Полная версия

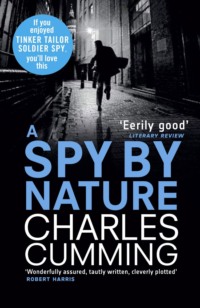

A Divided Spy: A gripping espionage thriller from the master of the modern spy novel

It was Rafal Suda.

Kell fixed his eyes back on Riedle and smiled a crocodile smile. If the German looked down, he would see Suda. It was that simple. The man who had mugged him only two nights earlier was standing less than eight feet away, making audible small talk with the maître d’. If Riedle recognized him, there would be a confrontation. There would be police involvement and Kell would be obliged to act as a witness. The operation would be over before it had begun. Any hope of locating Minasian by using Riedle as a lure would evaporate.

In an effort to keep the conversation flowing, Kell repeated his assertion that Riedle was lucky to be free of Dmitri, a man who had exerted such a baleful influence over his private life. He spoke for as long as it took for Suda and his date to be led towards the interior of the restaurant. When they were beyond Riedle’s line of sight, Kell encouraged the German to respond. As he listened to his reply, Kell could see Suda, out of the corner of his eye, being led to the first table on the parallel balcony. He was no further away than the length of a London bus. It was a slice of wretched luck. Forgeron had seating for up to a hundred customers in the main section towards the back of the restaurant, but Suda had been seated in one of the few places from which he could still be seen by Riedle.

The German was talking. Kell was trying to absorb what he was saying about Minasian while simultaneously formulating a plan for getting Suda out of the restaurant. A warning text message would do it, but Suda would almost certainly have abandoned the mobile he had used on the Riedle operation. Kell had no other number, only an email address. What were the chances of a middle-aged Polish spook checking his inbox while a statuesque blonde was gazing adoringly into his eyes over a platter of oysters? Slim, at best. No, he had to think of an alternative approach – and all the while keep Riedle talking.

‘What were Dmitri’s politics?’ he asked. Kell looked down at Riedle’s plate. The German had almost finished his lamb cutlets. That was the next problem. With a kir and several glasses of wine inside him, a man of Riedle’s age might need to go to the bathroom in the break between courses. Should he do so, he would need to turn around and to inch along the balcony, all the while looking out over the restaurant, directly towards Suda’s table.

‘He rarely spoke about politics,’ he said. ‘I asked him, of course, and we had arguments about what was going on in Ukraine.’

‘What kind of arguments?’

‘Oh, the usual ones.’ Riedle speared a stem of purple-sprouting broccoli, no more than two or three mouthfuls left before he would finish. ‘That Crimea should be restored to Russia, that it was given to Kiev without permission by Khrushchev …’

‘I would agree with that,’ Kell replied.

‘But I saw the separatist aggression in the east as a senseless waste of lives, innocent people dying for the cause of meaningless nationalism.’

‘I would also agree with that,’ Kell concurred, desperately scrabbling for ideas. He felt like a public speaker with ten more minutes to fill and not an idea in his head. ‘And what we’ve been seeing in Russia is the extraordinary success of the Kremlin propaganda machine. There are educated, liberal intellectuals in Moscow who believe that Ukrainian soldiers have crucified Russian children, that any opposition to Russian influence in the region has been orchestrated by the CIA …’

The use of ‘we’ was a hangover from Office days, the party line at SIS. Kell had made a mistake. Riedle, thankfully, appeared not to have noticed. Instead he nodded approvingly at what Kell had said and then – Kell felt the dread again – turned in his seat and looked down towards the entrance, distracted by a movement or sound that Kell had not detected.

‘But otherwise he wasn’t a political animal?’ Kell asked, trying to bring Riedle’s eyes back to the table. It had been a mistake to ask about politics. Riedle was a sensualist, an emotional man in the grip of heartbreak. He didn’t want to be talking about civil wars. He wanted to be talking about his feelings.

‘No, he was not. He had studied political philosophy at Moscow University.’

A waiter brought a bottle of champagne to Suda’s table. When the cork popped, Riedle might turn around. All of Kell’s energy was directed at preventing that from taking place. He needed to hold Riedle in a sort of trance of conversation, to make it impossible for him to look away.

