Полная версия

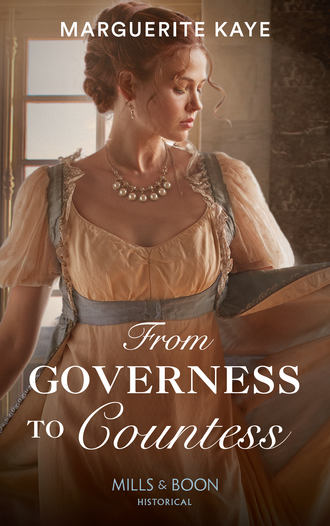

From Governess To Countess

A flotilla of small boats bobbed on the azure-blue waters. Stevedores called to each other in what she assumed was Russian, the words like no others she had ever heard, and Allison began to panic. The Procurer had assured her that French and English were the languages used by the aristocracy and their entourages with whom she would be mingling, but what if The Procurer was mistaken? What if this was an elaborate trap? What if The Procurer was in actual fact a procuress? What if she had been brought here under false pretences, to serve not as a...

‘Miss Galbraith?’ The man made a bow. Just in time, she noticed he wore a royal blue-and-gold livery, and spared herself the embarrassment of addressing him as her new employer.

‘I am come to escort you to the Derevenko Palace,’ the servant said, speaking just as The Procurer had promised, in perfect, if heavily accented, English. ‘I have a carriage waiting to take you there.’

Allison picked up her travelling herb chest by the brass handles, staggering under its weight, but waving the servant away when he made to take it from her. ‘No, I prefer to keep this with me, the contents are extremely precious. The rest of my baggage...’

‘All necessary arrangements have been made. The journey is a brief one. If you will follow me?’

She did as he bid, swaying a little as her feet adjusted to the solid ground beneath, coming to an abrupt, awed halt in front of the transport which awaited her. The carriage was duck-egg blue elaborately trimmed with gold, a coat of arms emblazoned on the doors. Another servant in the same livery sat on the boxed seat, holding the reins of two perfectly matched white horses. Inside, the plush squabs were the same royal-blue velvet as the groom’s livery, the floor covered in furs.

Peering through the large window as they trundled into motion, Allison observed that they turned immediately inland, following a road alongside a canal. The waters sparkled. The grand houses glittered. The sun shone. Everything looked so very perfect, so very beautiful, so very, very foreign and strange. A bridge spanned a small river not straight enough to be a canal, and the carriage followed the embankment for a short distance, passing ever more majestic mansions, before slowly drawing to a halt.

The groom opened the door and folded down the step. ‘Welcome to the Derevenko Palace, Miss Galbraith.’

It was indeed a palace. The edifice faced out over the river, on the other side of which was a vast expanse of open ground where what looked like a cathedral was under construction. Her first impression of the Derevenko Palace was that it reminded her of Somerset House on the Strand, neo-classical in style, three storeys high, with two wings stretching from the central portico, terminating in two smaller pedimented wings set at right angles, the shallow roof partially hidden by a carved balustrade. Above the central section, which was constructed almost like a square tower, a massive eagle-like stone bird was perched, gazing imperiously down its vicious curved beak at the shallow, sweeping staircase, and on Allison, who stood in trepidation on the bottom step. She shivered, thoroughly intimidated and battling the urge to turn tail and flee.

And where did she think she would go? Back on to the ship, back to the reclusive life she had been so delighted to leave behind?

Absolutely not! This was her second chance. She would not fail the woman who had presented her with it. More importantly, she would not fail herself. Not this time. Reluctantly handing her herb chest over to the groom, Allison straightened her shoulders, gathered up the folds of her travelling cloak and followed the manservant inside.

* * *

The interior made the façade of Derevenko Palace seem almost plain. A long strip of rich blue-and-gold carpet covered a floor of silver-and-pink stone laid in a herringbone pattern, which glittered under the glow of a magnificent chandelier. The carpet continued straight through a small entrance hall into another, bigger reception hall where two huge bronze lamps lit with a halo of candles flanked a sweep of enclosed stairs. Allison had a fleeting impression of immensely high and ornately corniced ceilings, before she was led up three flights of stairs to a half-landing, which then opened out into two stairways with elaborate bronze-gilt balustrades which in turn led to a massive atrium lit from above by light pouring through a central glass dome.

