent, Mobutu would drum into his children the importance of a formal education. One such lecture occurred when the presidential family was aboard the presidential yacht, moored not far from Mbandaka. On a whim, Mobutu sent for the priests from his old school and ordered them to bring his school reports. Miraculously, they still had them and Nzanga, one of Mobutu’s sons, remembered his father proudly showing his sceptical offspring that, academically at least, he had been no slouch.

Given that he did well academically, Mobutu, known as ‘Jeff’ to his friends, was forgiven a certain amount of unruliness. But the last straw came in 1949 when the school rebel stowed aboard a boat heading for Leopoldville, the capital of music, bars and women regarded by the priests as ‘sin city’. Mobutu met a girl and, swept away by his first significant sexual experience, extended his stay. After several weeks had passed, the priests asked a fellow pupil, Eketebi Mondjolomba, where Mobutu had gone.

‘Since we lived on the same street, I was supposed to know where he was and I said, in all innocence, he’d gone to Kinshasa,’ remembered Eketebi, who was still grateful that Mobutu later laughingly forgave – while definitely not forgetting – this youthful indiscretion. ‘At the end of the year, that was one of the reasons why he was sent to the Force Publique. It was the punishment the priests and local chiefs always reserved for the troublesome, stubborn boys.’

The sudden expulsion was a shock. It meant a seven-year obligatory apprenticeship in an armed force still tainted by a reputation for brutality acquired during the worst excesses of the Leopold era. But for Mobutu the Force Publique was to prove a godsend. Here the natural rebel found discipline and a surrogate father figure in the shape of Sergeant Joseph Bobozo, a stern but affectionate mentor. In later life, bloated by good living and corroded by distrust for those around him, he would wax nostalgic about the austere routines of army life and the simple camaraderie of the barracks. Looking back, he recognised this as the happiest period of his life.

In truth, Mobutu was never quite as much of a military man as he liked to make out. Of more importance in furnishing his mental landscape was the fact that he managed to keep his education going in the Force Publique, corresponding regularly with the mission pupils he had left behind, who kept him closely informed of how their studies were progressing. On sentinel duty, carrying out his chores, he read voraciously, working through the European newspapers received by the Belgian officers, university publications from Brussels and whatever books he could lay hands on. It was a habit he retained all his life. He knew tracts of the Bible off by heart. Later, his regular favourites were to give a clear indication of the sense of personal destiny that had developed: President Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill and Niccolò Machiavelli, author of The Prince, that autocrat’s handbook.

He took and passed an accountancy course and began to dabble in journalism, something he had already practised at school, where he ran the class journal. And he got married. Marie Antoinette, an appropriate name for the wife of a future African monarch, was only fourteen at the time, but in traditional Congolese society this was not considered precocious. Still smarting from his schoolroom clashes with the priests, Mobutu chose not to wed in church. His contribution to the festivities – a crate of beer – betrayed the modesty of his income at the time.

Photos taken during those years show a gawky Mobutu, all legs, ears and glasses, wearing the colonial shorts more reminiscent of a scout outfit than a serious army uniform. Marie Antoinette, looking the teenager she still was, smiles shyly by his side. Utterly loyal, she was nonetheless a feisty woman, who never let her husband’s growing importance cow her into silence. ‘You’d be talking to him and she would come in and chew him up one side and down the other,’ said Devlin. ‘She was not impressed by His Eminence, and he would immediately switch into Ngbandi with her because he knew I could understand Lingala or French.’

A Belgian colonial had started up a new Congolese magazine, Actualités Africaines, and was looking for contributors. Because Mobutu, as a member of the armed forces, was not allowed to express political opinions, he wrote his pieces on contemporary politics under a pseudonym. Given the choice between extending his army contract and getting more seriously involved in journalism, he chose the latter. Although initial duties involved talent-spotting Congolese beauties to fill space for an editor nervous of polemics, Mobutu was soon writing about more topical events, scouring town on his motor scooter to collect information. The world was opening up. A 1958 visit to Brussels to cover the Universal Exhibition was a revelation and he arranged a longer stay for journalistic training. By that time he had got to know the young Congolese intellectuals who were challenging Belgium’s complacent vision of the future, staging demonstrations, making speeches and being thrown into jail.

One man in particular, Lumumba, became a personal friend. The two men shared many of the same instincts: a belief in a united, strong Congo and resentment of foreign interference. Thanks to his influence Mobutu, who had always protested his political neutrality, was to become a card-carrying member of the National Congolese Movement, the party Lumumba hoped would rise above ethnic loyalties to become a truly national movement.