‘What was his job?’ Kell asked. He removed his jacket in the gathering heat.

‘Like you,’ Riedle replied. ‘Private investment. Raising financing for different projects around Europe.’

A classic SVR cover.

‘Which allowed him to travel extensively? To spend time with you?’

The woman was giggling, Suda raising a loud toast.

‘Precisely.’ Something had caused Riedle to smile. ‘It’s funny. I always felt like the sophisticated one. The older Western European intellectual teaching the boy from Russia. This was false, of course. Dmitri was much cleverer, much better educated than I am. But he was often very quiet. I used to think of it as shyness. Now I think of it as a lack of something.’

‘He sounds like somebody with very little generosity of spirit.’

‘Yes!’ Riedle almost thumped the table in enthusiastic endorsement of Kell’s insight. ‘That is exactly what he was like.’

‘Generosity of spirit is so rare,’ Kell said, continuing to improvise conversation. Could he send a note via a member of staff? Not a chance. Nor could he leave Riedle alone at the table; the German might use the time to start gazing around the restaurant. ‘If a person is essentially self-interested,’ Kell said, moving a floret of cauliflower in slow circles around his plate, ‘if their only goal is the satisfaction of their own vanity, their own appetites, even at the expense of friends or loved ones, that can be enormously distressing for the person left behind.’

‘You understand a great deal, Peter,’ Riedle replied, lifting a final mouthful of lamb towards his gaping mouth. Kell watched the rising fork as he might have watched a clock ticking down to zero hour. He was convinced that Riedle was going to leave the table as soon as he had finished eating. ‘Tell me about your own experience,’ Riedle asked. ‘Tell me how you coped with the end of your marriage.’

If it would guarantee the German’s undivided attention for the next hour, Kell would happily now have told him the most intimate and scandalous details of his relationship with Claire. Besides, wasn’t it one of the golden rules of recruitment? Share your vulnerabilities. Confide in a prospective agent. Tell him whatever he needs to hear in order to establish complicity. But before he had a chance to answer, Riedle added a coda.

‘First, however, will you excuse me?’ He was dabbing his mouth with his napkin and preparing to stand up. ‘I must go to the bathroom.’

At that same moment, Kell looked across the room and saw Rafal Suda in the midst of precisely the same ritual. The dabbed napkin. The soundless request to his companion. It was as though the two men had made a secret plan to meet. Rising to his feet, Suda laughed as his date cracked a toothy joke. If Riedle left now, he would bump into Suda within thirty seconds.

‘Would you mind if I went first?’ Kell asked and did something that he had never done in all his life as an intelligence officer. He clutched at his waist and pretended to be hit by a searing pain in his stomach.

‘But of course,’ Riedle replied, settling back into his seat. ‘Are you all right, Peter?’

Kell struggled to his feet, wincing in apparent agony. ‘Fine,’ he gasped, ‘Fine’, and ducked to avoid a low-hanging lamp. ‘Happens from time to time. Just give me five minutes will you, Bernie? I’ll be right back.’

12

Kell was only a few feet behind Suda as he walked into the bathroom. A man in a dark grey suit came out at the same time and held the door for him as they passed.

‘Merci,’ Kell said, going inside.

Suda was standing at a urinal, staring down into the bowl. He was alone in the room. There were two cubicles beyond him, both of which Kell checked for occupants before lighting the blue touchpaper.

‘What the fuck are you doing here?’

Suda looked back, urinating, and swore in Polish.

‘Tom.’

‘I’m eating dinner ten feet away from your fucking table with Bernhard fucking Riedle. Why are you still in Brussels?’

The shock oozed into Suda’s face as he began to reply, his blue-black birthmark creased with fatigue. Still urinating, he was unable fully to turn around. Kell was riding the adrenaline of the previous fifteen minutes and did not hold back.

‘You realize if he sees you, I’m fucked? You realize if he so much as turns around and looks at your underage, I-still-haven’t-graduated-from-high-school girlfriend and recognizes the man sitting opposite her, that my operation – for which you were extraordinarily well paid and which has cost me outside of ten thousand pounds and almost two weeks of planning – will not only be over, but will involve you being arrested in front of a room full of people carrying iPhones – iPhones with cameras and zoom lenses and microphones – and me standing right beside Riedle as he asks me to positively identify the street criminal who tried to mug him two nights ago?’

