Полная версия

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Elizabeth, by contrast, was ever more visible in the popular magazines – with interest enhanced by speculation about the developing but unannounced romance. The American press, always ahead of the British, anticipated an engagement early in 1947 by turning her into a cover girl, a newsreel star, and – highest compliment – the ultimately desirable girl-next-door. In January 1947, the International Artists’ Committee in New York voted her one of the most glamorous women in the world. In March, Time declared her ‘the Woman of the Week’, and praised her for her ‘Pin-Up Charm’. Devoting four pages to her life story, it revealed her as a princess the magazine’s readers could take to their hearts. She was practical, down-to-earth, human – the essence of suburban middle America. As well as being an excellent horsewoman she was, the article declared, a tireless dancer and an enthusiastic lover of swing music, night clubs, and ‘having her own way’. She enjoyed reading best-sellers, knitting and gossipy teas with her sister and a few girlfriends in front of the fire at Buckingham Palace.17

According to Crawfie, she was an indifferent knitter.18 However, the picture was not entirely false. Whatever she may have read in her teens, her adult tastes in literature and drama were, as a British observer put it delicately in the 1950s, ‘those of the many rather than the few’.19 In this respect, as in others, efforts to nip any blue-stocking tendency in the bud had succeeded.

It was also true that she enjoyed music, especially if it was not too demanding. She took a keen interest in the ‘musicals’ currently in vogue on the London stage. She liked the satirical entertainment 1066 and All That so much that she obtained a copy of the song ‘Going Home to Rome’ from the management.20 Jean Woodroffe (then Gibbs), who became her lady-in-waiting early in 1945, remembers that the two of them would while away the time on long car journeys to and from official engagements by singing popular songs.21 After the war ended, weekly madrigal sessions were held at the Palace – either Margaret or a professional musician played the piano and both girls sang, together with some officers in the Palace guard.22

One madrigal singer was Lord Porchester (now the seventh Earl of Carnarvon) who had known Princess Elizabeth when he was in the Royal Horse Guards at the end of the war, and had taken part in the Buckingham Palace VE-Night escapade. Porchester (‘Porchey’)* also shared the Princess’s interest in riding, breeding and racing horses. During the war, they had seen each other at the Beckhampton stables on the Wiltshire Downs, where horses bred at the royal studs were trained. Porchester was the grandson of the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, who, as well as being the joint discoverer of the tomb of Tutenkhamun, had been the leading racehorse owner-breeder at the beginning of the century, and had set up the Highclere Stud at his Hampshire home. His father, the sixth Earl, had bred the 1930 Derby winner Blenheim. ‘The King thought I was a suitable racing companion of her age group,’ says Lord Carnarvon. ‘There were not many people then who could accompany her to the races.’ Since the 1940s, he says, ‘We have developed our interest together, and it has got sharper.’23 He was beside her at Newmarket in October 1945, and at almost every Derby since.

Before the war, horses had been Elizabeth’s childhood fantasy. During it, her confidence as a rider had been built up with the help of Horace Smith. After 1945, the horse world became her chief relaxation and escape. She read widely on the subject, extending her knowledge of horse management, welfare and veterinary needs, and she developed a sixth sense as a trainer. ‘She has an ability to get horses psychologically attuned to what she wants,’ says Sir John Miller, for many years Crown Equerry and responsible for all the Queen’s non-race horses, ‘and then to persuade them to enjoy it.’24 What started as a hobby later became a serious enterprise, and an area for her own independent professionalism. ‘Prince Philip shrewdly kept out of it all,’ says a former royal employee. ‘Otherwise he would have dominated the discussion.’25

For Elizabeth, horse breeding was a family interest. The royal studs had been founded at Hampton Court in the sixteenth century, later moving to Windsor. In the late nineteenth century, the then Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, had re-confirmed the royal hobby by establishing the Sandringham stud. Royal interest seemed curiously, though perhaps not surprisingly, to mirror the royal fascination with dynastic genealogy. The result had been an exclusive attitude to bloodlines. ‘Royal managers had avoided sending to some of the best stallions, often because they did not like the owner,’ Carnarvon recalls. On one occasion, an otherwise ideal candidate for covering a royal mare was rejected by Captain Charles Moore, George VI’s (and later his daughter’s) Manager of the Royal Studs, on the grounds that it belonged to a bookmaker. In much the same way, the King – who took a mild interest in racing – had a patriotic approach to the sport. Not only did he prefer to send to British-based stallions, it upset him if French horses too often won British races.26