But even in those early days there are question marks over Mobutu’s motives. Congolese youths studying in Brussels were systematically approached by the Belgian secret services with an eye to future cooperation. Several contemporaries say that by the time Mobutu had made his next career step – moving from journalism to act as Lumumba’s trusted personal aide, deciding who he saw, scheduling his activities, sitting in for him at economic negotiations in Brussels – he was an informer for Belgian intelligence.

What were the qualities that made so many players in the Congolese game single him out? Some remarked on his quiet good sense, the pragmatism that helped him rein in the excitable Lumumba when he was carried away by his own rhetoric. It accompanied an appetite for hard work: Mobutu was regularly getting up at 5 in the morning and working till 10 p.m. during the crisis years. But the characteristic that, more than any other, eventually decreed that he won control of the country’s army was probably the brute courage he attributed to that childhood brush with the leopard.

Bringing the 1960 mutiny to heel involved standing up in front of hundreds of furious, drunk soldiers who had plundered the barracks’ weapons stores and quelling them through sheer force of personality. And Mobutu carried out that task, one that civilian politicians understandably balked at, not once but many times. ‘I’ve been in enough wars to know when men are putting it on and when they really are courageous,’ said Devlin. ‘And Mobutu really was courageous.’ Once, he watched Mobutu curb a mutiny by the police force. ‘They were hollering and screaming and pointing guns at him and telling him not to come any closer or they’d shoot. He just started talking quietly and calmly until they quietened down, then he walked along taking their guns from them, one by one. Believe me, it was hellish impressive.’

The quality was to be tested repeatedly. The assassination attempt foiled by Devlin’s intervention was one of five such bids in the week that followed Mobutu’s ‘peaceful revolution’. Such was the danger that Mobutu sent his family to Belgium. Marie-Antoinette deposited her offspring and returned in twenty-four hours, refusing to leave her husband’s side. ‘If they kill him they have to kill me,’ she told friends.

What constitutes charm? A presence, a capacity to command attention, an innate conviction of one’s own uniqueness, combined, as often as not, with the more manipulative ability of making the interlocutor believe he has one’s undivided attention and has gained a certain indefinable something from the encounter. Whatever its components, the quality was innate with Mobutu, but definitely blossomed as growing power swelled his sense of self-worth. In the early 1960s European observers referred to him as the ‘doux colonel’ (mild-mannered colonel), suggesting a certain diffidence. Nonetheless he was a remarkable enough figure to prompt Francis Monheim, a Belgian journalist covering events, to feel he merited an early hagiography. By the end of his life, whether they loathed or loved him, those who had brushed against Mobutu rarely forgot the experience. All remarked on an extraordinary personal charisma.

‘I’ve never seen a photograph of Mobutu that did him justice, that makes him look at all impressive,’ claimed Kim Jaycox, the World Bank’s former vice-president for Africa, who met Mobutu many times. ‘It’s like taking a photograph of a jacaranda tree, you can’t capture the actual impact of that colour, of that tree. In photos he looked kind of unintelligent and without lustre. But when you were in his presence discussing anything that was important to him, you suddenly saw this quite extraordinary personality, a kind of glowing personality. No matter what you thought of his behaviour or what he was doing to the country, you could see why he was in charge.’

He had a gift for the grand gesture, a stylish bravado that captured the imagination. Setting off for Shaba to cover the invasions of the 1970s, foreign journalists would occasionally disembark to discover, to their astonishment, that their military plane had been flown by a camouflage-clad president, showing off his pilot’s licence.

There were some of the personal quirks that can count for much when it comes to political networking and pressing the flesh, whether in a democracy or a one-party state. He had a superb memory and on the basis of the briefest of meetings would be able, re-encountering his interlocutor many years later, to recall name, profession and tribal affiliation. ‘It was phenomenal,’ remembers Honoré Ngbanda, who as presidential aide for many years was responsible for briefing Mobutu for his meetings. ‘Whether it was a visual memory or a memory for dates, he could remember things that had happened 10 years ago: the date, the day and time. His memory was elephantine.’

Mobutu had another of the characteristics of the manipulative charmer: he could be all things to all men, holding up a mirror to his interlocutors that reflected back their wishes, convincing each that he perfectly understood their predicament and was on their side. ‘He could treat people with kid gloves or he could treat them with a steel fist,’ remembered a former prime minister who saw more of the fist than the glove. ‘It was different for everyone. He was very clever at tailoring the response to the individual.’