Suda was zipping up his trousers and trying to interrupt, but Kell wasn’t done.

‘I’m not interested what excuse you have, why you felt that you had to stay in Brussels with your newly adolescent, fake eyelash, breast-enhanced babysitter, rather than go home to your wife and children in Warsaw as you promised me you would do when I hired you, but here’s what’s going to happen, Rafal. There’s a kitchen outside. You go into it. You walk very quickly and very confidently to the back of that kitchen and you leave by any exit possible. You leave the way the staff leave. If anybody tries to stop you, pay them. Do you have money?’

Suda nodded. It was like scolding a schoolboy who had been caught cheating in an exam.

‘Good,’ he said. ‘I will tell a waiter that I saw you leaving, that you had to go out the back because your wife had walked into the restaurant and that you gave me money. I will pay your bill. The waiter will then explain to Kim Kardashian that you’re waiting for her outside. Maybe she’ll finish her oysters. Maybe she won’t. You can call her. Do what you want. But if you don’t get out of here and get permanently out of Riedle’s sight, I will personally see to it that no intelligence agency, no corporate espionage outfit, no police department, no bank or multinational will ever give you any business again. You won’t teach. You won’t drive cabs. You won’t change a fucking lightbulb in this shitty Belgian bathroom. All you will do is get out of this restaurant. Do not pass go. Do not collect two hundred pounds. Leave.’

13

Suda did as he was told.

Kell watched him walk briskly through the swing doors of the kitchen and waited outside to make sure that he did not double back. He then took the maître d’ to one side, explained that he had met a man in the bathroom who was at risk of being compromised by his wife while dining with his mistress, paid Suda’s bill in cash, tipped the maître d’ a further twenty euros to break the news gently and discreetly to the girlfriend, then made his way back to Riedle.

Several minutes had passed since Kell had left the table, but the German was relaxed and companionable, fussing and fretting over Kell’s condition. Have you had these incidents before? Do you require a doctor? Perhaps it was something in your food? Kell brushed aside his concerns, realizing – as their conversation continued – that Minasian would almost certainly have taken advantage of Riedle’s innate decency; there was a neediness about him, a desire to win affection through acts of kindness and generosity, which to a sadist like Minasian would have been like the scent of blood to a shark.

‘I was thinking, while you were away, that I feel rather ashamed.’

‘Ashamed, Bernie? Why?’

Kell wondered why Riedle hadn’t yet taken the opportunity to go to the bathroom. His napkin was still balled on the table.

‘It is embarrassing for a man of my age, a man almost sixty, to be at the mercy of an infatuation, don’t you think? To be so broken-hearted. So weak. I feel like a fool.’

‘Don’t,’ Kell replied firmly, and tried to comfort Riedle with a gentle smile. ‘I think it shows that you are alive. That you haven’t given up on people, become stale or jaded.’ Riedle asked him to translate the word ‘jaded’ and Kell offered ‘tired’ as a lazy synonym. ‘We all have a need for company. Most of us, anyway. What you are going through speaks to our deep need to feel connected, to share our lives with somebody who understands us, who makes us feel cherished. We want to feel free to be who we are. We want somebody who will help to open up the best side of ourselves.’

Rachel flooded Kell’s memory, her poise and her laughter, the way in which she had so quickly intuited so much about him. He felt the loss of her as a pain every bit as searing as that which he had faked only ten minutes earlier, clutching his stomach for Riedle’s benefit.

‘To care for somebody and to be cared for,’ Kell continued, now thinking of Claire and of everything that had gone missing between them. ‘To be excited about seeing them, hearing what they have to say, talking to them. Isn’t that what it’s all about? You obviously had that with Dmitri, when things were good between you. A person can be fifty-nine or nineteen and experience those things. There’s no shame in mourning them when they have been taken away from you.’

‘Then I thank you for your understanding,’ Riedle sighed with a gesture of collapsing gratitude, and finally stood up to go to the bathroom.

