Полная версия

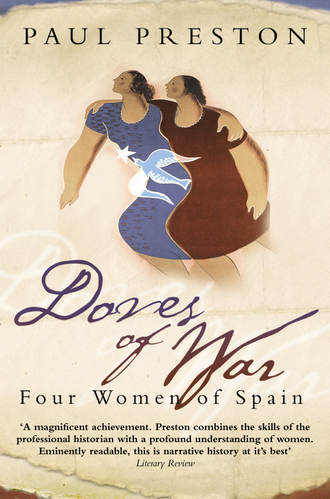

Doves of War: Four Women of Spain

Ecstatically happy to be spending time with Touffles, she had no desire to return to the hospital at Jérez. However, her views were somewhat altered when she came face to face with the arrogantly sexist mentality of the Andalusian aristocratic señorito. Pip and the family went to Seville to stay at the Hotel Cristina, which was ‘crammed full of Germans on leave’. Touffles met up with his Luftwaffe comrades and announced that they were off to a brothel. ‘Of course it is damn stupid of me to mind as it won’t be the first or last time he sleeps with a tart but if he liked me the weeniest bit the way I want him to, he could not have told me he was going to without a qualm. However, who cares. I’m damned if I’m going to. I knew he was not in the least in love with me before so it does not make any difference. Oh hell and damn.’ When he and his German cronies did the same on the following night, she decided that she would rather be at the front nursing. She did not know, of course, whether he did anything more than play the piano and dance.60

Feeling rejected by Ataúlfo, she began to get involved in her hospital work. On 10 November, she attended her first operations which she found enthralling. Touffles went back to his unit on the next day, leaving her ‘with that grim feeling of emptiness and the awful wartime pessimism of wondering at the back of my mind whether I will ever see him again’. One and all continued to enquire as to when she would marry him. She wrote in her diary: ‘But why bother, at this very moment he is almost certainly tootling around Seville with a tart but why should I care. Of course I do but it is very stupid.’ She was finding some consolation in nursing. She loved the work although ‘I am beginning to loathe the Moors. They are so tiresome always quarrelling and yelling at one. It makes me mad to have a lot of filthy smelly Moors ordering me about.’ On the eve of her twenty-first birthday, she wrote: ‘I feel awfully small and young tonight. In a new country talking a strange language and only understanding half of what is said to me, doing a new kind of work amongst new people and about to prance off on my own to the middle of the war. Sometimes I feel an awful long way from home but who cares. It is the first adventure I have ever undertaken and so far I love it.’ When Princess Bea returned to England on 20 November, Pip went back to Jérez where she waited anxiously for her nursing examination. She was keen to get to the front – ‘I am tired of waiting around doing nothing much. I want action.’ Every day, her diary recorded her anxiety to be off to war. However, this required the permission of Mercedes Milá, the head of the Nationalist nursing services. The ordeal of the examination on 1 December passed off less traumatically than she had feared. In fact, she was amazed by how much she was left to do in the hospital without supervision.61

Her social life was hectic; late nights consisting of cinema, dinner, protracted dancing and drinking. On 6 and 7 December, she was given a tour around the German battleship Deutschland which she thought ‘a lovely boat’. On 20 December, Touffles and one of his German friends took her for a spin in a Junkers 52 bomber. Despite the distractions, she was becoming deeply impatient with Mercedes Milá’s failure to respond to her request to go to the front. She was all the more unsettled because of rumours about major action on the Aragón front – an echo of the Republican offensive against Teruel. As her Spanish improved and she got to know more people, her social life was coming to resemble her life in London albeit on a narrower scale. She had a couple of superficial flirtations, her blonde hair and blue eyes – and probably her plumpness too – making her very attractive to Spanish men. Finally, knowing that Princess Bea was in Burgos, she decided to leave the hospital at Jérez and make the hazardous eleven-hour 1000-kilometre car journey to join her for Christmas. It was a courageous – or irresponsible – initiative since attractive young women travelling alone in Spain were usually at risk from sexually frustrated soldiers. With typical self-reliance, she coped with running out of petrol on remote roads and the car’s sump springing a leak.62

