Полная версия

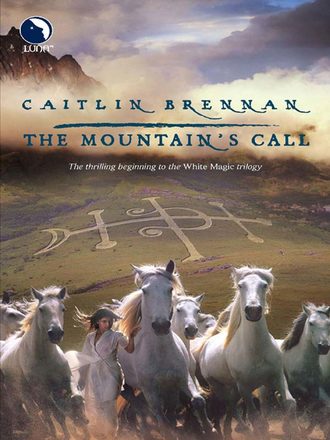

The Mountain's Call

The boy from Mallia had his own small tent, which was pitched every night beside the caravan master’s. One of the master’s servants saw to his needs. He ate his meals with the master or his guards. He was kept as close as a virgin daughter.

Euan loved a challenge. He scouted the ground and laid his plan. By the second day he was ready to make his move.

The night before, they had stayed in one of the imperial caravanserais. Tonight they were too far from the nearest town to cover the distance before dark. They camped along the road instead, setting up a guarded camp with earthen walls in the legionary style.

While most of the guards were busy with the earthwork, Euan saw his opening. The boy insisted on taking care of his own horse, against some opposition. Euan chose to station his horse in the line not far from the black, and to practice his newly acquired horse-tending skills.

The boy was much better at it than he was. He hardly needed to pretend to be inept. As he had hoped, his fumbling brought the boy over to lend a hand.

This was not a boy. Euan was sure of that as they worked side by side to rub the horse down and feed him his nose bag of barley. It was like a fragrance so faint he was barely aware of it. This was a young woman.

Once Euan had assured himself of that, he could not see her as a man. Her hands were too slender and her throat too smooth. Her face was too fine to be male, even young imperial male.

He kept his thoughts to himself and stood with her while the horse ate his barley, watching the last of the earthwork go up around them. “You build a city in an hour,” he said. “Then in the morning, in much less than an hour, the wall will be gone and the camp with it. It’s a very imperial thing. Even for a night you raise up a fortress.”

She slanted a glance at him. Her eyes were a fascinating color, not exactly brown, not exactly green, with flecks of gold like sunlight in a forest pool. “You speak Aurelian well,” she said.

“I work at it.”

“The way you work at your riding?”

He snorted. “We’re not born on a horse’s back and suckled on mares’ milk the way you people are.” He paused. “Am I really that bad?”

“The others are worse.”

“Probably not by much.”

The corner of her mouth turned up. “You could almost learn to ride.”

“I hope so,” he said. “That’s what we’re doing. We’re going to the Mountain, to the School of War. We’re supposed to learn to be cavalrymen.”

“I suppose if anyone can teach you, the masters there can.”

“So everyone hopes,” Euan said. He paused before he cast the dice. “My name is Euan. And yours?”

“Valens,” she said.

That was a man’s name. Euan was careful not to comment on it. “I take it you’re for the Mountain, too. School of War?”

“I’m Called,” she said.

She spoke as if he must know what she was talking about. It took him a while to understand, then to realize what, in this case, it meant. He almost said, “But surely women aren’t—”

He caught himself just in time. This was beyond interesting. It was a gift from the One God.

He would have to play it very, very carefully. He bent his head in respect, as he had heard one should, and let her see a little of his fascination. “You’re the first I’ve seen,” he said. “No wonder they’re transporting you with the treasure.”

Her lip curled. “That’s not because I’m Called. It’s because of Kerrec.”

She spoke the name as if it had a bitter taste. She had not forgiven the man for abandoning her to the caravan. That too Euan could use.

He put on an expression of wry sympathy. “Your brother?” he asked.

“Not in this life,” she said.

Ah, so, he thought. “He’s too protective, is he? Or not protective enough?”

“He’s too everything,” she said. She spun on her heel. “I’m hungry. They always feed me too much. Would you help me with it?”

“Gladly,” he said, and he meant it.

Once more her mouth curved in that enchanting half-smile. “I’ve seen what they’ve been feeding you,” she said. “You shouldn’t have to be eating soldier’s rations here.”

He shrugged. “They don’t love us. We’ve killed too many of them—won too many battles, too, even if we lost the war. We can hardly blame them for taking what revenge they can.”

