Полная версия

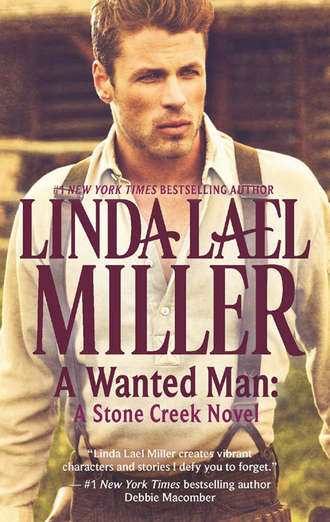

A Wanted Man: A Stone Creek Novel

To his surprise she gave a soft laugh.

“You are a dear,” she said fondly.

Rowdy was both amused and disturbed to realize he wished she’d been talking to him instead of the dog.

* * *

LARK WATCHED FROM the steps of the schoolhouse that Monday morning as Maddie O’Ballivan, carrying her infant son in one arm and steering his reluctant older brother, Terran, forward with the other, marched through the gate. Ben Blackstone, the major’s adopted child, followed glumly, his blond hair shining in the morning sunlight.

Behind the little procession sat a wagon with two familiar horses tied behind. It had been the sound of its approach that had caused Lark to interrupt the second-grade reading lesson and come out to investigate.

Class had begun an hour earlier, promptly at eight o’clock.

Lark had missed Ben and Terran right away, when she’d taken the daily attendance, and hoped they were merely late. It was a long ride in from the large cattle ranch Sam and Major Blackstone ran in partnership, and for all that those worthy men must have deemed the journey safe, there were perils that could befall a pair of youths along the way.

Wolves, driven down out of the hills by hunger, for one.

Outlaws and drifters for another.

“Go inside, both of you,” Maddie told the boys when she reached the base of the steps. Samuel, the baby, had begun to fuss inside his thick blanket, and Maddie bounced him a little, smiling up at Lark when Terran and Ben had slipped past her, on either side, to take their seats in the schoolroom.

“Rascals,” Maddie said, shaking her head and smiling a little. “They were planning to spend the day riding in the hills—I guess they didn’t figure on Sam and the major heading into town for a meeting half an hour after they left, and me following behind in the buckboard, meaning to lay in supplies at the mercantile.”

Maddie was a pretty woman, probably near to Lark’s own age, with thick chestnut hair tending to unruliness and eyes almost exactly the same color as fine brandy. Until the winter before, according to Mrs. Porter, Maddie had run a general store and post office in a wild place down south called Haven. She’d married Sam O’Ballivan after the whole town burned to the ground, and borne him a son last summer. Lark’s landlady claimed the ranger’s bride could render notes from a spinet that would make an angel weep, but she’d politely refused to play on Sunday mornings at Stone Creek Congregational. Said it was too far to travel, and she had her own ways of honoring the Lord’s Day.

Lark liked Maddie O’Ballivan, though they were little more than acquaintances, but she also envied her—envied her home, her obviously happy marriage and her children. Once, she’d fully expected to have all those things, too.

What a naive little twit she’d been, with a head full of silly dreams and foolish hopes.

“No harm done,” Lark said quietly, smiling back at Maddie. “I’ll give them each an essay to write.”

Maddie laughed, a rich, quiet sound born of some profound and private joy, patting the baby with a gloved hand as she looked up at Lark, her eyes kind but thoughtful. “You’re cold, standing out here. I’ll just untie Ben and Terran’s horses, so they’ll have a way home after school, and be on about my business.”

“I’ll send the boys out to do that,” Lark said, hugging herself against the chill. She hated to see Maddie go—she’d been lonely with only Mrs. Porter and Mai Lee for friends—but she had work to do, and she was shivering.

“Miss Morgan?” Maddie said, when Lark turned to summon Terran and Ben to see to their horses.

“Please,” Lark replied shyly, turning back. “Call me Lark.”

“I will,” Maddie said, pleased. “And of course you’ll call me Maddie. I was wondering if you might like to join Sam and me for supper on Friday evening. You could ride out to the ranch with the boys, after school’s out, or Sam could come and get you in the wagon.”

Lark flushed with pleasure; in Denver, as the wife of a powerful and wealthy man, she’d enjoyed an active social life. In Stone Creek, she was a spinster schoolmarm, and she probably roused plenty of speculation behind closed doors. Since she was a stranger and had all the wrong clothes for her station in life, folks seemed reticent around her. No one invited her anywhere, and she hadn’t thought it proper to attend community dances; she didn’t want the parents of her students thinking she was forward or looking for a husband.

“I’d like that,” she said. “But I don’t ride.”

Maddie smiled. “I’ll send Sam, then. Go inside now, before you freeze.”

Lark nodded and went back into the schoolhouse. She told Terran and Ben to go out and unhitch their horses, and they scrambled to obey.

“Miss Morgan?” A small hand tugged at the side of her skirt, and she looked down to see Lydia Fairmont holding up a page torn from her writing tablet. “I copied the words off the blackboard. Will you tell me if all my letters are headed whence they ought to go, please?”

* * *

AS AGREED, ROWDY met Sam and the major in the lobby of the small, rustic Territorial Hotel, the only such establishment in Stone Creek, just before nine o’clock that morning. He’d walked over with Pardner from Mrs. Porter’s, having left his horse at the livery stable the night before after returning from Flagstaff.

Both men stood when he entered, Sam looking fit and a little grim, though he had the peaceful eyes of a happily married man. Rowdy had never met the major, only seen him briefly when he’d come to Haven on sad business over a year before.

“Thanks for making the ride up here,” Sam said, sparing a slight smile for Pardner as he and Rowdy shook hands. “Good to know your sidekick is still with you.”

Rowdy nodded, then turned to the major, a tall, broad-shouldered man with a full head of white hair and a face like a Scottish banker.

“Major Blackstone,” Rowdy said respectfully.

“Call me John,” the major said, his voice deep and gruff.

“That would be an honor, sir,” Rowdy replied. Blackstone was a legend in the Arizona Territory and beyond—before signing on with the rangers, he’d led cavalry troops at Fort Yuma. In his spare time, he’d founded one of the biggest spreads that side of Texas, fit to rival the McKettrick ranch over near Indian Rock, and served two terms in the United States Senate.

Sam had told Rowdy some of these things back in Haven. Rowdy had made a point of finding out more after receiving the telegram.

They all sat down in straight-backed leather chairs pulled up close to the crackling blaze on the hearth of a large natural-rock fireplace. The lobby was otherwise empty and silent except for the ticking of a long-case clock. Pardner stuck close to Rowdy and lay down near his feet.

Rowdy saw Sam sit back, clearly taking his measure, and Pappy’s anxious words came back to him with an unexpected wallop. First, last and always, Sam O’Ballivan is an Arizona Ranger. You have truck with him, and you’re likely to find yourself dangling at the end of a rope.

“I guess you know the railroad is headed this way from Flagstaff,” the major ventured, after clearing his throat like a man preparing to make a speech.

Rowdy felt a quiver in the pit of his stomach. It wasn’t fear, just a common-sense warning. “So I’ve heard,” he said moderately.

Sam finally spoke. “Maybe you know there’s been some trouble. A couple of train robberies out of Flagstaff.”

With just about anyone else, Rowdy might have feigned surprise. With Sam O’Ballivan the trick probably wouldn’t work. “Heard that, too,” he said.

“According to Sam here,” the major went on, “you made a pretty fair lawman, down there in Haven. Stayed on after the fire, and all that trouble with that gang of outlaws. Shows you’ve got some gumption.”

Rowdy did not respond. Blackstone and O’Ballivan had issued a summons, and he’d honored it. It was up to them to do the talking.

“We need your help,” Sam said forthrightly. “The major’s getting on in years, and I’ve got a wife and family to look after, along with a sizable herd of cattle.”

“What kind of help?” Rowdy asked.

“Rangering,” John Blackstone said.

Wait till Pappy hears this, Rowdy thought. Not that he’d get a chance to share the information in the immediate future. “Rangering,” he repeated.

“I can swear you in right now,” the major announced. “’Course, that part of things will have to be our secret. Pete Quincy, the town marshal, up and quit a month ago, and you’d be filling his job, far as the good people of Stone Creek are concerned. The job doesn’t pay worth a hill of beans, but it comes with a decent house and a lean-to barn behind the jail, and you can take your meals at Mrs. Porter’s if you aren’t disposed to cook.”

Rowdy swept the room with his gaze. The hotel seemed as empty as a carpetbagger’s heart, but if they looked around a few corners or behind the curtains, they’d probably find Mrs. Porter, or someone of her ilk, with ears sticking out like the doors of a stagecoach fixing to take on passengers.

Sam interpreted the glance correctly. “There’s nobody here,” he said.

“You seem mighty sure of that,” Rowdy replied easily.

“Cleared the place myself,” Sam answered.

Rowdy tried to imagine anybody staying when Sam O’Ballivan said “go,” and smiled. “All right, then,” he said. “If I understand this correctly, I’m to pose as the marshal, but I’ll really be working for the major, here.”

“John,” the major said firmly.

“John,” Rowdy repeated.

“You’ve got the right of it,” Sam said. “All the while, of course, you’ll be keeping your ear to the ground, same as John and I will, for anything that might lead us to this train-robbing outfit.”

Rowdy chose his words carefully. “Might not be an outfit,” he offered. “Could be random—drifters, or drunked-up cowpokes looking to get a grub stake.”

John and Sam exchanged glances, then Sam shook his head.

“No,” he said. “It’s not random. Both robberies were carefully planned, and carried out with an expertise that can only come with long experience. These men aren’t drifters—they’re too sophisticated for that. The first robbery was peaceable. They felled a couple of trees across the track, in a place where the engineer would be sure to see the obstruction soon enough to put the brakes on. But there was a railroad agent aboard the second train, and the robbers seemed to know him. Singled him out right away, and relieved him of his weapons. A passenger tried to intercede, and he was shot for his trouble. Might never regain the use of his right arm.”

“You suspect anybody in particular?” Rowdy asked lightly.

“All we’ve got is a hunch,” John said. “My gut tells me, this is Payton Yarbro and his boys.”

Rowdy did not react visibly to the name—he’d had too much practice at hiding his identity for that—but on the inside, things commenced to churning. “I haven’t heard anything about the Yarbros in a long time,” he said. “I guess I figured they’d scattered by now. Even gone out of business. The old man’s got to be getting pretty long in the tooth—might even be dead.”

Both Sam and John were silent, and the speculation in their eyes unnerved Rowdy. He realized that if he’d followed his first impulse, which was to pretend he’d never heard of the Yarbros, they’d have been suspicious. Not to know of the Yarbros would have been the same as not knowing who the James brothers were, or the Earps.

“It’s only fair to tell you,” Rowdy went on, “that I’ve got no experience tracking train robbers. I sort of stumbled into that marshaling job down in Haven, and just did what was there to do. I’ve been a ranch hand, mostly.”

Sam watched him for a long moment, and with an intensity that would have made anybody but a Yarbro squirm in his chair. On the off chance Sam knew that, Rowdy shifted slightly.

“Sam tells me you’re a good hand in a gunfight,” John said. “You could have lit out when things got rough in Haven, but you stayed on. Even helped with some of the rebuilding, along with wearing a badge. You’ve got the kind of grit we’re looking for.”

Rowdy’s hat rested in his lap. He turned it idly by the crown. “I’m not inclined to settle down permanently,” he said.

The major nodded once, decisively. “That’s your prerogative. Run the Yarbros to ground and ride out, if that’s what you want to do. We’d be glad to have you stay on in Stone Creek, though.”

Rowdy studied John Blackstone. “You sure do seem to think highly of me,” he remarked, “given that I’m a stranger to you, and all you’ve got to go on is my reputation.”

For the first time since the palaver had begun, Blackstone smiled. “I’d stake my life and everything I own on Sam O’Ballivan’s assessment of anybody’s character. I might not know you from Adam, but I sure as hell know Sam.”

Rowdy knew Sam, too, and that was what made him wary. He was a fast gun, maybe as fast as Rowdy was, and he had a fortitude rarely seen, even in the wild Arizona Territory. Of course, it was possible, too, that Sam had already pegged Rowdy for a Yarbro, and meant for him to lead them right to Pappy’s den.

A more prudent man would have taken his pa’s advice and ridden out, put as much distance between himself and Stone Creek as he could, pronto. Rowdy was a gambler at heart; he wanted to stay and see how the cards would fall, but that wasn’t his main reason for sitting in on this particular game.

He had another, even more intriguing puzzle to solve, and that was Lark Morgan, though there was no telling when she’d strike out for parts unknown.

Sam and the major sat waiting for him to announce his decision, though they probably already knew what it would be.

“I’ll see what I can do,” he said.

“Good,” John replied, with the air of a man completing important business. “I’ll swear you in as marshal, and Sam’s got a badge in his pocket. You just remember, the rangering part is between us.”

“I might need a posse, if I’m going after a bunch of train robbers,” Rowdy said. Whatever his private differences with his pa, he had no intention of rounding the old man up for a stretch in the prison down in Yuma, or even a hangman’s noose, but he’d put on a show until he knew what was what.

There was an off chance, of course, that Payton had been telling the truth when he claimed he’d had no part in robbing those trains. Should time and some investigation bear him out, Rowdy would find the real culprits and bring them in.

“If a posse is called for,” Sam said, handing Rowdy a star-shaped badge, “we’ll get one up.”

When the major produced a battered copy of the New Testament, Rowdy didn’t hesitate to lay a hand on it. He wasn’t a believer—at least, not the usual kind—but his mother had been, and that made the oath a solemn matter.

Fortunately, there was nothing in it about handcuffing his own pa, or any of his brothers, not specifically, anyhow. He swore to uphold the law, and he’d do that—up to a certain point.

After the swearing in, the major went off on some errand over at the Stone Creek Bank, while Sam, Rowdy and Pardner headed for the jailhouse, down at the far end of the street.

Would have made more sense to put the marshal’s office in the center of town, where the saloons were and trouble was most likely to break out. Rowdy figured folks wanted a lawman around, but at a little distance, too.

The jailhouse was about like the old one in Haven, before it burned. One cell, a potbelly stove with a coffeepot on top, somebody’s old table to serve as a desk.

It was the cabin out back that surprised Rowdy a little. It had three rooms, a good fireplace and a cookstove to rival the one in Mrs. Porter’s kitchen. The floors were hardwood and the windows were sound, with no cracks around them to let in the winter wind. The bed had a good feather mattress and plenty of blankets, and there was a sink with a working pump. An indoor toilet and a stationary bathtub with a copper hot water tank and a wood-burning boiler under it raised the place to an unexpected level of luxury.

“The last marshal had a wife,” Sam explained simply. “Come on. I’ll show you the barn.”

Rowdy grinned. “I’d probably feel more at home out there,” he said. Back in Haven he’d slept on a cell cot, when there were no prisoners, and with a certain accommodating widow when there were.

“Maybe you’ll take a wife,” Sam said, making for the back door.

“Not likely,” Rowdy replied.

Sam chuckled. “I thought the same way once,” he said. “Then I met up with Maddie Chancelor.”

4

LARK AWAKENED with a start, heart pounding, afraid to open her eyes. She was certain she would see Autry Whitman looming over her bed if she did.

The room was frigid, and the fine sweat that had broken out all over her body in the midst of her nightmare exacerbated the chill stinging the marrow of her bones. She forced herself to breathe slowly and deeply, and raised one eyelid, every muscle in her body tensed to roll off the side of the mattress and grab for something, anything, to use as a weapon.

Autry wasn’t there.

Tears of relief clogged her throat and burned on her cheeks.

Autry wasn’t there.

She sat up, fumbled with the globe of the painted glass lamp on her bedside table, struck a match to the wick. Shadows rimmed in faint moonlight receded and then dissolved. According to the little porcelain clock she’d brought with her from St. Louis, it was after three in the morning.

Inwardly Lark groaned. She wasn’t going back to sleep.

After summoning all her inner fortitude, she swung her legs over the side of the bed and stood. The wooden floor felt frosty under her bare feet, and, shivering, she thought with longing of the wood cookstove downstairs.

She would go down there, build up the fire, if it hadn’t gone out after Rowdy banked it for the night. Light another lamp and wait, as stalwartly as she could, for morning to come.

Lark grabbed up her wrapper—it was a thin silk, and therefore useless against the cold—and went out into the corridor, feeling her way along it in the gloom. She would have brought the lamp from her room, but it was heavy, and an heirloom Mrs. Porter prized. Breaking it might even be grounds for eviction, and Lark had nowhere to go.

She descended the back stairs as quietly as she could and gasped when she saw a man-shaped shadow over by the cookstove.

Autry?

Rowdy Rhodes stepped out of the darkness, moonlight from the window over the sink catching in his fair hair. He moved to the center of the room and lit the simple kerosene lantern on the table.

Lark laid a hand to her heart, which had seized like a broken gear in some machine, and silently commanded it to beat again.

“I’ve put some wood on the fire,” Rowdy said quietly, offering no apology for startling her. “Go on over and stand next to the stove.”

Lark dashed past him, huddled in the first reaching fingers of warmth, dancing a little, because the kitchen floor, like the one above stairs, was coated with a fine layer of frost.

Rowdy was fully clothed, right down to his boots.

“I th-thought you’d moved out,” Lark said. “Gone to live in the cottage behind the marshal’s office.” He’d told them about his new job at supper that evening, said he’d still be taking his evening meals at Mrs. Porter’s most nights.

