Полная версия

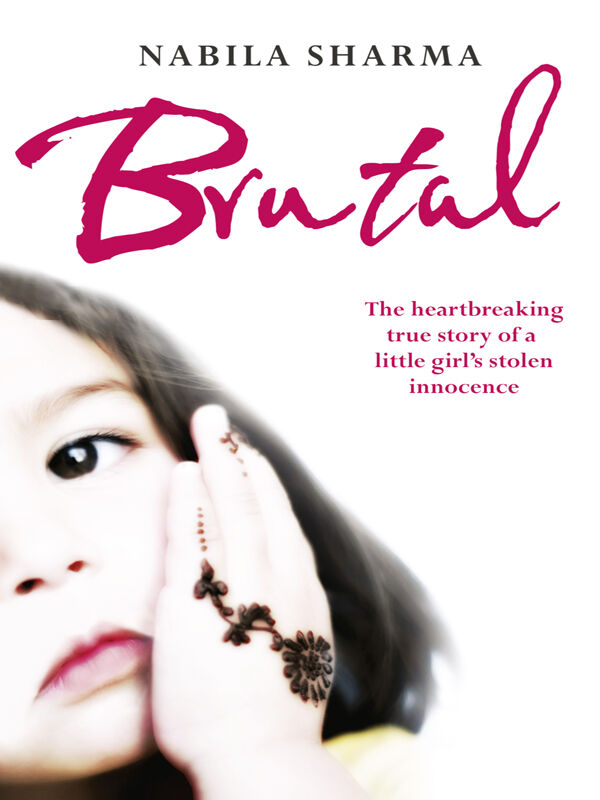

Brutal: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Little Girl’s Stolen Innocence

Nabila Sharma

Brutal

The Heartbreaking True Story of a Little Girl’s Stolen Innocence

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Prologue

1 The Girl with Ribbons in Her Hair

2 Living on Sikh Street

3 The Wolf, the Witch and the Wallpaper

4 The Mosque

5 Arrival of the New Imam

6 The Imam’s Secret Handshake

7 The Chosen One

8 Secret Lessons

9 The Imam’s Bite

10 Treasure under the Carpet

11 The Trip to the Petrol Station

12 A Lost Innocence

13 The Trip to London

14 The Sickly Boy

15 Washing Away My Shame

16 The Protector

17 Self-harm and Scourers

18 Saying ‘No’

19 The Special Dinner

20 The Card in the Kitchen

21 Being Found Out

22 An Arranged Future

23 Rebellion

24 My Sikh Boyfriend

25 New Beginnings

26 Starting Again

Acknowledgements

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

I’m running around the garden in the sunshine. My brother turns to throw a red rubber ball towards me and I watch as it sails high up into the air. I stretch up my hands to try and catch it and, as I do, the sunshine blinks between my fingertips. It’s a hot day and I can feel the sun baking my skin.

My dolls are sitting in a neat line in their pram. I’ve brushed their long glossy hair and dressed them in nice clothes and they look beautiful. Their hair isn’t as long as mine, though. Mine stretches below my bottom and attracts comment wherever I go. ‘Isn’t she lovely?’ they say. ‘What a beauty!’

Maybe that’s why the new imam at the mosque singles me out from the start. ‘You’re a pretty one,’ he says, and asks me to help with the cleaning. I feel very proud. He’s a strange-looking man, with his freckles and protruding belly and the funny sarong he wears, but he’s the imam, the leader of our community, the one all the parents want to impress. The other girls are jealous of the attention he pays me.

Every evening after school I go to the mosque for lessons with seventy other children. We all line up to shake the imam’s hand and say ‘Salaam alaikum’, to which he replies ‘Alaikum salaam’. But one night as he holds my hand, he does something odd. He strokes the inside of my palm with his index finger, wiggling it around, tickling me. I’m confused. Should I do the same thing back? Then he jabs his finger hard into my hand, as if to make a point.

I watch carefully as he shakes hands with the other children and I don’t think he does the funny handshake with them.

It’s on my mind as I play in the garden. Why me? There are times when I’m not sure what to make of it. I’m only seven. I feel like I’ve been chosen for something. But I don’t know what.

Chapter 1

The Girl with Ribbons in Her Hair

I slipped on my shoes without stopping to fasten them, opened the back door and shot straight out into the back garden. My brother Asif was holding my favourite doll by the hair, swinging her round like a helicopter.