The servant paused in front of a set of double doors elaborately inlaid with ivory, mother of pearl and copper. He straightened his already perfectly straight jacket, and knocked softly before throwing the doors open. ‘Miss Galbraith, Your Illustrious Highness,’ he declared, waiting only until Allison edged her way into the room before exiting.

Your Illustrious Highness? Allison was expecting to meet a minor member of the aristocracy. She must surely be in the wrong room. Sinking into a low curtsy, she saw her own surprise reflected in the man’s demeanour. He had turned as the servant announced her, but took only one step towards her before coming to an abrupt halt. From her position, on legs still adjusting to being back on land, precariously close to toppling over, he looked ridiculously tall. Black leather boots, highly polished, stopped just above the knee, where a pair of dark-blue pantaloons clung to a pair of long, muscular legs. Which began to move towards her.

‘Surely there is some mistake?’ the imposing figure said. His voice had a low timbre, his English accent soft and pleasing to the ear.

‘I think there must be, your—your Illustrious Highness,’ Allison mumbled. She looked up, past the skirts of his coat, which was fastened with a row of polished silver buttons across an impressive span of chest. The coat was braided with scarlet. A pair of epaulettes adorned a pair of very broad shoulders. Not court dress, but a uniform. A military man.

‘Madam?’ The hand extended was tanned, and though the nails were clean and neatly trimmed, the skin was much scarred and calloused. ‘There really is no need to abase yourself as if I were royalty.’

His tone carried just a trace of amusement. He was not exactly an Adonis, there was nothing of the cupid in that mouth, which was too wide, the top lip too thin, the bottom too full. This man looked like a sculpture, with high Slavic cheekbones, a very determined chin, and an even more determined nose. Close-cropped dark-blond hair, darker brows. And his eyes. A deep Arctic blue, the blue of the Baltic Sea. Despite his extremely attractive exterior, there was something in those eyes that made Allison very certain she would not want to get on the wrong side of him. Whoever he was.

Belatedly, she realised she was still poised in her curtsy, and her knees were protesting. Rising shakily, refusing the extended hand, she tried to collect herself. ‘My name is Miss Allison Galbraith and I have travelled here from England at the request of Count Aleksei Derevenko to take up the appointment of governess.’

His brows shot up and he muttered something under his breath. Clearly flustered, he ran his hand through his hair, before shaking his head. ‘You are not what I was expecting. You do not look at all like a governess, and you most certainly don’t look like a herbalist.’

Allison, dressed in the most sombre of her consulting attire beneath her travelling cloak, bristled. ‘Ah, you were expecting a crone!’

‘A wizened one with a hairy chin,’ he said, with a smile that managed to be both apologetic and unrepentant.

‘I’m sorry to disappoint you on both counts,’ Allison replied, finding it surprisingly hard not to be charmed.

His smile broadened. ‘I find your appearance surprising, but far from disappointing. In my defence, I should tell you that I have very little experience on which to base my assumptions. I’ve never hired a governess until now and I’ve never before required a herbalist’s services. Forgive me, I am being remiss. I am Count Aleksei Derevenko,’ he said, making a brief bow. ‘How do you do, Miss Galbraith?’

Hers was not the only appearance to evoke surprise. This man did not look remotely like the father of three children in poor health and in need of English lessons. Portly, middle-aged, whiskered, red of face, bulbous of nose, is how she would have pictured such a man if she was in the habit of making sweeping assumptions. He would not have long, muscled legs that so perfectly filled those ridiculously tight breeches as to leave almost nothing to the imagination. He most certainly would not have the kind of mouth that made a woman’s thoughts turn to kissing. Or those eyes. Such a perfect, startling blue. Why couldn’t they have been watery or better still, bloodshot? And why, for heaven’s sake, was she thinking about him in such a manner in the first place?

‘I am not at all sure how I do, to be perfectly honest,’ Allison replied, inordinately flustered.

To her surprise, he laughed. ‘No more do I. It seems we have both confounded expectations. It is to be hoped that the person who brokered our temporary alliance knows her business. Let us sit and take some tea. We have a great deal to discuss.’

