Полная версия

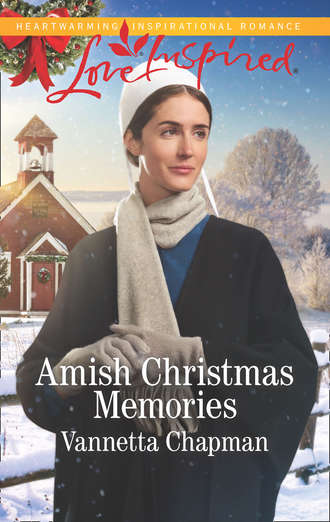

Amish Christmas Memories

Rachel shook her head and spikes of pain brought tears to her eyes.

“I’m not surprised. You have what we call retrograde amnesia caused by a concussion. Often in such a situation, patients have problems remembering events leading up to an accident.”

“I still don’t understand.”

“Retrograde amnesia or a concussion?”

“Both.”

Dr. Gold smiled and patted her hand. “Concussions happen all too often. The brain itself is rather like Jell-O. When a concussion occurs, your brain slides back and forth and bumps up against the walls of your skull. Basically the brain is bruised, and like all bruises it takes time to heal.”

“What would cause such a thing?” Caleb asked. His expression had turned rather fierce. “Does it mean that someone hit her?”

“Not necessarily.” Dr. Gold cocked her head, studying both Ida and Caleb for a few seconds. Then she turned her attention back to Rachel. “You could have been in a car accident, or fallen off a bicycle or simply tripped, and hit your head against the ground.”

“And that would cause a concussion?” Ida asked. “Just falling?”

Caleb sank back into the chair and leaned forward, elbows on his knees, fingers interlaced. “Did it happen when she fell in the snow?”

“Not likely,” Dr. Gold said. “I suspect that Rachel sustained her injury before you ever saw her. It’s why she was meandering back and forth across the road. Concussions often result in vertigo.”

“Can you tell how long it’s been?” Ida asked.

“I can’t. There was no bleeding from the wound, so I rather doubt that someone hit her. More likely it was a simple accident.”

“What about my memory?” Rachel asked. “When will it return?”

“Memories are tricky things. You remembered my name, and you know who these people are. Correct?”

“Caleb.” She met his gaze, remembered again being in his arms. “And Ida, his mamm.”

“Which is a good sign. This tells us your brain is still working the way it should.”

“But I wouldn’t have remembered my name if it hadn’t been written in that book, and I still don’t know where I live or who I am.”

“In most cases those memories will return in time.”

“How much time?”

“Remember what I said earlier? You don’t just have a concussion. You also have retrograde amnesia.”

“And what does that mean?”

“That it may be a few days or weeks or even months before you regain your memories.”

Rachel felt as if she was falling into a long, dark tunnel. She stared down at the cotton blanket covering her and grasped it between both of her hands. “That long?”

“I’m afraid so, but the good news is that your memory is working now, and it will continue to work. You may not be able to remember what happened before the accident, but you can create new memories. Plus you’re healthy in every other way.”

“But what am I to do? Where will I live?”

“If you’d like, we have a social worker here at the hospital that can meet with you and find temporary housing for you. We’ll also put you in contact with a liaison with the Daviess County Sheriff’s Office. Perhaps your family has reported you missing. It could be that they’re looking for you even now.”

“What do I do until they find me?”

“Be patient. Give your brain time to heal. Live your life.”

“I don’t have any money, though.”

“There are charities that provide funds for those in need. You don’t need to worry about money right now.”

“She doesn’t need to worry about where to live, either.” Ida stood and moved to the side of the bed. She was about Rachel’s height but looked a bit shorter, owing to her weight. She wasn’t big exactly, but rounded, like a grandmother should be. She was probably close to fifty with gray and brown strands of hair peeking out from under her prayer kapp. “Rachel, we would be happy to have you stay with us. We have an extra room. It’s only Caleb and John and myself, so it’s a fairly quiet environment. You can rest and heal.”

Rachel didn’t know if that was a good idea. Ida and John seemed like a nice couple, and Caleb had saved her, but she wasn’t sure they wanted a brain-injured person living with them. Then again, what choice did she have?

She didn’t want to go to a police station.