Lord Porchester, who had studied at Cirencester Agricultural College and had acquired a knowledge of the principles of ‘hybrid vigour,’ tried to advance royal practice by encouraging the family to be less fussy about equestrian social backgrounds. As Porchey and Elizabeth became more expert together, a quiet revolution came eventually to overtake royal breeding methods. After Elizabeth became Queen, her interest increased, and in 1962 she leased Polhampton Lodge Stud, near Overton in Hampshire, for breeding race horses – adding to the studs (Sandringham and Wolverton) at Sandringham. In 1970, Lord Porchester took over as the Queen’s racing manager. Over the years their shared passion for horses became the basis for a close friendship. ‘With Henry Porchester, racing and horses bring them continually together,’ says a former royal adviser. ‘Henry tells her a lot of gossip. She’s very fond of him and he’s devoted to her.’27

Princess Elizabeth’s other recreations were also uncompromisingly those of royalty and the landed aristocracy. Like her grandfather, father and mother, she was relentless in her pursuit of the fauna on the Sandringham and Balmoral estates. She did not use a shotgun, but she became skilled with a rifle, and in stalking deer during Scottish holidays. One report described how, while staying on the Invernesshire estate of Lord Elphinstone, the Queen’s brother-in-law, in October 1946, the twenty-year-old Princess followed a stag through the forest, ‘aimed with steadiness and brought down the animal,’ which turned out to be a twelve-pointer.28 It was a sport for which she was well-equipped. After visiting Balmoral during the war, King Peter of Yugoslavia, Alexandra’s husband, expressed admiration at the quality of the rifle she lent him.29 Later, Porchey gave her a .22 rifle as a present.

The pace quickened at the end of the war, in shooting as in everything else. Aubrey (now Lord) Buxton, a Norfolk neighbour who became a close friend of the royal couple – and who later helped to inspire Philip’s interest in wildlife and conservation – described one extraordinary day’s shooting at Balmoral, a fortnight after the Japanese surrender. A royal house party, headed by the Monarch, set itself the task of killing as wide a range of different birds and animals as possible. The King set out in search of ptarmigan, somebody else had to catch a salmon and a trout, and so on. After a hard day, the final bag in the game book was 1 pheasant, 12 partridges, 1 mountain hare, 1 brown hare, 3 rabbits, 1 woodcock, 1 snipe, 1 wild duck, 1 stag, 1 roe deer, 2 pigeons, 2 black game, 17 grouse, 2 capercailzie, 6 ptarmigan, 2 salmon, 1 trout, 1 heron and a sparrow hawk. Princess Elizabeth was the proud dispatcher of the stag.30

Margaret did not share Elizabeth’s sporting enthusiasms – one of the factors which led to the growth of different and contrasting circles of friends. To some extent, despite the age gap, their circles overlapped. Weekend parties in the mid-1940s included the heirs to great titles, who were regarded as potential husbands for either of them. Names like Blandford, Dalkeith, Rutland, Euston, Westmorland tended to crop up. ‘There was a good deal of speculation,’ an ex-courtier remembers, ‘about whether any of them would do.’ When Philip became a fixture, the circles diverged. Margaret began to attract a smarter set: her friends thought of themselves as gaier, wilder, wittier, and regarded Elizabeth’s as grand, conventional and dull.

As well as the gap in interests, the distinction reflected a difference in temperament. ‘Princess Margaret loved being amused,’ suggests one of her friends, ‘in a way that her sister didn’t.’ It was also a product of the princesses’ contrasting relationship with the King. Elizabeth, the introvert, had been brought up to be responsible; Margaret, the extrovert, to be pretty, entertaining and fun. ‘George VI had a strong concern for Princess Elizabeth,’ says the same source, ‘but he had a more fatherly attitude towards her sister. I remember him leaning on a piano when she was singing light-hearted songs, with an adoring look, thinking it was frightfully funny.’ While Margaret reached out to people, Elizabeth seemed never to give much away. A lady-in-waiting recalls her, in the mid–1940s, as ‘very charming, but very quiet and shy – much more shy than later.’31 Colville formed a similar impression. ‘Princess Elizabeth has the sweetest of characters,’ he recorded, shortly after joining her, ‘but she is not easy to talk to, except when one sits next to her at dinner, and her worth, which I take to be very real, is not on the surface.’32