When, after driving for two days, she finally arrived at Burgos on 23 December, she could not find Princess Bea and was desperate to have come so far only to be all alone. Princess Bea had moved on to the Palacio de Ventosilla at Aranda de Duero where her family would be staying. This was because the front-line units of the Nationalist air force were being regrouped as the Primera Brigada Aérea Hispana at Aranda, alongside the Italian Aviazione Legionaria in Zaragoza and the German Condor Legion in Almazán, the walled medieval town due south of Soria. General Alfredo Kindelán, with overall command over all three forces, had established his headquarters at Burgos. It was Pip’s good fortune to get a room in the hotel where General Kindelán’s family were staying. They told her that Mercedes Milá planned to send her to a front-line hospital. There was a terrible scare when word was brought to the hotel that Álvaro de Orléans had crashed. His Italian wife Carla Parodi-Delfino was hysterical and Pip had to calm her down. She then went on to the Palacio de Ventosilla. To the relief of Álvaro’s escape, there was added the dual pleasure of resolving her future as a nurse at the front and of seeing Ataúlfo. Touffles told her that she was much thinner and very beautiful. However, that delight was dampened by Princess Bea, who knew that Pip was in love with him. The Infanta told her the first of a series of slightly conflicting stories by way of breaking to her gently that Ataúlfo would never marry her. She said, rather implausibly, that he would never recover from having his heart broken by the daughter of Alfonso XIII, Beatriz. The romantic in Pip was both intrigued and devastated to be told by Princess Bea that Touffles was so affected by this that she was ‘afraid he will never fall in love or get married and will just get more and more the young man about town and have mistresses’.63

Meanwhile, the men of the family were flying bombing missions against the Republican forces that were closing in on Teruel. The proximity to the war was beginning to affect Pip. ‘It really is an awful life when you know your friends are risking their lives every single day and every time you say goodbye or just goodnight you think you may never see them again.’ Her diaries reflected her links with senior officers of the Nationalist air force. She felt an ever closer identification with the cause: ‘Today [28 December] we lost one machine and shot down seven reds.’ Today [30 December] they brought down eight Reds, four Curtis, two Martin bombers and two others and we did not lose one. Good work!’ ‘We shot down eleven Reds today [4 January 1938].’ ‘We shot down eight Reds today. The right spirit. [5 January 1938].’ The strain of seeing Touffles only fleetingly as he often popped in between flights was trying her nerves and increased her determination to get to the front line. Her wish was granted, in mid-January, by a telegram instructing her to go to the hospital at Alhama de Aragón, southwest of Zaragoza on the road to Guadalajara. She was reluctant to leave the Orléans family but a move was inevitable because of a reorganisation of the Nationalist air force. Prince Ali’s air force unit (escuadra) of Savoia-Marcchetti 79s was moving to Castejón while Ataúlfo’s Condor Legion bomber unit was moving to Corella. Both Castejón and Corella were between Alfaro and Tudela in Navarre and Princess Bea was going to Castejon in order to set up a house for her husband and son.64

In fact, when the orders came, the entire household was plunged into various forms of colds and influenza. The worst hit was Ataúlfo and Pip decided to stay on and nurse him. However, proximity to her loved one did not bring happiness.

I am in the depths of depression and so nervous that I don’t know what to do with myself. I can’t sleep and have not done so for three nights which is not surprising when I have to spend my whole day keeping a firm grip on myself not to appear to be in love with Ataúlfo. I don’t know whether I am getting less controlled, more frustrated or more alone but it is pure hell whatever it is and leaves me in a state of being unable to sleep, unable to eat and feeling miserable.

The imminent upheaval meant that Pip would have to leave anyway. The malicious gossip about her relationship with him made it impossible for her to stay and nurse Ataúlfo without Princess Bea in the house as chaperone. Pip’s misery was dissipated by a meeting with Bella Kindelán, the general’s daughter, who was a nurse at Alhama. When Bella told her that it would be possible to go from Alhama with a mobile unit right up to the front, she cast off her melancholia and threw herself into nursing.65