‘I’ll get you!’ I shouted crossly, waving my tiny fist in the air.

The shoes slopped off my heels with every step I took, slowing me down.

‘Give me my doll!’ I demanded as I tried to catch him.

‘Nope,’ Asif teased.

‘Give her back now or … or …’ I couldn’t think of a strong-enough threat.

‘Or what?’ he challenged.

‘I’ll tell Mum.’

‘Oooh, I’m really scared,’ Asif laughed. The doll spun faster and faster around his head, her arms and legs splayed out. She was already naked and muddy from being kicked around the garden.

With all my might I stretched up on tiptoes to try and grab her, but it was no good. Asif was much taller than me. I hated my brothers. They were mean to me. Why didn’t I have a sister instead?

I rubbed my eyes and began to sob.

‘Anyway, it’s only a stupid doll,’ Asif teased, knotting her hair between his fingers. He was eight years old to my five, and an expert at winding me up.

The sky had clouded over and it began to rain. I felt utterly miserable as the drizzle fell on my upturned face.

‘Nabila!’ Mum’s voice called suddenly from the back door.

Asif froze. Had Mum spotted him tormenting me from the back window? He dropped the doll guiltily on the ground and took a giant step away.

I seized the moment and, scooping her into the safety of my arms, surveyed the damage. Her ice-blonde hair was knotted and ratty and her face was caked in mud. With the sleeve of my dress I wiped a big dollop of mud from her forehead.

‘There, that’s better, isn’t it?’ I soothed, rocking her in my arms.

Asif was still watching the back door to see if Mum was about to come storming out, so I grabbed my chance and gave him a swift kick on the leg.

‘Oww,’ he groaned, rubbing his shin bone.

‘Nabila!’ Mum called again, her voice impatient. ‘Come in now. I need to do your hair!’

I rolled my eyes skywards and called, ‘Okay, coming!’

Asif’s face broke into a sarcastic smile. ‘Go on then, pretty little girl,’ he teased in a whiny voice. ‘Hurry up and get some greasy oil in your stupid hair!’

I stuck my tongue out at him, and hurried inside to where Mum was waiting.

The room was too hot. She had the gas fire on full blast and the flames flickered from yellow to blue. I thought how pretty they looked as they danced across the front of the fire.

The room smelled of coconuts. Mum had melted some coconut oil in a little silver bowl balanced on top of the gas fire. She swore by it because she’d heard that it made your hair thick and strong but, more importantly, that it made it grow even faster. Mum was obsessed with my hair.

‘It’s your crowning glory, Nabila,’ she insisted. ‘You must look after it.’

I hadn’t had my hair cut since the day I was born and by the time I was five it hung down below my bottom. When I sat on the floor the ends would flick out along the carpet like black spiders’ legs trying to crawl away from me. Every day Mum would oil and plait my hair in front of the fire. I hated it because it always took ages, and when she pulled too hard it hurt. Sometimes it felt as if she was sticking a thousand pins into my scalp as she tugged and plaited it all with ribbons.

Everyone noticed my hair, and the comments were usually admiring – but not always. One day, I was walking down the street holding Mum’s hand when a lady passed us. As soon as she saw the plaits swishing around my bum, she stopped and did a double-take.

‘It’s cruel letting a child wear her hair so long!’ she exclaimed to Mum. ‘It must be so much work.’

Mum just stuck her nose in the air as if she didn’t care. I don’t know what the woman’s problem was. I loved the fact my hair was so long I could sit on it. It made me feel special, like Rapunzel.

It wasn’t just my hair Mum fussed over; she also made all my clothes herself. She shopped around for different fabrics and ran them up into outfits on her little sewing machine. I had tops and trousers in every colour of the rainbow. My favourite dress was a sunshine yellow one with a zig-zag red trim along the bottom of the hem. It was bright and beautiful.

Whenever she did my hair Mum would be sure to match the colour of the ribbon with the outfit I was wearing. She threaded the ribbons inside my plaits and the colour streaked through, making them look even longer.

Dad said that the reason why Mum dressed me like a doll was because she’d waited so long for a little girl. When I was finally born, she couldn’t believe it. She had almost died during the pregnancy. She’d been working in our family’s shop when she began to feel really ill and collapsed. Dad called for the doctor, who diagnosed tuberculosis – a horrible word that stuck in my head. The GP warned them that even if the baby was born alive, it would be horribly deformed.