She didn’t want to wait on a social worker.

“Stay with us,” Ida repeated.

“Ya.” Rachel nodded, wiping away the tears that had begun to slide down her cheeks. “Okay. Danki.”

Dr. Gold was pleased with the arrangement, and Ida was grinning as if Christmas had come early, but when Rachel glanced at Caleb, she wasn’t sure if she saw relief or regret in his eyes.

Chapter Two

They returned to Ida and John’s house. The snow had stopped, but it sat in heaps on the side of the road. The clouds had cleared, the sun was shining and Rachel suspected the snow would melt completely by the next day. The Englisch homes they passed already had Christmas decorations out on the lawn. Rachel wasn’t sure what Amish homes did to celebrate for the season. She wasn’t sure what her family had done in the past.

The rest of the day passed in a blur.

She met with the local bishop, Amos Hilty, a kind, elderly man as round as he was tall with tufts of white hair that reminded her of a cotton ball.

She learned that the local community was a blend of Swiss Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch Amish, but she couldn’t tell them which she had been. From the style and color of her dress, they guessed that she came from one of the more progressive districts. Amos assured her that he’d contact the local districts to see if anyone had reported a young woman missing.

“We’ll find your family, Rachel. Try not to worry. Trust that Gotte has a plan and a purpose for your life.”

She wasn’t sure how Gotte could use her accident, her loss of memory, for His good, but she smiled and thanked the bishop for helping her.

Several times that afternoon she had to excuse herself and lie down because of the vertigo and nausea, and bone-deep exhaustion. Ida’s cooking smelled wonderful—it was a meat loaf she’d thrown together and served with mashed potatoes, canned squash, gravy and fresh bread. Rachel thought she could eat three plates, but when she’d taken her first bite, the nausea had returned, and she’d fled to the bathroom.

Now it was ten thirty in the evening and everyone was asleep, but she was starving. Pulling on the robe Ida had loaned her, she padded down the hall to the kitchen. She pulled a pitcher of milk from the icebox and found a tin of cookies when Caleb walked in.

“If you’d eaten your dinner, you wouldn’t be so hungry late at night.” When she didn’t answer and just stood there frozen, as if she’d been caught stealing, he’d walked closer, bumped his shoulder against hers and said, “I’m kidding. Pour me a glass?”

So she did, and they sat down at the table together. She could just make out his outline from the light of the full moon slanting through the window. Oddly, the darkness comforted her, knowing he couldn’t see her well, either. She felt less exposed, less vulnerable.

“I can’t remember if I thanked you...for finding me in the snow. For bringing me here.”

“You didn’t.”

“Danki.”

“Gem Gschehne.”

The words slipped effortlessly between them and brought her a small measure of comfort. At least she remembered how to be polite. Surely that was something.

“You owe me, you know.”

Her head snapped up, and she peered at him through the darkness.

“You scared at least a year off my life when I saw you out there.”

“Lucky for me you did.”

“I’m not sure luck had anything to do with it. Gotte was watching over you, for sure and certain.”

“If He was watching over me, why did this happen? Why can’t I remember anything? What am I supposed to do next?”

“I’m not going to pretend I have the answers to any of those questions.”

“Might be a good time to lie to me and say you do.”

Caleb’s laugh was soft and low and genuine. “We both would regret that later.”

“I suppose.” She sipped the cold milk. At least her stomach didn’t reject it. Maybe she would feel better if she could keep some food down. She hesitantly reached for an oatmeal cranberry cookie.

“Your mamm’s a gut cook.”

“Ya, she is.”

“So it’s just you? You’re an only child?”

“Ya, though my mamm wanted to have more children.”

“Why didn’t she?”

“Something went wrong when she had me, and the doctors said she wouldn’t be able to conceive again.”

“Gotte’s wille.”

“She always wanted a girl, too, so I suppose you’re an answer to that prayer, even if you’re a temporary answer.”

“When you marry, she’ll have a daughter-in-law.”

“So they keep reminding me.” He laughed again, but there was something sad and bitter at the same time in it. His next words had a serious, let’s-get-down-to-business tone. “How are you feeling? I know you keep telling my parents that you’re fine, but it’s obvious you aren’t.”

“Lost. Confused. Sick to my stomach.”

