Полная версия

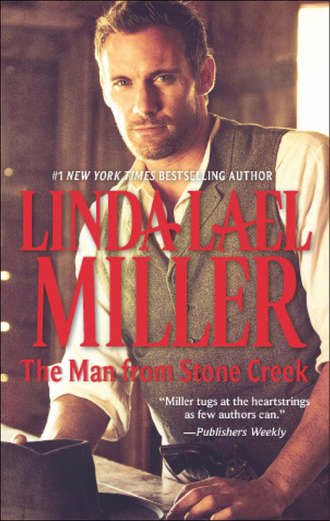

The Man from Stone Creek

Sam opened his mouth to answer, but before he could get a word out, Terran cut him off. “She’s over to the schoolhouse, giving Violet Perkins a bath!” he crowed.

“Teaching a hygiene lesson,” Sam corrected quietly.

“Well,” huffed the Hawk Woman, “it’s about time somebody look that child in hand.”

“Yes,” Sam said, opening the cash register drawer to tally the funds on hand. “It is about time.”

The woman blinked.

Sam silently congratulated himself on a bull’s-eye.

By ten-thirty, he’d taken in four dollars and forty-eight cents, and made careful note of every transaction, so Maddie couldn’t say he’d fouled up her books. Then, figuring the hygiene lesson ought to be over, and Violet decent again, he dispatched Terran and young Ben Donagher to the schoolhouse to find out.

When they came back, Maddie was with them, the front of her dress sodden and her hair moist around her face. He couldn’t rightly tell if that sparkle in her whiskey eyes was temper or satisfaction with a job well done.

“I see my store is still standing,” she remarked.

Sam grinned. “I trust my school has fared as well,” he parried, reaching for his hat.

“You’ll have to empty the bathtub yourself,” Maddie said, taking her storekeeper’s apron down off a peg and donning it. “Violet fairly gleams with cleanliness. One of the other girls aired out her dress while she was soaking.”

Sam sent the boys trooping back to the schoolhouse, lingering to take out his wallet. “Next time Violet comes in the store,” he said, laying a bill down on the counter, “you outfit her with a new one. Say there was a drawing and she won.”

Maddie regarded him solemnly. He still couldn’t tell whether she was pleased with him or wanted to peel off a strip of his hide. “You lie very easily, Mr. O’Ballivan,” she said.

Well, that answered one of his questions. “Kids like Violet run into more than their fair share of humiliation, it seems to me,” he replied. “If a lie can spare them embarrassment, then I’m all for it.”

She had the good grace to blush.

He waited until he’d reached the doorway before putting on his hat. “We’re due at the Donaghers’s supper table at seven o’clock,” he reminded her. “Best have Terran hitch up that buckboard you use for deliveries unless you want to ride two to a horse.”

Maddie put the bill he’d left on the counter into the cash register and headed for a display of calico dresses, probably to choose one for Violet. “We’ll take the buckboard,” she said without looking at him.

Sam smiled to himself as he closed the door behind him.

Damn, he thought. It would have been a fine thing to share a saddle with Miss Maddie Chancelor. A fine thing indeed.

* * *

SCHOOL HAD LET OUT for the day and Sam was seated at his desk, going over the map Vierra had given him the night before, when a small, impossibly thin woman stepped shyly over the threshold. She wore a bonnet and a faded cotton dress, and he knew who she was before she introduced herself.

He refolded the map, set a paper weight on top of it, and stood. “Sam O’Ballivan,” he said by way of introduction, and added a cordial nod.

“Mrs. John Perkins,” Violet’s mother responded, lingering just inside the open door.

“Come in,” Sam urged when she didn’t show any signs of moving.

She hesitated another moment, then thrust herself into motion. He noticed then, as she approached, that she was carrying a basket over one arm, filled with brown eggs. She set the whole works on his desk, straightened her spine, and looked up at him.

“I guess my Violet had a bath today at school,” she said.

Sam waited. She’d brought him eggs, which might be construed as a peaceful gesture, but you never knew with women. They could be crafty as all get-out. Most of the time, when they said one thing, they meant another. They expected a man to learn their language and converse in it like a native.

Mrs. Perkins drew herself up to her full, unremarkable height, the top of her head barely reaching Sam’s shirt pocket. Under the brim of that bonnet, her eyes spoke eloquently of her discouragement and her fierce pride. “I came to thank you for making a lesson of it,” she said. “Violet’s real pleased that she was chosen for an example.”

