Полная версия

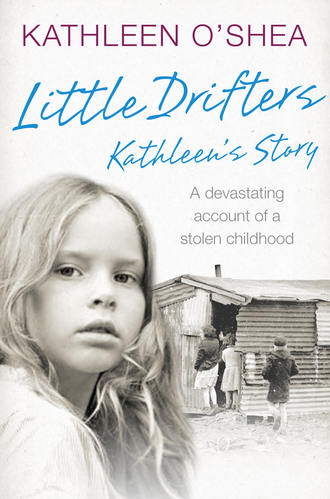

Little Drifters: Kathleen’s Story

I nodded, pretending I knew what she meant, but really I had no idea what a mental hospital was. Later Brian explained: ‘It’s a place to fix Daddy’s head so he thinks better.’

We all agreed that this was a very good idea because Daddy wasn’t thinking too well at the moment. The only problem was that, with both our parents gone, we were left to fend for ourselves. It was Claire and Bridget who took on the responsibility of caring for us children: dressing, feeding and washing us every day.

There were days we had so little to eat they’d put us all in the cart while we travelled from one farmer to the next to beg some food. Luckily, all the farmers were kind and they’d give us eggs, milk and vegetables so we managed to get by until Mammy returned a few weeks later. We were so happy to see her and suddenly felt a lot safer.

A week after that, Daddy came back too. He was more composed and calmer than before and he’d sworn off the drink, which we all thought was for the best.

‘Daddy, what was the mental hospital like?’ Brian asked that evening.

‘Ah, it wasn’t all that nice,’ Daddy said, a little sadly, as he stroked Floss, who probably missed my father the most when he was gone. ‘They give me the electric shocks to get my head straight again.’

‘What’s that, then? Electric shocks?’ Brian was in a curious mood.

‘It’s like being struck by lightning,’ Daddy explained. ‘Like a big bolt of lightning in your head.’

We all gasped in horror – imagine being struck by lightning to make you better! It sounded horrifying. But at least we had our parents back again.

Weeks later my parents announced they had to go into town to get a bit of shopping and they’d be back later in the day. We were desperate to go with them, but no amount of begging and pleading from any of us would change their minds.

‘We have something important to do. We won’t be long,’ my mother said as she pulled on her heavy winter coat and they both started walking down the road.

So we spent the day roaming the fields and climbing trees as usual. On our way home we spotted Mammy and Daddy walking back towards the wagon just ahead of us so we all ran and surrounded them, happy to see them back. My mother was carrying a bundle of blankets in her arms.

Brian asked my mother: ‘What’s that you’re carrying in your arms? In that blanket?’

‘Ah, I got a little sister for you lot. Her name is Libby,’ my mother replied as she gently bent down to show off the baby.

‘Wow, a baby! Where did you get the baby?’ I asked excitedly. We loved babies and we all tried to clamber over my mother to catch a glimpse.

‘Well, we were walking past this farmer’s field and there were cabbages growing there. Mammy saw a leg sticking out and Mammy pulled out this little baby!’ She laughed as she grabbed my hand. We all walked back together, our attention focused on the new addition to the family – a new sister, Libby!

Brian, Tara, Colin and I were out and about the next day with nothing particular planned when Brian had an idea.

‘I want to get myself a baby like our mother did!’ he said. ‘Didn’t she say she got it from under the cabbages? There must be a cabbage field somewhere and we’ll get our own babies to look after. That’s what we’ll do. We could get a few babies each. Now what do you lot think about that? Ain’t that a grand idea!’

Brian beamed. He was always so clever and smart, always the one thinking up the new schemes and games. And this one seemed like a really good idea, one of his best!

So we crossed the fields, skipping along, our strides quickening until we got to the farm. There we saw all the cabbages with the white heads peeking out of the soil.

There were rows and rows of cabbages, hundreds, thousands of them! Where to start? We were already bursting with excitement at the prospect of having all those babies.

Brian went first. He stepped up to the cabbage nearest to him while we stood watching, full of anticipation. He bent down to grab it and started pulling it out of the ground. It wasn’t that easy. He yanked it, left and right, loosening up the soil before giving it one mighty heave and, with a sudden jerk, the cabbage came loose and he stumbled backwards. He threw it to the side then went to investigate the hole that it had left behind. We all peered in beside him, eager to see the baby – but there wasn’t one! We were shocked.