“You have a great deal of forbearance,” she said. She sounded a little surprised. “I had always thought—”

He showed her all his teeth. “Oh, we’re wild enough. We take heads. We eat the hearts of heroes. That doesn’t stop us from understanding how an enemy thinks.”

“Of course not,” she said. “The better you understand, the easier it is to find ways to defeat him.”

Euan’s heart stopped. The Called were mages. He had let himself forget that quite important fact. Many mages could read patterns and predict outcomes. Mages of the Mountain could do more than that. Even one who was completely untrained and untested might be able to see too clearly for comfort.

He shook off his sudden fit of the horrors. It was a lucky shot, that was all. She showed no sign of denouncing him as a traitor to the empire.

Her dinner was certainly better than the one his kinsmen would be getting. He was not fond of the spices these people poured on everything, but the bread was fresh and good. There was meat, which he had not had in days, and it was not too badly overcooked. She left him most of that. He left her all of the greens and the boiled vegetables. “Horse feed,” he said.

That half smile of hers was a lethal weapon, if she wanted to use it that way. “I do want to be a horse mage, after all,” she said.

He saluted her with a half-gnawed bone. “I hope a cavalryman is allowed to eat like a man, then, instead of a horse.”

“You eat like a wolf,” she said. “They must be feeding you even worse than I thought.”

“It’s not what we’re used to,” he admitted.

She nodded as if in thought. There was a line between her brows. When she spoke again, it was to change the subject. “Tell me about your country.”

“In the south and west we have forests like yours,” he said. “Beyond that, past the spine of mountains, it’s a broad land of heath and crag. Rivers run there, too fast and deep to ford, and cold as snow. The wind cuts like a knife and sings like a woman keening for her lover. The bones of the earth are bare as often as not. It’s a hard country, but it raises strong men.”

“My father said there are fish in the lakes there that are as big as a man, with flesh so sweet that the gods could dine on it.”

“Your father has been there?”

“He fought there,” she said. “Does that bother you?”

“No,” he said. “War is life. A man is only a man if he’s fought well. I suppose your father did if he was in the legions. Which was his? The Valeria?”

She started as if he had stung her. Aha, he thought. So that was her proper name. She recovered quickly. “Yes. Yes, that was his legion.”

“We call them the Red Wolves,” he said. “Mothers terrify their children with the threat of them. They’re the great enemy. It was the Valeria that took us in the last battle and brought us into the empire.”

“You don’t hate them,” she said. “I’d think you would.”

“They’re a worthy opponent,” he said. “War has its balance. Someday we’ll defeat them and lead them in halters through our camps.”

“You are different than anything I expected,” she said slowly.

“Is that a good thing?” he asked.

It took her a moment to answer. “I’m not sure,” she said. “I’ll think about it.”

Euan thought he might be in love. This was not his first imperial woman, by far, but it was certainly the first who had wanted everyone to think she was a man. He would have liked to see her hair before she chopped it off. He would have liked even more to see what she was like under the sexless clothes she wore.

He was sure it was love when he came back to the rest of the hostages and found them lying back, replete after a feast identical to the one he had just finished. Someone had put in a word, it seemed. He could guess who it was.

They were all in her debt, and Euan made sure they knew it. He did not tell them her secret. If they had eyes to see, then they could. Otherwise, he would enjoy the field without a rival.

Chapter Four

The dark man’s name was Kerrec. He never actually told Valeria that himself. She heard it from the commander in Mallia.

That was her first grievance. By the time he packed her off with the caravan, she had a dozen more. He seemed determined to keep her from being grateful for her rescue, and equally determined to make her dislike him intensely. He was cold, arrogant, secretive, and intolerably condescending, and he had not a speck of charm.

The worst of it was, she could not hate him. She could never hate anyone who sat a horse like that.

Only one other thing almost persuaded her not to despise him. He had told the commander in Mallia nothing of her sex, only that she had been assaulted by the infamous pack of lordlings that had been preying on travelers and the odd local. The commander, like everyone else who heard the story, had been delighted with its ending, and more than pleased to grant her whatever she needed, horse and clothes and provisions and all.