“Violet,” Sam said honestly, “is a fine girl.”

Tears brimmed along the woman’s lower lashes and her pointed little chin jutted out. “It’s been so hard since John was killed. I love my Violet, I truly do, but betwixt keepin’ food on the table and a roof over our heads, I fear I’ve let some things go.”

Sam wanted to lay a hand on Mrs. Perkins’s bony shoulder, but it would be a familiar gesture, so he refrained. “Any time you want the use of my bathtub,” he said awkwardly, “you just say the word. I’ll fill it with hot water and make myself scarce.”

Mrs. Perkins blinked, sniffled, looked away for a moment. “That’s right kind,” she said. “I can do better by my girl, and I will, too. I swear I will, Mr. O’Ballivan. Short of goin’ to work for Oralee Pringle, though, I can’t think how.”

Sam took an egg from the basket and examined it as thoroughly as if he’d never seen one before. “I do favor eggs,” he said. “I’d buy a dozen from you, every other day, and pay a good price for a chicken now and then, too, if you’ve got any to spare.”

“Them eggs was meant as a present,” Mrs. Perkins said, but she looked hopeful. “I sell a few, but folks around here mostly keep their own chickens.”

“Bring me a dozen, day after tomorrow,” Sam replied. “I’ll give fifty cents for them, if you throw in a stewing hen every now and then.”

For the first time since she’d entered the schoolhouse, Mrs. Perkins smiled. It was tentative, and her eyes were wary, as if she thought he might be playing a joke on her. “That’s an awful lot of money, for twelve eggs and a chicken,” she said carefully.

“I’m a man of princely tastes,” Sam replied. His mouth watered, just looking at those eggs. He’d have fried half of them up for a feast if he wasn’t dining at the Donagher ranch that night.

It would be interesting to see if those two fools he’d locked in that Mexican outhouse showed up at the table, and more interesting still to pass an evening in Maddie Chancelor’s company.

“You want that chicken plucked and dressed out, or still flappin’ its wings?” Violet’s mother asked.

Sam took a moment to shift back to the present moment. “It would be a favor to me if it was ready for the kettle,” he said.

Mrs. Perkins beamed. “Fifty cents,” she said dreamily. “I don’t know as I’ll recall what to do with so much money.”

Sam took up the eggs. “I’ll put these by, and give you back your basket,” he told the woman. She waited while he performed the errand, and looked surprised when he came back and handed her two quarters along with the battered wicker container. “I like to pay in advance,” he said as casually as he could.

To his surprise, she stood on her tiptoes, kissed him on the cheek and fled with the basket, fifty cents and the better part of her dignity.

CHAPTER FIVE

MADDIE DROVE UP in front of the schoolhouse promptly at six o’clock that evening, the last of the daylight rimming her chestnut hair in fire. She managed the decrepit buckboard and pitiful team as grandly as if she’d been at the reins of a fancy surrey drawn by a matched pair of Tennessee trotters.

Sam lingered a few moments on the steps of that one-room school, savoring the sight of her, etching it into his memory. Once he left Haven for good, and married up with Abigail, as it was his destiny to do, he wanted to be able to recall Maddie Chancelor in every exquisite detail, just as she looked right then, wearing a blue woolen dress, with a matching bonnet dangling down her straight, slender back by its ribbons.

He felt a shifting, sorrowful ache of pleasure, watching her from under the brim of his hat, and the recalcitrant expression on her face did nothing to dampen the sad joy of taking her in.

“Well,” she called, after rattling to a shambly stop, “are we going to the Donaghers’ or not?”

Sam bit back a grin, tempted to reach out and give the bell rope a good wrench before he stepped down, announcing to all creation that he was having supper with the best-looking woman he’d ever laid eyes on. But some things were just too private to tell, even though nobody but him would have known the meaning of that clanging peal.

His insides reverberated, just as surely as if he’d gone ahead and pulled that rope with all his might.

“Evening, Miss Chancelor,” he said, approaching the wagon. She’d hung kerosene lanterns on either side of the buckboard, to light their way a little after darkness rolled over the landscape like a blanket, but she’d yet to strike a match to the wicks. She was a prudent soul, Maddie was, and not inclined to waste costly fuel before there was a true need for it.

She showed no signs of letting go of the reins so he could take them. He resigned himself to being driven through the center of town by a lady, and climbed up beside her, swallowing a swell of masculine pride.

“I don’t mind telling you,” she said, “that sitting down at Mungo Donagher’s table is just about the last thing in the world I want to do this evening.”