The impression of Princess Elizabeth is of a strangely poised young person used to going her own way, which tended to be the way of her class rather than of her age group, and making few concessions to fashion. Yet the sense of her as highly conventional – in contrast to her sister – depends partly on the vantage-point and the generation of the observer. Simon Phipps, friendly with Margaret when he was a theological student and young clergyman, and who later became Bishop of Lincoln, remembers the stiffness of royal protocol, including having to change twice in the evening (once for tea, and again for dinner), and turning at table when the Monarch turned. But he also recalls happy games of charades, including an anarchic one in which he was cast as a bishop, and the King as his chaplain.33 When Lady Airlie, Queen Mary’s friend and lady-in-waiting, visited Sandringham in January 1946, what shocked her was the extent of change since before the war. She found youth in control, with jig-saw puzzles set out on a baize-covered table in the entrance hall. ‘The younger members of the party – the princesses, Lady Mary Cambridge, Mrs Gibbs and several young guardsmen congregated round them from morning to night,’ she noted. ‘The radio, worked by Princess Elizabeth, blared incessantly.’ No orders or medals were worn at dinner, as they had been in the old days, and the girls related to their parents with – to Lady Airlie – startling informality. Modernity was also visible ‘in the way both sisters teased, and were teased by, the young Guardsmen.’34

Teasing and teased Guards Officers were, however, only one aspect of their lives. The chasm that divided the King’s daughters from the young men and women they were able to meet socially, widened early in 1947 when they accompanied their parents on a major tour of southern Africa which attracted world attention, and set the stage for Princess Elizabeth’s début as a fully-fledged royal performer.

The end of the war had given a brief, almost paradoxical, boost to the imperial ideal. Partly, it was an effect of sheer survival – defending the Empire had been one of the causes for which the war had been fought. Britain’s near-bankruptcy had made the vision of a shared, transoceanic loyalty all the more necessary to national self-esteem: a necessity which the granting of self-government to India seemed, if anything, to increase. At the same time, the British Government was aware that the bonds that tied together the Commonwealth were in need of repair. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the case of Pretoria, capital of a Union still bitterly divided between English-speakers and Afrikaners.

Officially, the tour – which involved a total of four months’ travel – was supposed to be a chance for the King and Queen to rest after the ordeal of war. In practice, the schedule prepared for the Royal Family was strenuous, and the objectives highly political. Wheeler-Bennett later called it a ‘great imperial mission’35. That was one way of describing it. From the South African point of view, the visit was (in the words of another historian) ‘essentially a mission to save Smuts and the Crown of South Africa’.36 English-speakers were enthusiastic about it, Afrikaners on the other hand, were cynical – seeing George VI (according to the High Commissioner, in a telegram to the Palace) ‘as the symbol of the “Empire-bond” which they had pledged themselves to break.’ General Smuts was accused of having arranged the trip in order to rally the English section round him for the coming general election.37 But there was also something else, which in one sense made nationalist Boers right to be suspicious: the royal trip had an ‘imperial’ aspect that went beyond the attempt to improve relations with the Union. South Africa was important in a new ‘multi-cultural’ definition of the Commonwealth – in the light of Indian independence – because it was the only ‘white’ dominion that was in reality predominantly black. The royal visit was to be a way of showing Windsor and Westminster interest in what one (pro-British) Natal paper described as ‘the complex problems of race relationships – problems which are certain to assume an increasing importance in the years ahead,’ in the many countries which owed allegiance to the Crown.38

These factors, however, were not the ones that got the most publicity. In the eyes of the world, the tour also had a personal and dynastic interest: Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip would be apart for four months. Since the invitation was accepted by the King on behalf of the whole Royal Family in the first half of 1946, the trip could hardly be seen as an attempt to break up the friendship. Yet the visit took place as speculation was at its height; and the irony did not escape the gossip-writers that the first major tour on which the King and Queen proposed to take their elder daughter was also one on which she had reason to be reluctant to accompany them.

Why was there no engagement announcement before they set out? A belief that all was not going smoothly added to the press excitement. One former courtier suggests that – whatever the original intention – the King and Queen saw the visit as an opportunity for reflection. ‘Undoubtedly there was hesitation on the part of her parents,’ he says. ‘They weren’t saying “You must or mustn’t marry Prince Philip,” but rather, “Do you think you should marry him?” It wasn’t forced. The King and Queen basically said: “Come with us to South Africa and then decide”.’39

With Philip’s naturalization due to be gazetted in a few weeks, however, any pretence that the relationship did not exist was abandoned. A couple of nights before the departure of the Royal Family, Elizabeth accompanied both her parents to dinner with the Mountbattens, including the about-to-be Philip Mountbatten, at 16 Chester Street – serenaded by Noël Coward. ‘The royal engagement was clearly in the air that night,’ recalled John Dean, Mountbatten’s butler and later valet to Philip.40 It was a farewell meal in two senses. While the King prepared to inspect one of his domains, Uncle Dickie was about to negotiate the transfer of power, as George VI’s Viceroy of India, in another.