Kerrec had not betrayed her to the caravan master, either. Both the caravan master and the commander had deduced on their own that she was Called, and treated her accordingly. Whether intentionally or because he simply did not care, Kerrec had done a great deal to help her on her way.

She found his perfect opposite in the barbarian prince who rode with the caravan. She had seen sacks of meal that rode better, but he did try, especially after she offered a suggestion or two. He was the biggest man she had ever seen, though not the broadest. He was still young and a little rangy, with long legs and big square hands. His hair was as red as copper.

There was a great deal of it. He wore it in thick braids to his waist. His cheeks and chin were shaven, but he cultivated thick red mustaches. His eyes were amber and tilted upward above high cheekbones, like a wolf’s. They had a wolf’s wicked intelligence, and a spark of laughter that never quite went away.

He loved to talk. His command of Aurelian was less than perfect, but he never let that stop him. She learned a fair bit of his language that way, and taught him a fair number of new words in Aurelian.

He had all the warmth and charm that Kerrec lacked. She reminded herself frequently that he was an enemy, but she was not about to let that stop her from enjoying his company.

She decided, by the third day out from Mallia, to forget the man who had rescued her from the hunt. She was unlikely ever to see him again. She made herself useful to the caravan, helping with the horses and lending a hand wherever else seemed appropriate. Her dreams were still as likely as not to have Kerrec in them, but she could turn her back on those.

Five days out from Mallia, while the caravan prepared to cross a bridge over a deep gorge with a river rushing far below, two young men rode up behind them. One was riding a sturdy brown mule, and was a sturdy brown person himself. The other rode bareback on a horse as delicate as a gazelle. His clothes were worn to rags, but they looked as if they had been rich when they were new. Traces of embroidery still lingered at the neck and hem of the long loose robe. His mare’s bridle swung with wayworn tassels. Her bit was tarnished silver.

The rider was as slim and fine-boned as the mare. His cheekbones were tattooed with blue swirls. In the center of his forehead was a complicated pattern of circles within circles in red and black and green.

Valeria had felt the two riders behind her since the night before. They were hunting, and their quarry was the same as hers. Even before she saw their faces, she knew that they were Called.

The brown man’s name was Dacius. He came from a town south of Aurelia. The other, Iliya, was from much farther away. He was a prince of Gebu in the land of spices. “A year and a day have I journeyed,” he said in his lilting Aurelian, “coming to the Mountain’s Call.”

He was a singer as well as a prince. Dacius was a tenant farmer from a noble’s estate. They had nothing in common but the Call, but that was enough.

Iliya was even more in love with the sound of his own voice than Euan was. Dacius was a listener. He had a quiet way about him that horses loved. The mule adored him, which was strikingly out of character for her hybrid species.

The caravan took them in. “Three of you at once,” the master said in deep satisfaction. “That’s more luck than we’ve had in a handful of years.”

Iliya’s smile was wide and white in his dark face. It was Dacius, rather surprisingly, who said, “That’s good, sir. We’re fair to middling useless otherwise, except as hostlers. It will be a good long time before we have any skills worth conjuring with.”

“You carry the luck,” the master said, “three times three. The gods are kind to us this season.”

Dacius shrugged. Iliya laughed. Valeria said nothing.

Everyone expected them to ride together. Iliya’s prattle covered the others’ silence. When he broke out in song, he insisted that everyone sing with him. It was a tuneful road that day, up from the bridge by a steep road with numerous switchbacks to a high plateau. They camped there on the windy level.

As usual, Valeria helped look after the horses. Iliya was busy entertaining the guards with songs and stories. Dacius helped with the earthwork that would protect the camp overnight. Even when she could not see them, she could feel them. They were like parts of her that had gone missing and come wandering back.

Euan had been keeping his distance since the riders came to the caravan. After the horses were settled, she found him tending a spit on which turned the carcass of a deer. One of his fellow hostages had shot it that morning with a bow that he had borrowed from a caravan guard. There had been a great to-do when the emperor’s guards realized what he had in his hand, which had taken all of Master Rowan’s skill to settle.