‘I don’t understand.’ Brian was baffled. ‘Mammy said she’d found it under the cabbage.’

Tara chimed in: ‘Maybe there ain’t one under that one, but there could be one under this cabbage.’ And she headed over to another cabbage to start work.

Then we all started pulling up the cabbages, all of us criss-crossing each other as we pulled out the vegetables, then cursing at our luck as we glared into empty holes. We pulled out one after another after another, but there were no babies. Not a single one.

We were all confused and bitterly disappointed.

‘I can’t find one, Brian,’ I spoke out. ‘Maybe there is no baby here or it might be somewhere else. Maybe you have to find a special one or a magic one.’

‘Yes, Brian. I’m tired. Maybe we should go and do something else,’ Tara added while Colin sat on the ground poking a stick into the mud, waiting on us to see what we’d do.

‘No! There must be a baby! Mammy said so. Go and pull out a bit more,’ Brian shouted back, angry and frustrated. By now we were all covered in mud – it was in our clothes, our faces and our hair – and so tired of digging that we gave up. The field was a mess with cabbages strewn everywhere and we walked back to the wagon dejected. We were so sure about the babies that our failure was hard to comprehend.

As we walked into the campsite Brian was still going on about finding babies: ‘I’m going back there tomorrow. I’ll find one.’

‘Jesus Christ!’ Suddenly we heard our sister Bridget’s incredulous shout. ‘Look at the lot of you! You’re covered in mud!’

Claire seemed equally horrified as she caught sight of us: ‘Lads, what have you lot been up to? Oh my God, look at how filthy you are! Mammy will go mad seeing you lot like that.’

They both shook their heads as they turned us about, examining us from head to toe. Mud clung to every part of us.

‘Come, let’s get down to the river to get all that filth off you before your parents see you,’ she added.

Bridget grabbed a towel as she quickly ushered us towards the river.

As she was washing us down she asked: ‘Anyway, how did you manage to get this filthy?’

‘We were digging up cabbages in the farmer’s field,’ I answered.

‘You what? You did what?’ Bridget was stunned.

I thought that Bridget didn’t hear me properly so I told her of our day on the field looking for babies as Brian, Tara and Colin nodded along. Claire and Bridget were completely gobsmacked and after I’d finished my story they just looked at each other before bursting out laughing. They were in stitches. They couldn’t believe what we had done.

Finally, when they calmed down enough to talk, Bridget warned us not to go back to the field.

‘The farmer will be going mad after you lot destroyed his crop. There is no baby under the cabbage and there never will be. The baby came out from Mammy. Your Mammy was only playing with you lot when she said about the cabbages.’

‘But Bridget, she did say it,’ I insisted, unconvinced.

‘Look, you lot better not go round saying this but that day when your father kicked your mother he kicked the baby out of her. She was pregnant – us older ones knew but you lot didn’t have a clue. All that blood on the ground, that was from the baby. And she was too early and little and that’s why she had to stay in hospital all the time, to get stronger. Now stay away from the farmer and let that be it.’

We walked back to the wagon in silence. The river water was cold and I shivered as my mind returned to that frightening day that I saw my mother get hurt. I saw the blood stain on the ground. I recalled her haunting cries and the ambulance coming to take her away. I know now how our sister Libby came into this world. Libby was born prematurely, and by the time our parents brought her home she was already four months old.

With the new addition in the family, the wagon felt more cramped than ever. We were forever climbing over one another, and one day, when Tara and I were playing, Tara was clambering round the stove to get to me when, suddenly, she slipped. One second I saw her, and the next she was gone. She’d fallen straight into the middle of the stove’s chimney stack. Her pitiful screams as her body touched the hot chimney were awful. Mammy bolted to grab Tara, who was now in hysterics, her small body scorched and singed from the fire.

I watched on, petrified, as Mammy ripped the smouldering clothes off my sister to reveal the red raw burns on her legs and body and her skin bubbling up into sacks of liquid. Mammy worked quickly, dousing Tara with pails of cold water while my father rushed to get the horse and cart. Everything was chaotic. I was glad to see the horse and cart galloping away with both our parents and Tara, who was still crying her eyes out over the pain. At least I knew she was going to get help but I missed Tara terribly. She was much more than my sister; she was my friend and companion. Of all my siblings, we were the closest, and every day without her felt like an age.

