Полная версия

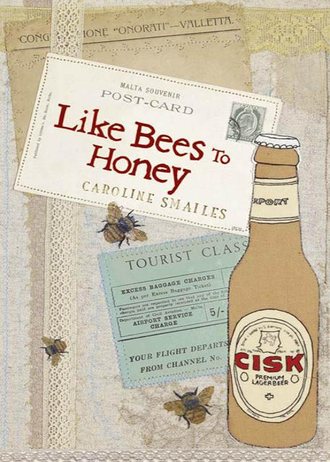

Like Bees to Honey

I cannot explain where it has gone; only that it no longer keeps those in, those out.

I walk into my mother’s house, dragging my suitcase over debris. My eyes begin to adjust. I see through the dust and the rubble and the rubbish. The smell hits me, decaying, riddled.

I stop. I begin to hold my breath, to count, in Maltese.

I close my eyes.

Wie

~one, two, three, four, five.

I open my eyes.

My eyes transform the tumbled ceilings, the broken banisters and within moments I am standing in my mother’s hallway. A grand sweeping staircase is on my right. A wooden coat stand, garnished with elaborate carvings, is to my left. I take off my shawl. I drape it onto the stand, next to my mother’s lace shawl. I release the grip of my suitcase, resting it near to the wall.

I shiver. It is cold in Malta. I feel cold in my bones, shiver shiver, shiver shiver.

And then, my mother walks in from the kitchen.

She is ahead of me, rubbing her hands over her hair, shaping her black backcombed locks into a ball. She looks young, fresh, alive. She looks my age, mid thirties, I see my shape in her curved figure. Her lips are covered in red lipstick; she is wearing her house clothes, covered with an apron. She has been cooking, I smell, I am hungry.

‘Nina, qalbi!

~Nina, my heart! You came back home for me.

She holds out her arms, wide, and as I move towards her I become enveloped in her scent.

‘Jien qieg

~I am home.

The embrace is broken.

‘Christopher, where is he?’ I ask.

My eyes search, I panic.

‘He will be with Geordie, Aunt Elena’s Englishman, don’t worry. Ikunu qed jaqsmu l-birra ma’

~they will be sharing beer with Jesus.

My mother is smiling.

‘Cic

‘He does, you’ll meet him.’

My mother says.

‘Why are there so many dead people here?’ I ask.

‘All troubled souls come to Malta, qalbi.’

~my heart.

‘But why, Mama?’ I ask.

‘You don’t remember, qalbi? To heal, the good come here to heal.’

My mother says.

We are in the kitchen.

My mother stands near to her cooker; two plates, a bowl, two forks and a large silver spoon are laid out, ready. I lean my bottom onto one of the wooden chairs; there are six surrounding the kitchen table. In the centre of the table, a glistening crystal bowl contains one single orange.

‘Cic

She says, spooning out aran

~baked rice balls filled with cheese, meat sauce, peas, rice. The outside is covered in breadcrumbs.

I watch my mother.

I look as the perfect rice balls are transferred from bowl, to spoon, to plate, with ease. It was my favourite dish as a child, my mother has remembered, she has cooked them to welcome, without words. Her rice balls are filled with mozzarella, the taste used to linger, melt. The taste was unique to my mother’s recipe, different, special.

I smile.

I cross my arms over my chest, my hands rubbing to warm the tops of my arms. My mouth is filled with anticipation, juices.

‘Are you cold, qalbi?’

~my heart.

‘I am cold in my bones,’ I say.

‘You will find warmth, come, eat.’

She hands me a plate and a fork, the aran

I think to how Christopher and I would attempt to replicate, to make aran

I shiver.

I think of Molly. I have never cooked with Molly. Her daddy has, I cannot.

I shiver.

My mother sits next to me.

‘You cooked my favourite, thank you.’

I want to talk, to spill, to tell my mother all in the hope that she will help me, that she will make me better. I cannot find the words, not yet. My mother reads my thoughts.

‘Listen. Eat, relax and then we will talk, but not of our past, qalbi. You came home, I forgive you, qalbi.’

~my heart.

She says and then brushes her cold hand over mine.

I eat.

And when I have finished my mother peels me the last of the oranges that have fallen from a neighbour’s garden, into her backyard.