Now at evening the hostages were playing some game nearby that involved a set of knucklebones and a fair amount of either guffawing or snarling depending on how the bones fell. “Not in the mood to play tonight?” she asked Euan.

He started and spun. For an instant she saw a wolf at bay, with yellow eyes glittering and teeth bared. Then he was Euan again. “By the One God!” he said. “You scared me half out of my skin.”

“I’m sorry,” she said without too much repentance. “Why are you sulking? Is it too much for you to share a caravan with another prince?”

“I am not sulking,” he said sullenly.

“Then what are you doing?”

“Being jealous,” he said. “Those are your own kind. It’s like seeing horses in a herd.”

“They are my kind,” she admitted, “but it doesn’t feel like a herd at all. It feels strange. It makes me itch inside my skin.”

“Really?” He had brightened considerably. “You don’t want to abandon the rest of us?”

“Gods, no,” she said.

It was like standing in front of a fire to feel the warmth coming off him. He sighed deeply. “Good,” he said. “That’s good.”

The caravan inched its way through a tumbled landscape of ravine and forest. The towns they passed grew smaller and smaller until they dwindled away altogether. They could not see past the next hilltop. Whenever the trees opened or they reached the summit of a hill, the world was shrouded in mist and rain. Even when it was not raining, the clouds hung so low that they seemed to brush the tops of the trees.

In that perpetual damp and fog, Iliya wilted visibly. His cheerful babble stopped and his singing died away. Valeria had found it annoying while it went on, but once it stopped, she missed it.

There was no cure for his sickness but the sun. In this country, that was a rarity.

Valeria took to riding at the front of the caravan. Guards rode ahead of her, but they did not block what view there was. She could look her fill at trees, rocks and yet more trees. Dacius saw the virtue in what she was doing and rode just behind her. Iliya trailed after him, limp and green-faced. The Call was strong in all of them. They could not turn back now unless they were bound and dragged.

On the seventh day, or maybe it was the tenth, the clouds actually lifted. Valeria thought for a brief moment that she saw a patch of blue sky.

They were climbing yet another slope. For once it was not so steep that they needed to get off and walk. The pair of guards in front had gone up and over the top. Valeria’s horse picked up his pace slightly. Maybe it was the faintest hint of sky, or the minute brightening of the perpetual rain-colored light, but her heart felt lighter somehow. She was so full of the Call that she could hardly think.

As had happened too often before, the road reached the top only to plunge down at once into a deep valley. Just as Valeria paused, the clouds parted. She looked straight across to the country she had dreamed about since she was small.

It was all there. The long green valley with the river running through it. The walled fortress where the valley curved upward again toward the stony slopes. The sharp rise of the Mountain with its crown of snow. Forest surrounded the valley, but it was open and almost treeless, a gift of the gods to their dearest children.

At this distance she could see the walls of the school and the creneled bulk of towers, but little else. She needed no eyes to know what was there. The regular patches of brown and pale green around the feet of the walls were the fields and farmlands that fed the citadel. She could make out the clusters of farmhouses and the lines of hedges. The horse pastures were up behind the fortress, in high valleys protected by the Mountain itself.

The Call broke open inside her and became the whole of her. She had just enough sense left to see that Dacius had come up beside her and Iliya moved ahead of her. The pallor was gone from Iliya’s skin. He was as rapt as the rest of them. His eyes were narrowed and his face was shining as if he stared straight into the sun.

The guards had drawn aside. The way was open. They knew, thought Valeria. Those were the last words in her until she sat her hard-breathing horse in front of the gate.

She saw no guards anywhere near it. That did not mean it was unguarded. She looked up at the low round arch. The figures carved on it were so old that they were worn almost smooth. She could just make out a line of horses and riders, and a blurred shape that might be the Sun and Moon intertwined.

The gate was open, with darkness inside. It looked like a gaping mouth.

Her horse snorted softly and shook his mane. She started out of her stupor. Iliya snorted almost exactly like the horse. His mare trotted forward. Her hooves rang on the worn stones of the paving, echoing under the arch. She carried her rider inside.

Dacius’ mule was moving much more stolidly but as steadily as she ever had. They were leaving Valeria alone, with the caravan far behind, and nothing ahead but dreams and fear.