“Food should help settle your stomach.”

She bit into the cookie, which was delicious but could use a little nutmeg. “I just remembered something.”

“You did?”

“Cookies need nutmeg.”

Caleb reached for another. “It’s a beginning.”

“Not much of one.”

“The doctor told you this could take a while.”

“I know...but can you imagine what it’s like for me? I don’t know who I am.”

“You know your name is Rachel.”

“Only because you found my book.”

“Not many Amish girls read Robert Frost. That narrows the prospective field of candidates down a little.”

“Perhaps we could advertise somewhere...”

“The Budget.” Caleb nodded and ran a thumb under his suspenders. “Actually that’s not a bad idea. If you write something up in the morning—”

“What would I write? I don’t remember anything.”

“Okay. Gut point, but perhaps your family will post there. We’ll watch the paper closely.”

“Danki.”

“Gem Gschehne.”

And there it was again—an odd familiarity that bound them together.

“Are you always this nice?”

“Nein. I’m on my best behavior with you because you’ve had a brain injury.”

“Oh, is that so?”

“My normal personality is bullheaded and old-fashioned, which are both apparently bad things. And that’s a direct quote.”

“From?”

“My last girlfriend.”

“Oh. Well, I can’t remember my last boyfriend, so you’re still a step ahead of me.”

Caleb cleared his throat, returned the pitcher of milk to the refrigerator and then sat down across from her again. When he clasped his hands together, she knew she wasn’t going to like what he was about to say. She suddenly felt defensive and bristly, like a cat rubbed the wrong way.

“My parents wanted to give you a few days to adjust, but I think there are some things you should know.”

“There are?”

“Our community is quite conservative—we’re a branch of the Swiss Amish, as Bishop Amos explained.”

“He’s a nice man.”

“As long as you’re staying...well, this is awkward, but...”

“Just spit it out, Caleb.” She’d had this sort of conversation before, though she couldn’t remember the details. Somewhere in her injured brain was the memory of someone else trying to set her straight. Why did people always think they knew what was best for her?

“Our women always keep their heads covered—always.”

“Oh.” Rachel’s hand went to her hair, which was unbraided and not covered. “Even in the house?”

Caleb glanced at her and then away. Finally, he shrugged and said, “Depends, but my point is that for some reason you weren’t wearing a kapp when I found you.”

“Maybe I lost it.”

“And your hair was down—you know, unbraided, like it is now.”

She pulled her hair over her right shoulder, nervously running her fingers through it. “Anything else?”

“Your clothes are all wrong.”

“Excuse me?”

“Wrong color, wrong...pattern or whatever you call it.”

“The color is wrong?”

“We only wear muted colors—no bright greens or blues.”

“Because?”

“Because it draws attention and we’re called to a life of humility and selflessness.”

Rachel jumped up, walked to the sink and rinsed out her cup. When she had her temper under control, or thought she did, she turned back to him. “Any other words of wisdom?”

Caleb was now standing, too, but near the table with his arms crossed in front, as if he was afraid she’d come too close. “Not that I know of...not now...”

“But?”

“Look, Rachel. I’m not being rude or mean. These are things I think you’d be better hearing from me than having people say behind your back.”

“Is that what type of community you have? One that talks behind people’s backs?”

“Every community does that, and it’s more from curiosity and boredom than meanness.”

“All right, then, tell me. What else do I need to know? So I won’t incite gossip and all.”

“It’s only that you’re obviously from a more progressive district.”

“Oh, it’s obvious, is it?”

“And so you might want to question your first instinct for things, stop and watch what other people do, be sensitive to offending others.”

“You are kidding me. That’s what you’re worried about?”

“I’m worried about a lot of things.”

“I’ve lost my entire world, everyone I knew, and you’re concerned I’ll offend someone?”

“I’ve hurt your feelings, and I didn’t mean to do that.”

“That’s something, I suppose.”

“But you’ll thank me tomorrow or the next day or a week from now.”

“I’m not so sure about that, Caleb, but there is one thing I do know.” She stepped closer and looked down at her hair, which was still pulled forward and reached well past her waist. When she glanced back up at him, she saw that he was staring at it. She waited for him to raise his eyes to hers.