‘Listen, I have had too many this year, that neighbour should trim his tree. You remember that I hate waste, qalbi.’

~my heart.

She tells me.

‘But you like oranges so,’ I say.

‘There are many wasted this year. They have been rotting on my floor. Listen, there are too many spiders in the backyard and you know that I have such fear of creepy crawlies, qalbi.’

~my heart.

She tells me.

I think to my mother and remember her screams each time a spider, a cockroach, any insect and sometimes a simple house fly would enter into our home. My mother’s screams would be heard all the way down the slope and from boats within the harbour. I lift the orange segments, smiling.

The orange taste tangs, bitter sweet. I lift my fingers to my nose, I inhale. My fingers are covered in the smell of home.

‘G

~you have the fingers of a pianist.

My mother says and then laughs, ha ha ha.

‘I never had the patience to learn, my feet liked to patter too much,’ I say.

There is a silence, slightly too long.

‘Go into the parlour, qalbi, you look so tired, rest in my chair, use my blanket.’

~my heart.

She speaks softly, clearing the dishes from the table, placing them into the plastic bowl in her sink. My mother has her back to me.

‘Your bedroom is the same as when you left. You will feel safe in there, qalbi. It will help you to remember.’

~my heart.

I move into the parlour, I curl onto the chair.

I turn my knees, my body, so that I fit. I drift into sleep in my mother’s chair, with my mother’s crocheted blanket wrapped around me, warming my cold bones, but still I shiver shiver, shiver shiver.

Matt,

I dreamed of you last night.

I was sitting on the steps outside of the Rotunda of St Marija Assunta. The midday sun was beating down onto my shaven legs. They were itching; I had nipped the skin around my ankle, the itch was forming a scab. I was beginning to heal. I had hitched up my white cotton dress and enveloped the skirt to under my thighs. I had forgotten my sunglasses. My right hand shielded my eyes from the white glow. I was squinting. I was waiting, for you. I will always wait, for you.

In my dream, I tag on to the flowing skirt of a passer-by. She is Maltese. Her skirt is harsh between my fingertips. In my dream, I open my mouth, poised to ask her the time. But the Maltese words will not flow from me. I have forgotten my words. I have forgotten the words that I was born knowing, that are woven through my lives. In my dream the words escape me. They do not grip to my tongue. ‘Sku.zi. Tista’ tg

I said that I dreamed of you. I did not tell you that you were not present in my dream. Instead, I was covered with a feeling and that feeling has become you. A covering that is longing.

You are the tongue that I long for. I ache with lovesickness,

Nina

Tmienja

~eight

Malta’s top 5: About Malta

* 4. Transport

For those who do not wish to risk hiring a car and driving around Malta, the buses on the island are easily recognised by their bright yellow bodies and orange stripe. They are a cheap and convenient mode of transport, offering a slow but scenic ride. Most journeys begin at the bus terminal in the capital city Valletta.

I have been back in Malta for one day, I think. It feels longer. Already time has little importance, is being blurred, lost.

I am sitting at my mother’s kitchen table. My mother has opened her cupboards and is balancing on her tiptoes, stretching in, moving around tins, jars, pasta, vegetables, flour. She has her back to me. Her dress has risen to the fold in the back of her knee. I look to see the perfectly formed muscles on her stretched calves. She always loved dancing with my father. My mother talks into the wood of the cupboards, ignoring my responses to her food-related questions.

She wants me to eat more, she wants to prepare something additional, extra, indulgent for me, but I am full to my throat. I refuse, over and over. She does not listen.

My fingers are trailing the rim of the empty crystal fruit bowl.

‘L-aqwa li

~you came back home, that is all that matters.

My mother breaks my thoughts.

‘I’m too late,’ I reply.

‘Listen, when you left I told you naqta’ qalbi.’

~I cut my heart, I lost hope.

‘I remember,’ I say.

‘But you came home to Malta and now again I have hope.’

‘I have no hope. I’m lost Mama.’

I sob.

‘No, qalbi, no. There is always hope.’

~my heart.

‘I’m here; I’ve abandoned my husband, my daughter. I don’t know what to do next. Please will you help me?’ I ask.

‘Search the island Nina, find yourself. And then we will talk.’

My mother tells me.

‘Come with me, guide me, please,’ I say.