Sam smiled. The prospect wasn’t real high on his list, either, but there was a possibility he’d meet up with Donagher’s elder sons, and that was the only reason he’d accepted the invitation. Like Vierra, he was already half convinced that Mungo’s boys were involved in the outlaw gang that had been plaguing both the Arizona Territory and the State of Sonora for several years, but he needed proof—a quantity that was most often gathered one small, seemingly unimportant fact at a time.

“Terran told me about Warren Debney,” he said quietly, just to get it out of the way. If he hadn’t spoken up, the knowledge would have remained a gulf between them, and he wanted as little distance as possible.

He felt her stiffen beside him, and she set the buckboard rolling with a hard slap of the reins and a lurch that nearly unseated him, since he hadn’t braced for it. “Terran,” she said, “sometimes talks too much.”

Sam resettled his hat, needing something to occupy his hands, for it was obvious Maddie wasn’t about to surrender the reins. “He said one of the Donagher brothers probably fired the fatal shot,” he went on, slow and quiet. “What do you think, Maddie?”

She was quiet for a long time, so long that Sam feared she didn’t intend to answer at all. Finally, though, she said, “I believe it was Rex. He’s the meanest of the three, and he and Warren had had several run-ins just prior to the shooting.”

“You were with him? Debney, I mean—when he was shot?”

She swallowed visibly, nodded, keeping her gaze fixed on the road into the main part of town. “He died in my arms,” she said, so quietly that Sam barely heard her over the hooves of those worn-out horses and the rattle of fittings.

He wanted to put his arm around her, but he knew it would cause her to pull away, so he didn’t. They rounded a bend and passed the mercantile, then the Rattlesnake Saloon. Charlie Wilcox’s old nag stood out front, patiently waiting to bear him home on its swayed back. “I’m sorry that happened to you, Maddie Chancelor,” Sam said.

“So am I,” she replied.

Sam shifted on the hard wagon seat. “It must be difficult for you—sitting down to take a meal with somebody who might have killed your man. I didn’t know about that when I roped you into coming along, and if you want to change your mind, I’ll understand.”

At long last she looked him in the eye. They were traveling east, with the setting sun at their backs, headed for the river road that led to the Donagher ranch. Sam reckoned that, after a mile or two, they’d have to stop so he could step down and light those lanterns, but for now, all he cared about was whatever Maddie was about to say.

“It makes me nervous when any of the Donagher boys come into the store,” she said frankly. “Just the same, I wouldn’t miss a chance to look them straight in the eye and let them know they’re not fooling me for one moment. They got away with shooting Warren, and stringing up poor, harmless John Perkins, too. Maybe they fooled the law, but they can’t fool God, and they can’t fool me.”

Sam sighed as they passed the row of businesses along the main street, all of them closed up and dark, like Maddie Chancelor’s broken heart probably was. He didn’t care for the idea of her drawing the Donaghers’ attention, taunting them with her suspicions. It was akin to stirring a hornet’s nest with a chunk of firewood.

“You probably ought to stay in town tonight. I’d be obliged, though, for the loan of your wagon.”

To his surprise, and cautious delight, she favored him with a soft smile and a shake of her head. The subtle scent of her lush hair teased his senses. “I guess the team and buckboard would be safe in your keeping,” she said, “and I do appreciate your kind concern. But I’ve looked after myself for a long time, and anyway, the Donaghers wouldn’t dare bother me in Mungo’s presence.” Humor flickered in her brown eyes. “Besides, there is the question of your safety, Mr. O’Ballivan.”

He straightened his spine. “I’m not afraid of any of the Donaghers, or all of them put together,” he said.

“I know that,” Maddie replied. “But there’s one Donagher you’d be wise to look out for, and that’s Undine.”

They were passing out of town, and Sam gave up on the hope that Maddie would change her mind and go back to her quarters above the mercantile, instead of venturing into the snakes’ den, with him. “Undine,” he repeated, confused. Unless the lady had a derringer tucked up the sleeve of her dress, he couldn’t imagine how she’d do him any harm.

“She’s set her sights on you,” Maddie said. “Mungo won’t take kindly to that. He’s mean jealous, and he’d as soon kill any man she takes a fancy to as look at him.”

Sam pondered that bit of information, then took a risk. “Did she ‘take a fancy’ to Warren Debney?” he asked. “Or maybe John Perkins?”