Tara was badly burned on the inside of her thighs and her stomach and she had some smaller burns on her hands. It was a pitiful sight when she finally returned from hospital, struggling to walk because of the pain. She was so miserable that she stayed in bed most of the time. I stayed with her to keep her company and cheer her up as much as I could. She had to go to the clinic a few times to get the bandages re-dressed and it was a week before the pain started to ease and she was able to smile again.

As if things weren’t bad enough, even the weather conspired against us. It was early winter now and the sky looked constantly dirty and gloomy, never-ending clouds blocking out the sun. One day the wind was so strong and blustery we young ones found it hard to get about. Each time we tried to move from one place to another we were pushed off course by the powerful gusts. At first we laughed as it blew us off our feet but then the leaves and debris started to fly about and we got scared. Daddy was worried too and he called for everyone to come outside the wagons as he threw ropes over them to try and pin them down. But the winds were only getting stronger and the wagons started pitching and shaking from side to side.

Now the rain pelted down and every minute it seemed the storm was getting worse.

‘We need to get to a sheltered area,’ Daddy shouted over the deafening gales. ‘These wagons could go over at this rate!’

Aidan and Liam nodded, working quickly to tie the horses up to the wagons to drive them down the roadside. There they waited for all of us to get on. We moved as quickly as we could, the air around us now stirred up and swirling with debris. Every second this storm seemed to be gathering momentum and power. The wind pushed at the trees’ branches so they lashed at us like long arms. We were terrified, each of us jumping up into the wagons for safety. Once we were all aboard Daddy let out a massive ‘Yarhh!’, cracked the reins and galloped the horses hard. We rocked and bounced down the road. I could hear the wagon brushing against the trees as we all held tight, petrified for our lives. Daddy drove us as fast as he dared into the woodlands, hoping that the trees would provide us with a bit of shelter. As we came into the thickest part of the wood we all felt the wind lessen around us.

We stopped, listening, Daddy breathing hard, and just at that moment we heard a tremendous crack, followed by an ear-splitting crash.

The horses reared up, their ears pinned back in alarm, and we all scrambled out of our wagon to see what had happened. There we saw a tree lying right into the middle of the second wagon. We were stunned. I was so fearful that somebody must be hurt inside but then my brothers and sisters popped out of the wagon one by one, completely unharmed. That night we all slept in the one wagon in the middle of the woods while my father kept watch over us.

By morning the storm had moved on and we woke to see the second wagon buried under leaves and branches while the tree trunk rested slanted with its root jutting out at the other end. It had fallen right into the middle part of the wagon, leaving a gaping hole in the ceiling. Luckily, Daddy said it looked worse than it actually was and he quickly set about fixing it up with Aidan and Liam.

Secretly, Tara and I were disappointed. We’d had enough of the wagons now and we’d hoped the storm might signal an end to our hard life on the road. But Daddy wasn’t giving up, even when the weather turned bitterly cold and snow started to come down in thick white clumps. That first winter was so cold that, even huddled together under a blanket, we shivered while we slept. Yes, life aboard the wagons was certainly harder than we’d imagined. I was quietly yearning to be back in a proper house. By summer we could play out and enjoy ourselves again, but as the second winter approached I felt a horrible dread rising up in me. Things were tough but I had no idea of the terrors another winter would bring.

Chapter 4

A Birth and a Death

We knew the snow was coming long before it arrived. It was exceptionally cold that year. Daddy said it over and over. He could always tell what the weather was going to do and he’d been looking up in the sky for days now, tutting and shaking his head: ‘There’s snow coming. Big snow.’

Of course, all us kids were excited – we loved playing in the snow. But none of us could have imagined how hard and heavy it would come down that year. Once those large flakes started drifting to the ground, it didn’t stop. For days it snowed and snowed until afterwards the fields, roads and everything else as far as your eyes could see was buried deep under a white carpet, truly transforming the landscape. It was just as well that we knew our surroundings like the backs of our hands or we could have got lost just by walking out of the campsite.

Now the deep snow made life a lot harder for us to move around, and our daily chores of fetching water and collecting wood became almost impossible.