He swallowed and shifted from one foot to the other. “There was one thing you wanted to say?”

“Ya. Your old girlfriend?”

“Emily?”

“The one who told you that you were stubborn and old-fashioned.”

“That would be Emily.” He reached up and rubbed at the back of his neck. When he did, she smelled the soap he’d used earlier, noticed the muscles in his arm flex. His blond hair flopped forward, and it occurred to her that he was a nice-looking guy—nice-looking but with a terrible attitude and zero people skills.

“Between you and me—she was right. You are stubborn. You are old-fashioned, and you should keep your helpful hints to yourself.”

And with that, she turned and fled down the hall, feeling better than she had since Caleb had rescued her from the snow.

* * *

The next morning, Caleb took as long with his chores as he dared. There was really no point in avoiding Rachel. She lived in their house now, and he would have to get used to her being around.

His mind darted back to her long hair. It wasn’t brown exactly, or chestnut—more the warm color of honey. It had reminded him of kitten fur. As she’d stood next to him in the kitchen, he’d had the irrational urge to reach out and comb his fingers through it. The moonlight had softened her expression, and for a moment the look of vulnerability had vanished. Sure, it had vanished and been replaced with anger.

He remembered her parting words and almost laughed. He’d only been trying to help, but he’d never been particularly tactful. The fact that she’d called him on it...well, it showed that she had spunk and hopefully that she was healing. He decided to take it for a good sign rather than be offended.

When he walked into the kitchen, he noticed that her hair was properly braided, and she’d apparently borrowed one of his mother’s kapps. Unfortunately, she wore the same dress as the day before. She gave him a pointed look, as if daring him to say something about it, but what could he say? It really wasn’t his business. He’d done his duty by warning her. The rest was out of his hands.

Everyone sat at the table, waiting on him, so he washed his hands quickly and joined them. After a silent prayer, he began to fill his plate. He heaped on portions of scrambled eggs, sizzling sausage, homemade biscuits and breakfast potatoes, which were chopped and fried with onions and bell pepper.

“Someone’s hungry this morning,” Ida said.

“Ya. Mucking out stalls can do that to a man.” He noticed that Rachel was eating, and she looked rested. “How are you feeling this morning, Rachel?”

“Better. Thank you, Caleb.” Her tone was rather formal, and the look she gave him could freeze birds to a tree branch.

He nodded and focused on his plate of food. When he was nearly finished, he began to discuss the day’s work with his father. They had a small enough farm—only seventy acres—but there was always work to do.

“Guess I’ll finish mending that fence this morning.”

“Ya, gut idea.”

His mother jumped up and fetched the coffeepot from the stove burner. She refilled everyone’s mugs, starting with Rachel’s. Usually his mother threw in her opinion on their work, but she’d been deep in conversation with Rachel the entire meal. They’d been thick as thieves talking about who knew what—girl stuff, he supposed.

“Have you thought any more about the alpacas?” Caleb asked.

His father added creamer to his coffee. “I’m a little hesitant, to tell you the truth. I know nothing about the animals.”

“They’re a good investment,” Caleb insisted. “Mr. Vann has decided he’s too old to manage such a big farm.”

Ida looked up in surprise. “It’s hardly bigger than ours, and Mr. Vann is only—”

“Nearly seventy.”

“Not so old, then.” His father shared a smile with his mom. Must have been an old-people’s joke, though his parents were only forty-eight.

“He has no children close enough to help on a daily basis,” Caleb explained. “He’s gifting the farm to his children and grandchildren, who will only use it for a weekend place. Obviously they can’t keep the alpacas.”

“I’m wondering if it’s the best time of year to get into a new business.”

“Better than planting season or harvesting, and he’s letting them go cheap. I’m telling you, if we don’t get them today, they’ll probably be gone.”

“Even a bargain costs money,” John said.

“Ya, I’m aware of that, but we have plenty put back.”

“What good are they, Caleb?” His mother held up a hand. “I’m not arguing with you. It’s only that I know nothing about them.”

“The yarn is quite popular,” Rachel said.

Everyone turned to stare at her. She blushed the color of a pretty rose and added, “I don’t know how I knew that.”

“Did you maybe have alpacas before? At your parents’ farm?”