By 24 January 1938, Pip’s prolonged Christmas holidays were over and she was ensconced along with the other nurses in the grim hotel in Alhama de Aragón which partly served as the local hospital. It was bitterly cold and depressing. The winter of 1937–8 was one of the cruellest Spain had ever suffered, the bitter cold at its worst in the barren and rocky terrain of Aragón with temperatures as low as –20° centigrade. Pip was missing Ataúlfo and there was nothing for her to do. She had been joined by Consuelo Osorio de Moscoso, the daughter of the Duqesa de Montemar. Alarmed at the prospect of spending time in their tiny unheated room, they impetuously decided to take matters into their own hands and go to Sigüenza where Consuelo knew some doctors. They hoped thereby to get to the front. However, when they reached the emergency hospital there, they were told that the front-line mobile units were fully staffed and had very few wounded. On their return to Aragón, they fell into an even worse gloom. ‘There is nothing to do anywhere. The war seems to have paused and no one wants nurses.’66 This was far from true. The battle for Teruel was still raging. Within ten days of the city falling into the hands of the Republic, the advancing Nationalist forces became the besiegers. The scale of the fighting can be deduced from Franco’s remark on 29 January to the Italian Ambassador that he was delighted because the Republic was destroying its reserves by throwing them into ‘the witches’ cauldron of Teruel’.67 Astonishingly, this was not reflected in the traffic through the hospital at Alhama where Pip was now assigned to a ward.

Much of her work was routine and unpleasant. One of her patients had a spinal injury – ‘as he has lost all sense of feeling, he pees in his bed and we have to change the sheets which is both difficult and messy as he can’t move at all, also he has no pyjamas and boils all over his bottom which is most unappetising. As for the other part of him, it is definitely an unpleasing spectacle which somehow always manages to be just where I want to take hold of a sheet.’ However, the routine was short-lived. On 28 January, Mercedes Mila arrived to assign nurses to other hospitals. Consuelo and Pip pestered her to be sent to the front. At first, their pleas fell on deaf ears and the head of the Nationalist nursing services said that Pip was too young to be given responsibility in a dangerous position. However, with more senior nurses reluctant to go to the front, they were picked with three others to go to Cella, eight kilometres from Teruel, the nearest hospital to the front. Pip was excited and immediately thought of Ataúlfo, ‘I shall see them all going over to bomb everyday perhaps. I can’t wait to go, my spirit of adventure is aroused.’ Although she was aware the hospital might be shelled and bombarded, her principal concern was whether her nursing skills would be adequate when the lives of the seriously wounded were at stake.68

After a perilous journey on mountain roads, Pip and Consuelo reached the bombed-out village of Cella. Their welcome was muted since there was neither food nor accommodation to spare. The officers refused to believe them when they said they would willingly sleep on the bare floor. They were eventually put in a room with three others, without proper bedding or window panes and only the most minimal sanitation. Pip’s spirit of adventure and her country background helped her make light of the situation: ‘The town itself is crammed with soldiers and mules, and ambulances come and go in a continuous stream. I am so enchanted with the place that I long to stay but we are terribly afraid that they will send us back when the others come as they have precedence over us. It is a shame as they will hate the discomfort and dirt and all and we don’t mind it.’ Indeed, she was anxious to join a mobile unit leaving for a position at Villaquemada, even nearer to the front line. Just when Pip thought that she would have to go back to Alhama, a need arose for two nurses so she and Consuelo were able to stay. They also found accommodation in a peasant farmhouse. Possessing a car made a colossal difference, since she could drive to nearby towns to shop for household necessities to make their room more comfortable and also for food. In the operating theatre itself, Pip was shocked by the doctor’s ignorance of basic procedures of hygiene, ‘His ideas of antisepsia were very shaky and it gave me the creeps to see the casual way they picked up sterilised compresses with their fingers.’ She was equally alarmed to see their peasant hostess dipping into their food fingers ‘black with years of grime’.69

The Nationalists were mounting a major attack on Republican lines at Teruel and Pip’s medical unit was moved nearer the front. On 5 February, she was in attendance for ‘one elbow shrapnel wound, three amputations, two arms and one leg, two stomach wounds, one head and one man who had shrapnel wounds in both legs, groin, stomach, arm and head. They were vile operations. The stomach ones were foul. One had to be cut right down the middle and his stomach came out like a balloon and most of his intestines; the other had a perforated intestine so had all his guts out, looking revolting.’ Things were made more difficult by the fact that the doctor for whom she worked was both incompetent and perpetually irritable. ‘It is perfectly grim having to work as operation sister to a man one does not trust, who is brutal and shouts at one all the time. It is nerve-wracking and leaves me all of a flop.’ Pip discovered that she had type O blood and therefore could give blood for transfusions. At massive cost to both sides, the battle swayed back and forth until finally, on 7 February 1938, the Nationalists broke through and the Republic lost a huge swathe of territory and several thousand prisoners as well as tons of valuable equipment. Pip was delighted: ‘The news of the war last night was stupendous. We have advanced to Alfambra, twenty kilometres in two days, taking fifteen villages, 2,5000 prisoners and 3,000 dead, not to mention lots of war material.’ It was the beginning of an inexorable advance which in two weeks would lead to the recapture of Teruel on 22 February, the capture of nearly fifteen thousand prisoners and the loss of more equipment.70