Still, we always tried to have fun and often we’d start off on a chore before ending up in the middle of a snowball fight, ducking, diving and laughing as the snowballs found their marks. We built huge tunnels in the snow and massive snowballs which we’d push down the hills, watching in fascination as they grew bigger with every turn.

It was always great fun until our hands froze and then we’d have to go back inside the wagon, crying from the pain.

‘Mammy, our hands hurt. It hurts, do something, Mammy!’ Tara and I cried out as soon as we saw her.

‘There, didn’t I tell you lot not to overdo it playing in the snow,’ Mammy chided, placing our hands in a basin of warm water and gently massaging them to relieve the pain and the numbness. Of course, it wasn’t long before we’d get the feeling in our fingers back and we’d be at the snow again. There really wasn’t much else to do as we were stranded about a mile from the village.

One night I woke up with the cold, despite the warm blanket and the body heat from Tara, who lay curled behind my back, her breathing deep and relaxed. My mother was asleep on the bunk below us with my brother Colin and Libby. I climbed carefully down the small ladder and reached for the box under the bunk, where my mother kept the socks. I could hear the wind howling outside and the wagon swayed when a gust of wind whistled past. It sounded so wild and scary that I hurried to pick up two pairs of my father’s socks, rolling them as far up my legs as I could before creeping back up the ladder to my bunk and huddling up to Tara. I was slowly regaining a bit of warmth and was almost asleep when I heard my mother groaning beneath me.

Instinctively, I leaned my head over the bed to look down.

My mother was sitting up panting, gripping the pole of the bunk so tightly her knuckles were white while her other hand held her belly. Her face was misshapen as she grimaced, gritting her teeth with pain.

Sweat dripped from her brow and her eyes were shut tight in intense concentration.

‘Mammy, you look sick,’ I said as I came down the ladder, scared at what was happening to my mother.

‘Go and get Claire and Bridget!’ she spoke between rapid breaths.

I didn’t need to be told twice. I threw on my coat and Wellingtons, jumped down off the wagon into fresh snow and ran across to the other wagon. Thick snowflakes rained down heavily, and the cross-wind was so cold and fierce that my cheeks were already stinging by the time I got to the door.

As soon as I opened it up, I shouted for Claire and Bridget. Groggily, Bridget sat up in the bed: ‘Are you gone in the head, Kathleen?’

The breeze blew in behind me and the others sat up in their beds.

‘You gobshite! Shut the feckin’ door! It’s freezing!’ Liam shouted from the top bunk. Breathing heavily, I managed to tell them that Mammy was in pain and she needed them to come quickly.

The fear in my voice must have convinced them of the urgency for they all jumped out of their beds and grabbed their clothes in a flash. Bridget rushed to my mother while Claire took charge of the rest of us, ushering us into the second wagon. Aidan and Liam were instructed to go to the village to get our father from the pub and also a midwife as my mother was about to have a baby! My brothers had to trek a mile across deep, snowy fields in a blizzard to fetch help. Meanwhile, my mother’s groaning turned to screams. We were all shaken by the terrifying sounds coming from the other wagon. Claire’s face was almost frozen in fear.

‘You lot stay in the wagon now,’ she told us. ‘I have to check on Mammy.’

She ran outside into the snowstorm as the screams came louder now – then suddenly the screaming stopped. We all waited anxiously, not knowing what was going on, holding each other for comfort and warmth. None of us spoke. Finally, we were relieved to hear the voices of our brothers and father accompanied by another voice which we reckoned must have been the midwife. Soon after, Claire clambered back in the wagon.

‘Mammy is all right and she is being attended to by the midwife,’ she said, smiling reassuringly.

‘Bridget and our father are with her. She has given birth to a baby girl. We knew she was going to have another one but no one thought she would come so quick. She had her before the midwife even arrived. We had to wrap the poor little thing up in newspapers to keep her warm, but the baby’s fine. There’s nothing more to do but to wait till the ambulance gets here. Lie down and try to get some sleep.’

Claire spoke calmly, and as her words registered in my mind all the tension and stress of the past few hours left me. I had been so scared for my mother. Everyone sighed with relief that all was well.

In fact, it would take hours for the ambulance to arrive as the snowstorm had made our road impassable. A snow-plough was brought in first before the ambulance could come through and take my mother and the new baby to the hospital. And that is how our baby sister Lucy arrived in the world.