“Warren was dead and buried long before Mungo brought Undine to Haven as his bride,” Maddie said, and her eyes took on a haunted expression. “As for Mr. Perkins, she wouldn’t have given him a second look. But she has taken a liking to you. If you ignore that, it will be at your peril.”

Sam rubbed his chin with one hand, as he often did when he was thinking. He’d shaved for the occasion, and his skin still felt raw from the stroke of the new razor. His new white shirt itched, too, so he shrugged inside it, in a vain attempt to find relief. “You sound mighty certain,” he said at some length, “about Undine’s flirtations being potentially fatal for the object of her attentions, that is. Something must have happened to convince you.”

“It’s just a feeling,” Maddie said, narrowing her wondrous eyes a little upon the darkening road. “Woman’s intuition.”

“I think there’s more to it than that,” Sam persisted.

She met his eyes. “Haven is small. There are plenty of stories going around, and I hear most of them because just about everybody in this part of the territory makes their way to the mercantile on a regular basis. Mungo’s temper is legendary—they say he once beat Landry, the middle son by his first wife, nearly to death for leaving a gate open. Ben—the little one—is a friend of Terran’s, and sometimes passes the night with us if the weather is bad enough that he can’t get home. That boy is terrified of his father—and his brothers, too. I always get the feeling, whenever I’m around him, that there are things he wants to tell me—tell anybody—but he’s afraid to speak up.”

“He was in on dangling Singleton down the well,” Sam said. For the sake of the peace, he didn’t add along with your brother. “I’ve been keeping an eye on Ben, trying to size him up. He’s smart as hell, but he’s skittish, too. Yesterday in class somebody dropped the dictionary and he about jumped out of his hide.”

Maddie bit her lower lip. “I worry about Ben, out there alone with those rowdy men,” she confessed. “Undine seems fond of him, though. If it weren’t for her, I don’t think I’d close my eyes at night for fretting about it. If she were to leave—”

It was all but dark by then, and Sam laid a hand over Maddie’s, where she gripped the reins. “Better pull up,” he said, “so I can light those lamps.”

She complied ably, and he got down to attend to the lanterns. When he climbed back into the wagon box, she surprised him by handing over the reins.

“What else can you tell me about Mungo and his boys?” he asked mildly when they’d traveled a ways. The river twisted and wound alongside the narrow track, whispering stories of its own.

“They own just about everything in Haven, save Oralee Pringle’s saloon,” she said, sighing. Then, with reluctance, she reminded him, and maybe herself, “Including the general store.”

In the beginning, Sam had believed the store was Maddie’s, taken comfort in the idea that she had a way to get along, to provide for herself and Terran. Singleton had said, that first day, that they didn’t have any other family, and he’d assumed she must have inherited the mercantile from her father. Then she’d said she ran the place for somebody else and had to account to Mr. James, the banker. It hadn’t occurred to Sam that that “somebody else” might be a Donagher.

“I work for Mungo Donagher,” Maddie affirmed, sounding as if she’d just awakened from a bad dream only to find out it was real. “Mr. James, over at the bank, oversees the accounts, like I told you, but it’s Mungo who pays my wages.”

“I don’t suppose you can afford to offend him by accusing his boys of gunning down Warren Debney,” he said when he’d considered for a while.

“I’m not so sure he didn’t do it himself,” Maddie admitted softly, and when she looked up at Sam, he saw bleak resignation in her eyes. He’d have done or said just about anything, right then, to give her ease, but nothing came to mind.

“What makes you say that?” Sam asked when he’d absorbed the statement.

Maddie was silent for a long time and Sam was beginning to think he’d asked one question too many when she finally answered. “Until he brought Undine home from Phoenix,” she said, “Mungo was courting me. He told me if I went ahead and married Warren, I’d have to give up managing the mercantile.”

Something elemental and dark rose up within Sam, and he was a while putting it right. He felt as protective and as possessive of Maddie as if he’d been the one about to put a ring on her finger instead of Warren Debney. “And if you’d given in? Married Mungo instead of Debney?”

“He’d have signed the store over as a wedding gift,” Maddie recalled, frowning. “A plaything, as he put it.”

It made Sam’s gorge rise, to think of Mungo Donagher touching Maddie, let alone bedding her. “Some women,” he said in his own good time, “would have taken the old coot up on the bargain.”

Maddie pulled her shawl up around her shoulders, against the chill of the evening, and Sam thought she moved a fraction of an inch closer to him. “I’d sooner take up residence upstairs at the Rattlesnake Saloon. It amounts to the same thing.”