* * *

Aleksei ushered the Englishwoman to the far end of the reception room where the tea things had been set out on a low table, the samovar hissing steam from its perch on the woodchips. Solid silver, enamelled with white, blue and gold flowers, the delicate cups a matching pattern, the service was, like everything in this huge palace, designed to demonstrate the Derevenko dynasty’s wealth and lofty status. He had forgotten just how important appearances were, here in St Petersburg. No other European court—and on his travels, he’d been obliged to attend many—was as status conscious or such a hotbed of intrigue and ever-shifting alliances. No wonder that the woman now sitting opposite him on one of those ridiculously flimsy and uncomfortable little chairs had mistaken him for a prince, hearing that preposterous epithet. His Illustrious Highness, indeed.

She was clearly nervous, though she was trying not to show it, compulsively smoothing her gloves out on her lap. He still couldn’t quite believe that this was the woman The Procurer had promised him would be the answer to his urgent plea, that this was the woman whose arrival would signal the end of his agonising enforced spell of inactivity and allow him, finally, to begin his search to uncover the truth.

It struck him uncomfortably, as he looked at her, that the problem with this particular woman was not that she didn’t look like his preconceived notions of either a herbalist or a governess, but that she looked like his starved body’s idea of the perfect woman to take to his bed. Her hair was the colour of fire. No, that was too obvious. It was the cover of leaves on the turn, of glossy chestnuts, of the sky as the sun sank. She was not conventionally beautiful, there was nothing of the demure English rose, so universally admired, about her. She was something wilder, untamed. Her skin seemed to glow with vitality, her figure was not willowy but voluptuous. She had a mouth that made a man think of all the places he would like those lips to touch. And then there were her eyes—what colour were they? Brown? Gold? Both? Was it her heavy lids that made him think of tumbled sheets and morning sunshine dappling her delightfully naked rump?

Aleksei cursed under his breath. Since Napoleon’s escape from Elba, followed by Waterloo, and the formal mourning period he had just completed here in St Petersburg, he had been deprived of all female company, but this was most definitely not the time and place to be having such thoughts. Allison Galbraith was not here to satisfy his inconveniently awakening desires. He should be contemplating her suitability for the task, not her body. Though he could not deny that her body was one that he’d very much like to contemplate.

Would anyone believe her a credible replacement for Anna Orlova the previous, long-serving governess? A paragon, if the servants were to be believed, utterly reliable, and much loved by the children. Whether or not she returned that affection, Aleksei had no idea, since Anna Orlova had abandoned her charges and fled the Derevenko Palace long before he had had a chance to set eyes upon her.

He picked up the teapot which sat on top of the samovar, only to drop it with a muted curse as the heated silver handle scalded his palm. Covering the handle with the embroidered linen cloth designed for that very purpose, he saw that Miss Galbraith was staring at the urn with a puzzled look. ‘You are not familiar with the ceremonial Russian tea ritual?’ Happy to buy himself time to regather his thoughts, when she shook her head Aleksei concentrated on the performance. ‘This is the zavarka, the black tea, which we brew for at least fifteen minutes, unlike you English, who barely allow the leaves to kiss the hot water before you pour.’ Kiss? An unfortunate choice of verb. Touch, then? No, that was even worse!

He concentrated on pouring a small amount of zavarka into her cup, a larger, stronger amount into his own. The samovar hissed, reminding him that he had not completed the tea-making ceremony. ‘This is kipyatok,’ he said, ‘which is simply another word for boiling water. Would you like a slice of lemon, some sugar?’

‘Is that permitted?’

‘It is not traditional, but I have both available if you wish. Our tea is something of an acquired taste.’

‘I will take it as it is meant to be served. When in Russia, as they say.’ Miss Galbraith picked up her cup and took a tentative sip.

She did not quite spit it out, but her screwed-up little nose and her watering eyes told their own tale. Biting back a smile, Aleksei held out the sugar bowl.

Using the tongs, she dropped three cubes of sugar into the tiny cup. ‘I hope you don’t think I’m being impertinent, but may I enquire why your wife is not here to greet me? I assume it is from her that I will take my instructions?’

‘Her absence is easily explained. I’m not, and never have been married.’

‘Oh.’ Miss Galbraith coloured. ‘I see,’ she said, looking like someone who did not see at all.

‘The children are not mine,’ Aleksei explained, ‘they are my brother’s.’

She frowned. ‘Then may I ask why you are—why I am not having this discussion with your brother and his wife?’

‘Because they are both dead.’ Drinking his own, thick black tea, a soldier’s brew, from the ducal cup in one gulp, Aleksei registered the widening of her eyes, and realised belatedly how stark this statement sounded. ‘Michael and Elizaveta died in May this year, within a few days of each other.’