In fact, the doctor was so convinced of this that he insisted on being present at my birth, ready to comfort my parents when they saw me. But against all odds I arrived perfectly healthy and with a full head of black hair!

Dad was so delighted that he jumped around the room with joy. Mum just sat and wept quietly.

‘Why was she sad?’ I asked.

Dad shook his head. ‘Not sad, Nabila. She cried because she was so happy. You were all she ever wanted.’

He explained that he’d chosen the name Nabila as soon as the midwife placed me in his arms. ‘We chose it because it means happiness, and after your four brothers your mum was happy to finally have her little girl.’

He told me that I’d had a fifth brother called Aaban, but he’d died when he was only six hours old. His lungs weren’t strong enough to breathe outside Mummy’s tummy. My parents held his tiny hand and cried whilst they watched his life ebb away. Dad said losing Aaban broke Mum’s heart, but that I’d mended it.

‘That’s why you are so precious to us. You mean the world to us,’ he said, kissing me tenderly on my forehead.

My father’s family had rescued Mum from a horrible life as an orphan back in Pakistan. Her mother had died when she was three years old, then her dad died when she was seven. My mother, whose name was Shazia, her brother Sawad, then aged twelve, and her nine-year-old sister were split up and farmed out to different relatives. Mum was taken in by her grandmother but the family were cruel and treated her like a slave. My dad’s mother, who lived close by, realised what was going on and took Shazia in and gave her shelter, then my dad, Mohammed, the eldest son of the family, decided to marry her when he was twenty-eight and she was just thirteen years old. I loved hearing the story of how my parents met. I imagined Dad as a dashing prince, saving Mum from her wicked relatives.

Dad decided to move to England to make a better life for his family. He told me he’d driven all the way to Britain from Pakistan in his car.

‘I did it for me, your mum – all of us.’

He only stopped driving when he needed to sleep, except from time to time he had to stop and do some work so that he could afford another tankful of petrol.

I shut my eyes and tried to imagine my dad driving across the desert in his battered old car, like Lawrence of Arabia. It all seemed very exciting.

It took him almost six months to make the journey but he finally arrived in England at the beginning of the 1960s.

‘Things were very different then,’ he told me, his eyes widening at the memory. ‘Women wore these very short skirts, and men – well, they wore their hair really long, like girls!’

I pulled at my own hair. ‘What, like mine?’

‘No, not as long as yours, but too long for a man. I’d never seen anything like it!’

Eventually, when he’d saved up enough money, Dad bought a shop in the Midlands, a typical grocery store with a butcher’s shop at the back. He could turn his hand to most things, but he was a particularly skilled butcher.

Mum gave birth to my eldest brother Habib in 1968; he was followed by Saeed, Tariq and Asif, then I came along in 1976.

Habib was a typical eldest brother, eight years older than me but it might as well have been twenty. He was bossy and always telling me what to do. I hated Habib. He was moody and mean. He resented being the oldest because it meant he had to help more around the house and, in particular, he was often told to babysit for the rest of us.

Each night, Mum would chop and prepare all the food in the flat above the shop. We spent most of our time up there as youngsters, while Mum and Dad were working downstairs. At mealtimes, Habib had to turn on the cooker and heat up the food Mum had prepared earlier. It was his job to feed us.

‘You should be the one cooking,’ he complained to me. ‘You’re the girl, not me. This is a girl’s job.’

That’s how Habib was. He was clever and he knew it, but he also thought he was too important to look after the rest of us.

My second-eldest brother Saeed was a year younger than Habib, but he wasn’t as smart. Saeed was good with his hands. He loved taking things apart just to see how they worked. One day he took one of my dolls to bits. First he pulled her head off and then her arms and legs until there was nothing left apart from a stumpy body. He tried to put her back together again but it didn’t work so she remained an amputee.

He did this with all our toys and his own as well, which made my parents despair. When we were older and got bikes of our own we didn’t dare leave them in the garden in case Saeed got his hands on them.

Tariq was the tough one, a typical boy, who used to beat me up all the time. He loved to fight and nothing or no one would ever be able to hurt him back. He was mad on wrestling and boxing and used me as his very own punchbag.

‘Just stand there while I hit you,’ he instructed.

‘But I don’t want to be hit. You’ll hurt me!’

‘I need to practise my moves and if you don’t stand still I’ll hurt you more.’