MUCH OF THE journey to Cape Town, aboard the battleship HMS Vanguard, was uncomfortably rough, confining the Royal Family to their cabins. When she returned to South Africa as Queen several decades later, Elizabeth recounted how sea-sick they had been. However, as they travelled south they left Europe’s worst winter weather of the century behind them. ‘Our party seems to be enjoying themselves, especially the princesses,’ Lascelles wrote to his wife, describing ‘crossing the line’ festivities, and a treasure hunt involving the King’s daughters and the midshipmen. ‘Peter T[ownsend],’ he added, referring to an equerry who was a member of the party, ‘tries hard and is doing well.’41

For the two young women, the experience was breathtaking – not least because it was the first time either of them had been abroad. In the 1930s, they had been considered too young to accompany their parents on foreign visits, and during the war it had been too dangerous, or impracticable, to do so. Thus, Princess Elizabeth had reached the age of twenty before setting foot outside the United Kingdom. The impact of the voyage and then of the journey around a very different kind of country was therefore all the greater. South Africa – with its varieties of terrain, race, wealth and culture – was a powerful reminder to Elizabeth of the Commonwealth duties that lay ahead. Both girls were struck by the open spaces: Princess Margaret recalls her sense of the vastness of the country and the contrasts with austerity Britain. ‘There was an amazing opulence, and a great deal to eat,’ she says. She remembers the change from a country still restricted by food rationing, and her delight at the endless series of meals with their abundance of delicacies, including an enticing array of complicated Dutch pastries. Huge fir cones seemed to symbolize the outsize scale of everything they encountered. The South Africans lent them horses, and they rode on the beaches, wearing double felt hats.42

The royal party arrived in Cape Town on 17 February to a tumultuous welcome that banished fears of republican hostility. There was a glittering state banquet the same night. Next day, Lascelles wrote home that while he had never attended a more dreary and miserable dinner in thirty years of attending public functions, the Royal Family seemed to enjoy it, especially the princesses. ‘Princess E[lizabeth] is delightfully enthusiastic and interested,’ he noted; ‘she has her grandmother’s passion for punctuality, and, to my delight, goes bounding furiously up the stairs to bolt her parents, when they are more than usually late.’43 The plan was to bring the British Monarchy into direct contact with every part of the Union – in the words of the tour’s official souvenir – from the seaboard of the Cape and Natal ‘to areas where African tribes live in peace and security under conditions which still suggest the Africa of history.’44

The royal party slept in a special ‘White Train’ for a total of thirty-five nights, travelling to the Orange Free State, Basutoland, Natal and the Transvaal, and then to Northern Rhodesia and Bechuanaland. South Africa was a society rigidly divided on racial grounds: but it did not yet have strict apartheid laws, and the royal party met people from different communities, even attending a ‘Coloured Ball’. The King’s daughter attracted particular attention. Africans shouted from the crowds ‘Stay with us!’ and ‘Leave the Princess behind!’45 The presence of British royalty also aroused keen interest in the small, enclosed white South African world, dominating popular entertainment. At a huge civic ball held in Cape Town the night following their arrival, five thousand guests danced to a fox-trot composed in honour of Elizabeth, called ‘Princess’. The tune accompanied a song which became the catch of the season. ‘Princess, in our opinion,’ went its loyal refrain, ‘You’ll find in our Dominion/Greetings that surely take your breath,/For you have a corner in every heart,/Princess Elizabeth’.46 Elsewhere, there were other musical tributes. At Eshowe, Zulu warriors pounded out the ‘Ngoma Umkosi,’ the Royal Dance before the King. One verse was omitted at the last minute: ‘We hear, O King, your eldest daughter, Princess Elizabeth, is about to give her heart in marriage, and we would like to hear from you who is the man, and when this will be.’47 On 1st April, close to the end of the tour, the not unwelcome or unhelpful news came through of the death of King George of Greece. Lascelles reported home that while there would be a week’s court mourning in London, no notice at all would be taken ‘by anybody out here because we haven’t any becoming mourning with us – a typical Royal Family compromise!’48