Which attempt at tempering the shock made things worse. Miss Galbraith blanched. ‘How awful. I am so terribly sorry.’

‘Yes.’ Aleksei curbed his impatience. It was awful, but he’d had almost four months to accustom himself to it. ‘However, the formal mourning period is now over.’ Did that sound callous? ‘My brother and I were not particularly close.’ Even worse? Best to just get on with the matter in hand. ‘It is the consequences of his death which concern me, Miss Galbraith, and that is the reason you are here.’

‘Consequences?’

Though he was relieved to be back on track, Aleksei found himself in a quandary. It was already clear that the distractingly luscious Miss Galbraith had been only partially briefed by The Procurer woman. Her reputation for complete discretion was well founded, thank the stars, which meant he had the luxury of not having to launch into a full exposition of what he euphemistically referred to as consequences to a complete stranger just off the boat. But precisely how much to tell her?

Aleksei decided to proceed with caution. ‘Michael bequeathed me the guardianship of his offspring in his will—I have no idea why, for he did not consult me on the matter. I am, as my brother knew perfectly well, as unsuitable a guardian for his children as it’s possible to imagine, and have no intentions of continuing in the post once I can secure a more suitable candidate. At which point, Miss Galbraith, your duties will come to an end.’

‘Oh. Then my appointment as governess—you envisage it being of very short duration?’

‘I sincerely hope so. What I mean,’ Aleksei continued, noting her slightly startled expression, ‘is that I hope my appointment will be of short duration. Four months ago, when I received word of Michael’s death, I was preparing to do battle with Napoleon’s army. Having done my duty by my country and my men at Waterloo, I was obliged to return immediately to St Petersburg to take up my new, unasked-for duties. As you have no doubt surmised, I did not take kindly to having been bounced from battle to babysitting without a moment to catch my breath.’

‘Though Napoleon’s defeat has made it unlikely that you’ll have to fight any battles any time soon, has it not? Now that Europe is at peace you can surely be more easily spared to devote yourself to your new duties.’

Aleksei blinked at this unexpected riposte. Miss Galbraith, it seemed, had recovered her composure, and inadvertently unsettled his by pointing out a truth which had not occurred to him and which he had absolutely no desire to contemplate. ‘I am a soldier, have always been a soldier, and have no wish to be anything other than a soldier. Peace has certainly granted me the freedom to fulfil the obligations my brother forced upon me, but that does not mean I wish to spend the rest of the foreseeable future acting in loco parentis.’

‘I see.’

She did not. She thought him callous. Aleksei bristled. He did not need to justify himself to her. ‘The children will be far better off in the care of a guardian who understands the workings of the court, and how best to raise them to take their place in it.’

‘To be perfectly frank, I know nothing of royal courts and their etiquettes. I hope you were not expecting...’

‘You need not concern yourself about that. Apart from anything else, the children are too young, though Catiche...’

‘Catiche? I’m sorry, but I know only that there are two girls and a boy, I have no idea of their names and ages.’

‘That, I am pleased to tell you, I can easily remedy,’ Aleksei said. ‘Catiche—that is Catherine—is thirteen. Elena is ten. Nikki, my brother’s heir, is four. You will make their acquaintance the day after tomorrow. When I had word that your ship had docked this morning, I packed them off to stay with friends for a couple of nights, to allow you time to settle into your new surroundings.’

‘Thank you, that was thoughtful. May I ask how the little ones have coped with the loss of their parents? They must have been devastated.’

‘They seem perfectly well to me,’ Aleksei replied, frowning, ‘though my time is so taken up with my brother’s man of business that I see very little of them which, assuming they are being raised as my brother and I were, is no change to the status quo. They have a nanny, a peasant woman as is the tradition, who has cared for them since they were in the nursery. If they were devastated by anything, it’s more likely to have been the loss of Madame Orlova, their governess of some years’ standing.’

‘Loss? Good gracious, don’t tell me that she too perished? Was there some sort outbreak in the palace, a plague of some sort?’

‘No, no—you misunderstand. Madame Orlova left her post somewhat abruptly the day before my brother died.’

Miss Galbraith said something under her breath in a language he did not recognise. ‘Those poor little mites. What appalling timing. What prompted her to leave?’