Seconds later I was lying in a crumpled heap on the floor, with Tariq standing over me.

‘Get up, Nabila. I need to do it again.’

Sometimes he was so rough that he crossed the line and our so-called ‘play fighting’ became something more akin to torture, with me as the unwilling victim.

Asif was my youngest brother, and although he teased me constantly he was also the kindest one. There were only three years between us so we often played together, which annoyed Habib no end. He teased Asif for playing with a girl, but secretly I think he was jealous of our friendship because no one liked Habib.

I adored Asif. He was my favourite brother, and even if he teased me he always stuck up for me if need be. We spent lots of time together, making up games. My favourite was one in which Asif pushed me round the garden in my dolls’ pram, like a baby. We’d giggle away until we felt sick.

As we grew older, though, Asif began to spend less and less time with me. He discovered football, his head was turned and he was off, leaving me far behind.

Our house was just a few streets away from my parents’ shop. We’d moved there not long after I was born so that we’d have more room, but it was still small and cramped inside. There were three bedrooms upstairs but one was used as a storage room and was constantly piled high with boxes of stock from the shop. My parents slept in the second bedroom and my brothers shared the third. The boys had the biggest room, but with four of them sleeping in two double beds they needed it.

I slept in a little bed in my parents’ bedroom. My dad worked in the shop by day and had a job as a labourer at night to supplement his income. They were building a new shopping centre on the other side of town and Dad was paid to drive a big bulldozer. It was his job to dig out all the soil so that building work could begin. It meant he got hardly any sleep, just sneaking a nap here and there when the shop was quiet.

Even though he was exhausted, Dad would always spend at least quarter of an hour playing with me when he got home from his night shift. I’d roll about on the floor as he tickled my tummy and sometimes I’d giggle so much I’d feel sick. Then he would scoop me up in his big strong arms for a cuddle and call me ‘Baby’. It was his nickname for me because I was the baby of the family – his baby girl.

With Dad away at work most nights, I’d sneak into their double bed and snuggle up to Mum. I’d curl in tight, wrapping my arms around her waist and absorbing the heat from her sleeping body. It made me feel warm and safe to be next to her, although I was always closer to Dad when he was there. I was a real daddy’s girl.

Maybe one reason I wasn’t closer to Mum was that her English wasn’t very good when I was small. She spoke to us in a mixture of her native Urdu and pidgin English, and while I understood most of what she said, I spoke only a few words of Urdu myself. Sometimes her lack of English made her struggle when she was serving in the shop so when I was five Dad suggested that she enrol in a night class at my infant school and learn the language properly. She improved a lot after that and would practise in front of customers, but if she went wrong or was lost for the right word, she’d call to Dad or one of my brothers for help.

Our grocery store sold staples like milk, bread, cigarettes and canned goods, as well as meat. We never stocked fruit and veg. I think Dad had an arrangement with the greengrocer next door that we wouldn’t encroach on his trade.

I loved the fact that my parents ran their own shop because of the extra perks. When Mum and Dad weren’t looking, my brothers would make me sneak downstairs and steal sweets from the front counter. One afternoon, just after locking-up time, we were in the rooms above the shop when Tariq told me I had to go and get some chocolate bars.

‘Go on,’ he hissed, giving me a jab in the ribs.

My heart was in my mouth as I crept silently downstairs, being careful to avoid the second-bottom step because it always creaked if you stood on it. At that moment I heard a noise above me and froze in my tracks. It was the sound of the toilet being flushed. Dad must be in there. I waited until I heard his heavy footsteps move into the living room. My heart pounded in my chest as I tiptoed over to the counter and grabbed as many chocolate bars as I could. I pulled up my trouser legs and wedged four or five bars in the top of each sock. With that I sneaked back upstairs, walking with difficulty. When I finally made it back to the room I was welcomed as a hero.

‘Brilliant! What did you get?’ Saeed said, grabbing at my leg.

‘Wait a minute,’ I said, slapping his hands away. ‘Let me get them out first.’

‘Yuck, I’m not eating them. They’ve been near her smelly feet.’ Tariq stuck his fingers down his throat in a gagging motion.

‘Fine, I’ll have yours then!’ Asif said, quick as a flash.

‘Sssh,’ Saeed whispered dramatically, putting his finger to his lips. ‘Habib will hear, and if he does we’ll all be for it.’