As he inched along the walkway, Kell looked across to the opposite balcony, where the maître d’ was only now informing Suda’s companion that her date had left for the evening via the back door. She took the news with laudable restraint, checking her face in a compact mirror before standing up, adjusting her hair and walking downstairs. As she tottered to the ground floor on four-inch heels, she took a smartphone from her purse and checked the screen for messages. At the same moment, Kell felt his own phone pulse in his trouser pocket.

It was a text from Suda.

I will tell Stephanie that it was a Polish police matter, not anything to do with my wife.

Tell her what you like, Kell muttered as a second text came in.

I will take her to Hotel Metropole. I apologize, Tom. My plane leaves for Warsaw at 8 tomorrow. In the morning.

Kell deleted the messages without replying and watched Stephanie collect her coat at the entrance. She must have felt his gaze because she looked up and stared at Kell, an almost imperceptible tremor of longing in her eyes. A beautiful young woman aware of her power over men, and testing it all the time. Kell thought of her in Rafal’s arms in a bed at the Hotel Metropole. Then he thought of Rachel and Claire, of Riedle and Minasian, of the whole sorry dance of sex and yearning, of love and betrayal.

There was one more glass of wine left in the bottle of Chianti. He finished it.

14

The two men walked home together, Riedle bidding farewell to Kell in the lobby of the apartment building where, just two days earlier, they had met for the first time. Kell rode the lift to the fourth floor, already taking the pen from his jacket pocket with which he would write down detailed notes about the dinner. It was an old habit from Office days. Get home, write up the telegram, no matter how late at night, then send it to London.

Kell entered the apartment. He was hanging up his jacket when he heard a cough from the living room. Walking inside, he saw Mowbray sitting on the sofa, a glass of single malt in front of him and a grin on his face like Arsenal had won the European Cup in extra time.

‘You’re looking very pleased with yourself, Harold.’

‘Am I, guv? Well, that makes sense.’ He leaned further back on the sofa. ‘How was your dinner? Bernie try and hold your hand?’

‘Very funny.’

‘Seriously, you wanna be careful, boss. Bloke like that, lonely and unhappy. Nice, good-looking British diplomat comes along, listens to his sad stories, protects him from antisocial elements on the mean streets of Brussels. He might be falling in love with you.’

Kell was pouring a whisky of his own and felt a sting at the edge of his vanity. He didn’t normally mind Mowbray’s joshing, but liked to maintain a level of hierarchical respect in his dealings with colleagues.

‘So why are you looking so smug?’ he asked, sitting in an armchair at right angles to the sofa. Kell kicked off his shoes, trusting his memory sufficiently to be able to write the report in an hour’s time.

‘Did Bernie say anything about how he used to contact lover boy?’

Kell shook his head. ‘We haven’t got that far yet. First night I met him he mentioned something about a friend “always losing his phones and changing numbers”. I assumed that was Minasian, that he had four or five different mobiles he used for contacting Riedle. Why do you ask?’

Kell took a sip of his whisky, sensing that Mowbray had made a breakthrough. The communications link between Riedle and Minasian was the holy grail of the operation. Find that and they could start to track the Russian, to lure him across the Channel to London.

‘I think I’ve cracked it,’ he said.

Kell moved forward. ‘Tell me.’

‘You know I put key-log software in his laptop? Every password entered, every sentence typed.’

‘Sure.’

There was a laptop on the table in front of them. Mowbray opened it up. ‘So it turns out they kept it simple. Least as far as email is concerned. I’ve been able to hack into his account. They encrypted their messages.’

It was the smart play, the easiest and most secure way for Minasian to communicate with Riedle without raising his suspicions or drawing the attention of the SVR.

‘PGP?’ Kell asked, an acronym for a popular piece of encryption software that he understood in only simple terms.

‘Very good!’ Mowbray replied, amazed that Kell – who was famously antediluvian when it came to technology – was even aware that PGP existed. ‘So Elsa got hold of the private key which Bernie stored on his laptop and Bob became my uncle. After that it’s just like reading a normal email correspondence.’

Mowbray swivelled the laptop towards Kell and said: ‘Take a look.’ There were three emails sitting in the account: two from Riedle, one from Minasian. Kell assumed that the others had been deleted or filed elsewhere. As Mowbray stood up and went outside on to the balcony to smoke a cigarette, Kell clicked on the most recent message.