‘I have absolutely no idea and nor have I been able to discover a single person in the army of servants here who does. I’ve tried to locate her, but if she’s in St Petersburg then she’s very well hidden, and I’ve been unable to widen my search since I am loath to leave the children for any sustained period without proper supervision. Now you are here, I intend to make tracking her down a priority.’

‘You intend to reunite her with her charges?’

Aleksei hesitated, reluctant to blatantly lie. ‘I must establish why she left in such haste before deciding anything.’ That much was true enough.

‘I don’t know why it didn’t occur to me before, but while I was assured that both English and French are widely spoken in polite society here, I didn’t ask specifically about the children. Obviously I speak no Russian.’

‘There will be no need for you to do so. The children will have picked up Russian from their nanny as we all did, but they have been taking French and English lessons from Madame Orlova from a very young age, so you need not fear you will be unable to make yourself understood.’ Indeed, Aleksei thought, Catiche’s fluency was such as to render any English tutoring virtually redundant. No matter, by the time Miss Galbraith discovered this for herself, he’d have explained the true reason for her presence here.

Which he most decidedly did not wish to do just yet. It was time to conclude this most extraordinary conversation. Miss Galbraith had already demonstrated that she had a sharp mind. It would not be long before she asked him why the devil he had not found someone closer to home to perform what must seem to be a fairly straightforward task, and he wasn’t ready to answer that question just yet. Not until he’d made sure that St Petersburg society, that hotbed of scandal and intrigue, took Miss Galbraith, English governess, at face value and did not question her presence in the palace.

Aleksei had intended to introduce her at a soirée or a small party. There was, in the euphoric aftermath of victory at Waterloo, no shortage of social events to choose from. As it so happened, this very night a much grander affair was taking place. It would be a baptism of fire, but he was confident that she would emerge unscathed. It wasn’t only the guarantees he’d received from The Procurer—though they certainly helped. No, it was Miss Allison Galbraith herself. She was confident—once she had got the better of her quite understandable early nervousness. She was without question clever. And feisty, a woman whose fiery temperament matched her red hair. He reckoned she would fight her corner, so he’d better make sure they were in the same corner. And as for her other qualities? Irrelevant. Absolutely, completely, ravishingly irrelevant.

But also, without question, an absolutely completely, delightful bonus. A most unwelcome distraction from the task in hand undoubtedly, but from a personal point of view a very welcome one. For the first time since he had read that life-changing letter from Michael’s man of business, he felt his spirits lift. ‘If you have finished your tea, I will have a servant show you to your quarters. You have...’ Aleksei consulted his watch. ‘...three hours to prepare.’

She stared at him blankly. ‘To prepare for what?’

‘Your introduction to society,’ he informed her blithely. ‘I did not expect The Procurer to send me a sultry redhead, but your appearance could actually work in our favour. By tomorrow morning, all of St Petersburg will know that there is a new English governess at the Derevenko Palace.’

Chapter Two

Four hours later, Allison found herself standing in the foyer of the Winter Palace, the official home of the Russian royal family. Her hand was resting lightly on the arm of a disturbingly attractive man she had met for the first time today. And she was wearing a dead woman’s ball gown. Not, the maid Natalya had hastened to assure her, that the Duchess Elizaveta had ever worn the garment, it was one of many gowns the Duchess had owned but never worn. All the same, were it not for the fact that she possessed only one evening gown, and that not at all suitable for a ball at a royal palace, Allison would have refused to have worn it. It felt both inappropriate and slightly macabre.

She had had no option, however, and though she selected the very plainest of those offered to her, the luxurious garment was outrageously glamorous and utterly unlike anything she would ever have chosen to purchase. White silk with an overdress of creamy net, the evening dress was embellished with tiny gold-thread flowers, a seed pearl at the centre of each. There was a demi-train, the puff sleeves and the surprisingly modest décolleté were trimmed with scalloped lace, and a narrow sash of gold ribbon was tied just under her bust, in the style made popular by the Empress Josephine. The layers of satin-and-lace petticoats made a faint rustling noise when she moved, like fronds swaying in the breeze. For long moments, staring at her reflection in the mirror earlier, Allison had been quite transported by the idea of gliding round a ballroom in such a very beautiful garment. Beautiful but absurdly complicated, mind you. She’d had to fight the urge to ask Natalya for donning instructions.