‘I cannot. I will only leave this home one more time.’

‘I don’t understand,’ I say.

‘You will.’

She speaks the words softly and then moves to me. My mother places her cold hands onto my shoulders and looks into my eyes, then over my face.

I shiver.

‘U qalbi.’

~and my heart.

She says.

‘Inti g

~you are naked without lipstick.

She tells me and then pulls me into her scent.

‘Have you seen your bedroom?’

My mother asks.

‘Not yet,’ I say, into the material of her house clothes.

The wooden banister is smooth under my fingers. My great-grandfather had carved it, a wedding present for my grandfather, my mother’s father. My mother and I would polish it every day. It shone, it gleamed, it was proud and glorious. My fingertips tease the surface as I walk the marble steps of my mother’s grand sweeping staircase.

My bedroom door is open, welcoming; the morning light, my Lord’s smile, shines in through the window’s net covering. I stand in the doorway and my eyes flick around the room, as I hold my breath from fear that I will exhale and puff the image away. It all feels so fragile, delicate, temporary.

Everything is as it had once been. My summer clothes hang in the open wardrobe, all pressed and blemish free. My bookcases are crowded with childhood books, Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl, with bootleg cassettes bought from Valletta’s Sunday morning market, with frilly favours from family weddings and baptisms, with statues of Cinderella, so many statues of Cinderella. I dare not step into my room. Instead, I look at my walls, at the framed photographs of my cousins, my sisters, my grandparents, of me. And then I look at my bed, my Rosary lies across my pillow, a crucifix is nailed to the wall above; a photograph of my parents is framed, is perched on my bedside cabinet, is making my stomach churn.

I step back, I close my bedroom door, I walk down the marble steps and I drag my suitcase from the wall near to the wooden coat stand and into my mother’s parlour.

I am dressing, clothes spilling from my open suitcase and onto the floor, next to my mother’s chair.

I hear banging, glass smashing. I run half-dressed, my white cotton dress unbuttoned, into my mother’s kitchen. I am full of fear.

My mother is at the sink, safe, facing the doorway, water is dripping from her hands and to her sandalled feet.

there appears to be a swirling.

~s – wir.

~s – wir.

whirling see-through ghost swishing around the room. She is grey, rotating the kitchen at top speed.

‘Mama?’ I shriek.

My mother smiles, calm, then raises her eyebrows, a frown.

‘It is just Tilly. She is our resent-filled

~ghost, usually the protector of a house but may become bitter.

My mother says the words in a loud, a stern voice.

‘Mama, why is she here?’ I ask.

‘She is healing.’

My mother says.

Tilly stops spinning, flipping on the spot, instead.

‘You’re a lucky cow.’

She says to me; then she drifts, floats, spins out the kitchen, out through me.

‘Mama?’ My voice is high pitched.

‘It is just Tilly. You will get used to her, qalbi.’

~my heart.

I return to my mother’s parlour, buttoning my dress with trembling fingers.

Today I wear layers, a white cotton dress, a shawl, a cardigan, to unpeel. I am an onion. I discard my knee-length boots. I find flip-flops next to my mother’s chair, perhaps they once belonged to one of my sisters. My mother has told me that it is hot outside, unexpectedly for February; my mother tells me that my Lord is happy.

I frown.

‘Will you move your suitcase to your bedroom, qalbi?’

~my heart.

My mother asks.

‘Maybe later,’ I say, I lie.

Christopher walks in from the kitchen.

‘Will you come with me today?’ I ask my son.

‘No, I can’t. Go find yourself, Mama.’

He tells me.

I know that he has been talking to my mother.

‘But what will you do?’ I ask.

‘I’m meeting Geordie.’

He tells me.

‘Why is he in Malta?’ I ask.

‘He’s waiting, like me.’

He tells me.

‘What will you do today?’ I ask.

‘We will share beer with Jesus, of course.’

Christopher says and then laughs, ha ha ha.

I think, you are too young to be drinking beer. I think, Jesus should know better.

Christopher runs out through the door, laughing and shouting over his shoulder.

‘Mama you worry too much. Age does not matter in my world.’

I smile.

I am leaving my mother’s house.

I open the green front door and stand on the step.

The door closes behind me, I hear a key turning.

and a.

~cl – unk.

as the barrel revolves.