Mammy and the baby returned a few days later, along with the Legion of Mary workers who had now been alerted to our plight out in the middle of the fields, cut off from the village by the snow. They brought winter jackets, Wellington boots and blankets to fend off the worst of the cold and gave Mammy food vouchers to help feed all of us children. We were all grateful for the extra warmth and food. But in truth I never truly relaxed until I woke up one morning, well over a month after the drifts cut us off, to see the first thaw and the green and brown fields re-emerging from under their winter blankets.

‘Have you seen Floss anywhere this morning?’

Daddy was up and about early that spring morning, tending to his horses as usual, bringing in the hay, grooming their coats and changing their shoes. But now he was searching the campsite, a concerned look on his face.

‘It’s probably nothing but it’s a bit strange that he’s not about,’ he added, absent-mindedly. ‘Have you seen him?’

I was not long woken up and still had a bleary head, full of sleep.

‘No,’ I replied. ‘I’ve only just got out the wagon, Daddy.’

I was keen to help so I got Tara up and we set about looking for Daddy’s favourite dog. We didn’t have to walk far, just about 50 yards from the wagon, when we came across Floss lying under a tree.

Thinking he was asleep, I started calling out: ‘Hey, Floss! Come here, boy.’

We waited a while but Floss didn’t move a muscle.

‘God! That Floss must be asleep,’ I said to Tara and we crouched next to Floss as I said again: ‘Come on, get up, you lazy dog!’

I went to give Floss a shove, but when I touched him his body was stiff. I tried to heave him to one side but Floss just flopped back, lifeless.

‘Oh my God, Tara. Floss has died. He ain’t moving.’

We both started to cry – Floss wasn’t just like a dog, He was one of our family. We ran back screaming: ‘Daddy! Daddy, we found Floss but he’s dead. We found him under that tree over there.’

I pointed in the direction of the tree.

‘You what …?’ My father didn’t get out two words before he ran to the tree and threw himself down on the ground where Floss lay.

I heard him shouting out: ‘No. No. No!’

Tara and I followed behind and came upon my father, utterly distraught. Daddy was sobbing his heart out at the death of his friend and companion. I couldn’t help but cry seeing my father in so much despair, and so did Tara. As my father’s cries could be heard all round the campsite, gradually the others came to see and each of us shed tears at the loss of our dear Floss.

Daddy was inconsolable. He lay down next to Floss and stayed there, by his side, crying and talking to him. The day went on. We got ourselves some food but Daddy wouldn’t move. As day shifted into night Tara and I came to sit with our father.

‘See that dog Floss,’ he said to us, now taking long swigs from a bottle of Guinness. ‘We’ve been everywhere together. That’s the smartest dog you’ll ever find. You know, I sold that dog to a lot of the farmers and got quite a bit of money for him but the dog never stayed. He always found his way back home.’

Daddy laughed with the memory but then his sadness consumed him and he started crying again. Daddy didn’t come in the wagon that night – no matter how much my mother coaxed him he refused to leave Floss’s side. For three days Daddy slept outdoors next to his dog until eventually Mammy managed to persuade him to bury the remains, which were now beginning to decay and smell.

A little bit of Daddy died with Floss. You could see that his heartache weighed heavy on him for a long while. I hadn’t seen him like this before, even after the time a man came to get Daddy to tell him his mammy was dying from TB. Daddy had gone back to his home town, and though he was still banned from his parents’ home he saw my grandmother in hospital. He told us she had died in his arms and for a while he was sad and quiet. Daddy was always devoted to his mother and she adored him too. But when Floss died, Daddy was a wreck. Eventually he pulled himself together. The horse fair was coming up and he had to prepare all his horses, making sure they were in top nick. Eventually, Daddy left for the fair with Liam and Aidan. They returned two days later, pleased with their trades. They’d managed to sell off the horses and buy a good-looking chestnut mare.

She was lively and energetic, though she could be snappy and headstrong. My father seemed contented with the sale but he was still tortured over the loss of his dear Floss. Now he spent a lot of his time and money in the pub, drunk in the company of his friends. Mammy was left in charge of us all with no money and nothing to feed us, and this started a lot of arguments between them.