Valeria had come too far and with too much confidence to back off now. She took a deep breath and wiped her clammy palms on her breeches. The horse started forward without urging.

The wall was thick, but surely not as thick as this. She was in a tunnel with no end to it that she could see.

It was not totally dark. There were lamps, just bright enough for her to see the way. They seemed to float in the air.

On impulse she called one to her. As she had thought, it was a witch light. She asked it to burn brighter. It flared, blinding her. She damped it hastily. This place was full of magic. It turned the slightest whisper of a working into a shout.

The lamp hung just above her, burning steadily. In its light she saw the fitted stone of the tunnel’s walls and the interlocking tiles of its floor. She also saw that the tunnel bent and then divided. One way went up and one way went level.

She slid from the saddle and stood holding the black’s reins. There was no sign of the other horses and riders. The horse’s calm was not natural, but neither was this place.

She had known that there would be tests. What if this was meant just for her? What if she was barred from the school? She could convince men that she was one of them, simply by cutting her hair and wearing their clothes. Magic was not so easy to mislead.

The Call had come to her. She must be meant for the school. She could pass this test. It was a simple matter of choices.

“Don’t think,” her mother’s voice said. “Feel.”

She almost spun around to see if Morag had followed her to the Mountain. Then she caught herself. It was only memory.

It was also excellent advice. She squeezed her eyes shut and made herself breathe in a slow, steady rhythm. Each breath filled more of the world. It drove out thought and fear.

When she was empty of everything but air, she stepped forward. Her eyes were still shut. The horse walked quietly beside her.

She did not turn right or left. She went neither up nor down. She simply walked straight ahead.

Light dazzled her even through her eyelids. She heard voices and hoofbeats, and smelled horses and leather and fresh-baked bread.

She opened her eyes on a sunlit square. The gate was behind her. The clouds had parted, or maybe they had never dulled this place at all. She could feel the magic enclosed within these walls, distinct as the feel of sunlight on her skin.

Iliya was basking in the sun. Dacius looked around him with the same dazed expression she must have been wearing.

Tall grey buildings surrounded the square. People went back and forth inside it, busy with this errand or that. Not all were men. There were a few women in plain gowns like servants. One had a basket of laundry on her hip, and another stood by the fountain in the middle of the square, dipping water into an earthenware jar.

“That’s the Well of the World,” Iliya said. “It goes down to the source of all waters. It’s strong magic.”

There was so much magic in this place that Valeria could not tell if the story was true. She was too overwhelmed to argue with it.

Three men walked toward them. One was middle-aged, with the rolling walk and leathery look of the lifelong horseman. The other two were still a little soft around the edges, but they were cultivating the same weather-beaten style.

The older man greeted them in a broad country burr. “Good day to you, young gentlemen. My name is Hanno. I’m head groom in the candidates’ stable. We’ll take your horses, my boys and I, by your leave.”

None of them had the courage to object. Iliya let his beloved mare go with Hanno himself. Valeria said goodbye to the black. He had not been a friend, but he had been a good servant. She would miss him.

While the grooms took charge of the horses, another man approached them. He was dressed no better than the grooms, but his carriage was different. He walked, thought Valeria, the way Kerrec rode.

She met his glance and froze. He seemed a quiet, unassuming person, middle-aged and middle-sized, but the magic in him was so strong and so profoundly disciplined that she could not move or speak for the wonder of it.

He looked them over carefully, one by one. What he thought, Valeria could not have said. He did not seem terribly disappointed. After a while he said, “In the name of the white gods and the master of the school, I welcome you to the Mountain. You will call me Rider Andres.”

None of them had anything to say to that. He did not look as if he had expected them to. He turned his back on them and walked off at an angle across the square.

Evidently they were supposed to follow. They exchanged glances. Iliya shrugged. Dacius frowned. Valeria started walking in the man’s wake. After a pause, the others did the same.

Rider Andres led them through a narrow wooden door and up a flight of steps. The place to which he brought them was indistinguishable from a legionary barracks. It was a high, wide room with tall windows, open now to let in light and air, and a broad stone hearth at one end. Rows of bunks lined the walls. A hundred men could have slept there.