At East London, the second city of Cape Province, Elizabeth had to open a graving dock – it was a windy day, and she had to struggle to keep her hat on, her dress down, and her speech from blowing away.49 For much of the trip, however, the princesses’ most demanding duty was to walk behind their parents at ceremonies or sit beside them at displays. It was a long time to be away, on holiday yet constantly on show – and out of touch with ice-bound Britain, where Philip, at his naval base, lectured his students in his naval greatcoat and by candlelight, because of the fuel crisis. According to below-stairs gossip, spread by Bobo MacDonald, who had graduated from children’s nursemaid to become the Princess’s maid and dresser, ‘Elizabeth was very eager for mail throughout the tour, and so was Philip.’50 She also wrote to other friends. Lord Porchester, for instance, received letters from her wherever she went. She wrote vividly, about the tour and meeting Smuts, but also about home. In one letter she asked about her horse, Maple Leaf.51

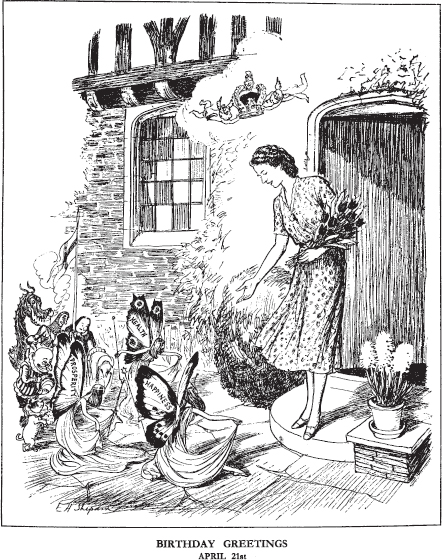

The passivity, however, did not last until the end of the tour. The Royal Family’s departure date was fixed for 24 April. Princess Elizabeth’s twenty-first birthday fell three days earlier – a happy coincidence of timing which enabled the South African government to make it the climax of the visit. It could scarcely have been celebrated on a more elaborate, and extravagant, scale. As a token of the importance Smuts attached to the royal tour, 21 April was declared a public holiday throughout the Union. In addition, the royal birthday was marked by a ceremony, attended by the entire Cabinet, at which the Princess reviewed a large contingent of soldiers, sailors, women’s services, cadets and veterans; by a speech given by the Princess to a ‘youth rally of all races’; by a reception at City Hall in Cape Town; and by yet another ball in the Princess’s honour at which General Smuts presented her with a twenty-one-stone gemstone necklace and a gold key to the city.

The Royal Family made its own most dramatic contribution to the day’s events in the form of a broadcast to the Empire and Commonwealth by Princess Elizabeth, which became the most celebrated of her life. The author was not the Princess, but Sir Alan Lascelles, a straight-backed, hard-bitten courtier, not given to emotionalism – though with a sense of occasion and (as his memoranda and diaries reveal) a lucid, if somewhat old-fashioned, literary style. The speech was both a culmination to the tour, and a prologue for the Princess.

When Princess Elizabeth was consulted in the White Train near Bloemfontein during the preparation of a draft, according to one account, she told her father’s private secretary, ‘It has made me cry’. The effect on many listeners and cinema-goers was much the same as they heard or later watched the solemn young woman making her commitment, like a confirmation or a marriage vow. That her message came from a problematic dominion added to the impact of words which already sounded archaic, and a few years later might have seemed kitsch, yet which seemed strangely to capture the moment. The effect was the more surprising because Lascelles had made no concessions to populism, and had not attempted to write the kind of speech a young woman might have delivered, if the thoughts had been her own.

Punch, 23rd April 1947

‘Although there is none of my father’s subjects, from the oldest to the youngest, whom I do not wish to greet,’ the Princess read from her script, ‘I am thinking especially today of all the young men and women who were born about the same time as myself and have grown up like me in the terrible and glorious years of the Second World War. Will you, the youth of the British family of nations, let me speak on my birthday as your representative?’ She quoted Rupert Brooke. She spoke of the British Empire which had saved the world, and ‘has now to save itself,’ and of making the Commonwealth more full, prosperous and happy. Thus far, her speech belonged alongside other truistic utterances forgettably spoken by royalty when required to address the public. It was the next part that took listeners by surprise. Unexpectedly, she changed tack, launching into what amounted to a personal manifesto, that combined two themes of Sir Henry Marten in his tutorials – the Commonwealth, and the importance of broadcasting: