Полная версия

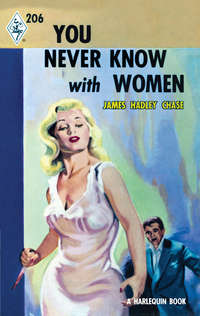

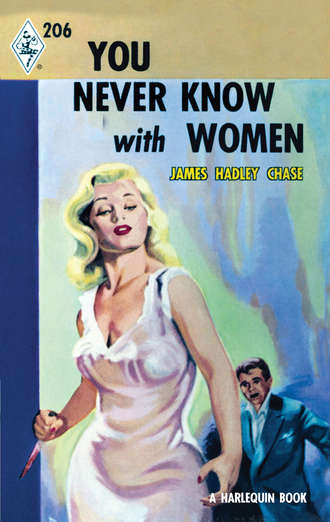

You Never Know With Women

I said I’d do it.

CHAPTER TWO

NOW THAT HE HAD ME ON THE dotted line, Gorman wasn’t giving me a chance to change my mind. He wanted me out at his place right away. It didn’t matter about going back to my rooms to pick up any overnight stuff. I could borrow anything I wanted. He had a car outside, and it wouldn’t take long to get to his place, where there were drinks and food and quiet in which to talk things over. I could see he wasn’t going to let me out of his sight now or use a telephone or check his story or tell anyone he and I had made a deal. The promise of a drink decided me. I agreed to go along with him.

But before we started we had a little argument over the money. He wanted to pay by results, but I didn’t see it that way. Finally I squeezed two of the Cs out of him and persuaded him to agree to part with two more before I did the actual job. I would receive the balance when I handed over the compact.

Just to show him I didn’t trust him further than I could throw him, I put the two bills in an envelope with a note to my bank manager, and on the way down to the street level I dropped the envelope into the mail chute. At least, if he tried to double-cross me, he wouldn’t get his paws again on those two bills.

An early-vintage Packard Straight Eight cluttered up the street outside the office. The only thing in its favor was its size. I had expected something black and glittering and streamlined to match the diamond, and this old jalopy came as a surprise.

I stood back while Gorman squeezed himself into the backseat. He didn’t get in the car: he put it on. I expected the four tires to burst as he settled himself in, but they held. After making sure there was no room in there with him, I got in beside the driver.

We roared out of town, along Ocean Boulevard, into and over the foothills that surrounded the city in the shape of a horseshoe.

I couldn’t see much of the driver. He sat low behind the steering wheel and had a chauffeur’s cap pulled down over his nose and he stared straight ahead. All the time we drove through the darkness he neither spoke nor looked at me.

We zigzagged through the foothills for a while, then turned off into a canyon and drove along a dirt road, bordered by thick scrub. I hadn’t been out this way before. Every so often we’d pass a house. There were no lights showing.

After a while I gave up trying to memorize the route and let my mind dwell on the two hundred bucks I’d mailed to the bank. At last I would have something to wave at the wolf when next he called at the office.

I wasn’t kidding myself what this job was about. I’d been hired to rob a safe. Never mind the elaborate buildup: the poor little stripper, scared of the big, bad millionaire, or the phoney dagger made by Mr. Cellini. I didn’t believe one word of that tall tale. Gorman wanted something that Brett had in the safe. Maybe it was a powder compact. I didn’t know, but whatever it was, he wanted it badly, and had come to me with this cooked-up yarn so as to have a back door to duck through in case I turned him down. He hadn’t the nerve to tell me he wanted me to rob Brett’s safe. But that’s what he was paying me to do. I had taken the money, but that didn’t mean I was going through with it. He said I was tricky and smooth. Maybe I am. I’d go along with him so far, but I wasn’t going to jump into anything without seeing where I was going to land. Anyway, that’s what I told myself, and at that time I believed it.

We were at the far end of the canyon now. It was damp down there and dark, and a thin white mist hung above the ground. The car headlights bounced off the mist and it wasn’t easy to see what was ahead. Somewhere in the mist and darkness I could hear the frogs croaking. Through the misty windshield the moon looked like a dead man’s face and the stars like paste diamonds.

The car suddenly swung through a narrow gateway, up a steep driveway, screened on either side by a high, thick hedge. A moment later we turned a bend and I saw lighted windows hanging in space. It was too dark even to see the outline of the house and everything around us was quiet and still and breathless—it was as lonely out there as the condemned cell at San Quentin.

A light in a wrought-iron coach lantern sprang up over the front door as the car pulled up with a crunch of tires on gravel. The light shone down on two stone lions crouching one on either side of the porch. The front door was studded with brass-headed nails and looked strong enough to withstand a battering ram.

The chauffeur ran around to the rear door and helped Gorman out. The light from the lantern fell on his face and I looked him over. There was something about his hooked nose and thick lips that struck a chord in my memory. I’d seen him somewhere before, but I couldn’t place him.

“Get the car away,” Gorman growled at him. “And let us have some sandwiches, and remember to wash your hands before you touch the bread.”

“Yes, sir,” the chauffeur said and gave Gorman a look that should have dropped him in his tracks. It wasn’t hard to see he hated Gorman. I was glad to know that. When you’re playing it the way I had it figured out, it’s a sound thing to know who is on whose side.

Gorman opened the front door, edged in his bulk and I followed. We entered a large hall; at the far end was a broad staircase leading to the upper rooms. On the left were double doors to a lounge.

No butler came to greet us. No one seemed interested in us now we had arrived. Gorman took off his hat and struggled out of his coat. He looked just as impressive without the hat, and as dangerous. He had a bald spot on the top of his head, but his hair was clipped so close it didn’t matter. His pink scalp glistened through the white bristles so you scarcely noticed where the hair left off.

I tossed my hat on a hall chair.

“Come in, Mr. Jackson,” he said. “I want you to feel at home.”

I went with him into the lounge. Walking at his side made me feel like a tug bringing in an ocean liner. It was a nice room with a couple of chesterfields in red leather and three or four lounging chairs drawn up before a fireplace big enough to sit in. On the polished boards were Persian rugs that made rich pools of color, and along the wall facing the French windows was a carved sideboard on which displayed a comprehensive collection of bottles and glasses.

A thin, elegantly dressed man pulled himself out of a lounging chair by the window.

“Dominic, this is Mr. Floyd Jackson,” Gorman said; and to me he went on, “Mr. Dominic Parker, my partner.”

My attention was riveted on the bottles, but I gave him a nod to be friendly. Mr. Parker didn’t even nod. He looked me over and his lips curled superciliously and he didn’t look friendly at all.

“Oh, the detective,” he said with a sneer, and glanced at his fingernails the way women do when they’re giving you the brush-off.

I hitched myself up against one of the chesterfields and looked him over. He was tall and slender, and his honey-colored hair was taken straight back and slicked down. He had a long, narrow face, washed-out blue eyes and a soft chin that would have looked a lot better on a woman. From the wrinkles under his eyes and a little sag of flesh at his throat, I guessed he wouldn’t see forty again.

He was a natty dresser, if you care for the effeminate touch. He had on a pearl-gray flannel suit, a pale green silk shirt, a bottle-green tie and reverse calf shoes of the same color. A white carnation decorated his buttonhole and a fat, oval, gold-tipped cigarette hung from his over-red lips.

Gorman had planted himself in front of the fireplace. He stared at me with empty eyes as if he were suddenly bored with me.

“You’d like a drink?” he said, then glanced at Parker. “A drink for Mr. Jackson, don’t you think?”

“Let him get it himself,” Parker said sharply. “I’m not in the habit of waiting on servants.”

“Is that what I am?” I asked.

“You wouldn’t be here unless you were being paid, and that makes you a servant,” he told me in his supercilious voice.

“So it does.” I crossed over to the sideboard and mixed myself a drink big enough to float a canoe. “Like the little guy who was told to wash his hands.”

“It’ll be all right with me if you talk when you’re spoken to,” he said, his face tight with rage.

Gorman said, “Don’t get excited, Dominic.”

The hoarse, scratchy voice had an effect on Parker. He sat down again and frowned at his fingernails. There was a pause. I lifted my glass, waved it at Gorman and drank. The Scotch was as good as the diamond.

“Is he going to do it?” Parker asked suddenly without looking up.

“Tomorrow night,” Gorman said. “Explain it to him. I’m going to bed.” He included me in the conversation by pointing a finger the size of a banana at me. “Mr. Parker will tell you all you want to know. Good night, Mr. Jackson.”

I said good-night.

At the door, he turned to look at me again.

“Please cooperate with Mr. Parker. He has my complete confidence. He understands what has to be done and what he tells you is an order from me.”

“Sure,” I said.

We listened to Gorman’s heavy tread as he climbed the stairs. The room seemed empty without him.

“Go ahead,” I said, dropping into one of the lounging chairs. “You have my complete confidence, too.”

“We won’t have any funny stuff, Jackson.” Parker was sitting up very stiff in his chair. His fists were clenched. “You’re being paid for this job and paid well. I don’t want any impertinence from you. Understand?”

“So far I’ve only received two hundred dollars,” I said, smiling at him. “If you don’t like me the way I am, send me home. The retainer will cover the time I’ve wasted coming out here. Suit yourself.”

A tap on the door saved his dignity. He said to come in, in his cold, spiteful voice, and thrust his clenched fists into his trouser pockets.

The chauffeur came in, carrying a tray. He had changed into a white drill jacket that was a shade too large for him. On the tray was a pile of sandwiches, cut thick.

I recognized him now that he wasn’t wearing the cap. I’d seen him working at the harbor. He was a dark, sad-looking little man with a hooked nose and sad, moist eyes. I wondered what he was doing here. I remembered seeing him painting a boat along the waterfront a few days ago. He must be as new to this job as I was. As he came in, he gave a quick look and a puzzled expression jumped into his eyes.

“What’s that supposed to be?” Parker snapped, pointing to the tray.

“Mr. Gorman ordered sandwiches, sir.”

Parker stood up, took the plate and stared at the sandwiches. He lifted one with a finicky finger and thumb, frowned at it in shocked disgust.

“Who do you think can eat stuff like this?” he demanded angrily. “Can’t you get into your gutter mind sandwiches should be cut thin—thin as paper, you stupid oaf. Cut some more!” With a quick flick of his wrist he shot the contents of the plate into the little guy’s face. Bread and chicken dripped over him, a piece of chicken lodged in his hair. He stood very still and went white.

Parker stalked to the French windows, wrenched back the curtains and stared out into the night. He kept his back turned until the chauffeur had cleared up the mess.

I said, “We don’t want anything to eat, bud. You needn’t come back.”

The chauffeur went out without looking at me. His back was stiff with rage.

Parker said over his shoulder, “I’ll trouble you not to give orders to my servants.”

“If you’re going to act like an hysterical old woman I’m going to bed. If you have anything to tell me, let’s have it. Only make up your mind.”

He came away from the French windows. Rage made him look old and ugly.

“I warned Gorman you’d be difficult,” he said, trying to control his voice. “I told him to leave you alone. A cheap crook like you is no use to anyone.”

I grinned at him.

“I’ve been hired to do a job and I’m going to do it. But I’m doing it my way, and I’m not taking a lot of bull from you. That goes for Fatso, too. If you want this job done, say so and get on with it.”

He struggled with his temper and then, to my surprise, calmed down.

“All right, Jackson,” he said mildly. “There’s no sense in quarrelling.”

I watched him walk stiff-legged to the sideboard, jerk open a drawer and take out a long roll of blue paper. He tossed it on the table.

“That’s the plan of Brett’s house. Look at it.”

I helped myself to another drink and one of his fat cigarettes I found in a box on the sideboard. Then I unrolled the paper and studied the plan. It was an architect’s blueprint. Parker leaned over the table and pointed out the way in, and where the safe was located.

“Two guards patrol the house,” he said. “They’re ex-policemen and quick on the trigger. There’s an elaborate system of burglar alarms, but they are only fixed to the windows and safe. I’ve arranged for you to enter by the back door. That’s it, here.” His long finger pointed on the plan. “You follow this passage, go up the stairs, along here to Brett’s study. The safe’s here, where I’ve marked it in red.”

“Hey, wait a minute,” I said sharply. “Gorman didn’t say anything about guards and alarms. How is it the Rux dame didn’t touch off the alarm?”

He was expecting that one, for he answered without hesitation. “When Brett returned the dagger to the safe he forgot to reset it.”

“Think it’s still unset?”

“It’s possible, but you mustn’t rely on it.”

“And the guards? How did she miss them?”

“They were in another wing of the house at the time.”

I wasn’t too happy about this. Ex-policemen guards can be tough.

“I have a key that’ll fit the back door,” he said casually. “You needn’t worry about that.”

“You have? You work fast, don’t you?”

He didn’t say anything to that.

I wandered over to the fireplace, leaned against the mantel.

“What happens if I’m caught?”

“We wouldn’t have chosen you for the job if we thought you’d be caught,” he said, and smiled through his teeth.

“That still doesn’t answer my question.”

He lifted his elegant shoulders. “You must tell the truth.”

“You mean about this babe walking in her sleep?”

“Certainly.”

“Persuading Redfern to believe a yarn like that should be fun.”

“If you are careful it won’t come to that.”

“I hope it doesn’t.” I finished my drink, rolled up the blueprint. “I’ll study this in bed. Anything else?”

“Do you carry a gun?”

“Sometimes.”

“You better not carry it tomorrow night.”

We studied each other.

“I won’t.”

“Then that’s all. We’ll go out tomorrow morning and look Brett’s place over. The lay of the land is important.”

“It strikes me it’d be easier to let that stripper do it in her sleep. According to Fatso, if she has anything on her mind she sleepwalks at the drop of a hat. I could give her something for her mind.”

“You’re being impertinent again.”

“So I am.” I collected a bottle of Scotch and a glass from the sideboard. “I’ll finish my supper in bed.”

“We don’t encourage people we hire to drink.” He was very distant and contemptuous again.

“I don’t need any encouragement. Where do I sleep?”

Once more he had to struggle with his temper, and went out of the room with a little flounce that told me how mad he was.

I followed him up the broad stairs, along a passage to a bedroom that smelled as if it had been shut up for a long time. Apart from the stuffy, stale air, there was nothing wrong with the room.

“Good night, Jackson,” he said curtly and went away.

I poured myself out a small Scotch, drank it, made another and walked to the window. I threw it open and leaned out. All I could see were treetops and darkness. The brilliant moonlight didn’t penetrate through the trees or shrubs. Below me I made out a flat roof, a projection over the bay windows that ran the width of the house. For something better to do I climbed out of the window and lowered myself onto the roof. At the far end of the projection I had a clear view of the big stretch of lawn. A lily pond that looked like a sheet of beaten silver in the moonlight held my attention. It was surrounded by a low wall. Someone was sitting on the wall. It looked like a girl, but I was too far away to be sure. I could make out a tiny spark of a burning cigarette. If it hadn’t been for the cigarette, I would have thought the figure was a statue, so still was it sitting. I watched for some time, but nothing happened. I went back the way I had come.

The chauffeur was sitting on my bed waiting for me as I climbed in through the window.

“Just getting some fresh air,” I said as I hooked my leg over the sill. I didn’t show I was startled. “Kind of stuffy in here, isn’t it?”

“Kind of,” he said, keeping his voice low. “I’ve seen you somewhere before, ain’t I?”

“Along the waterfront. Jackson’s the name.”

“The dick?”

I grinned. “That was a month ago. I’m not working that racket anymore.”

“Yeah, I heard about that. The cops picked on you, didn’t they?”

“The cops picked on me.” I found another glass, made two stiff drinks. “Want one?”

His hand shot out.

“Can’t stay long. They wouldn’t like me being up here.”

“Did you come for a drink?”

He shook his head. “Couldn’t place you. It sort of worried me. I heard the way you spoke to that heel Parker. I thought you and me might get together.”

“Yeah,” I said. “We might. What’s your name?”

“Max Otis.”

“Been working here long?”

“Started today.” He made it sound as if it was a day too long. “The dough’s all right, but they kick me around. I’m quitting at the end of the week.”

“Told them?”

“Not going to. I’ll just take it on the lam. Parker’s worse than Gorman. He’s always picking on me. You saw the way he behaved….”

“Yeah.” I hadn’t time to listen to his grievances. I wanted information.

“What do you do around here?”

His smile was bitter. “Everything. Cook, clean the house, run the car, look after that heel Parker’s clothes, buy groceries, the drinks. I don’t mind the job—it’s them.”

“How long have they been here?”

“Like I said—a day. I moved them in.”

“Furniture and all?”

“No…they’ve rented the place as it stands.”

“For how long?”

“Search me. I wouldn’t know. They only give me orders. They don’t tell me nothing.”

“Just the two of them?”

“And the girl.”

So there was a girl.

I finished my drink and made two more.

“Seen her?”

He nodded. “Rates high on looks, but keeps to herself. Calls herself Veda Rux. She likes Parker the way I do.”

“That her out in the garden by the pond?”

“Could be. She sits around all day.”

“Who gave you the job?”

“Parker. I ran into him downtown. He knew all about me. He said he’d been making enquiries and would I like to earn some solid money.” He scowled down at his glass. “I wouldn’t have touched it if I’d known the kind of rat he is. If it wasn’t for the gun he carries, I’d take a poke at him.”

“So he carries a gun?”

“Holster job, under his left arm. He carries it as if he could use it.”

“These two guys in business?”

“Don’t seem to be, but your guess is as good as mine. No one’s called or written. No one telephones. They seem to be waiting for something to happen.”

I grinned. Something was going to happen all right.

“Okay, pally, you shoot off to bed. Keep your ears open. We might learn something if we’re smart.”

“Don’t you know anything? What are you here for? What’s cooking? I don’t like any of this. I want to know where I stand.”

“I’ll tell you something. This Rux frail walks in her sleep.”

He looked startled. “You mean that?”

“That’s why I’m here. And another thing, she takes off her clothes at the drop of a hat.”

He chewed this over. He seemed to like it. “I thought there was something different about her,” he said.

“Play safe and take your hat to bed with you,” I said, easing him to the door. “You might be in luck.”

CHAPTER THREE

IT WASN’T UNTIL THE following afternoon that I met Veda Rux.

In the morning, Parker and I drove over in the Packard to Brett’s house. We went around the back of the foothills and up the twisting mountain road to the summit where Ocean Rise has its swaggering terminus.

Parker drove. He took the bends in the mountain road too fast for comfort, and twice the car skidded and the rear wheels came unpleasantly near to the edge of the overhang. I didn’t say anything; if he could stand it, I could. He drove disdainfully, his fingertips resting on the steering wheel as if he were afraid of getting them soiled.

Long before you reached it, you could see Brett’s house. Although surrounded by twelve-foot walls, the house itself was built on high ground and you could get a good view of it from the mountain road. But when you reached the gates the screen of trees, flowering shrubs and hedges hid it from sight. Halfway up the road, Parker stopped the car so I could get an idea of the layout. We had brought the blueprint with us, and he showed me where the back door was in relation to the house and the plan. It meant scaling the wall, he told me, but as he hadn’t to do it, he didn’t seem to think that would be anything to worry about. There was a barbed-wire fence on the top of the wall, he added, but that, too, was something that could be taken care of. He was a lot happier than I was about the setup. But that was natural. I was doing the job.

There was a guard standing before the big iron gates. He was nearly fifty, but looked tough, and his hard, alert eyes held us as we pulled up where the road petered out about fifty yards beyond the gates.

Parker said, “I’ll talk to him. Leave him to me.”

The guard strolled toward us as Parker made a U-turn. He was short and thickset, with shoulders on him like a prizefighter’s. He had on a brown shirt, brown corduroy breeches and a peaked cap, and his short thick legs were encased in jackboots.

“I thought this was the road to Santa Medina,” Parker said, poking his slick head out of the car window.

The guard rested one polished boot on the running board. He stared hard at Parker, then at me. If I hadn’t been told he was an ex-cop, I would have known it by the sneering toughness in his eyes.

“This is a private road,” he said with elaborate sarcasm. “It says so a half a mile back. The Santa Medina road branches to the left, and there’s a notice four yards square telling you just that little thing. What do you want up here?”

While he was shooting off his mouth, I had time to study the walls. They were as smooth as glass, and on top was a three-stranded barbed-wire fence. The prickles on the wire looked sharp enough to slice meat—my meat at that.

“I thought the road to the left was the private road,” Parker was saying. He smiled emptily at the guard. “Sorry if we’re trespassing.”

I saw something else, too: a dog sitting by the guard’s lodge—a wolfhound. It was yawning in the sunlight. You could hang a hat on its fangs.

“Beat it,” the guard said. “When you’ve got the time, learn yourself to read. You’re missing a lot.”

Around the guard’s thick waist was a revolver belt. There was no flap to the holster and the butt of the .45 was shiny with use.

“You don’t have to be impertinent,” Parker returned gently. He was still very distant and polite. “We all make mistakes.”

“Yeah, your mother made a beauty,” the guard said and laughed.

Parker flushed pink.

“That’s an objectionable remark,” he said sharply. “I’ll complain to your employer.”

“Scram,” the guard said, growling. “Take this lump of iron the hell out of here or I’ll give you something to complain about.”