The appalling conditions in the operating theatre could be mitigated by the trips in the car. Only with considerable resourcefulness had she kept it on the road, changing wheels, repairing punctures and getting it started in sub-zero temperatures. She drove to Alhama to collect her belongings which had been sent there from Aranda. Having a gramophone and lots of new records sent out by her family made life all the more tolerable. She also was able to see some beautiful countryside. Buying presents for the family with which she was billeted, she was surprised at their reaction – ‘Unlike English poor class they were so proud they would hardly accept them.’ The gruesome sights that she was seeing each day in the operating theatre were so distressing that she needed every possible distraction. Her diary faithfully recorded the details of horrendous surgical interventions often carried out without anaesthetic. After an operation on a young boy wounded in the stomach only three days after being conscripted, she broke down and cried. ‘He was so white and pathetic with an expression of such pain and sorrow and he never made a sound.’ The accumulated horrors were beginning to get to her and she began to question the wisdom of coming to Spain. However, by the following day she had recovered her usual good spirits. A lunch which would have been the envy of the entire Republican zone helped. It consisted of ‘poached eggs, tinned salmon with mayonnaise, albóndigas (meatballs in rich gravy) and fried potatoes, cheese and chocolate pudding, not to mention foie gras and oporto as an aperitif and coffee and coñac to finish with’. Even better was an unexpected – and poignantly short – visit from Touffles. Despite the cold, in a room with no panes in the windows, having to sleep fully dressed in tweeds, she sewed and ironed and maintained her essential cheerfulness. Inevitably she faced many of the same problems as Nan Green and the front-line nurses on the Republican side. ‘The thought of a hot bath, a comfortable bed, a good meal that we did not have to cook ourselves or watch cooking and a w.c. instead of a pot seemed distinctly pleasant.’71

On 17 February, there was a big Nationalist push and Pip went to watch the battle from a German anti-aircraft battery. ‘The noise was incredible, a continual roar like thunder with intermittent different-toned bands. The sky was full of aeroplanes shooting up and down the Red trenches and the whole landscape all around was covered with pillars of smoke.’ ‘At about 11.30 the bombers began to arrive and came in a continual stream for hour after hour till the Red lines were black with the smoke of the bombs.’ Pip thought it was ‘the most thrilling thing I have ever seen’. The counterpart to the exhilarating sights was an increase in traffic in the operating theatre. Her compassion for the wounded and dying was unrelated to any analysis of the reasons for the war. Indeed, by 20 February, she was exhilarated by the possibility of going to see Nationalist troops entering Teruel. Although not allowed to enter the city, she and her fellow nurses found a vantage point from which, ‘to our great joy’, they watched Nationalist aircraft bombing the Republicans retreating towards Valencia.

Yet on the next day, after ten hours’ non-stop effort in the operating theatre, she could write that ‘it is demoralising to live in an eternal whorl of blood, pain and death’. Reflecting on the daily deaths of casualties in the operating room, she wrote: ‘I don’t know how there is anyone left.’ There was still house-to-house fighting in Teruel. On 22 February, awakened by bells ringing for the Nationalist capture of the city, she walked through the battered remains of the city. ‘I didn’t see a single whole house, they are all covered in bullet holes and shot to bits by cannons with great gaping holes from air bombardments.’ In the midst of the rubble, she found an undamaged grand piano in a bar and played tunes while the soldiers stopped looting in order to dance. She rejoiced at the Nationalist advance that was chasing the retreating Republicans to the south. Three thousand prisoners were taken and two thousand dead according to the official radio. The next day, back in the hospital, she was covered in blood from the operations and, on the day after that, back in Teruel. She was flushed with excitement by a Republican artillery bombardment – ‘I admit I was terrified myself but I like being frightened.’ Her emotional highs and lows were intense.72