Sam hadn’t thought any image could be worse than Maddie throwing in with the head of the Donagher clan, but sure enough, she’d come up with one. He set his jaw and tightened his hold on the reins. At the rate these horses were traveling, they might be on time for breakfast.

* * *

THE LIGHTS of Mungo Donagher’s long, rustic house winked in the thick purplish gloom of the night. Normally, Maddie would sooner have been thrown to the lions than set foot in that place a second time, but with Sam O’Ballivan beside her, she actually enjoyed the prospect. She even hoped she would come face-to-face with Rex Donagher; she’d find a way to let him know what she thought of him and those cur brothers of his, even though she dared not insult their father. Without her job at the mercantile, she and Terran would be worse off than Violet Perkins and her mother, Hittie.

Mungo himself was waiting to greet them when they pulled up in the dooryard. The ground was unadorned by flowers and there were no curtains at the windows. Had Maddie lived in such a house, she would have planted peonies and climbing roses first thing, even if she had to carry water from the river to make them thrive. Her own plants were spindly and pitiful, and wherever she moved them, shadows followed, robbing them of light.

Mungo’s stance was stern and his countenance unwelcoming. Maddie knew it was Sam he mistrusted, not herself, but she felt a quiver of unease in the pit of her stomach just the same. She’d warned Sam, though, and that was all she could do.

He climbed down from the wagon box, extinguished the lamps to save kerosene for the ride back to town, and then extended a hand to Maddie. All that time, Mungo neither moved nor spoke. She felt his displeasure, invisible but real, roiling in the space between them.

“Evening, Mr. Donagher,” Sam said as cheerfully as if Mungo had been watching the road in eager anticipation of their arrival. “Mind if I unhitch these horses and let them graze on some of this grass?”

Before Mungo could form a reply, Undine slipped through the open doorway behind him, holding up a lantern that glowed almost as brightly as her smile.

“Supper’s ready to be served,” she called. “I cooked it myself, too.”

In the spill of light from Undine’s lantern, Mungo’s face looked hard.

Maddie shivered inwardly and wished it wouldn’t be baldly impolite to fetch her shotgun from underneath the wagon seat and bring it right inside with her. “I’m half starved,” she answered, because Sam didn’t say a word—he was busy unhitching the team—and neither did Mungo.

Undine blinked, as though she hadn’t taken notice of Maddie until that moment. “That’s fine,” she said without conviction. “You come on inside now, Maddie. Let the men tend to those horses.” She nudged Mungo with one elbow and he finally moved.

Maddie glanced in Sam’s direction, and was strangely stricken to see that he’d paused in his work to gaze thoughtfully in Undine’s direction. In that moment, she would have given her meager savings, stashed in a coffee tin under a loose floorboard in her bedroom, to know what was going through his mind.

It irritated her that she was even curious—Sam O’Ballivan was nothing to her, after all—and she swished her skirts a little as she swept up the walk toward Undine.

“Did you send off for those spring dresses I wanted?” Undine asked, addressing Maddie in an overbright, over-earnest tone, eyes sneaking past her to devour Sam. “If I can’t get Mungo to take me to San Francisco for the worst of it, they’ll be the only gaiety in the whole winter.”

Winters in that part of the Arizona Territory were mild; snow was rare and the temperatures seldom called for cloak or coat. Maddie didn’t bother to point that out, since Undine knew it well enough. “I wired the order to Chicago this afternoon,” she said, accidentally brushing against Mungo as the two of them passed on the porch steps. She paused to watch as her recalcitrant host strode toward Sam and the horses.

“That’s fine,” Undine replied, but she sounded distracted, and when Maddie looked at her, she saw that she was still fastened on Sam. Mungo might as well have been invisible.

“Are the boys home?” Maddie asked, referring to Garrett, Landry and Rex. Ben was visible in the doorway, holding a pup in both arms and taking in the scene in shy silence.

Undine gave a tinkling little laugh. “Why, Maddie Chancelor, have you gone and set your cap for one of my stepsons? Here you are, in the company of the handsomest man in the whole territory, and you’re wondering about those ruffians?”

Maddie smiled, even though her stomach rolled at the thought of “setting her cap” for the likes of the Donaghers. She’d sooner die an old maid or even throw in with Oralee Pringle, than have truck with any of them. Worried that Undine’s last remark might have reached Mungo’s ears, she slipped an arm through the other woman’s and hastily squired her into the front room, with its plank floors, beamed ceiling, and tall stone fireplace.