I am forced out onto the cobbles.

I look, the chain and padlock are connected, have reappeared.

I flip, I flop up the slope.

~fl – ip.

~fl – op.

~fl – ip.

~fl – op.

hurrying to catch a yellow Maltese bus.

The sun beats down. I walk in shadows, in shade. I look to the floor and I concentrate on the sounds that flip and flop behind me. My feet offer rhythm. I smile. I focus on my musical feet and alter my flip-flopping to create patterns that are flowing, melodic, light. I offer small leaps; I twirl as I flip, as I flop.

I must look ridiculous, but in this moment I do not care. I feel different, already, today. I do not know if this is good or if this is bad.

I feel lighter. I feel that I could float, or fly, or hover.

I want to fly.

I leave the protection of the city walls and the buildings that lean inwards, that shelter. I walk out through the City Gate. The sun beats down, bubbling my blood. I sweat.

I am at the bus terminal. The pavement is curved with kiosks in varied sizes, in different colours, each selling drinks, snacks, newspapers, cigarettes, magazines, souvenirs. The kiosks mark a line, a curved line, for where the buses will stop, where people must wait, must buy.

I pick up a bottle of water from the smallest blue kiosk. A little girl stands on an overturned plastic crate, behind the counter. The kiosk smells of stale alcohol, the girl is alone. She looks to be the same age as Molly, small, innocent, unaccompanied. I look around for an adult, for her parent.

‘Fejn hu il-

~where is your parent?

The child does not speak. She holds out her palm, with her almost black eyes drilling into my face. I stare at her palm. There are no lines marking the skin, it is smooth, clean.

I fumble, I place a single euro into her hand. The child does not speak, she does not smile, she does not retract her hand, she does not remove her eyes from my face. I turn, I walk. I feel her stare following me as I flip-flop away, to the bus.

I climb the metal steps, one, two, three, of the first bus that I reach.

The white roof, the yellow paint, the orange stripe, they comfort.

As the bus pulls out onto the road, I look to the kiosk. The child has gone. A bearded man wears a pink sun visor. He tips the pink plastic peak to me and then, inside my head, I hear his gravelly laugh, ha ha ha.

The bus is not busy. I am glad.

I rest the side of my head onto the cool window and I move with the bus. We bounce, we swerve, we dip, we jolt. I press my face, harder, onto the glass. It cools me.

I think, I am invisible.

I close my eyes and I breathe the dust, in and out, in and out.

I listen to the quiet prayers that the bus driver mutters.

He is blessing my soul.

I wonder if he is too late.

The creaky bus is fast.

I watch from the window.

The bus takes me through Birkirkara, slowing to a crawl past the house where my grandmother was born. I look to the balcony, to the room where she entered the world. I see her. She waves.

The bus picks up speed.

The bus hurries past familiar houses, past shops, past families walking the crooked pavements. They are blurred. The buildings vary in size, in purpose; they are known, almost untouched, unaltered during the missed years.

I smile.

The bus stops. Its final destination.

Disg

~nine

Malta’s top 5: Churches and Cathedrals

* 5. The Rotunda of St Marija Assunta, Mosta

The magnificent dome is said to be third largest in Europe and was targeted during World War II. While a congregation prayed, a bomb penetrated the dome and fell to the ground, yet no one was harmed. The bomb is displayed within the church.

I walk to the stone steps, those in front of the church of Mosta whose dome dominates the beautiful skyline of my island. The steps are insignificant, lost beneath the mighty church. The Rotunda of St Marija Assunta, Mosta marks the heart, the soul, the essence of the island.

I sit down.

I am on the top step.

my feet are moving.

~p – it – ter.

~p – it – ter.

pattering, restless.

I am looking at my ruby red toenails, at the cracks in the layers, the imperfections. I always do that; I know that Matt would agree. I see negatives in myself, beauty in others. I wish that I had thought to remove the nail varnish, to repaint my toenails and then I laugh, ha ha ha. I had not planned this journey, I had not thought.

My toes are covered in a fine layer of white dust, Maltese dust, the leftovers of lives. A fine layer of white dust has already settled onto the smooth steps; I wonder which fragments of lives, of memories exist beside me, covering me. Some of the remnants will be lost within the white cotton of my dress. I think, I will not wash my dress.