Unsurprisingly given the daily horrors that she was facing, Pip was outraged to learn from her cousin Charmian that her brother John disapproved of her being in Spain and was determined to get her back home. ‘Bloody interfering nonsense. I should like to see him try anyhow.’73 In mid-February, John did come to Spain in search of Pip. Since she was on duty in the midst of the Battle of Teruel, he did not get to see her. He was rather shocked by this since, as he recalled later, ‘I don’t think that my parents had visualised anything more than her being in some base camp, helping a bit with bandages.’ John Scott-Ellis did meet Peter Kemp who gave him news of Pip. He also met Ataúlfo and struck up a friendship with the German pilots of his unit. Shortly afterwards he continued his journey on to Munich. When John spoke to his wife’s family there, they categorically refused to believe that he had met German pilots in Spain because, after all, Hitler had declared that there were none.74

Pip’s diary is remarkable for the wealth of detail with which she described her days. It is therefore all the more puzzling that her future husband, José Luis de Vilallonga, claimed to have bumped into her in Teruel, some hours after the recapture of the town by the Francoist forces. No such incident is mentioned by Pip in her diary, in which there are no gaps during this period. Nevertheless, the ‘meeting’ is described with a wealth of salacious detail in his memoirs. Entertainingly written, like all his work, this account is full of the most unlikely particulars. After one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, fought in sub-zero temperatures, the Republicans had to give up their costly defence of the provincial capital captured on 8 January. They retreated on 21 February 1938, when Teruel was on the point of being encircled. According to Vilallonga, at the time, just eighteen,75 he was wandering around the recently captured city in search of his father, the Barón de Segur, a staff officer with the great cavalryman General José Monasterio Ituarte. ‘And suddenly, as I turned a corner, I saw her. It was like an advertisement torn from Harper’s Bazaar. A tall, blonde woman, in an immaculate white nurse’s uniform with a great blue cape that reached down to her feet. Around her neck, curled with studied negligence, she wore a Hermés foulard that brought out the clear blue of her eyes.’ José Luis recalled being entranced by this vision of loveliness. Allegedly, she was smoking while leaning nonchalantly on the bonnet of a new ambulance with a London number plate. All around, the aftermath of the battle in the streets could be seen. A woman knelt next to the still-warm corpse of a man whose throat had been cut by one of the Moorish mercenaries. While excited Moors were looting houses, carrying out the most bizarre objects from mattresses to bidets, Pip is described as simulating total indifference to what was going on around her, an oasis – or perhaps a mirage – of calm in the midst of chaotic slaughter and mayhem.76

The Pip of this account has nothing of the girlish spontaneity and good-hearted sincerity that speaks out from every page of her diary. When José Luis de Vilallonga walked up and began to speak to her, in English he later claimed, she offered him a cigarette then slid a silver hip flask from under her cape and invited him to take a swig of Beefeater gin. She then said peremptorily, ‘Have lunch with me’ and introduced herself. ‘I’m Priscilla Scott-Ellis, but all my friends call me Pip. I’m half-Welsh, half-Scottish, but of course I was born in London.’ After a short pause, she announced, ‘My mother is Jewish.’ It is highly questionable that she would say any such thing but José Luis, who seems to be transferring many of his attitudes onto her, repeatedly makes reference in his works to her Jewish blood. She then opened the chest on the side of the ambulance, rummaged around in a pile of packages and emerged clutching a tin of foie gras and a bottle of excellent claret. For pudding, she managed to come up with a packet of Fortnum and Mason chocolate liqueurs. She explained how she came to be involved in the Spanish Civil War, commenting: ‘Most of my friends and some of my relatives have joined the Republicans and the Communists.’ Just as she was assuring him that the British Government would never help the Republic on the grounds that the British always support the forces of order, they heard the sound of shots from behind a nearby church. ‘They’re shooting people. That means that the Falangists have arrived. They are always the ones who come to shoot the reds left alive in the cities occupied by the Army.’ ‘The forces of order,’ commented Vilallonga sarcastically. ‘No,’ she replied with devastating insight, ‘just people who like killing. They’re just loud-mouthed rich kids who say they are fighting for the workers but, as soon as they find one alive, they put him up against a wall and shoot him.’