It was dated ten days earlier and had been given the headline ‘Betrayal’. It was both a plea from Riedle, begging Minasian to come to Brussels so that they could patch things up, and a sustained attack on his character and behaviour. Reading it, Kell felt as if he was intruding on a private grief so intense as to be almost embarrassing in its candour.

You are not the man I recognize, the man I love. You are so cruel to me, so hard and objective. What happened to us? Your attitude when we talked on the phone yesterday degraded everything that we once shared.

That phrase – ‘when we talked on the phone’ – was as welcome to Kell as water in a drought, because it held out the possibility that Minasian would risk contacting Riedle again, perhaps making a call on Skype that Mowbray’s microphones would pick up.

You coldly announce that you are still in love with Vera, that you are now disgusted by your true sexuality, by what passed between us. How do you think that makes me feel? You tell me that you still love her, that you now find Vera attractive, when we both know this is a lie. You have never wanted to be with her in that way. Why now? Why the change? Then you told me on the telephone that you feel more relaxed in her company than you ever did with me. What kind of a person says those things?

A sociopath says those things, thought Kell. Someone incapable of compassion, of feeling anything but contempt for those who might ask something of them.

I always admired your commitment to the ‘truth’. There had been so many lies in my own life when we met that I found your determination to act honestly in all things captivating. But I realize now that you are a hypocrite. Your ‘truth’ is just what suits you at the time. It disguises your ruthlessness, because you are indeed ruthless and unkind. You lie to Vera, you lie to me, you lie to your unborn children. You lie to yourself.

Kell no longer knew if he was reading the email for operational reasons or purely out of human fascination. He worried that Riedle’s anger and spite, if it continued, would drive Minasian further and further away. At times he sounded like a man who had lost all reason and context.

You have left me, but you have not tried to soften the blow or to use the simple white lies people use in these situations when they care about not hurting a lover. What I hope for, what I need, is a small amount of compassion, of kindness, some sense that what we have been through together over the past three yearsmeanssomething to you. All I am asking for is a sense that you understand and are sensitive to the depth of my love for you. You know, better than anyone has ever known, how I think and how I feel and how difficult my life is now that you are not in it – and yet you treat me as if I was no more important to you than a boy picked up in a sauna.

There was more. Much more. The suggestion that Minasian, a year earlier, had been introduced to one of Riedle’s friends and had slept with him. The accusation that he had taunted Riedle continuously with stories about the men (and women) he met in different European cities while working for the bank. There had clearly been a sado-masochistic element to the relationship which Minasian had encouraged and enjoyed. Added to what Riedle had told Kell at dinner about Minasian’s aggressive, sullen behaviour, the relationship amounted to a catalogue of emotional abuse. Kell wanted to go downstairs, to knock on Riedle’s door, ask him why the hell he had put up with it for so long, and then pour him a large Scotch.

He clicked to the second email. It was, as Kell expected, a brief reply from Minasian, written four days after Riedle’s message, with no Subject line. The language was distant, cold and supremely controlled.

I hoped that you would behave with more dignity, more courage. If you write to me like this again I will have nothing more to do with you. I refuse to engage with your insults and accusations.

Kell noted the absence of any consoling words. Nothing to acknowledge Riedle’s pain or the accusation of infidelity. Nevertheless, Minasian was holding out the possibility of further interaction in the future.

Riedle had replied within twelve hours. Kell clicked to this final email.

I am very sorry. I was angry. Please don’t vanish. I am happy to be friends. I just want to keep you in my life and to try to understand what is happening to us.

You are so strong. I don’t think you have ever known heartbreak. I know that you have felt isolated and alone. I know that you have felt a panic about the structure of your life. But you have never known what it is to feel passed over, exchanged – the madness of loss. You have never lost somebody that you were not ready to lose, a person who felt, as I do, that you were holding his entire happiness in the palm of your hand. It’s like you have closed your hand. Made a fist. I need to be treated with delicacy, with kindness and compassion. Please provide this. I am begging you.

I am very sorry for the things I said. I did not mean them. Please consider what I said about Brussels. I can come and meet you anywhere, even if it’s just for lunch (or a cup of coffee!) In Egypt you said you had a period coming up in Paris. That would be perfect – I can be at the Gare du Nord in less than two hours from Brussels.