“I don’t—I don’t think so, but I can remember the yarn. Spinners and knitters and even weavers use it.”

“Any chance you recall how much trouble they are to raise?” His father laughed at his own joke, and then he reached across the table and patted her hand. “I don’t expect you to answer that. I was only teasing because my son seems set on bringing strange animals onto our farm.”

“I thought you were a traditionalist,” Rachel said, then immediately pressed her fingers to her lips as if she wanted to pull back the words.

But if Caleb was worried he might have to answer that, might have to explain in front of his parents their conversation the night before, he was pleasantly mistaken.

Ida was up and clearing dishes, and she answered for him. “Oh, ya. In nearly every way that’s true. Caleb is quite traditional.”

“Unless it comes to animals,” his father said. “We’ve tried camels.”

“How was I to know they’d be so hard to milk?”

“And goats.”

“We learned a lot that time.”

“Ya, we learned if water can go through a fence, then so can a goat.”

“We’re a little off topic here.” Caleb tried to ignore the fact that Rachel was now grinning at him as if she’d discovered the most amusing thing that she might insult him with later. “Let’s just go look at the alpacas together. We could go this morning, and I’ll fix the fence this afternoon.”

“How about we do it the other way around?”

“Deal.”

He was up and out of his chair, already glancing at the clock. If he worked quickly, they could be there before noon—surely before anyone else came along and bought the alpacas out from under their noses.

“Caleb, would you mind making sure that the front porch and steps are free of ice?”

“The front porch?”

“We’re going to have visitors, and I don’t want anyone slipping.”

Visitors? On a Tuesday morning? “I was headed out to work on the fence line.”

“And then look at alpacas. I heard.”

He tugged on his ear. His mother was acting so strangely. Since when did she have weekday visitors? When had she ever asked him to clean off the front-porch steps?

“Shouldn’t take but a few minutes,” his father said. “Your mother wouldn’t ask if she didn’t need it.”

The rebuke was mild, but still he felt his cheeks flushing.

“Ya, of course. Anything else?”

“You could move your muddy boots off the front porch, as well as that sanding project you’ve never finished.”

“Did I miss something? Are we having Sunday service here on a Tuesday?” He meant it as a joke, but it came out as a whine.

Rachel jumped up to help his mother, not even attempting to hide her smile.

“Some ladies are stopping by.” His mother reached up and patted his shoulder. “I just don’t want them tripping over your things.”

He rolled his eyes but assured her that he’d take care of it right away.

When he stepped out onto the front porch, his dad clapped him on the back. “Give them a little space. Your mamm, she’s happy to have another girl around the place.”

“Ya, that makes sense, but—”

“She’s convinced that Gotte brought Rachel into our lives for a reason.”

“To give me more work?”

“And, of course, we all want to make the transition easier for Rachel. This is bound to be a difficult time.”

From the grin on Rachel’s face, he didn’t think it was as difficult as his father imagined, but instead of arguing with him, he found the stiff outdoor broom and began sweeping the steps to make sure there was no ice or water or snow there. Woman’s work, he thought, but that wasn’t what was bothering him. Change was in the air, and Caleb had never been one to embrace change—unless it was regarding farm animals.

In every other way, stubborn and old-fashioned was more his style.

* * *

Ida had shared with Rachel that a few ladies would be stopping by. “They heard about your situation and want to help.”

She wasn’t sure what that meant, but she’d nodded politely, and then Caleb had brought up alpacas, and the conversation had twisted and turned from there.

Now it was nearly noon, and she plopped onto the couch and stared at the items stacked on the coffee table.

Ida sat across from her, holding a steaming mug of coffee. “Seems everyone from our community pitched in. It’s gut, ya?”

“Of course. I’m a bit stunned. How did they even know that I’d need these things? How did they know I was here?”

“Word travels fast in an Amish community. Certainly you remember that.”

“We used to call it the Amish grapevine.”

Ida laughed. “I’ve heard that before, too, but ‘grapevine’ has a gossipy sound to it. This is really just neighbors helping neighbors.”

Rachel picked the top dress off the pile of clothes. The color was midnight blue—Caleb would be happy about that—and the fabric was a good cotton that would last. It was also soft to the touch. She ran her hand across it, humbled by all that these women, who were strangers to her, had given.