He didn’t answer right away, but instead ducked into his quarters behind the kitchen and came out with a woolen blanket, which he draped around Lark’s shoulders. “I paid Mrs. Porter for a week’s lodging,” he said. “Since it wouldn’t be gentlemanly to ask for my two dollars back, I decided to stay on till I’d used it up.”

Pardner came, stretching and yawning, out of the back room. Nuzzled Lark’s right thigh with his nose and lay down close to the stove.

Rowdy dragged a chair over and eased Lark into it. Crouched to take her bare feet in his hands and chafe some warmth into them.

Lark knew she ought to pull away—it was unseemly to let a man touch her that way—but she couldn’t. It felt too good, and Rowdy’s callused fingers kindled a scary, blessed heat inside her, one she wouldn’t have wanted to explain to the school board.

“What are you doing up in the middle of the night?” Rowdy asked, leaving off the rubbing to tuck the blanket snugly beneath her feet. While he waited for Lark’s reply, he took a chunk of wood from the box, opened the stove door, and fed the growing blaze. Then he pulled the coffeepot over the heat.

“I sometimes have trouble sleeping,” Lark admitted, sounding a little choked. Her throat felt raw, and she wanted, for some unaccountable reason, to break down and weep. The man had done her a simple kindness, that was all. She was making far too much of it.

“Me, too,” Rowdy confessed, with good-natured resignation.

Heat began to surge audibly through the coffeepot. The stuff would be stout since the grounds had been steeping for hours, ever since supper.

Taking care not to make too much noise, Rowdy drew up another chair, placed it next to Lark’s.

“Makes a man wish for the south country,” he said. “It never gets this cold down around Phoenix and Tucson.”

Lark swallowed, nodded. The scent of very strong coffee laced the chilly air. “I ought to be used to it, after Denver,” she said, and then drew in a quick breath, as if to pull the words back into her mouth, hold them prisoner there, so they could never be said.

“Denver,” Rowdy mused, smiling a little. “I thought you said you came from St. Louis.”

“I did,” Lark said, her cheeks burning. What was the matter with her? She’d allowed this man to caress her bare feet. Then she’d slipped and mentioned Denver, a potentially disastrous revelation. “I was born there. In St. Louis, I mean.”

“Tell me about your folks,” Rowdy said. He left his chair, went to fetch two cups, and poured coffee for them both. Handed a cup to Lark.

She had all that time to plan her answer, but it still came out bristly. “My mother was widowed when I was seven. She and I moved in with my grandfather.” Lark locked her hands around her cup of coffee, savoring the warmth and the pungent aroma.

“Were you happy?”

Lark blinked. “Happy?”

Rowdy grinned. Took a sip of his coffee. Waited.

“I guess so,” Lark said, suddenly and profoundly aware that no one had ever asked her that question before. She hadn’t even asked it of herself, as far as she recollected. “We had a roof over our heads, and plenty to eat. Mama had a lot to do, running Grandfather’s house—he was a doctor and saw patients in a back room—but she loved me.”

“She never remarried?” Rowdy asked easily. At Lark’s puzzled expression, he prompted, “Your mother?”

Lark shook her head, telling herself to be wary but wanting to let words spill out of her, topsy-turvy, at the same time. “She was too busy to look for another husband. Men came courting at first, but I don’t think Mama ever encouraged any of them.”

“Is she still living?”

Lark swallowed again, even though she’d yet to drink any of her coffee. “No,” she said sadly. “She took a fever—probably caught it from one of Grandfather’s patients—and died when I was fourteen.”

“Did you stay on with your grandfather after that?”

Lark resented Rowdy’s questions and whatever it was inside her that seemed to compel her to answer them. “No. He sent me away to boarding school.”

“That sounds lonesome.”

Emotion welled up inside Lark unbidden. Made her sinuses ache and her voice come out sounding scraped and bruised. “It wasn’t,” she lied.

Rowdy sighed, spent some time meandering through his own thoughts.

Lark snuggled deeper into her blanket and tried not to remember boarding school. She’d loved the lessons and the plenitude of books and hated everything else about the place.

Pardner, slumbering at their feet, snored contentedly.

Rowdy chuckled at the sound. “At least he has a clear conscience,” he said easily.

“Don’t you?” Lark asked, feeling prickly again now that she was warming up a little. If Rowdy Rhodes was impugning her conscience, he had even more nerve than she’d already credited him with.