Habib was supposed to be looking after us and he’d have got into trouble if I’d been caught. Tariq and Asif shared the chocolates between them and all they gave me for my trouble was a Curly Wurly, but at least I’d earned their respect. Maybe having a little sister wasn’t so bad after all.

This became a regular occurrence and I’m sure that after a while Mum and Dad must have sussed out what we were up to, but nothing was ever said.

The butcher’s area at the back of our shop was always a hive of activity. Dad would take delivery of halal meat from the local slaughterhouse and I’d watch with morbid fascination as he chopped off animals’ wings and limbs using special meat cleavers and razor-sharp knives. The sound of metal hitting the wooden chopping block used to make me jump. What wasn’t chopped up was minced, using a large stainless-steel mincing machine. Dad’s meat cuts were legendary and people would queue from early in the morning to buy the best joints.

At night, he’d wearily pull down the shutter at the front of the shop and head for his second job on the building site. I’d usually only see him in the morning, when I got up for school, and he would just be getting in from work, ready to wash and start all over again in the shop.

Soon, the toll of having two jobs began to wear him out so he called his brother Kahil over from Pakistan to help in the butchers’. Mum would work in the grocery, while Uncle Kahil served and prepared meats in the back with Dad. It gave my father more time to rest and it also gave Kahil a better life. Like my father, Kahil settled in England. He married a girl over in Pakistan and brought his wife back to England. Soon, they’d bought a house and begun to raise a family of their own.

With the extra pair of hands Dad was able to get some rest in the mornings, but he’d have to be there by midday to cope with the lunchtime rush so he still only had a few hours’ sleep. He worked five nights a week at the building site and seven days a week at the shop.

At home, my four brothers would constantly bicker and fight. Mum was usually ratty and exhausted. She’d shout out orders in Urdu and deliver slaps here and there as she tried to bring some kind of order to the household, but it never worked and that made her even more short-tempered.

On the other hand, our father never raised his voice to us. He didn’t have to, because one look from him was enough to quieten even the fiercest argument. His kids were his life but he couldn’t stand confrontation and discord. He was a peaceful, hard-working man, who took pleasure in watching his children grow and develop. The last thing he wanted after all the hours he worked was to come home to any kind of trouble.

I enjoyed looking pretty and liked all the nice clothes Mum made me, but my looks separated me from my brothers. It stopped me joining in their games, because they saw me as some stupid girly girl.

‘Where are you going?’ I asked Habib one day, as I watched him retrieve a bat and ball from a cupboard underneath the stairs.

‘To the park to play cricket,’ he snapped, his tone implying it was none of my business.

I screwed up my nose, annoyed that no one had asked me.

‘Please can I come?’ I asked politely.

‘Girls can’t play cricket,’ he answered crossly.

I was furious and wouldn’t let it go. When Mum heard us arguing, she left the pot of steaming hot curry cooking in the kitchen to come out to the hall and intervene.

‘Habib, take your sister with you and look after her. If she wants to play cricket, let her join in!’ she scolded in Urdu, no doubt seeing a chance to get us kids out from under her feet for a few hours.

Habib’s face changed. A mood descended on him like a black cloud. Reluctantly he agreed to take me, but he flashed me a filthy look. Having his little sister in tow, trailing behind him, slowing him down, would mess up his plans for the rest of the day. With my back to my mother, I stuck out my tongue at him – but my triumph didn’t last long.

As soon as we arrived at the local park I was dispatched to the far reaches of the grounds. It was a baking hot day and the grass was dry and itchy under my feet.

‘Stand there and catch the ball if it comes your way,’ Habib instructed me.

I stood where I was told and my four brothers disappeared into the distance. I could just about make out that the game was in progress but I was further removed from it than a spectator in a back row seat at Lords cricket ground.

‘Hey, when’s it going to be my turn?’ I hollered, as I stood hot and uncomfortable in the sweltering heat, my brown leather sandals too tight on my feet.

‘When we tell you,’ Habib yelled back.

Soon the light began to fade and I still hadn’t had a turn. I wasn’t wanted or needed there. Instead I stood, lonely and left out, like a spare part waiting to be collected on the way home. I learned my lesson that day. If I wasn’t invited, it was because my four brothers didn’t want their little sister joining in. My place was to be pretty, the shining trophy of the family. It was no use trying to be one of the boys. I was the little girl with the ribbons in her hair, and that’s all I was good for.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.